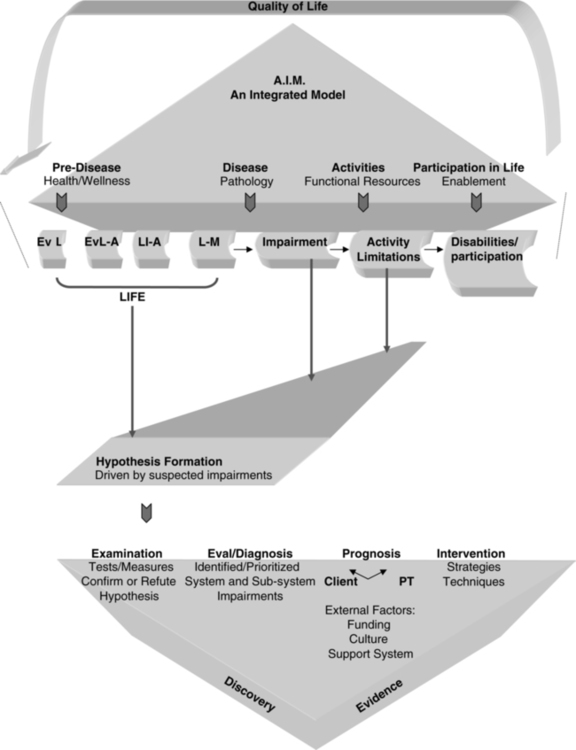

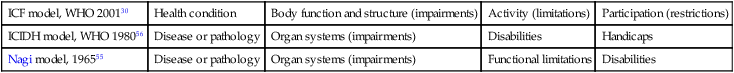

DARCY A. UMPHRED, PT, PhD, FAPTA, ROLANDO T. LAZARO, PT, PhD, DPT, GCS and MARGARET L. ROLLER, PT, MS, DPT After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to: 1. Analyze the interlocking concepts of a systems model and discuss how cognitive, affective, sensory, and motor subsystems influence normal and abnormal function of the nervous system. 2. Use an efficacious diagnostic process that considers the whole patient/client and includes evaluation, examination, diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, and related documentation, leading to meaningful, functional outcomes. 3. Apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to the clinical management of patients/clients with neuromuscular dysfunction. 4. Discuss the evolution of disablement, enablement, and health classification models, neurological therapeutic approaches, and health care environments in the United States and worldwide. 5. Discuss the interactions and importance of the patient, therapist, and environment in the clinical triad. 6. Consider how varying aspects of the clinical therapeutic environment can affect learning, motivation, practice, and ultimate outcomes for patients/clients. 7. Define, discuss, and give examples of a holistic model of health care. A clinical problem-solving approach is used because it is logical and adaptable, and it has been recommended by many professionals during the past 40 years.1–7 The concept of clinical decision making based in problem-solving theory has been stressed throughout the literature over the past decades and has guided the therapist toward an evidence-based approach to patient management. This approach clearly identifies the therapist’s responsibility to examine, evaluate, analyze, draw conclusions, and make decisions regarding prognosis and treatment alternatives.8–24 This book is divided into three sections. Roles that therapists are currently playing and will be asked to play in the future are changing.25–27 Therapists are experts in normal human movement across the life span (see Chapter 3) and how that movement is changed after life events, and with disease or pathological conditions. Therapists realize that health and wellness play a critical role in movement function as a client enters the health care system with a neurological disease or condition (see Chapter 2). In many U.S. states, clients are now able to use direct access for therapy services. In this environment, therapists must medically screen for disease and pathology to determine conditions that are outside of the defined scope of practice, and make appropriate referrals to other medical professionals (see Chapter 7). They must also make a differential diagnosis regarding movement dysfunctions within that therapist’s respective scope of practice (see Chapter 8). Section I has been designed to weave together the issues of evaluation and intervention with components of central nervous system (CNS) function to consider a holistic approach to each client’s needs (see Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 9). This section delineates the conceptual areas that permit the reader to synthesize all aspects of the problem-solving process in the care of a client. Basic to the outcomes of care is accurate documentation of the patient management process, as well as the administration and reimbursement for that process (see Chapter 10). Section II is composed of chapters that deal with specific clinical problems, beginning with pediatric conditions, progressing through neurological problems common in adults, and ending with aging with dignity and chronic impairments. In Section II each author follows the same problem-solving format to enable the reader either to focus more easily on one specific neurological problem or to address the problem from a broader perspective that includes life impact. The multiple authors of this book use various cognitive strategies and methods of addressing specific neurological deficits. A range of strategies for examining clinical problems is presented to facilitate the reader’s ability to identify variations in problem-solving methods. Many of the strategies used by one author may apply to situations presented by other authors. Just as clinicians tend to adapt learning methods to solve specific problems for their clients, readers are encouraged to use flexibility in selecting treatments with which they feel comfortable and to be creative when implementing any therapeutic plan.16 Although the framework of this text has always focused on evidence-based practice and improvement of quality of life of the patient, the terminology used by professionals has shifted from focusing on impairments and disabilities of an individual after a neurological insult (the International Classification of Impairments, Disability and Health [ICIDH]) to a classification system that considers functioning and health at the forefront: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).28 The ICF considers all health conditions, both pathological and non–disease related; provides a framework for examining the status of body structures and functions for the purpose of identifying impairments; includes activities and limitations in the functional performance of mobility skills; and considers participation in societal and family roles that contribute to quality of life of an individual. The personal characteristics of the individual and the environmental factors to which he or she is exposed and in which he or she must function are included as contextural factors that influence health, pathology, and recovery of function.29 The ICF provides a common language for worldwide discussion and classification of health-related patterns in human populations. The language of the ICF has been adopted by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), and the revised version of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice reflects this change.30 Each chapter in this book strives to present and use the ICF model, use the language of the ICF, and present a comprehensive, patient-oriented structure for the process of examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention for common neurological conditions and resultant functional problems. Consideration of the patient/client as a whole and his or her interactions with the therapist and the learning environment is paramount to this process. Chapters in Section II also include methods of examination and evaluation for various neurological clinical problems using reliable and valid outcome measures. The psychometric properties of standard outcome measures are continually being established through research methodology. The choice of objective measurement tools that focus on identifying impairments in body structures and functions, activity-based functional limitations, and factors that create restrictions in participation and affect health quality of life and patient empowerment is a critical aspect of each clinical chapter’s diagnostic process. Change is inevitable, and the problem-solving philosophy used by each author reflects those changes. Section III of the text focuses on clinical topics that can be applied to any one of the clinical problems discussed in Section II. Chapters have been added to reflect changes in the focus of therapy as it continues to evolve as an emerging flexible paradigm within a multiple systems approach. A specific body system such as the cardiopulmonary system (see Chapter 30) or complementary approaches used with interactive systems (see Chapter 39) are also presented as part of Section III. These incorporate not only changes in the interactions of professional disciplines within the Western medical allopathic model of health care delivery, but also present additional delivery approaches that emphasize the importance of cultural and ethnic belief systems, family structure, and quality-of-life issues. Two additional chapters have been added to Section III. Chapter 37 on imaging emphasizes the role of doctoring professions’ need to analyze how medical imaging matches and mismatches movement function of patients. Chapter 38 reflects changes in the role of PTs and OTs as they integrate more complex technologies into clinical practice. Examination tools presented throughout the text should help the reader identify many objective measures. The reader is reminded that although a tool may be discussed in one chapter, its use may have application to many other clinical problems. Chapter 8 summarizes the majority of neurological tools available to therapists today, and the authors of each clinical chapter may discuss specific tools used to evaluate specific clinical problems and diagnostic groups. The same concept is true with regard to general treatment suggestions and problem-solving strategies used to analyze motor control impairments as presented in Chapter 9; authors of clinical chapters will focus on evidence-based treatments identified for specific patient populations. To understand how and why disablement, enablement, and health classification models have become the accepted models used by PTs and OTs when evaluating, diagnosing, prognosing, and treating clients with body system impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions resulting from neurological problems, it is important for the reader to review the evolution of health care within our culture. This review begins with the allopathic medical model because this model has been the dominant model of health care in Western society and forms the conceptual basis for health care in industrialized countries.31 The allopathic model assumes that illness has an organic base that can be traced to discrete molecular elements. The origin of disease is found at the molecular level of the individual’s tissue. The first step toward alleviating the disease is to identify the pathogen that has invaded the tissue and, after proper identification, apply appropriate treatment techniques including surgery, drugs (see Chapter 36), and other proven methods. Levin32 points out that there is a lot that consumers can do for themselves. Most people can assume responsibility to care for minor health problems. The use of nonpharmaceutical methods (e.g., hypnosis, biofeedback, meditation, and acupuncture) to control pain is becoming common practice. The recognition and value of a holistic approach to illness are receiving increasing attention in society. Treatment designed to improve both the emotional and physical needs of clients during illness has been recognized and advocated as a way to help individuals regain some control over their lives (see Chapters 5 and 6). An approach that takes this holistic perspective centers its philosophy on the patient as an individual.33 The individual with this orientation is less likely to have the physician look only for the chemical basis of his or her difficulty and ignore the psychological factors that may be present. Similarly, the importance of focusing on an individual’s strengths while helping to eliminate body system impairments and functional limitations in spite of existing disease or pathological conditions plays a critical role in this model. This influences the roles PT and OT will play in the future of health care delivery and will continue to inspire expanded practice in these professions. The health care delivery system in Western society is designed to serve all of its citizens. Given the variety of economic, political, cultural, and religious forces at work in American society, education of the people with regard to their health care is probably the only method that can work in the long run. With limitations placed on delivery of medical care, the client’s responsibility for health and healing is constantly increasing. The task of PTs and OTs today is to cultivate people’s sense of responsibility toward their own health and the health and well-being of the community. The consumer has to accept and play a critical role in the decision-making process within the entire health care delivery model to more thoroughly guarantee compliance with prescribed treatments and optimal outcomes.34–40 PTs and many OTs today are entering their professional careers at a doctoral level and beginning to assume the role of primary care providers. A requisite of this new responsibility is the performance of a more diligent examination and evaluation process that includes a comprehensive medical screening of each patient/client.41,42 Patient education will continue to be an effective and vital approach to client management and has the greatest potential to move health care delivery toward a concept of preventive care. The high cost of health care is a factor that will continue to drive patients and their families to increase their participation in and take responsibility for their own care.43 Reducing the cost of health care will require providers to empower patients to become active participants in preventing and reducing impairments and practicing methods to regain safe, functional, pain-free control of movement patterns for optimal quality of life. Carlson44 thinks that pressure to change to holistic thinking in medicine continues as a result of a societal change in its perspective of the rights of individuals. A concern to keep the individual central in the care process will continue to grow in response to continued technological growth that threatens to dehumanize care even more. The holistic model takes into account each person’s unique psychosocial, political, economic, environmental, and spiritual needs as they affect the individual’s health. The nation faces significant social change in the area of health care. The coming years will change access to health care for our citizens, the benefits, the reimbursement process for providers, and the delivery system. Health care providers have a major role in the success of the final product. The Pew Health Professions Commission45 identified issues that must be addressed as any new system is developed and implemented. Most, if not all, of the issues involve close interactions between the provider and client. These issues include (1) the need of the provider to stay in step with client needs; (2) the need for flexible educational structures to address a system that reassigns certain responsibilities to other personnel; (3) the need to redirect national funding priorities away from narrow, pure research access to include broader concepts of health care; (4) the licensing of health care providers; (5) the need to address the issues of minority groups; (6) the need to emphasize general care and at the same time educate specialists; (7) the issue of promoting teamwork; and (8) the need to emphasize the community as the focus of health care. There are other important issues, but the last to be included here is mentioned in more detail because of its relevance to the consumer. Without the consumer’s understanding during development of a new system, the system could omit several opportunities for enrichment of design. Without the understanding of the consumer during implementation of a new system, the consumer might block delivery systems because of lack of knowledge. Thus, the delivery of service must be client centered and client and family driven, and the focus of intervention needs to be in alignment with client objectives and desired outcomes.33–36,46,47 Today, as stated earlier,43 this need may be driven more by financial necessity than by ethical and best practice philosophy, but the end result should lead to a higher quality of life for the consumer. Providers are more willing to include the client by designing individualized plans of care, educating, addressing issues of minority groups, and becoming proactive team caregivers.37–40 The influence of these methods extends to the community and leads to greater patient/client satisfaction. The research as of 2011 demonstrates the importance of patient participation, and this body of work is expected to grow. The potential for OTs and PTs to become primary providers of health care in the twenty-first century is becoming a greater reality within the military system as well as in some large health maintenance organizations (HMOs).48–53 The role a therapist in the future will play as that primary provider will depend on that clinician’s ability to screen for disease and pathological conditions, examine and evaluate clinical signs that will lead to diagnoses and prognoses that fall inside and outside of the scope of practice, and select appropriate interventions that will lead to the most efficacious, cost-effective treatment. Disablement models have been used by clinicians since the 1960s. These models are the foundation for clinical outcomes assessment and create a common language for health care professionals worldwide. The first disablement model was presented in 1965 by Saad Nagi, a sociologist.54,55 The Nagi model was accepted by APTA and applied in the first Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, which was introduced in 2001.30 In 1980 the ICIDH was published by the World Health Organization (WHO).56 This model helped expand on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), which has a narrow focus based on categorizing diseases. The ICIDH was developed to help measure the consequences of health conditions on the individual. The focus of both the Nagi and the ICIDH models was on disablement related to impaired body structures and functions, functional activities, and handicaps in society (Figure 1-1). The WHO ICF model28 evolved from a linear disablement model (Nagi, ICIDH) to a nonlinear, progressive model (ICF) that encompasses more than disease, impairments, and disablement. It includes personal and environmental factors that contribute to the health condition and well-being of individuals. The ICF model is considered an enablement model as it not only considers dysfunctions, but helps practitioners and researchers understand and use an individual’s strengths in the clinical presentation. Each of these models provides an international standard to measure health and disability, with the ICF emphasizing the social aspects of disability. The ICF recognizes disability not only as a medical or biological dysfunction, but as a result of multiple overlapping factors including the impact of the environment on the functioning of individuals and populations. The ICF model is presented in Table 1-1 and discussed in greater depth in Chapters 4, 5, and 8. It is easy to integrate the ICF model into behavioral models for the examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention of individuals with neurological system pathologies (see Figure 1-1). Whether an individual’s activity limitations, impairments, and strengths lead to a restriction in the ability to participate in life activities, the perception of poor health, or restriction in the ability to adapt and adjust to the new health condition will determine the eventual quality of life of the person and the amount of empowerment or control he or she will have over daily life. The importance of the unique qualities of each person and the influence of the inherent environment helped to drive changes to world health models. The ICF is widely accepted and used by therapists throughout the world and is now the model for health in professional organizations such as APTA in the United States.30 As world health care continues to evolve, so will the WHO models. The sequential evolution of the three models is illustrated in Table 1-1. This evolution has created an alignment with what many therapists and master clinicians have long believed and practiced—focus on the patient, not the disease. The shift from disablement to enablement models of health care is a reflection of this change in perspective. TABLE 1-1 ENABLEMENT AND DISABLEMENT MODELS WIDELY ACCEPTED THROUGHOUT THE WORLD OVER THE LAST 50 YEARS* *Placed in table form to show similarities in concepts across the models. Please note that the ICF is a nonlinear, progressive model of enablement and includes contextual factors (personal and environmental) that contribute to the well-being of the individual. Also refer to Chapter 8 for a more detailed discussion of the ICF model. Three conceptual frameworks for client-provider interactions are commonly used in the current health care delivery system. Each framework serves a different purpose and is used according to the goals of the desired outcome and the group interpreting the results (Figure 1-2). The four primary conceptual frameworks include (1) the statistical model, (2) the medical diagnostic model, (3) the behavioral or enablement model, and (4) the philosophical or belief model. Physicians are educated to use a medical disease or pathological condition diagnostic model for setting expectations of improvement or lack thereof. In patients with neurological dysfunction, physicians generally formulate their medical diagnosis on the basis of results from complex, highly technical examinations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), computerized axial tomography (CAT or CT scan), positron emission tomography (PET scan), evoked potentials, and laboratory studies (see Chapter 37). When abnormal test results are correlated with gross clinical signs and patient history such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or head trauma, a medical diagnosis is made along with an anticipated course of recovery or disease progression. This medical diagnostic model is based on an anatomical and physiological belief of how the brain functions and may or may not correlate with the behavioral and enablement models used by therapists. The behavioral or enablement model evaluates motor performance on the basis of two types of measurement scales. One type of scale measures functional activities, which range from simple movement patterns such as rolling to complex patterns such as dressing, playing tennis, or using a word processor. These tools identify functional activities or aspects of life performance that the person has been or is able to do and serve as the “strengths” when remediating from activity limitations or participation restrictions. The second scale looks at bodily systems and subsystems and whether they are affecting functional movement. These measurement tools must look at specific components of various systems and measure impairments within those respective areas or bodily systems. For example, if the system to be assessed is biomechanical, a simple tool such as a goniometer that measures joint range of motion might be used, whereas a complex motion analysis tool might be used to look at interactions of all joints during a specific movement. These types of measurements specifically look at movement and can be analyzed from both an impairment and an ability perspective. Chapter 8 has been designed to help the reader clearly differentiate these two types of measurement tools and how they might be used in the diagnosis, prognosis, and selection of intervention strategies when analyzing movement. Therapists appreciate a statistical model through research and acceptance of evidence-based practice. A third-party payer also uses numbers to justify payment for services or to set limits on what will be paid and for specific number of visits that will be covered. Therapists also appreciate physicians’ knowledge and perspective of disease and pathology because of the effect of disease and pathology on functional behavior and the ability to engage and participate in life. On the other hand, third-party payers and physicians may not be aware of the models used by OTs and PTs. It is therefore critical that therapists make the bridge to physicians and third-party payers because research has shown that interdisciplinary interactions help reduce conflict between professionals and provide better consistency for the patient.57,58 It is a medical shift in practice to recognize that patient participation plays a critical role in the delivery of health care. The importance of the patient and what each individual brings to the therapeutic environment has been recognized and incorporated into patient care by rehabilitation professionals.37–40 This integration and acceptance will guide health care practice well into the next decade. The need for students to develop problem-solving strategies is accepted by faculty across the country and by the respective accrediting agencies of health professionals. Unfortunately, we may not be educating students to the level of critical thinking that we hope.59,60 The need for this cognitive skill development in clinicians may be emergent as both physical and occupational therapy professions have moved or plan to move to a doctoring professions.49 All health-related professions must evolve as patient care demands increase, delineation of professional boundaries become less clear, and collaboration becomes a more integral factor in providing high-quality health care. All previously presented models (statistical, medical, behavioral, or belief) can stand alone as acceptable models for health care delivery (see Figure 1-2, A) or can interact or interconnect (Figure 1-2, B). These interconnections should validate the accuracy of the data derived from each model. The concept of an integrated problem-solving model for neurological rehabilitation must also identify the functional components within the CNS (Figure 1-2, C). A model that identifies the three general neurological systems (cognitive, emotional, motor) found within the human nervous system can be incorporated into each of the other models separately or when they are interconnected (Figure 1-2, D). A systems or behavioral model that focuses on the neurological systems is much more than just the motor systems and their components, or cognition with its multiple cortical facets, or the affective or emotion limbic system with all its aspects. The complexity of a neurological systems model (Figure 1-3), whether used for statistics, for medical diagnosis, for behavioral or functional diagnosis, or for documentation or billing, cannot be oversimplified. As the knowledge bank regarding central and peripheral system function increases, as well as knowledge about their interactions with other functions within and outside the body, the complexity of a systems model also enlarges.61 The reader must remember that each component within the nervous system has many interlocking subcomponents and that each of those components may or may not affect movement. Therapists use these movement problems as guidelines to establish problem lists and intervention sequences. These components, considered impairments or reasons why someone has difficulty moving, are critical to therapists but are of little concern within a general statistics model and may have little bearing on the medical diagnosis made by the physician. In addition to the Western health care delivery paradigms are the interlocking roles identified within an evolving transdisciplinary model (Figure 1-4). Within this model, the environments experienced by the client both within the Western health care delivery system and those environments external to that system are interlocking and forming additional system components; they influence one another and affect the ultimate outcome demonstrated by the client. Because all these once-separate worlds encroach on or overlay one another and ultimately affect the client, practitioners are now operating in a holistic environment and must become open to alternative ways of practice. Some of those alternatives will fit neatly and comfortably with Western medical philosophy and be seen as complementary. Evidence-based practice, which used linear research to establish its reliability and validity, has provided therapists with many effective tools both for assessment and treatment, but we still are unable to do similar analyses while simultaneously measuring multiple subsystem components. We can measure tools and interventions across multiple sites but are a long way from truly understanding the future of best practice. Other evaluation and treatment tools may sharply contrast with Western research practice, having too many variables or variables that cannot be measured; therefore arriving at evidence-based conclusions seems an insurmountable problem. In time many of these other assessment tools and intervention strategies may be accepted, once research methods have been developed to show evidence of efficacy, or they may be discarded for the same reason. Until these approaches have gone beyond belief in their effects, therapists will always need to expend additional focus measuring quantitative outcomes and analyzing accurately functional responses. Because the research is not available does not mean the approach has no efficacy (see Chapter 39). Thus the clinician needs to learn to be totally honest with outcomes, and quality of care and quality of life remain the primary objective for patient management. Today, models that incorporate health and wellness have been added to these disablement and enablement models to delineate the complexity of the problem-solving process used by therapists62,63 (see Chapter 2). This delineation should reflect accurate behavioral diagnoses based on functional limitations and strengths, preexisting system strengths and accommodations, and environmental-social-ethnic variables unique to the client. Similarly, it includes the family, caregiver, financial security, or health care delivery support systems. All these variables guide the direction of intervention64 (Figure 1-5). These variables will affect behavioral outcomes and need to be identified through the examination and evaluation process. Many of these variables may not relate to the CNS disease or pathological condition medical diagnosis to which the patient has been assigned. The client brings to this environment life experiences. Many of these life events may have just been a life experience; others may have caused slight adjustments to behavior (e.g., running into a tree while skiing out of patrolled downhill ski areas and then never doing it again), some may have caused limitations (e.g., after running into the tree, the left knee needed a brace to support the instability of that knee during any strenuous exercising), or caused adjustments in motor behavior and emotional safety before that individual entered the heath care delivery system after CNS problems occurred. The accommodations or adjustments can dramatically affect both positively and negatively the course of intervention. To quickly accumulate this type of information regarding a client, the therapist must become open to the needs of the client and family. This openness is not just sensory, using eyes and ears, but holistic and includes a bond that needs to and should develop during therapy (see Chapters 5 and 6). Efficacy has been defined as the “ability of an intervention to produce the desired beneficial effect in expert hands and under ideal circumstances.”65 When any model of health care delivery is considered, the question the therapist must ask is “Which model will provide the most efficacious care?” Therapists may not diagnose a pathological disease or its process, but they are in a position of responsibility to examine body systems for existing impairments and to analyze normal movement to determine appropriate interventions for activity-based functional problems. Some differences in this responsibility may exist between practice settings. Therapists in private practice act independently to select both examination tools and intervention approaches that are efficacious and prove beneficial to the patient. Within a hospital-based system, therapists may be expected to use specific tools that are considered a standard of care for that facility, regardless of the therapy diagnosis and treatment rendered. In some hospitals and rehabilitation settings a clinical pathway may be employed that defines the roles and responsibilities of each person on a multidisciplinary team of medical professionals. Regardless of which clinical setting or role the therapist plays, it is always the responsibility of the therapist to be sure that the plan of care is appropriate, is consistent with the medical and therapy diagnoses, meets the needs of the patient, and renders successful outcomes. If the needs of the particular client do not match the progression of the pathway, it is the therapist’s responsibility to recommend a change in the client’s plan of care. Efficacy does not come because one is taught that an examination tool or intervention procedure is efficacious, it comes from the judicious use of tools to establish impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions, identify movement diagnoses, create functional improvements, and improve quality of life in those individuals who have come to us for therapy. Today’s health care climate demands that the therapeutic care model be efficient, be cost-effective, and result in measurable outcomes.66 The message being given today might be considered to reflect the idea that “the end justifies the means.” This premise has come to fruition through the linear thought process of established scientific research. Yet when a holistic model is accepted into practice it becomes apparent that outcome tools are not yet available to simultaneously measure the interactions of all body systems that make up the patient, making it difficult to apply models that purport to balance quality and cost of care. Thus we must guard against the reductionist research of today, which has the potential to restrain our evolution and choice of therapeutic interventions. Sometimes the individuals making decisions about what to include and what to eliminate with regard to patient services are not health care providers. They are individuals who are trained to use evidence gained from numbers or statistics to make their decision and do not have knowledge of the patient, his or her situation, or the effect of the neurological condition on function. Therapists should always be able to defend their choice and use of intervention approaches. This becomes even more relevant as the cost of health care rises. Evidence-based practice is basic to the care process.30,67,68 Clinicians need to identify which of their therapeutic interventions have demonstrated positive outcomes for particular clinical problems or patient populations and which have not.69 Those that remain in question may still be judged as useful. The basis for that judgment may be a client satisfaction variable that has become a critical variable for many areas in health care delivery.70,71 But there is still limited information on patient satisfaction with PT and OT services, although within the last few years more information has become available.72–76 Although patient satisfaction is a critical variable within the ICF model, there are always problems with satisfaction and outcomes versus identification of specific measurable variables within the CNS that are affecting outcomes. One reason for the problem of integrating patient satisfaction with PT and OT services within a neurorehabilitation environment is the large discrepancy between the variables we can measure and the variables within the environment that are affecting performance. For example, when a neurosurgeon once asked the question to one of the editors, “Do you know how to prove the theories of intervention you are teaching?” The answer was, “Yes, all I need are two dynamic PET units that can be worn on both the client’s and the therapist’s heads while performing therapeutic interventions. I also need a computer that will simultaneously correlate all synaptic interactions between the therapist and the client to prove the therapeutic effect.” The physician said, “We don’t have those tools!” The response was, “You did not ask me if the research tools were available, only if I know how to obtain an efficacious result.” Thus, the creativity of the therapist will always bring the professions to new visions of reality. That reality, when proven to be efficacious, assists in validating the accepted interventions used by the professional. The therapist today has a responsibility to provide evidence-based practice to the scientific community…but more important, also to the client. Therapeutic discovery usually precedes validation through scientific research. This discovery leads the way to, first, effective interventions, followed by efficacious care. If research and efficacious care always have to come before the application of therapeutic procedures, nothing new will evolve because discovery of care is most often, if not always, found in the clinic during interaction with a client. Thus the range of therapeutic applications will become severely limited and the evolution of neurological care stopped if that discovery is ignored because there is no efficacy as defined by today’s research models. However, performing interventions because the approaches “have been typically done in the past” could be wasteful and irresponsible.

Foundations for clinical practice*

The changing world of health care

In-depth analysis of the holistic model

Therapeutic model of neurological rehabilitation within the health care system

Traditional therapeutic models

Physical and occupational therapy practice models

ICF model, WHO 200130

Health condition

Body function and structure (impairments)

Activity (limitations)

Participation (restrictions)

ICIDH model, WHO 198056

Disease or pathology

Organ systems (impairments)

Disabilities

Handicaps

Nagi model, 196555

Disease or pathology

Organ systems (impairments)

Functional limitations

Disabilities

Conceptual frameworks for client/provider interactions

Medical diagnostic model

Behavioral or enablement model

Philosophical or belief model

Efficacy

Foundations for clinical practice

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree