2 Fractures of the Humerus

Overview

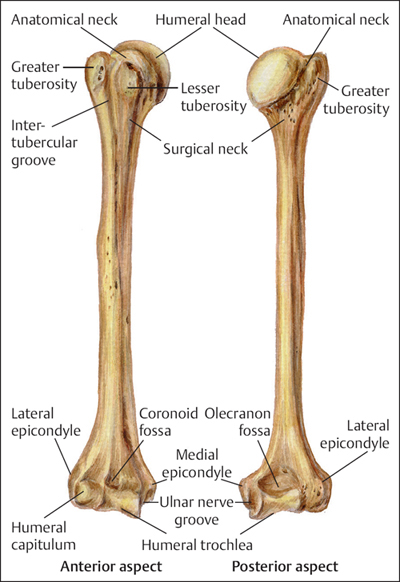

Anatomic Features

Anatomic Features

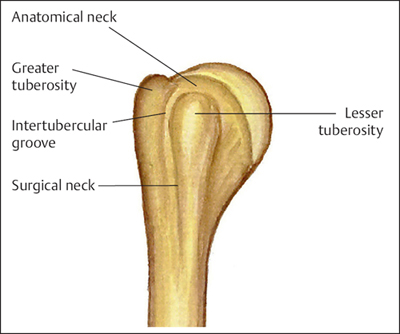

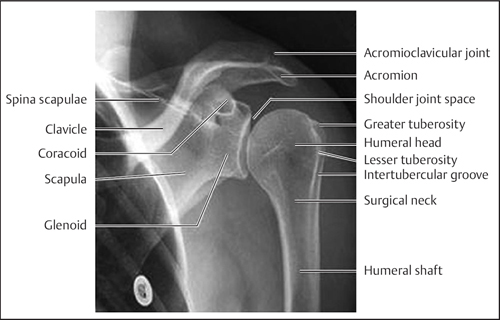

The humerus (Plate 2.1) is the longest and largest bone of the arm, and is divided into a body and two extremities. The proximal humerus is part of the radiographic anatomy of the shoulder. The humeral head is nearly hemispheric in shape, and articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. The greater tubercle, situated lateral to the head, has three areas of muscle insertion: the supraspinatus superiorly, the infraspinatus in the middle, and the teres minor inferiorly. Situated in front of the head is the lesser tubercle, into which the tendon of the subscapularis inserts. The tubercles are separated from each other by a deep groove named the intertubercular groove, which contains the long tendon of the biceps brachii. The articular surface of the head is called the anatomic neck, and provides attachment for the articular capsule of the shoulder joint. The surgical neck is the narrowing below the tubercles and is frequently the site of fracture of the proximal humerus. The body runs from the tubercles, is almost cylindric in its upper half, and gradually flattens and gains a prismatic shape. The radial nerve winds around the posterior aspect of the humerus, running laterally in the radial sulcus toward the forearm. The lower extremities are flattened, broad, and thin proximally, while they are thicker at the two tuberculated eminences (lateral and medial epicondyles). The trochlea and the capitulum of the humerus articulate with the semilunar notch of the ulna and the margin of the radial head, respectively, to form the humeroulnar articulation and the humeroradial articulation.

Plate 2.1

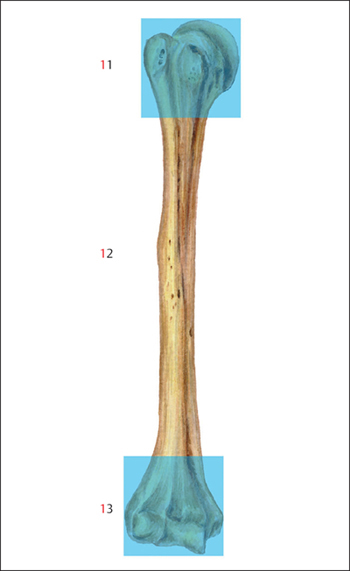

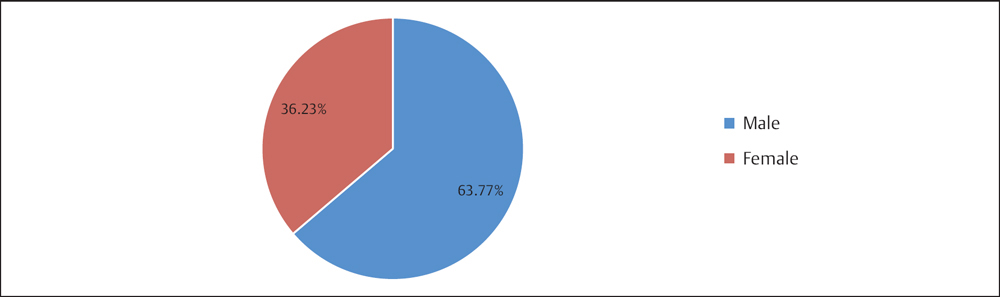

AO Classification and Coding System for Humeral Fractures

AO Classification and Coding System for Humeral Fractures

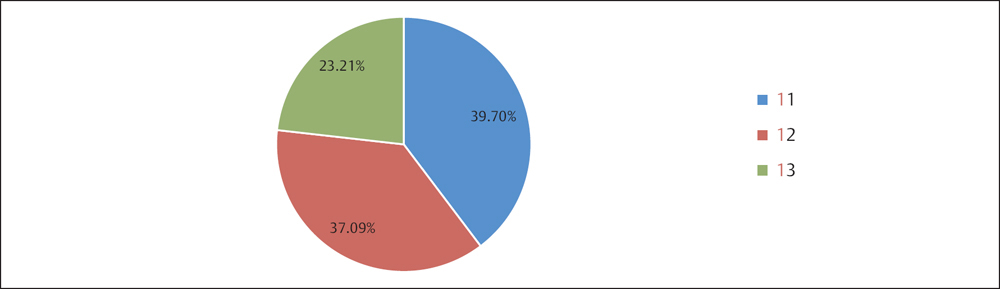

The humerus is assigned the number “1” based on the AO system and is further divided into three zones: 11: proximal fracture; 12: shaft fracture; and 13: distal fracture (Plates 2.2 and 2.3).

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Humeral Fractures

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Humeral Fractures

A total of 6039 patients with 6076 humeral fractures were treated at our trauma center over a 5-year period from 2003 to 2007. All cases were reviewed and statistically studied; the fractures accounted for 10.02% of all patients with fractures and 9.31% of all types of fractures. Among 6039 patients, 2819 were children with 2827 fractures, and 3220 were adults with 3249 fractures.

The epidemiologic features of humeral fractures are as follows:

• more males than females

• more left sides involved than right sides

• the highest-risk age group is 0–10 years

• in adults, fractures occur most frequently in the proximal humerus; in children they occur most frequently in the distal humerus.

Plate 2.2

Plate 2.3

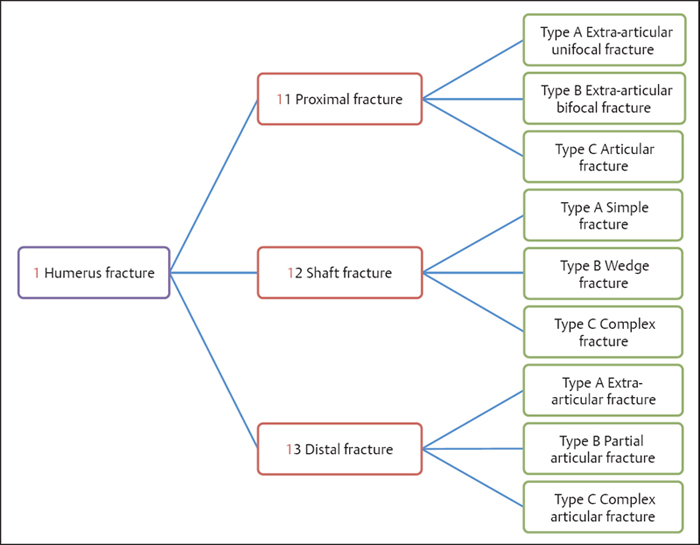

Humeral Fractures by Sex

Humeral Fractures by Sex

Table 2.1 Sex distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures

| Sex | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Male | 3851 | 63.77 |

| Female | 2188 | 36.23 |

| Total | 6039 | 100.00 |

Fig. 2.1 Sex distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures.

