CHAPTER 9 Footwear assessment

Introduction

What do patients want from their footwear?

Patients may subconsciously use a list of preferential features which may include:

The patient’s perspective may be summarised in the word ‘comfort’. Comfort is a term which relates to a lack of discomfort or pain and is directly related to sensitivity levels. It seems that in comparison with the hand, the foot has much lower sensitivity. Table 9.1 shows the differences in two-point discrimination at specific distances on sites on the hand and foot when monofilaments are applied (Goonetilleke & Luximon 2001).

Table 9.1 Sensitivity to Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments and two-point discrimination at points in the hand and foot

| Site | Touch sensitivity measured with Semmes–Weinstein monofilament (in mg) | Two point discrimination (in mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Middle finger | 6.8 | 2.5 |

| Palm | 20.1 | 11.5 |

| Sole | 35.9 | 22.5 |

| Hallux | 36.7 | 12.0 |

Parts of the shoe

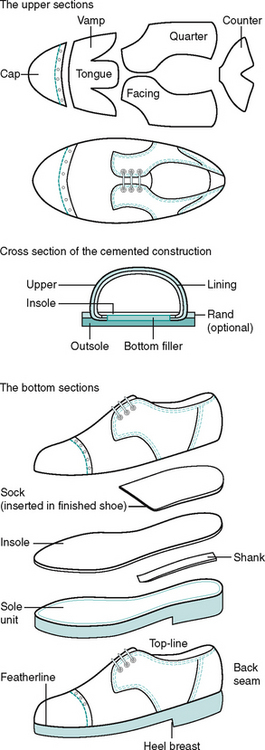

Toe puff (stiffener)

The toe puff is a stiffener between the vamp and the lining. It prevents the vamp collapsing and lifts it over the toes. Retail footwear often contains toe puffs which are extended proximally to cover part, or all, of the dorsal surface of the toes. Such toe puffs may exert pressure on the dorsal surface of clawed or hammered toes. Some footwear is made with toe puffs with additional strength, sometimes out of metal to give added strength and protection (e.g. industrial boots).

Tongue

The tongue is usually cut as an integral part of the vamp. It may or may not be padded. It is usually attached to the vamp only at its base, but it may also be made in ‘bellows’ form. In this form, the tongue material is part of the vamp, but it contains additional wings that are stitched to the quarters in a modified Gibson (Derby) construction (Fig. 9.1). This design allows for variable volume of the foot and so is useful for patients with foot and ankle oedema. A well-padded tongue is often important in patients with tarsometatarsal arthritis to reduce pressure over bony prominences.

Heel counters

Heel counters may be extended medially, laterally, and proximally upwards from the ankles in boots. Heel counters provide stability and offer some control to the rear part of the foot during heel strike. Counters may also be made of extra strong material for additional reinforcement. Medial reinforcement is useful in pronatory syndromes and mid-foot Charcot neuro-arthropathy. Proximal reinforcement is used in cases of ankle weakness or deformity.

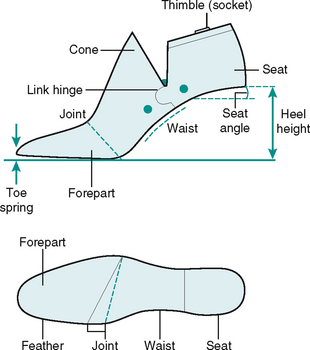

The last

The last is the model form (Fig. 9.2) around which the shoe is made. Lasts are usually made of polyurethane, although wooden lasts may be used for high-quality, high-cost bespoke footwear.

Last measurements and sizing

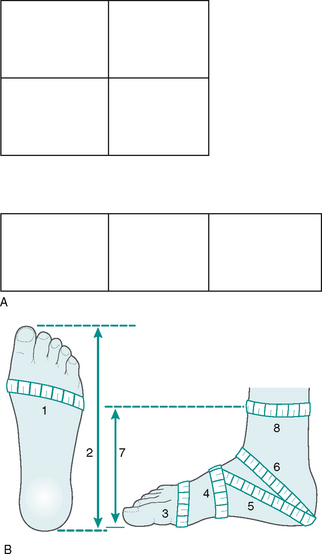

The length of the last will equate with the finished length of the shoe that is made on it. The foot width and girth measurements are taken at several points. The widest point on the last will equate with the width of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal joints. The width from medial to lateral across the plantar surface of the heel directly beneath the malleoli will also be transferred to the measurement at the corresponding point on the last. Girth measurements are taken at a minimum of five points on the foot to correspond with last dimensions. These points include the circumference of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal joints, the circumference of the foot immediately behind the metatarsal heads (known as the waist measurement), and the circumference of the foot at the instep – in the position of the cuneiform bones. Girth measurements will also be taken from the back of the heel at the plantar/retrocalcaneal border to the dorsal surface of the ankle joint and from the same point at the back of the heel to the point at which the instep girth was taken. These measurements are known as the short and long heel measurements, respectively (see Fig. 9.6B).

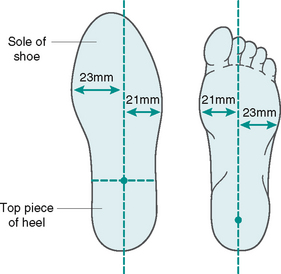

The flare

This describes the curve or contour of the longitudinal bisection of the last. A last may be inflared, outflared or neutral. In order to describe the flare, a line which longitudinally bisects the heel of the last is carried forwards to the front of the last. The last is said to be inflared when the medial portion of the last across the treadline area is wider than that on the lateral side. The last is said to be outflared when the portion on the lateral side of the treadline is greater than that on the medial. When both sides are of equal width the last is said to have a neutral flare (Fig. 9.3).

For reasons of cosmesis most lasts (and therefore most shoes) are inflared. Some orthopaedic shoes and trainers are of neutral flare. Few shoes are made with an outflare – on rare occasions shoes are made with an outflare to correct in-toeing in children.

The ideal shoe – the clinician’s perspective

What to advise patients about footwear

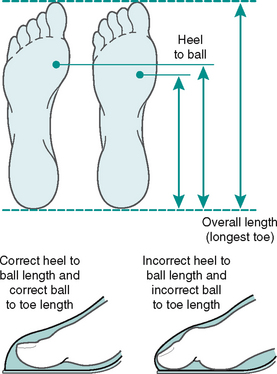

The first and probably most evident feature is that footwear should fit the feet they are intended for. The length of the shoe should accommodate the longest part of the foot always remembering that digital formulae are not standard and that in some patients one or more of the lesser toes may be longer than the hallux. Length should then be subdivided into the length from the heel to the first metatarsophalangeal joint and the length from the first metatarsophalangeal joint to the toes (Fig. 9.4).

Shoe width increases incrementally with length and patients with wide feet often choose shoes that are too long for them to obtain adequate width. This also means that the metatarsophalangeal joints will be positioned proximal to the shoe treadline and shoe flexion will not correspond to foot flexion and the shoe will acquire additional toe spring and the vamp will crease. If the shoe contains a shank, the shank may break through the outersole. This is because the relationship between the heel height and the treadline has been changed as the foot requires the shoe to flex in a more proximal position than it was designed to do (Fig. 9.5).

The shoe should be of correct width and girth at the metatarsal heads and of correct girth at the instep. Several other girth measurements need to be matched if the shoe is to fit properly (Fig. 9.6). The long heel measurement is perhaps one of the most important in obtaining a good fit and it dictates the positioning of the instep fastening. It is also necessary to remember that the shoe needs to change shape with the foot in gait. The time of the day when taking measurements is also important since normal daytime changes result in a 3% increase in foot volume (Janisse et al 1995) and vigorous exercise can cause an increase in foot volume by 8% (Merriman & Tollafield 1997). The shoe should be large enough to allow for changes in dimension as the day progresses and should also allow for changes in volume required by variation in hosiery, activity, or to accommodate dressings/padding where needed. If the patient needs to wear orthoses, the shoe needs to be able to accommodate them. The shoe should be of adequate width and depth and there should be no localised tight spots. The heel of the shoe should be broad based for stability on heel contact. There should be a functional fastening to hold the foot back in the shoe and to prevent impaction of the toes against the front of the shoe. The topline of the shoe should fit snugly and should not gape. It should not irritate the malleoli or Achilles tendon.

Shoe style

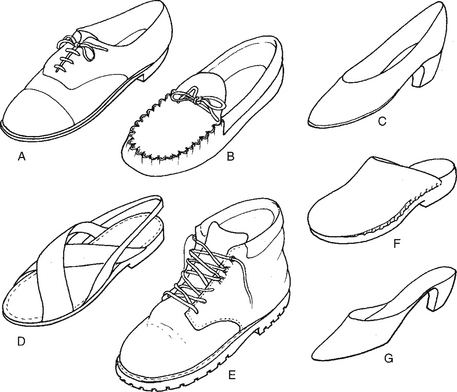

There are seven basic shoe styles (Fig. 9.7). The choice of shoe style should be based on the fact that the foot changes in dimension during the various stages of the gait cycle. If the shoe is to be large enough to accommodate the fully loaded foot then it will need to be strapped or laced onto the foot otherwise it will fall off during the swing phase of the gait cycle when the foot is unloaded and of different dimension. Slip-on or court shoes will need to be wedged onto the foot and if they are to stay on the foot during the swing phase they will be too small for the fully loaded foot. They only stay on the foot by a gripping action of the toes. This can lead to the development of corn or callus on prominent toe joints and in some cases can lead to toe deformities through the constant clawing action. Functional straps or laces provide a mechanism for holding the foot back in the shoe and minimising the forward slip of the foot into the toe space of the shoe causing compression of the forefoot.

Figure 9.7 The seven basic shoe styles: A lace-up, B moccasin, C court, D sandal, E boot, F clog and G mule.

The heel height should ideally be about 2.5 cm but no more than 4 cm. The higher the heel the greater the forward displacement of body mass onto the metatarsal heads. An elevated heel also has the effect of changing the body’s centre of gravity, and to compensate for this the ankles plantarflex (passively) and there is reduced supination at push off. In addition, the stance knee and hips flex resulting in reduced swing knee flexion (De Lateur et al 1991, Esenyel et al 2003, Gefen et al 2002, Lee et al 1990). There may then be a compensatory action in the lumbar spine. This can lead to discomfort and to arthritic changes in the affected joints. The same basic principles apply to children’s footwear with one additional feature, that of growth allowance. The amount of growth allowance will depend on the child’s foot length. This will be less in small sizes and up to 14 mm in larger children’s sizes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree