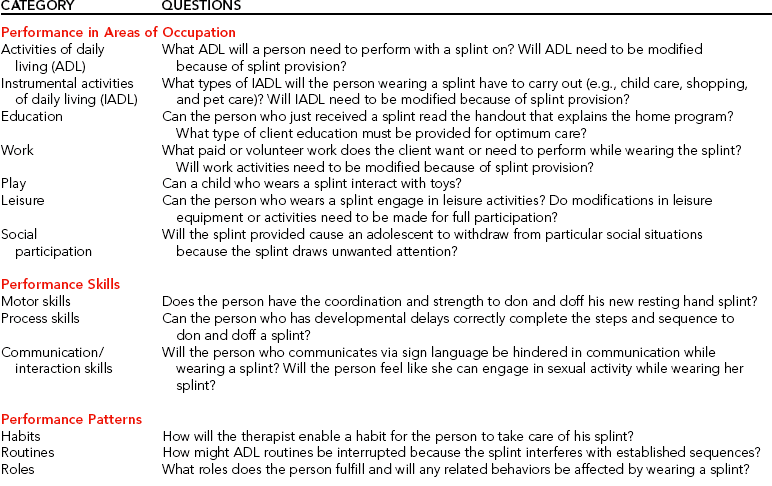

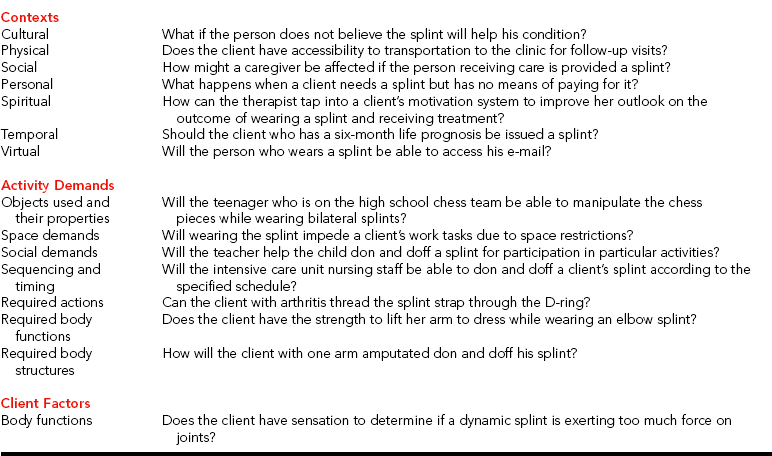

CHAPTER 1 1 Define the terms splint and orthosis. 2 Identify the health professionals who may provide splinting services. 3 Appreciate the historical development of splinting as a therapeutic intervention. 4 Apply the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) to optimize evaluation and treatment for a client. 5 Describe how frame-of-reference approaches are applied to splinting. 6 Familiarize yourself with splint nomenclature of past and present. 7 List the purposes of immobilization (static) splints. 8 List the purposes of mobilization (dynamic) splints. 9 Describe the six splint designs. 10 Define evidence-based practice. 11 Describe the steps involved in evidence-based practice. 12 Cite the hierarchy of evidence for critical appraisals of research. Determining splint design and fabricating hand splints are extremely important aspects in providing optimal care for persons with upper extremity injuries and functional deficits. Splint fabrication is a combination of science and art. Therapists must apply knowledge of occupation, pathology, physiology, kinesiology, anatomy, psychology, reimbursement systems, and biomechanics to best design splints for persons. In addition, therapists must consider and appreciate the aesthetic value of splints. Beginning splintmakers should be aware that each person is different, requiring a customized approach to splinting. The use of occupation-based and evidence-based approaches to splinting guides a therapist to consider a person’s valued occupations. As a result, those occupations are used as both a means (e.g., as a medium for therapy) and an end to outcomes (e.g., therapeutic goals) [Gray 1998]. Reports of primitive splints date back to ancient Egypt [Fess 2002]. Decades ago, blacksmiths and carpenters constructed the first splints. Materials used to make the splints were limited to cloth, wood, leather, and metal [War Department 1944]. Hand splinting became an important aspect of physical rehabilitation during World War II. Survival rates of injured troops dramatically increased because of medical, pharmacologic (e.g., the use of penicillin), and technological advances. During this period, occupational and physical therapists collaborated with orthotic technicians and physicians to provide splints to clients: “Sterling Bunnell, MD, was designated to organize and to oversee hand services at nine army hospitals in the United States” [Rossi 1987, p. 53]. In the mid 1940s, under the guidance of Dr. Bunnell many splints were made and sold commercially. During the 1950s, many children and adults needed splints to assist them in carrying out activities of daily living secondary to poliomyelitis [Rossi 1987]. During this time, orthotists made splints from high-temperature plastics. With the advent of low-temperature thermoplastics in the 1960s, hand splinting became a common practice in clinics. Today, some therapists and clinics specialize in hand therapy. Hand therapy evolved from a group of therapists in the 1970s who were interested in researching and rehabilitating clients with hand injuries [Daus 1998]. In 1977, this group of therapy specialists established the American Society for Hand Therapy (ASHT). In 1991, the first certification examination in hand therapy was given. Those therapists who pass the certification examination are credentialed as certified hand therapists (CHTs). Specialized organizations (e.g., American Society for Surgery of the Hand and ASHT) influence the practice, research, and education of upper extremity splinting [Fess et al. 2005]. For example, the ASHT Splint Classification System offered a uniform nomenclature in the area of splinting [Bailey et al. 1992]. The OTPF outlines the occupational therapy process of evaluation and intervention and highlights the emphasis on the use of occupation [AOTA 2002]. Performance areas of occupation as specified in the framework include the following: activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. Performance areas of occupation place demands on a person’s performance skills (i.e., motor skills, process skills, and communication/interaction skills). Therapists must consider the influence of performance patterns on occupation. Such patterns include habits, routines, and roles. Contexts affect occupational participation. Contexts include cultural, physical, social, personal, spiritual, temporal, and virtual dimensions. The engagement in an occupation involves activity demands placed on the individual. Activity demands include objects used and their properties, space demands, social demands, sequencing and timing, and required actions, body functions, and body structures. Client factors relate to a person’s body functions and body structures.Table 1-1 provides examples of how the framework assists one in thinking about splint provision to a client. The practice of occupational therapy is guided by conceptual systems [Pedretti 1996]. One such conceptual system is the Occupational Performance Model, which consists of performance areas, components, and contexts. A therapist using the Occupational Performance Model may influence a client’s performance area or component while considering the context in which the person must operate. The therapist is guided by several treatment approaches in providing assessment and treatment. The therapist may use the biomechanical, sensorimotor, and rehabilitative approaches. The biomechanical approach uses biomechanical principles of kinetics and forces acting on the body. Sensorimotor approaches are used to inhibit or facilitate normal motor responses in persons whose central nervous systems have been damaged. The rehabilitation approach focuses on abilities rather than disabilities and facilitates returning persons to maximal function using their capabilities [Pedretti 1996]. (See Self-Quiz 1-1.) Each approach can incorporate splinting as a treatment intervention, depending on the rationale for splint provision. For example, if a person wears a tenodesis splint to recreate grasp and release to maximize function in activities of daily living, the therapist is using the rehabilitation approach [Hill and Presperin 1986]. If the therapist is using the biomechanical approach, a dynamic (mobilization) hand splint may be chosen to apply kinetic forces to the person’s body. If the therapist chooses a sensorimotor approach, an antispasticity splint may be used to inhibit or reduce tone. Pierce’s notions [Pierce 2003] of contextual and subjective dimensions of occupation are powerful concepts for therapists who appropriately incorporate splinting into a client’s care plan. Understanding how a splint affects a client’s occupational engagement and participation are salient in terms of meeting the client’s needs and goals, which may result in an increased probability of compliance. Contextual dimensions include spatial, temporal, and sociocultural contexts [Pierce 2003]. Subjective dimensions include restoration, pleasure, and productivity.Box 1-1 explicates both contextual and subjective dimensions of occupation. In Chapter 3, Pierce’s framework is used to structure questions for a client interview.

Foundations of Splinting*

Historical Synopsis of Splinting

Occupational Therapy Theories, Models, and Frame-of-Reference Approaches for Splinting

Foundations of Splinting