Humeral Fractures by Injured Side

Humeral Fractures by Injured Side

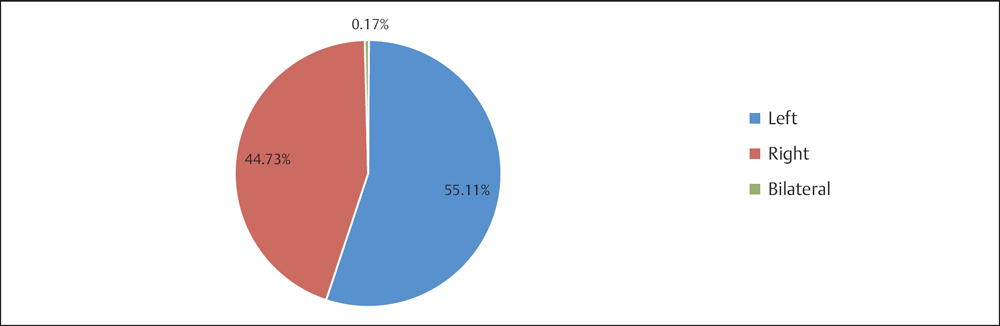

Table 2.2 Injury side distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures

| Injured side | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Left | 3328 | 55.11 |

| Right | 2701 | 44.73 |

| Bilateral | 10 | 0.17 |

| Total | 6039 | 100.00 |

Fig. 2.2 Injury side distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures.

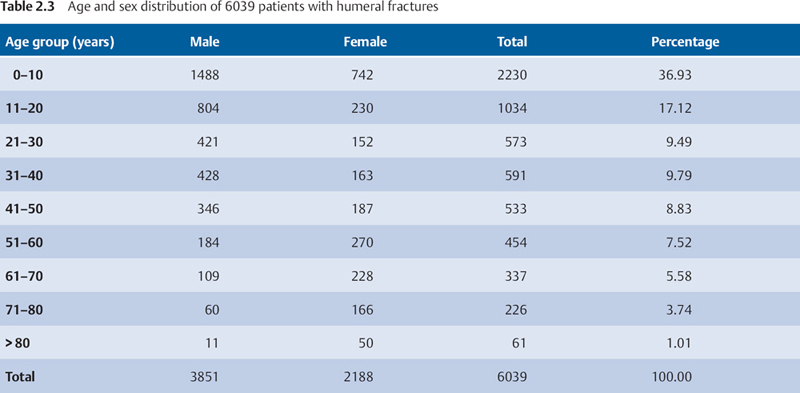

Humeral Fractures by Age Group and Sex

Humeral Fractures by Age Group and Sex

Fig. 2.3 a, b

a Age distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures.

b Age and sex distribution of 6039 patients with humeral fractures.

Humeral Fractures by Location

The Distribution of Humeral Fractures by Segments in Adults Based on AO Classification

The Distribution of Humeral Fractures by Segments in Adults Based on AO Classification

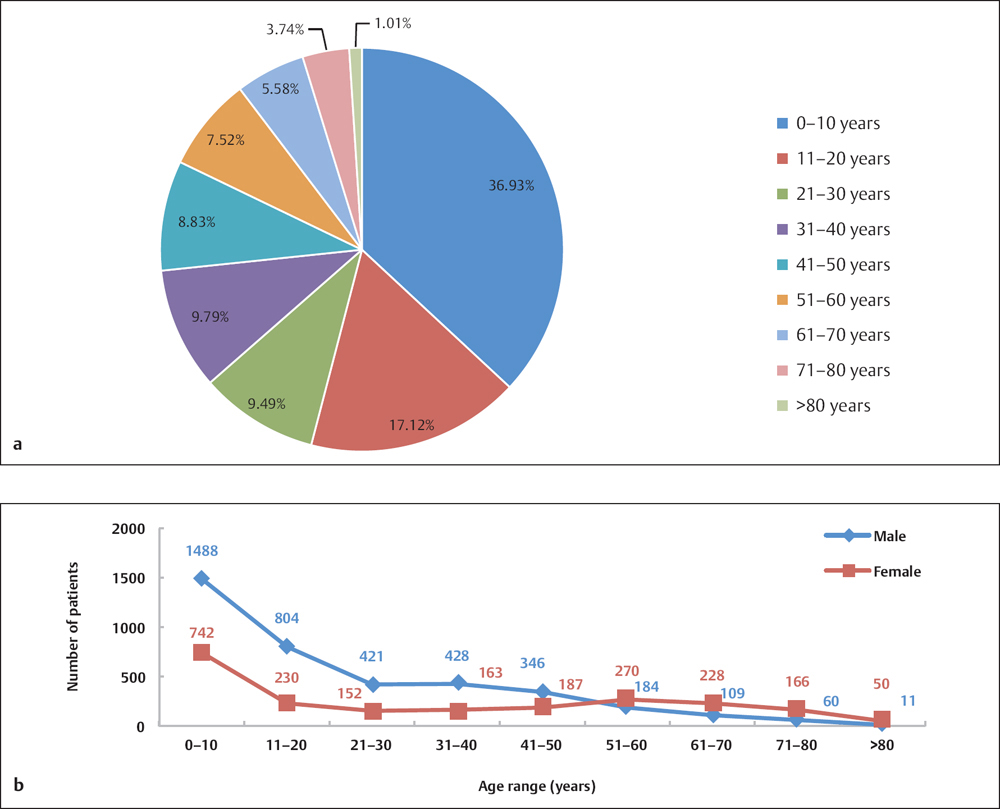

Table 2.4 Segment distribution of 3249 humeral fractures in adults based on AO classification

| Segment | Number of fractures | Percentage |

| 11 | 1290 | 39.70 |

| 12 | 1205 | 37.09 |

| 13 | 754 | 23.21 |

| Total | 3249 | 100.00 |

Fig. 2.4 Segment distribution of 3249 humeral fractures in adults based on AO classification.

The Distribution of Humeral Fractures by Segments in Children

The Distribution of Humeral Fractures by Segments in Children

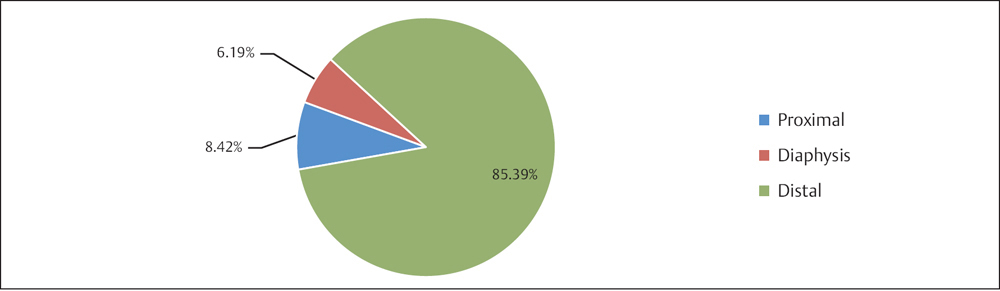

Table 2.5 Segment distribution of 2827 humeral fractures in children

| Segment | Number of fractures | Percentage |

| Proximal | 238 | 8.42 |

| Diaphysis | 175 | 6.19 |

| Distal | 2414 | 85.39 |

| Total | 2827 | 100.00 |

Fig. 2.5 Segment distribution of 2827 humeral fractures in children.

Proximal Humeral Fractures (Segment 11)

Anatomic Features

Anatomic Features

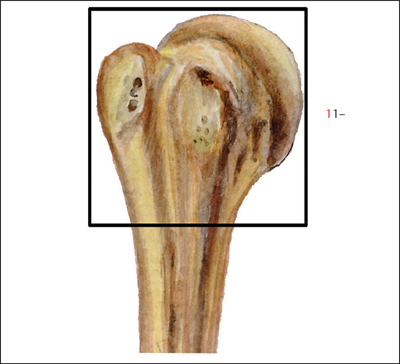

The proximal part of the humerus consists of the head, two eminences, the greater and lesser tubercles, and the surgical neck (Plate 2.4). The humeral head has a hemispheric shape, which has a superior, medial, and posterior aspect. The narrow groove separating the head from the tubercles is the anatomic neck, where fractures rarely occur but there is a high incidence of avascular necrosis due to disruption of the blood supply to the main head fragment. The narrowing below the tubercles, called the surgical neck, is the junction of the two tubercles with the cylindric shaft. It is frequently fractured because the cortex at this part of the bone abruptly becomes quite thin. The greater tubercle is situated laterally and posteriorly to the proximal humerus, and provides insertion points for the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor. The ridge descending down the shaft from the root of the greater tubercle is called the crest of the greater tubercle, into which the pectoralis major muscle inserts. The lesser tubercle, situated anteriorly, represents the center of the humeral head and provides an insertion point for the subscapularis. The crest descending from the lesser tubercle has attachments to the latissimus dorsi and the teretiscapularis. The intertubercular groove lodges the long tendon of the biceps brachii (Plates 2.5 and 2.6).

Plate 2.4

Plate 2.5

Plate 2.6

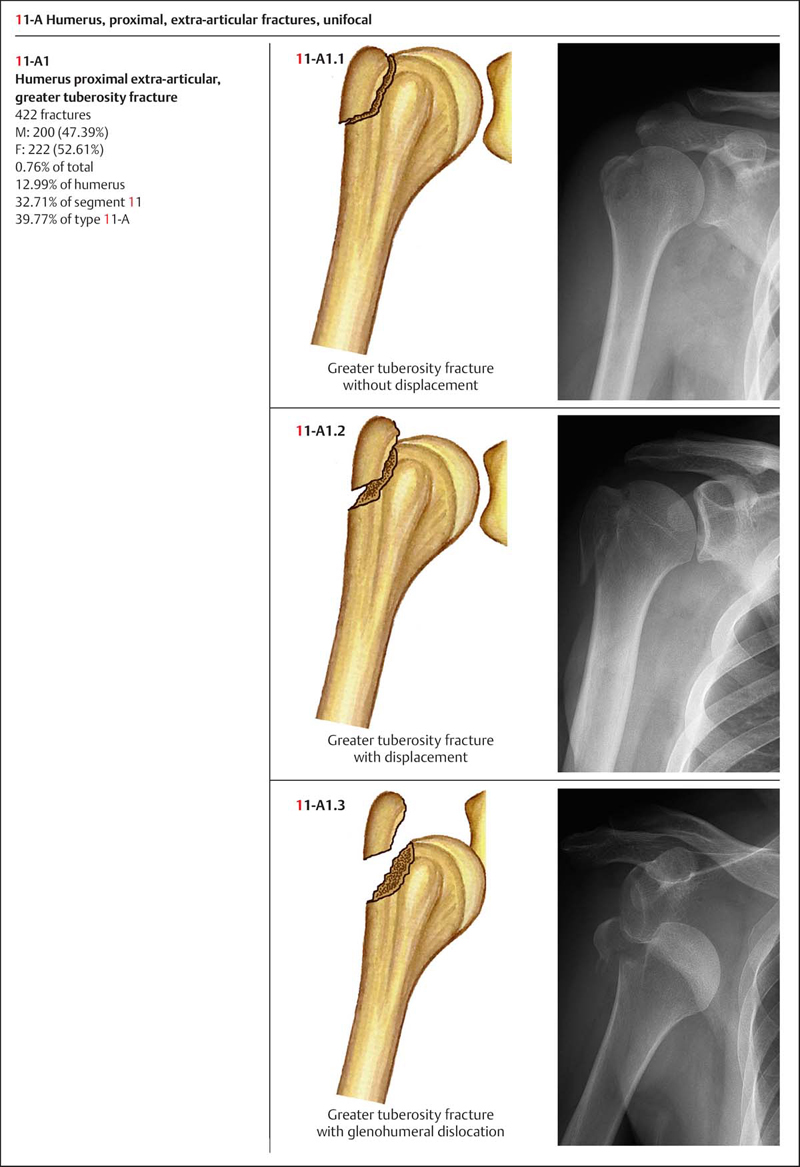

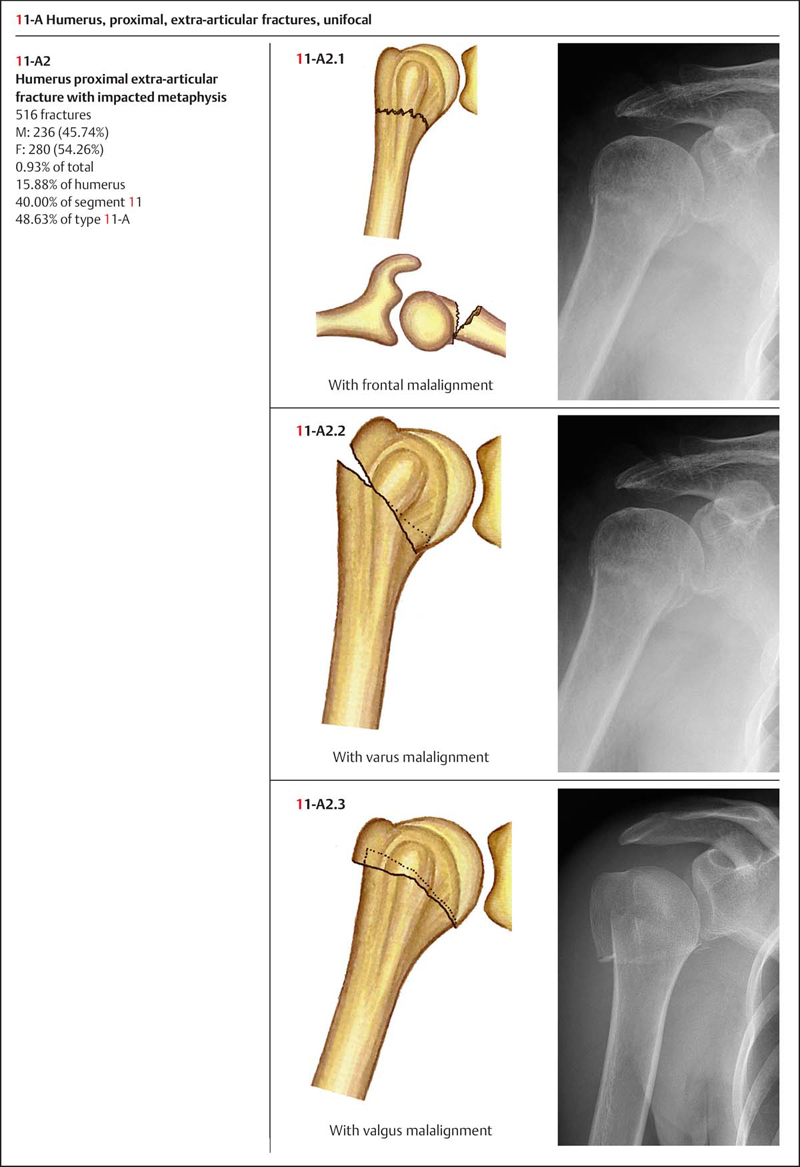

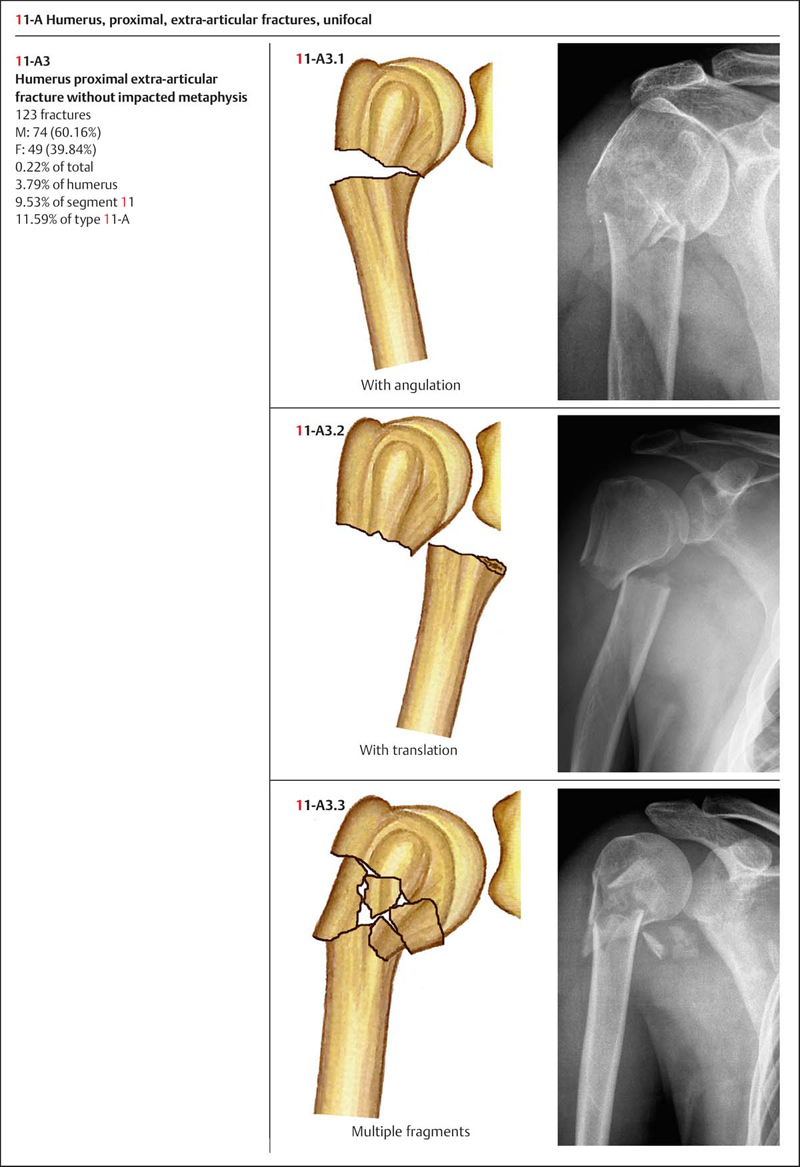

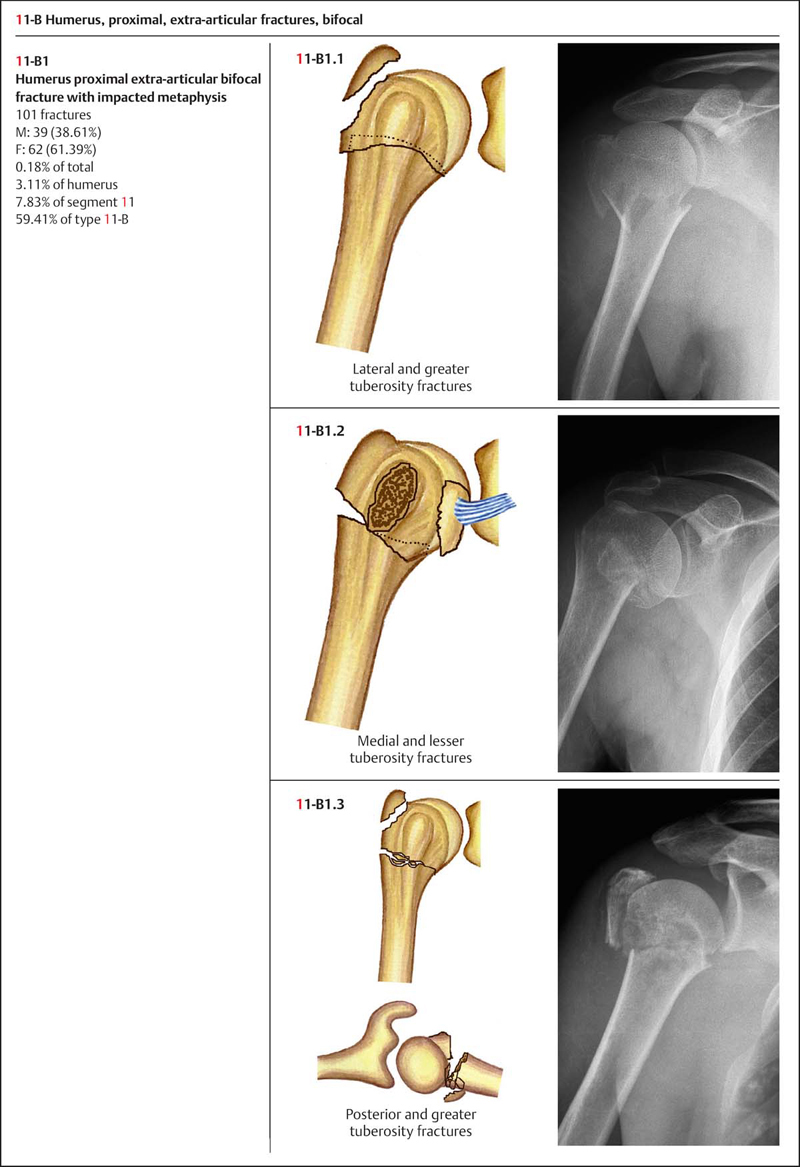

AO Classification of Proximal Humeral Fractures

AO Classification of Proximal Humeral Fractures

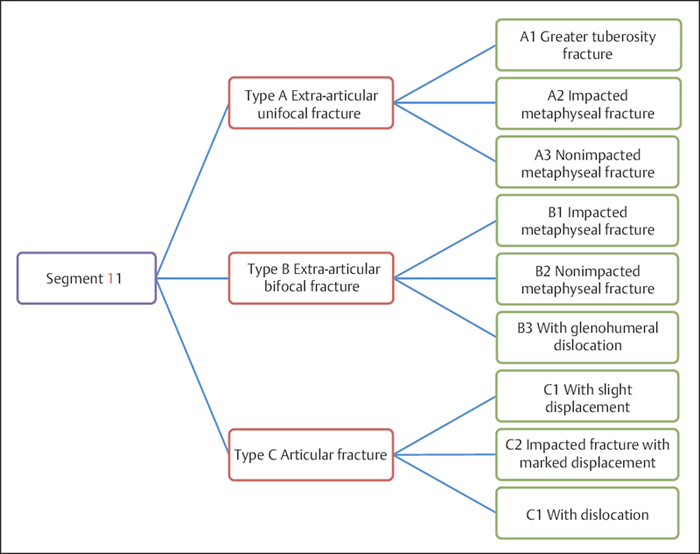

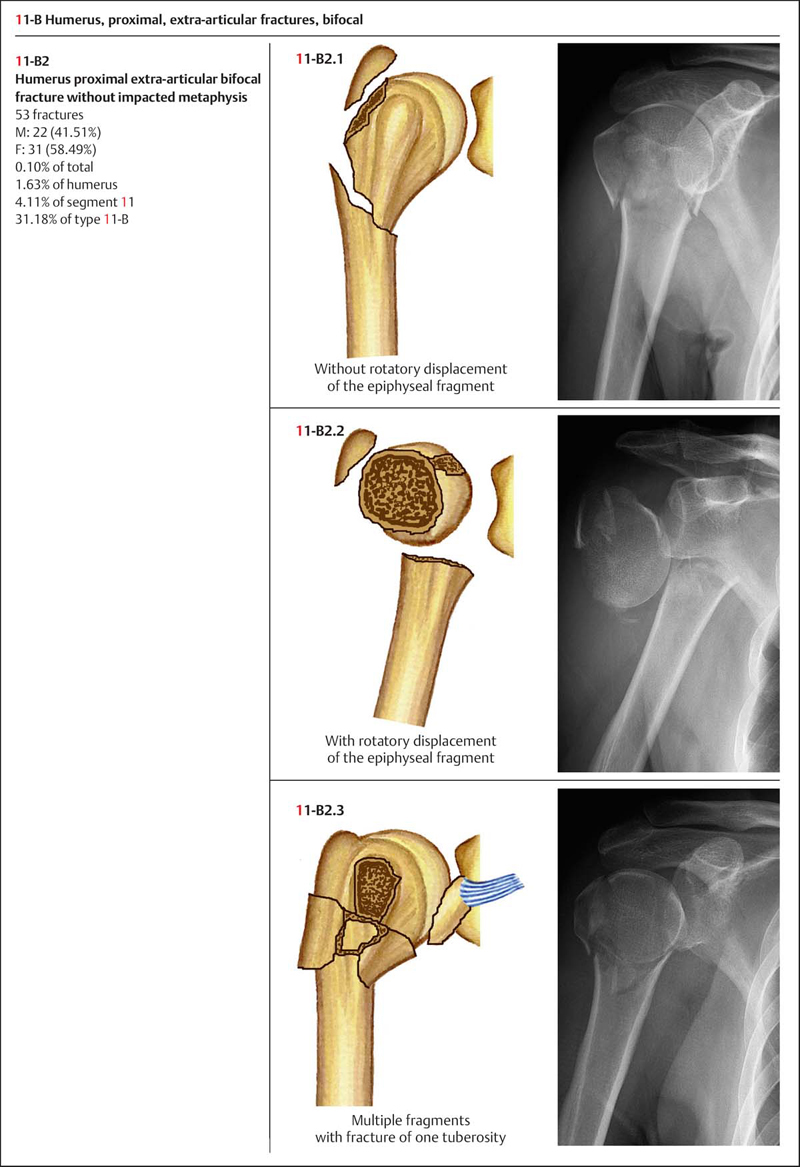

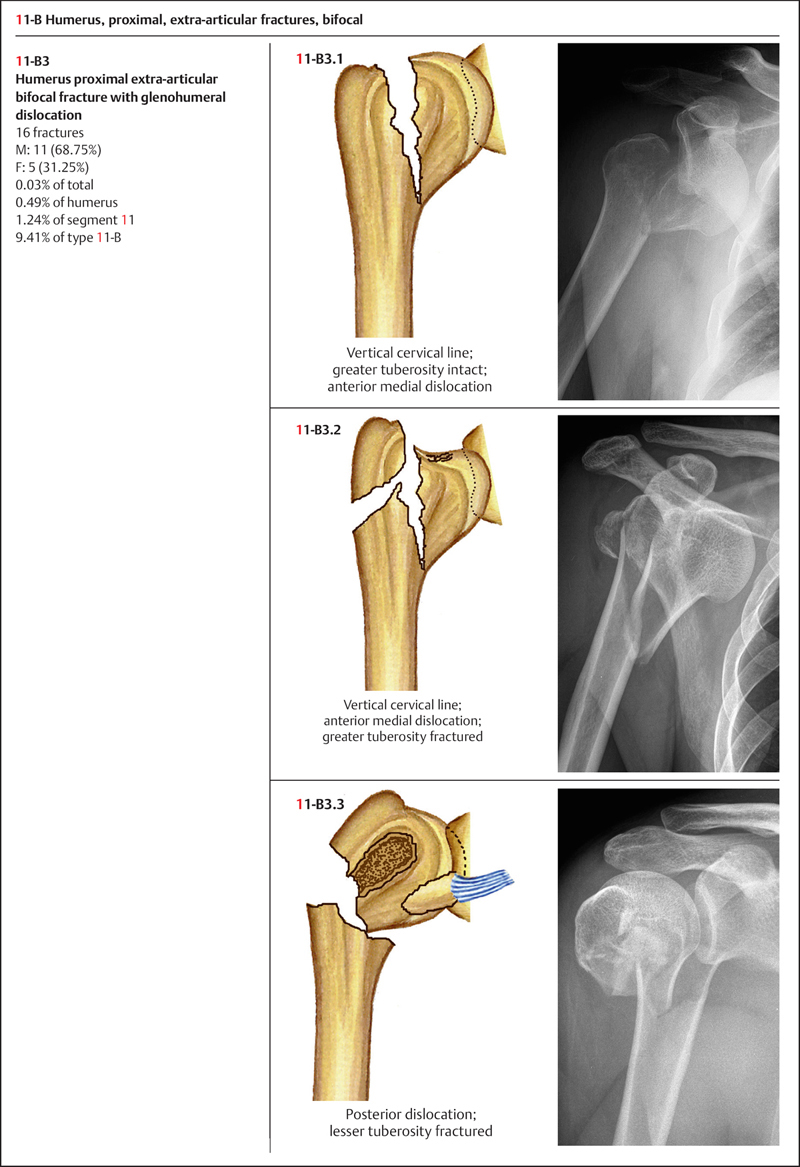

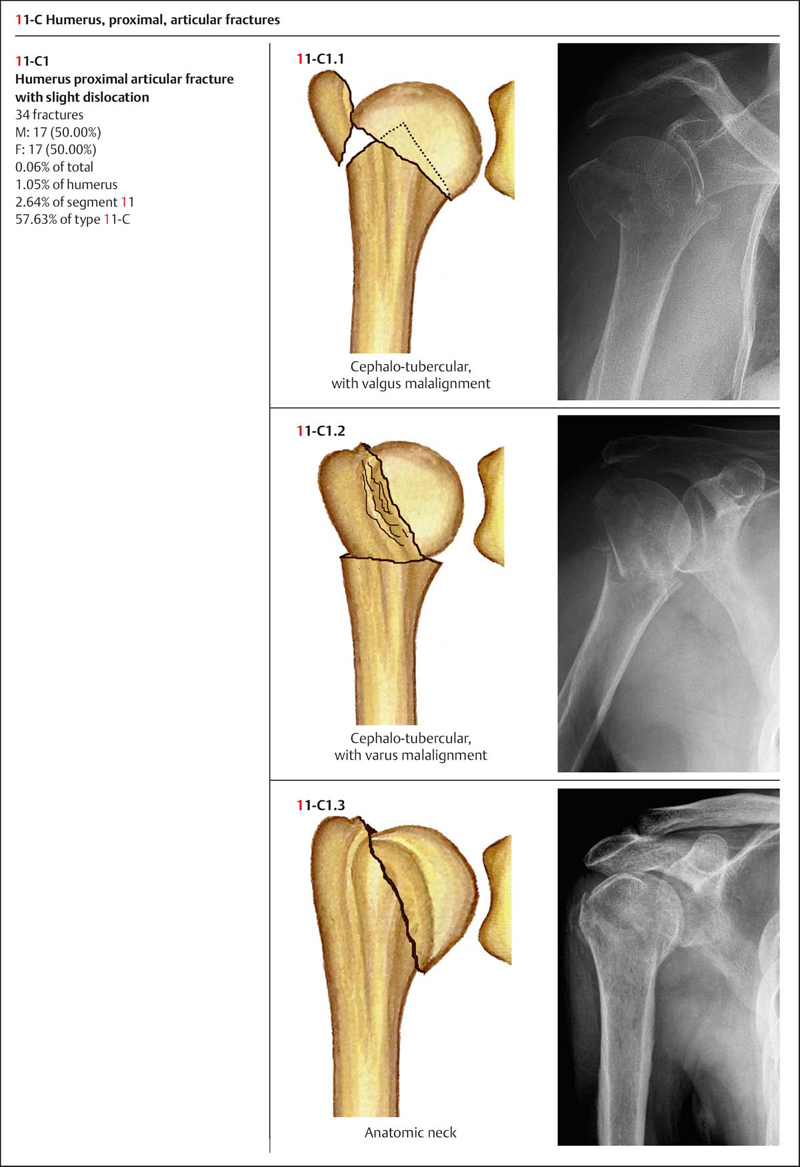

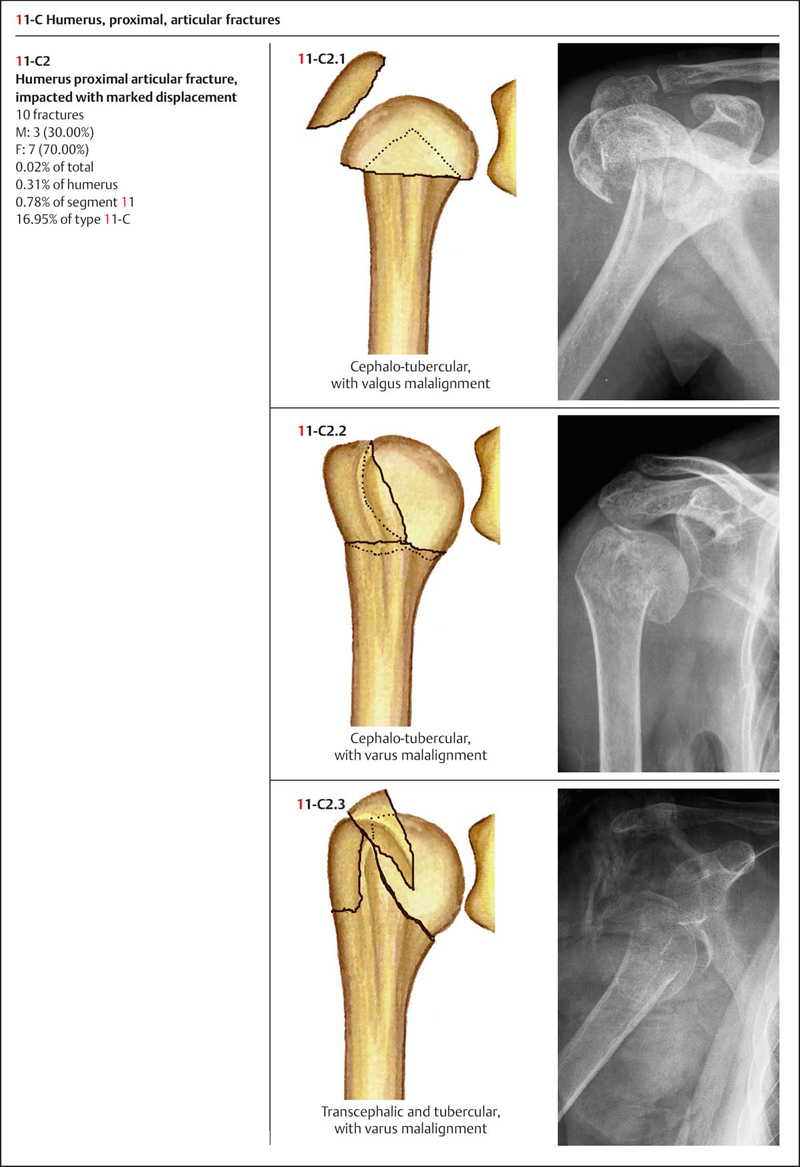

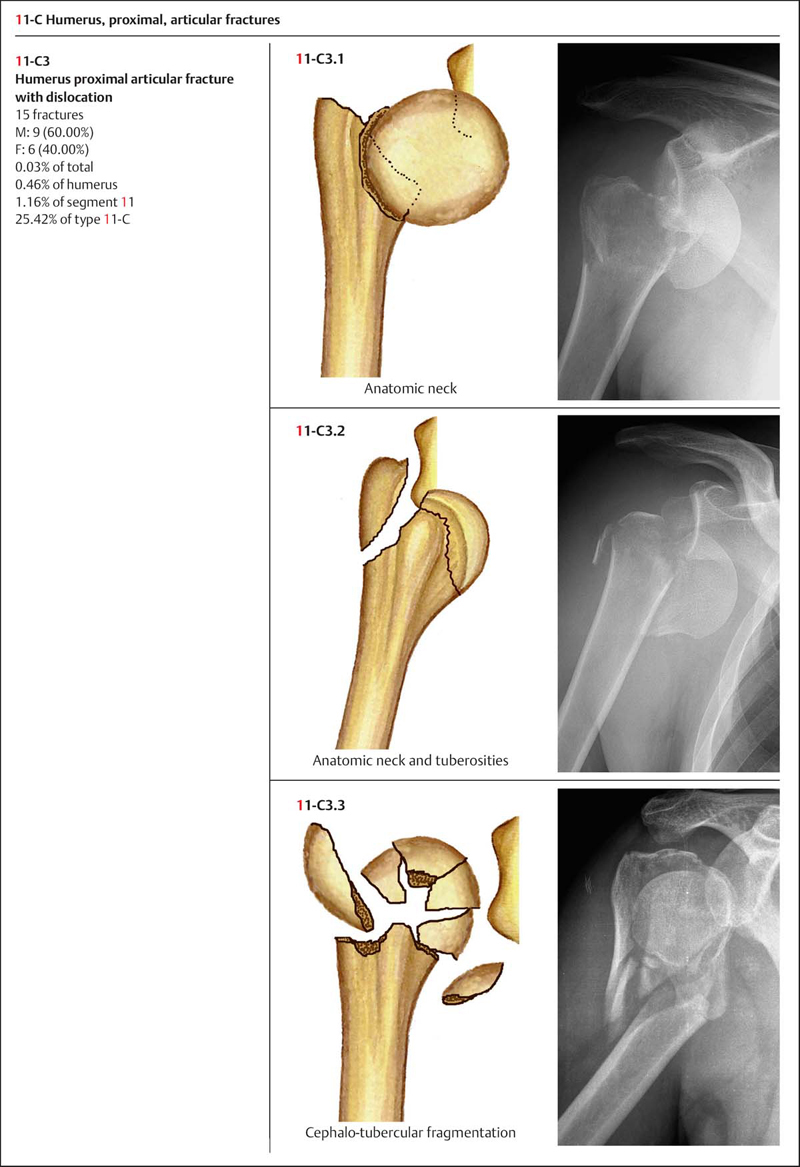

Based on AO classification, the proximal end of the humerus is delineated by a square with its lateral side equal to the maximum width of the epiphysis. The AO coding of a proximal humerus fracture is “11,” and is further divided into three categories based on the severity of injury: types A, B, and C (Plate 2.7).

Plate 2.7

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Proximal Humeral Fractures (Segment 11)

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Proximal Humeral Fractures (Segment 11)

A total of 1290 adult proximal humeral fractures (segment 11) were treated at our trauma center over a 5-year period from 2003 to 2007. Each case was reviewed and statistically studied; the fractures accounted for 39.70% of adult humeral fractures. The epidemiologic features are as follows:

• more males than females

• the high-risk age group includes ages 41–60 years, specifically ages 41–50 years for males and ages 51–60 years for females

• the high-incidence type is 11-A, and is the same for both males and females

• the high-incidence group is 11-A2, and is the same for both males and females.

Fractures of Segment 11 by Sex

Fractures of Segment 11 by Sex

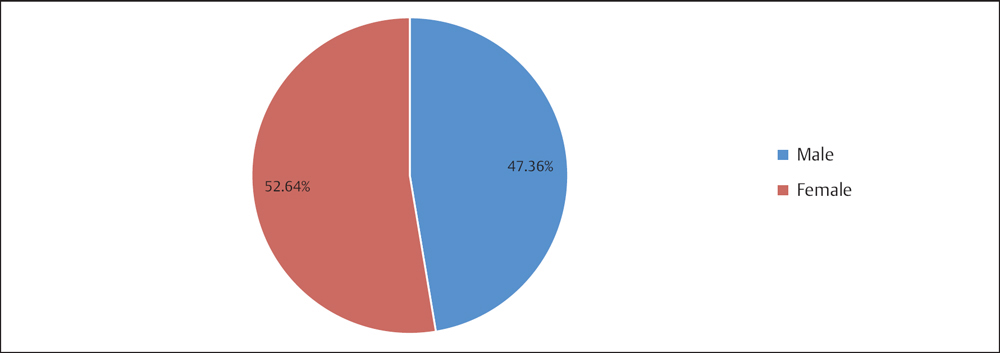

Table 2.6 Sex distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11

| Sex | Number of fractures | Percentage |

| Male | 611 | 47.36 |

| Female | 679 | 52.64 |

| Total | 1290 | 100.00 |

Fig. 2.6 Sex distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

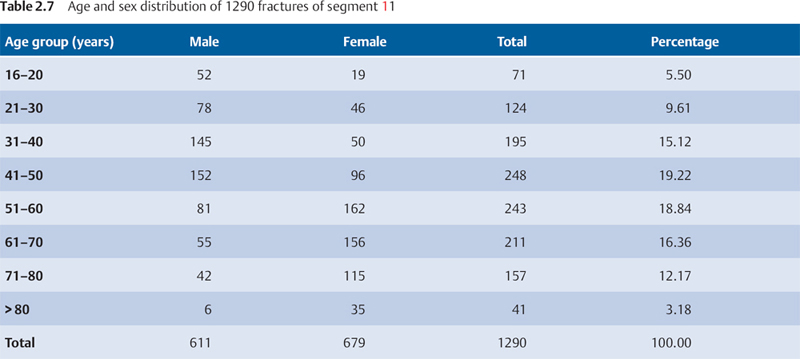

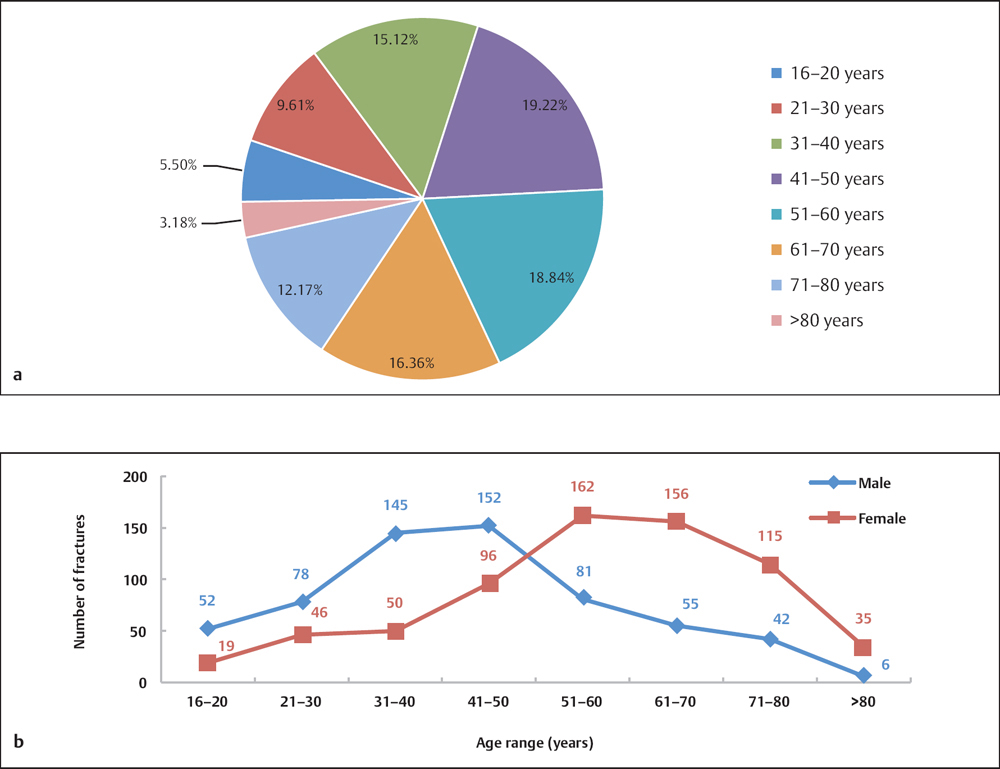

Fractures of Segment 11 by Age Group

Fractures of Segment 11 by Age Group

Fig. 2.7 a, b

a Age distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

b Age and sex distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

Fractures of Segment 11 by Fracture Type

Fractures of Segment 11 by Fracture Type

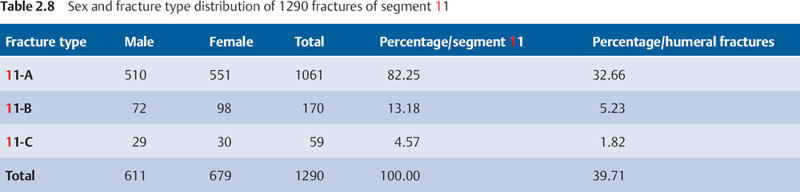

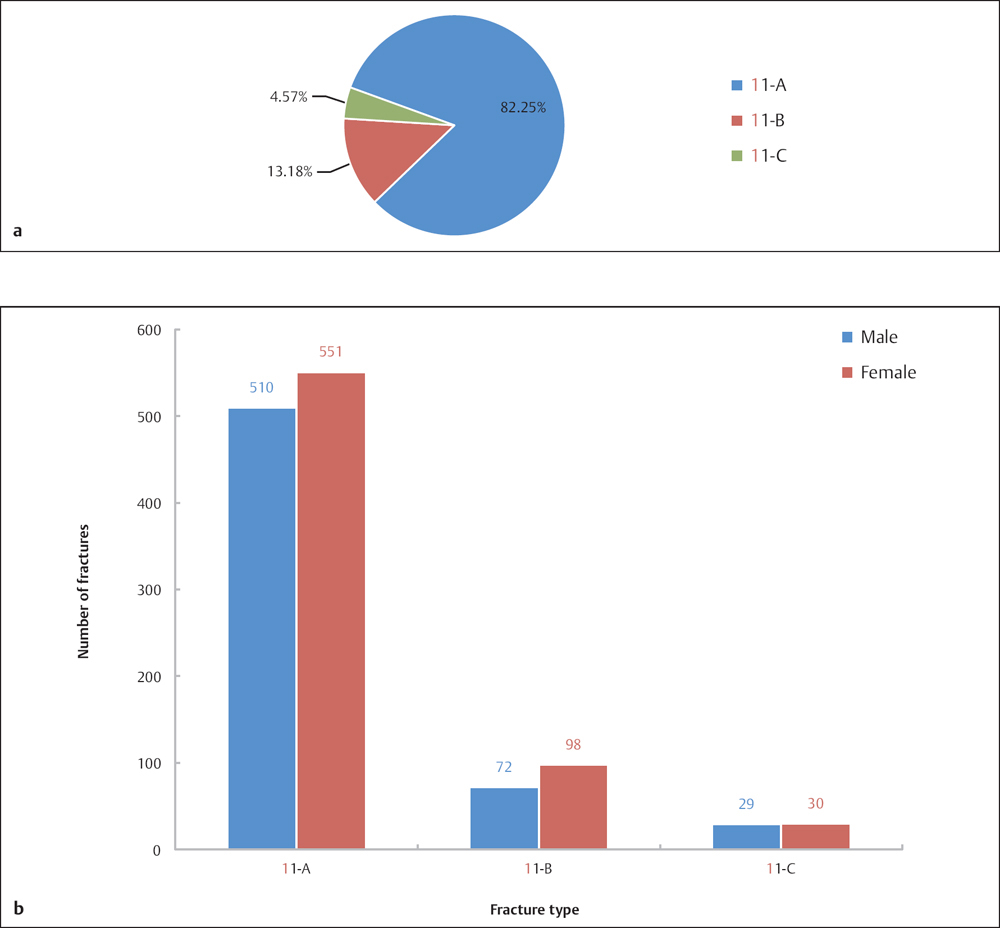

Fig. 2.8 a, b

a Fracture type distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

b Sex and fracture type distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

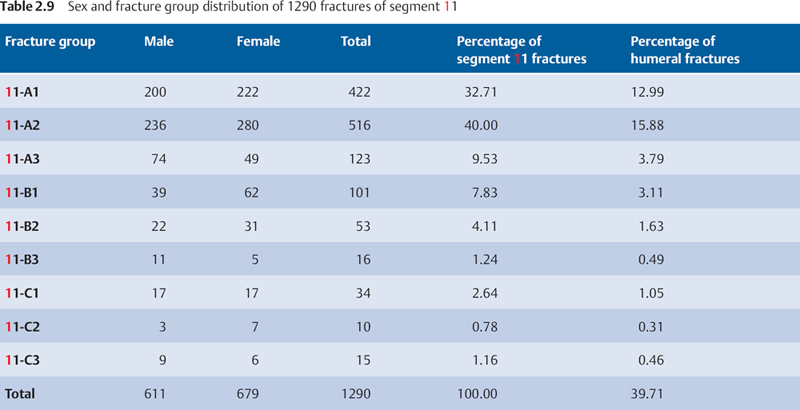

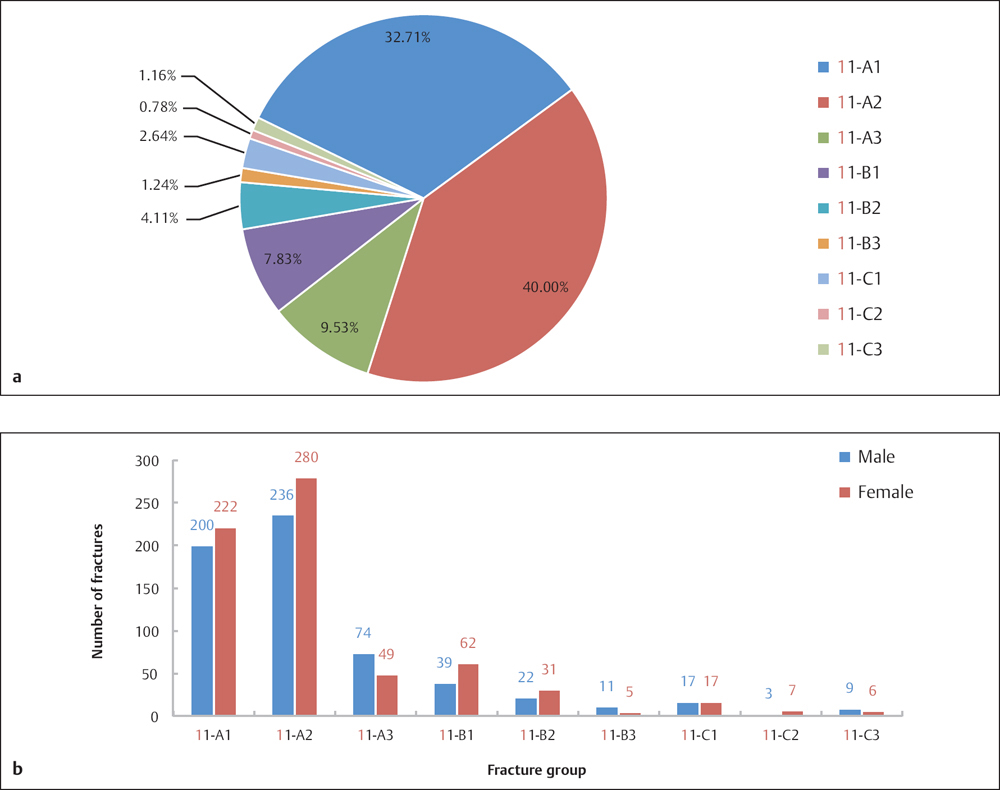

Fig. 2.9 a, b

a Fracture group distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

