Football

Richard A. Parker

Stephen Daquino

Naresh C. Rao

Steven J. Karageanes

OVERVIEW

The popularity of football has grown tremendously since its inception. The first game played in America is believed to have been played in 1869 between Princeton and Rutgers, following soccer rules. The first official rules for American football were written in 1876. Over the next 15 years, rugby rules seeped into the game design, and the sport gradually took a new shape, while its progenitor in America went from football to soccer, despite being called football by the rest of the world (1).

Injuries and deaths occurred near the turn of the twentieth century at alarming rates, necessitating a governing body to be created by President Theodore Roosevelt. First called the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, it was renamed the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1910. Over many years the NCAA changed football, instilling safety measures such as helmets, pads, and rule changes designed to reduce catastrophic injury.

Today, football is arguably the most popular sport in the United States, with an estimated 1.8 million male participants and millions more people who are spectators. The sport spans Pop Warner and Pee Wee youth leagues through high school and collegiate football. Elite professional football has been played in the National Football League, while lesser professional leagues have come and gone throughout the years. The Canadian Football League, Arena football, and NFL Europe are three present-day manifestations that still play and compete.

The National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research states there were approximately 1,800,000 participants in football during the 2000 season on all levels of participation in the United States. Associated with an increase in participation, however, is a natural increase in injury rates. In 1931, the American Football Coaches Association initiated the first annual survey of football fatalities. The surveys were started with the intention of making the sport a safer and more enjoyable activity for its participants. This monitoring of injury rates has led to the development of improvements in equipment, medical care, and coaching techniques. As a direct result of injury monitoring, in 1976 the tackling or blocking technique known as spearing (making first contact with another player with the head) was made illegal.

The year 1990 marked a record year in injury surveillance. It was the first year since the beginning of surveillance that no fatalities on any level of the sport were reported. From the years 1931 to 1965 there were 608 fatalities reported on all levels of competitive football. In 1968, 36 total deaths were reported, and that number was reduced to 5 total in 2002: 3 of those 5 were reported in high school athletes, which is the level at which most fatalities occur. The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System estimated there were 355,247 total injuries related to football reported from emergency rooms in the United States in 1998, an increase from 334,420 in 1997 (2).

By virtue of its combative nature, speed, and high-energy collisions, football participation results in a high incidence of traumatic injury. However, there are many nontraumatic, gradual-onset injuries that occur in football athletes which can negatively affect their playing ability, even to the point of missing participation (3). The application of manual medicine techniques

and exercise therapy in football players can minimize and even prevent injury as well as optimize performance on the field.

and exercise therapy in football players can minimize and even prevent injury as well as optimize performance on the field.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE

Football, the same as many other sports, requires both aerobic and anaerobic fitness in order for participants to be competitive on all levels. Football is a collision sport with medium static and dynamic demands (4). Plays typically last from 3 to 10 seconds, with a rest period in between. Weight training is required to build strength and size, particularly in players required to block other players, such as offensive and defensive linemen, fullbacks, tight ends, and linebackers. Agility, flexibility, and speed are qualities important to all players, but particularly to those athletes required to handle the ball and those sprinting on virtually every play such as halfbacks, receivers, and defensive backs.

The majority of injuries are traumatic and acute, so initial evaluation should take this into consideration. Football elucidates the issue of playing hurt versus playing injured, since players will play through pain as long as they feel confident they are not necessarily injured. How these terms are defined and how far these definitions go in the eyes of the clinician and player is the challenge. Most trauma and injuries are straightforward, such as simple fractures, sprains, and contusions. Many of these injuries can be protected, padded, splinted, or wrapped, and the player will compete while playing hurt.

Most complex or significant injuries are straightforward in initial management once a preliminary diagnosis is made; apply the RICE protocol (rest, ice, compression, and elevation), make the decision whether the athlete will return to play immediately or sit out, and hold him out of practice until he is physically able to perform. Prognosticating return to play can be more difficult. Teams base personnel decisions on the eventual availability or inactivity of a player, and most of their decisions are based upon what the physician and trainer report to the head coach. A conservative approach in the general population usually works fine, but in the competitive football world, few games are played, and consequently, their individual importance is magnified. Therefore, players are less tolerant of missing one game than in a longer-season sport like baseball. Players usually have 7 days of preparation in-between games, so the challenge for the medical staff is getting them ready for the game. The gladiator mentality allows many college and professional players to play through injuries and pain, which is a blessing and a curse when administering treatment.

THROWING MECHANICS VERSUS BASEBALL

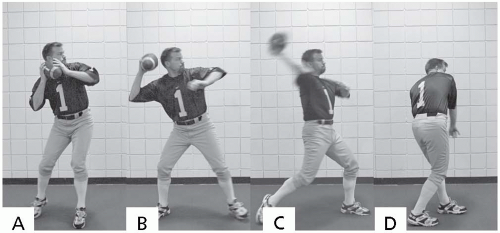

The quarterback is the only position in football whose main purpose is to throw the ball to another player (save for the occasional trick play by a teammate). Accuracy and velocity are just as important for the quarterback as for the baseball pitcher. However, there are several important differences in mechanics, described well by Meister (Fig. 30.1) (5):

The mechanics of a football pass are closer to a baseball catcher than a pitcher. Instead of the full windup and follow-through that a pitcher needs, the cocking phase of the quarterback is less dramatic, usually coming just behind the ear, and the elbow extends fully during the follow-through. This method allows the quarterback to throw quick passes from various positions and situations, even while on the run. The pitcher has no such requirements, and their target at home plate never moves during the game. This also unloads the elbow from the compressive rotational forces of the pitcher (5,7).

The heavier weight of the football affects shoulder position and stresses in all phases (6). Quarterbacks rotate their shoulders sooner and achieve maximum external rotation earlier in the throwing cycle than do pitchers, probably allowing more time for acceleration during internal rotation. However, even with the increased time afforded internal rotation, internal rotation velocities are significantly less when throwing a football,

7,600 degrees per second in baseball versus 5,000 degrees per second in football (5).

The heavier football also forces the quarterback to lead more with the elbow, which is undesirable in baseball pitching mechanics. Increased shoulder horizontal adduction coupled with increased elbow flexion is needed in the late cocking phase to decrease the impact of the heavier football by shortening the lever arm, lessening the potential load on the shoulder (5).

Quarterbacks throw in a more erect position, while pitchers fall forward with the torso at delivery. This decreases the contribution of the hip and legs in the throw, but it also results in decreased arm velocity. The erect finish of the quarterback also keeps him out of a more vulnerable position, that is, bent over and unable to escape impact from an oncoming defensive rush. The overall lower torques and forces generated on the throwing shoulder of the football player may also account for the lower incidence of shoulder injuries in football (5).

The workload on a quarterback is typically less than for a pitcher. The quarterback rarely throws more than 30 or 40 passes per game, and velocity can vary greatly, depending on whether a short lob screen, medium-range bullet, or a deep lofting bomb is needed. Humeral internal rotation speeds are 3 to 4.5 times faster in baseball than in football, and elbow extension velocity is 2 to 3 times faster in baseball as well.

Plus, the starting pitcher throws to near maximum velocity or arm speed during every pitch for 100 to 120 pitches. Football games are played only once a week, whereas starting pitchers pitch twice and a reliever may pitch three or four times in a week. Pitchers also stress their arms with numerous types of spin put on the ball as it is delivered in order to create extra movement during the trajectory. On the other hand, the quarterback tries to throw a tight spiral pass with minimal or no extra movement, and variety comes from the trajectory and velocity, neither of which is disguised for the other team before release.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) sprains of the elbow have a different impact in football than in baseball. They are merely a nuisance to the football player, even a quarterback. A study of MCL injuries over 5 years in the National Football League showed 19 acute MCL sprains, including two quarterbacks, and none required surgery (7). In fact, only four even missed games. In baseball, MCL injuries are severe, season-ending injuries. Complete tears require reconstruction, 12 to 15 months of rehabilitation before returning to the sport, and a 70% to 90% chance of returning to the previous level of competition, while partial MCL tears had a 42% failure rate of nonoperative treatment in returning to the mound, according to one study (8). This further proves the lower load that the shoulder and elbow carry in football throwing mechanics.

FIGURE 30.1. The phases of the football throw. A, Early cocking. B, Late cocking. C, Acceleration. D, Follow-through. (From Kelly BT, Backus SI, Warren RF, et al. Electromyographic analysis and phase definition of the overhead football throw. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:837-844.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|