b Sex and fracture group distribution of 1290 fractures of segment 11.

Injury Mechanism

Injury Mechanism

Proximal humeral fractures are often caused by indirect force. In elderly patients, fractures are usually associated with osteoporosis, and can be caused by low or moderate force, such as that seen in falls from a standing position. For example, during a fall with an upper extremity in the outstretched position, when one’s hand touches the ground the lateral shoulder is subjected to an upward directed force, and this results in a proximal humeral fracture. Young patients often receive fractures from high-energy and direct-force impact to the proximal humerus.

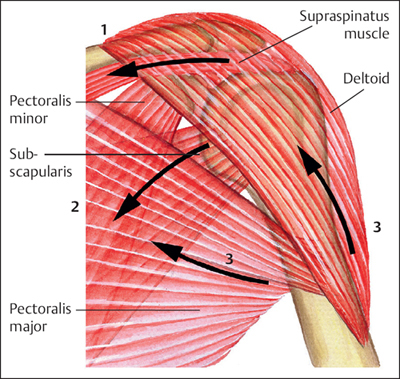

When fractures occur, the greater tuberosity fragment is usually pulled superoposteriorly by the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor. In contradistinction, the lesser tuberosity fragment usually moves medially due to traction from the subscapularis. When surgical neck fractures occur, the proximal fragment is usually shortened and displaced due to traction from the deltoid, and the distal fragment is pulled medially by the pectoralis major.

The black arrows on Plate 2.8 indicate the directions of displacement of four anatomic structures (1: greater tuberosity; 2: lesser tuberosity; 3: humeral shaft) after fracture, under traction of the rotator cuff muscles, deltoid, and pectoralis major.

Plate 2.8

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Pain, swelling, and restricted motion are usually present when fracture of the proximal humerus occurs. If the fracture involves the articulation site, with minimal or no displacement, then the swelling and deformity may not be visible, due to protection from thick soft tissue around the shoulder. Tenderness of the shoulder and bone crepitus indicate a fracture. If a fracture fragment becomes displaced, a palpable cavity in the glenohumeral joint will be noted. It is essential to determine the presence of any associated neurovascular injury. The axillary artery and axillary nerve are most commonly injured in proximal humerus fractures.

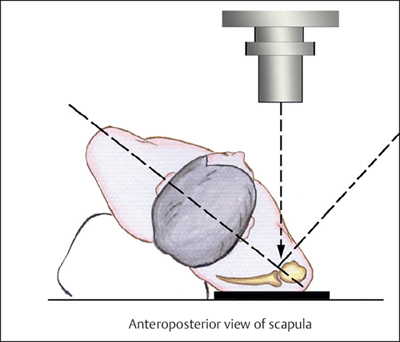

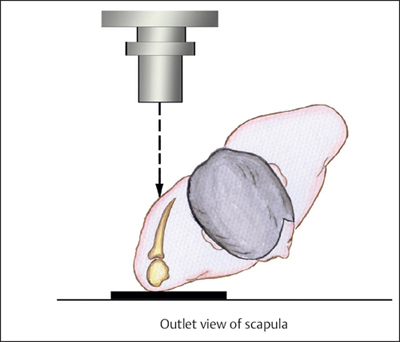

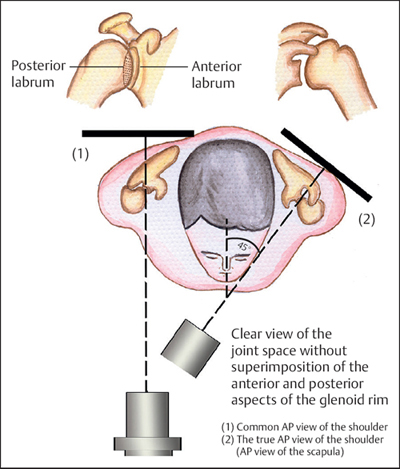

The trauma series of radiographic evaluation for suspected proximal humerus fractures consists of anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views in the scapular plane and an axillary view.

• When obtaining an AP view (Plate 2.9), the patient stands in a position with the shoulder to be examined in contact with the examining table. The scapula should lie parallel to the cassette, and the X-ray beam must be tilted 40° to the plane of the thorax. Good visualization of the subacromial space should be obtained with no overlap of the humeral head and glenoid cavity, resulting in the anterior and posterior rim of the glenoid fossa being superimposed.

• To obtain an outlet view (Plate 2.10), the patient stands in an anterior oblique position, with the anterior aspect of the examined shoulder in contact with the cassette, and the X-ray beam parallel to the scapular spine with the body tilted 40°.

Plate 2.9

Plate 2.10

Since the plane of the scapula is 30–40° anterior to the coronal plane of the body, the glenohumeral joint inclines anteriorly, and the glenoid fossa directly faces the humeral head posteriorly. The common AP view and transthoracic lateral projection of the shoulder both provide a lateral view of the shoulder joint, neither of which are true reflections of the displacement, angulation, or dislocation of the proximal humeral fracture (Plate 2.11).

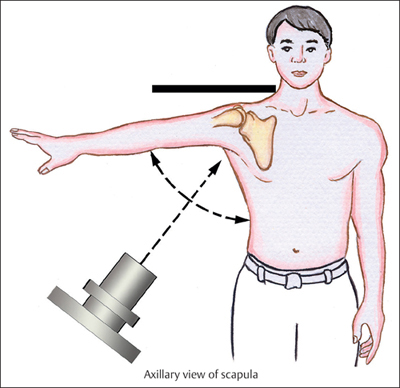

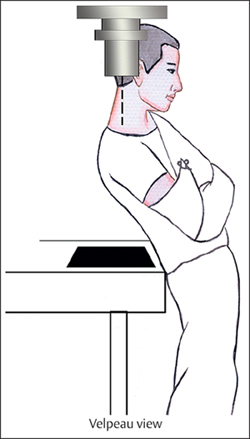

• To obtain an axillary view (Plate 2.12), the patient is placed in a supine position with his or her arm abducted 70–90°. The cassette is placed on the superior aspect of the shoulder and the beam can be centered on the axilla. In recently occurring fractures, since abduction of the shoulder is markedly restricted due to the pain, a modified axillary view, known as a Velpeau view (Plate 2.13), is used. In this view, the patient is in a standing position and is tilted backward ~ 30° over the cassette on the table. The X-ray beam is then projected vertically from above the shoulder onto the cassette. This view is limited by unavoidable overlapping of structures; thus a supine projection is the recommended choice of imaging in practice.

If the radiographic evaluation is equivocal or if there is soft-tissue damage, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be a good imaging choice to provide more accurate information for early diagnosis and proper treatment. Doppler ultrasound or angiography can be of great assistance if the proximal humeral fracture is associated with dislocation or with vascular injury.

Plate 2.11

Treatment

Treatment

Plate 2.12

Plate 2.13

Proximal humeral fracture with minimal or no displacement may be treated nonoperatively with satisfactory results. However, for patients older than 50 years, minimally invasive surgery for internal fixation is recommended to avoid the occurrence of traumatic periarthritis of the shoulder joint. An unstable fracture, or one with marked displacement, requires surgical stabilization. Surgical management in patients with osteoporosis or severely comminuted fractures cannot achieve satisfactory results by reduction and stabilization; therefore, prosthetic replacement for the joint should be applied for such patients.

Humerus Shaft Fractures (Segment 12)

Anatomic Features

Anatomic Features

The shaft of the humerus (Plate 2.14) extends from the upper border of the pectoralis major insertion site to the supracondylar ridge distally. The proximal aspect of the humeral shaft is cylindric on cross-section; distally, its anterior–posterior diameter narrows. The medial and lateral intermuscular septa divide the arm into anterior and posterior compartments. The anterior compartment contains the biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and brachialis muscles. The brachial artery and vein, and median, musculocutaneous, and ulnar nerves course along the medial border of the biceps. The triceps brachii muscle and radial nerve are contained in the posterior compartment. The radial nerve winds around the radial sulcus in between the medial and lateral heads of the triceps brachii, perforating the lateral intermuscular septum at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the humeral shaft and entering the anterior aspect of the arm, which makes it an easy target when fractures and dislocations occur at this location.

Plate 2.14

AO Classification of Humeral Shaft Fractures

AO Classification of Humeral Shaft Fractures

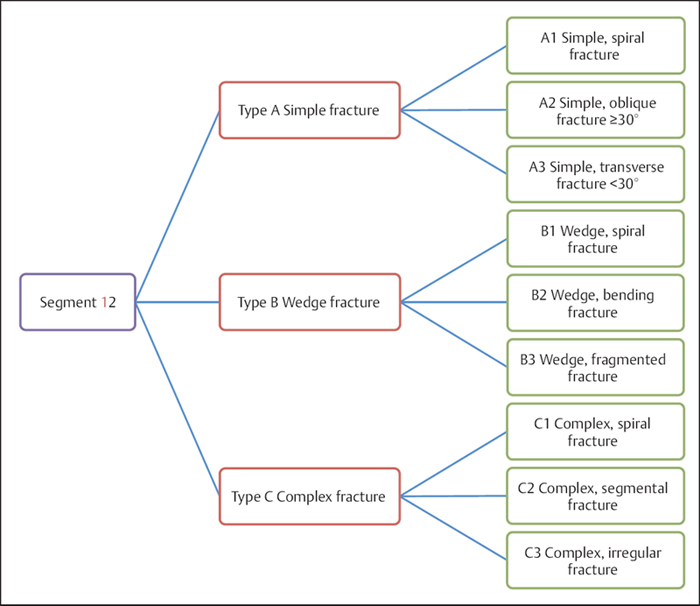

The humeral shaft segment is coded as number “12” based on the AO classification, and is further divided into three main types depending on fracture morphology: types A, B, and C (Plate 2.15).

Plate 2.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree