22.1 Anatomy

William M. Falls

Gail A. Shafer-Crane

The pelvic girdle is composed of three joints that work together to provide mobility for the lower limb and stability for the body. These include the acetabular-femoral (hip) joint, the sacroiliac joint, and the pubic symphysis. The sacroiliac joint and pubic symphysis are almost totally immovable joints, while the hip joint is very mobile. Anatomy of the hip and pelvis is presented in detail in major anatomic textbooks (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6).

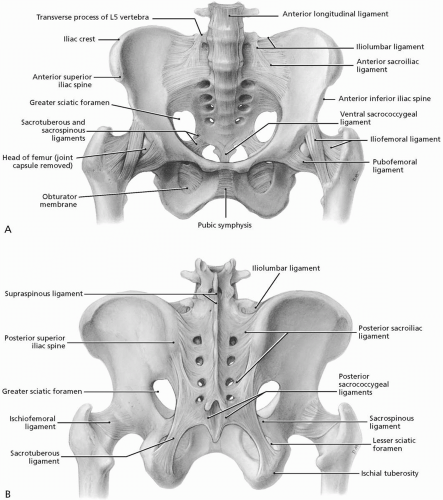

Several bony structures can be palpated as one examines the pelvic girdle. Beginning anteriorly, the subcutaneous anterior superior iliac spine can be easily palpated at the anterior end of the iliac crest (

Fig. 22.1.1A). The iliac crest extends posteriorly from the anterior superior iliac spine to terminate at the posterior superior iliac spine, which lies directly deep to the dimples just superior to the buttocks. The iliac crest is subcutaneous and serves as the point of attachment for several muscles. Along the lateral lip of the iliac crest and approximately 7.5 cm from its apex lies the iliac tubercle, which marks the widest point on the crest. An imaginary transverse line connecting the tops of the iliac crests on each side crosses between the spinous processes of the L4 and L5 vertebrae.

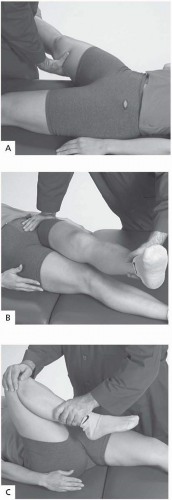

The posterior edge of the greater trochanter of the femur can be easily palpated along the superior lateral aspect of the thigh (

Fig. 22.1.2). The anterior and lateral portions of the greater trochanter are covered by the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius muscles and are less available for palpation. Following down along the inguinal crease medially and obliquely from the anterior superior iliac spine one can palpate the pubic tubercle deep to the pubic hair and mons pubis. It should be noted that the pubic tubercle and the superior edge of the greater trochanter lie on the same transverse plane.

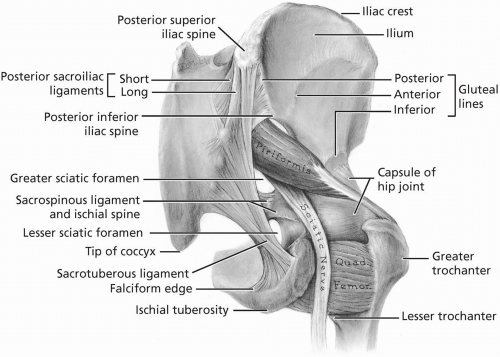

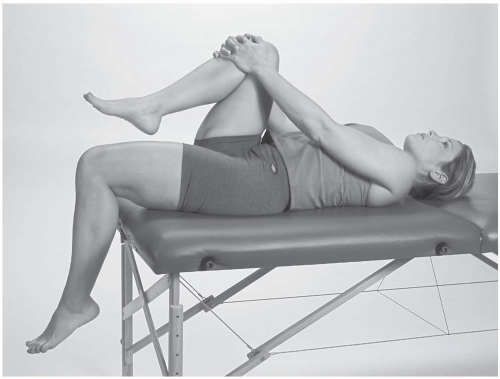

Posteriorly, the ischial tuberosity lies in the middle of the buttocks at the level of the gluteal fold (

Fig. 22.1.3). It is covered by the gluteus maximus muscle and fat and can only be palpated when the muscle moves superiorly during hip flexion. The ischial tuberosity lies on the same transverse plane as the lesser trochanter, which is not palpable and arises from the posterior medial surface of the proximal femur.

The sacroiliac joint is not palpable and the center of the joint is located at the level of the S2 segment of the sacrum. It is crossed by an imaginary transverse line connecting the posterior superior iliac spines on each side. Other important bony landmarks that are not palpable include the greater and lesser sciatic notches, the ischial spine and the acetabulum of the hip bone, and the head and neck of the femur.

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket synovial joint. At this joint the head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum. The depth of the acetabulum is increased by the fibrocartilaginous acetabular labrum, which attaches to the bony rim of the acetabulum and the transverse acetabular ligament. A strong fibrous capsule surrounds the joint, which attaches proximally to the rim of the acetabulum and the transverse acetabular ligament and distally to the intertrochanteric line of the femur anteriorly and the neck of the femur

posteriorly. Most of the fibers of the fibrous capsule take a spiral course from the hip bone to the femur. The synovial membrane, which lines the fibrous capsule, also covers the neck of the femur, which is intracapsular, and the nonarticular portion of the acetabulum as well as the ligament of the femoral head. The strong Y-shaped iliofemoral ligament reinforces the fibrous capsule anteriorly and is extremely important in preventing overextension of the hip during standing by screwing the head of the femur into the acetabulum.

The fibrous capsule is reinforced anteriorly and inferiorly by the pubofemoral ligament,

which tightens during extension and abduction of the hip, thereby preventing overabduction at the joint. The ischiofemoral ligament reinforces the hip joint posteriorly where it screws the head of the femur medially into the acetabulum during extension, thereby preventing hyperextension of the joint. The intracapsular ligament of the femoral head, which connects the acetabulum to the femoral head, is weak and usually contains a small artery to the head of the femur. The hip joint movements are flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, medial-lateral rotation, and circumduction.

The joint receives its blood supply from branches of the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries, the artery of the femoral head, and a branch of the obturator artery. Branches of the femoral and sciatic nerves, the obturator nerve, and the superior gluteal nerve innervate the hip joint.

The sacroiliac joint is an extremely strong weight-bearing synovial joint between the articular surfaces of the ilium and the sacrum. These surfaces display irregular elevations and depressions, which serve to interlock the bones. Interosseous and anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments support the joint. The sacroiliac joint allows for very little mobility because of its role in transmitting the weight of the body to the hip bones. Movement at the sacroiliac joint is limited to gliding and rotatory movements when the joint is subject to considerable force. The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments allow only limited movement to the inferior end of the sacrum, thereby giving resilience to this region when the vertebral column sustains sudden weight increases.

The relatively immobile pubic symphysis is a fibrocartilaginous joint between the bodies of the pubic bones on the anterior midline. The fibrocartilaginous interpubic disc connects the two bones. The joint is reinforced superiorly by the superior pubic ligament and inferiorly by the arcuate pubic ligament.

Five anatomic regions around the hip and pelvic regions must be emphasized: (

1) femoral triangle, (

2) greater trochanter, (

3) sciatic nerve, (

4) iliac crest, and (

5) hip and pelvic muscles.

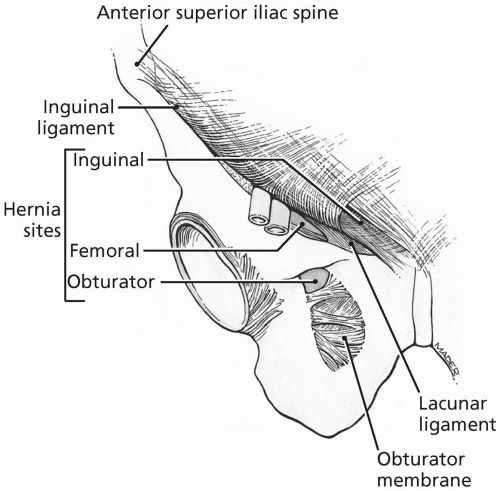

The femoral triangle is situated in the superomedial third of the anterior thigh and is bounded by the inguinal ligament, deep to the inguinal crease, superiorly, the adductor longus muscle medially and the sartorius muscle laterally. The inguinal ligament, the base of the triangle, extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. The triangle appears as a depression inferior to the inguinal ligament when the hip is flexed, abducted, and laterally rotated. The floor of the triangle is formed by portions of the adductor longus, pectineus, and iliopsoas muscles. The hip joint lies deep to the floor of the femoral triangle. The roof is formed by fascia lata and cribriform fascia. The apex of the triangle is the point where the medial border of the sartorius crosses the medial border of the adductor longus.

From lateral to medial, the main contents of the femoral triangle are the femoral nerve (L2-L4) and its branches, the femoral artery and its branches, the femoral vein and its tributaries, including the great saphenous vein, and the femoral sheath. The femoral head lies deep to the femoral artery. The femoral sheath is a funnel-shaped fascial tube that encloses the proximal portions of the femoral vessels and the femoral canal. It does not enclose the femoral nerve. The femoral sheath terminates about 4 cm inferior to the inguinal ligament by becoming continuous with the connective tissue covering the femoral vessels. The great saphenous vein and lymphatic vessels pierce the medial wall of the femoral sheath. This sheath allows the femoral vessels to glide deep to the inguinal ligament during hip flexion.

The femoral sheath is subdivided into three vertical compartments by connective tissue septa. These include a lateral compartment for the femoral artery, an intermediate compartment for the femoral vein, and a medial compartment space called the femoral canal. This latter space allows the femoral vein to expand when there is increased venous return from the lower limb. The femoral canal contains fat, lymphatic vessels, and some deep inguinal lymph nodes. The femoral canal opens into the abdomen at its superior end, the femoral ring. Superficial inguinal

lymph nodes can be palpated in the most medial portion of the triangle.

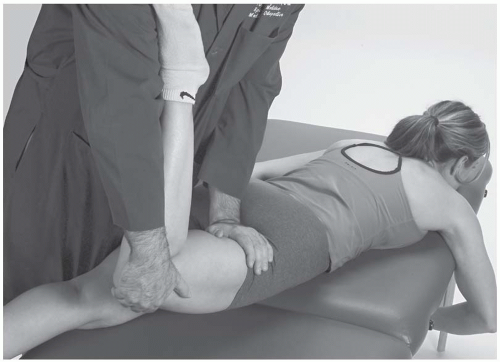

In the region of the greater trochanter is the trochanteric bursa, which protects the posterior and lateral portions of the greater trochanter. This bursa separates the overlying gluteus maximus muscle from the lateral side of the greater trochanter. The gluteus medius muscle attaches to the superolateral portion of the trochanter.

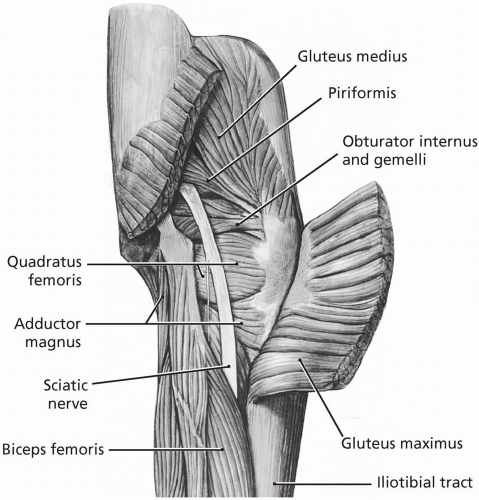

Posteriorly, in the region of the sciatic nerve, the nerve (L4-L5, S1-S3) can be located midway between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity as it emerges through the inferior portion of the greater sciatic foramen, inferior to the piriformis muscle, into the gluteal region (see

Fig. 22.1.7). When the hip is extended the sciatic nerve is covered by the gluteus maximus muscle, which moves out of the way when the hip is flexed, making the nerve accessible to palpation. The ischial bursa separates the gluteus maximus from the ischial tuberosity.

The region of the iliac crest is important because the sartorius and gluteal muscles attach just below it and the cluneal nerves cross over it. These nerves (L1-L3) supply the skin over the iliac crest between the posterior superior iliac spine and the iliac tubercle.

Muscles of the hip and pelvis lie in quadrants based on their position and functions. The anterior quadrant contains the flexor muscles. The most important muscles include iliopsoas, sartorius, and rectus femoris. The iliopsoas muscle is a prime stabilizer of the spinal column and the primary hip flexor. It is the conjoint muscle and tendon of the iliacus and psoas major. This muscle is crucial in several functions and roles:

Crosses L5-S1 and distributes forces from the large range of motion above through to the relatively limited movement of the sacrum.

Distributes forces from below the pelvis cephalad.

Originates at the inferior border of the transverse process of L1-L5 and the anterolateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies of T12-L5 and the intervertebral discs between them.

Anchors the crura of the diaphragm and is involved in respiratory function.

Moves the sacrum in an anterior-posterior fashion.

Acts as a prime mover of the lumbosacral junction, influencing sacral mechanics.

Affects the lumbar curve. Relaxation of the psoas muscle allows the normally present lumbar lordosis to flatten. Stretching of the iliopsoas muscle may alleviate low back discomfort. A home stretching program directed at the iliopsoas may alleviate pain in the low back.

Affects mechanics of gait, respiration, and the sequence of engagement, flexion, descent, and internal rotation of the fetus.

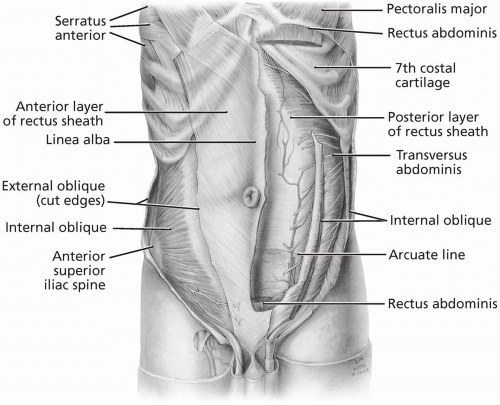

The sartorius flexes, abducts, and medially rotates the hip as well as flexing the knee. The iliopsoas crosses both the hip joint and the knee joint, acting as a flexor of the hip and an extensor of the knee. The iliopsoas is innervated by the anterior primary rami of the L1-L3 spinal nerves. The femoral nerve innervates the sartorius (L2-L3) and rectus femoris (L2-L4) muscles. The abdominal wall consists of the rectus abdominis, external and internal obliquus, and transversalis abdominis muscles (

Fig. 22.1.4). Their function is crucial in the support of the lumbar spine and core stabilization. The abdominal wall inserts into the anterior aspect of the pelvis, and the transversalis aponeurosis blends into the inguinal canal. The conjoint tendon along the rim of the pelvic outlet is a popular location for the injuries often called “sports hernias.” Inguinal hernias are also common sports injuries that can occur in more than one place (

Fig. 22.1.5).

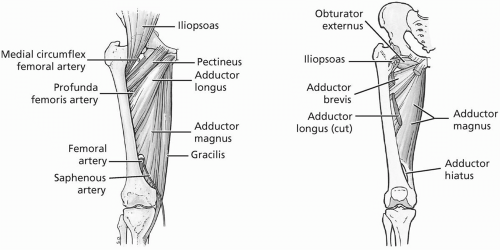

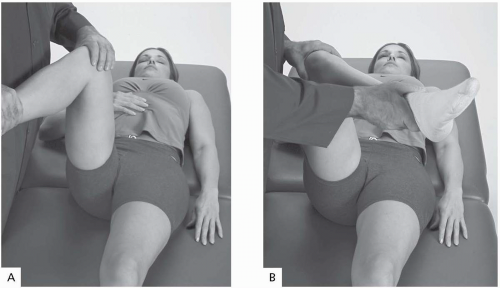

The medial quadrant contains the adductor muscles of the hip (

Fig. 22.1.6). The most important muscles in this quadrant include the gracilis, pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and adductor magnus. The femoral nerve (L2-L3) innervates the pectineus, while the obturator nerve innervates the adductor longus (L2-L4), adductor brevis (L2-L4), adductor magnus (L2-L4), and gracilis (L2-L3).

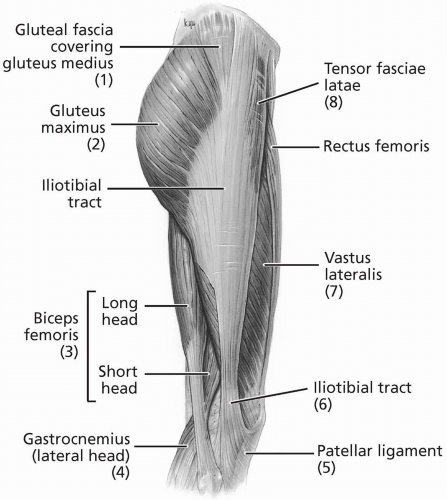

The lateral quadrant contains the abductor muscles of the hip. The most important muscles in this quadrant include the gluteus

medius and minimus (

Fig. 22.1.7). The gluteus medius is the main hip abductor. The superior gluteal nerve (L5, S1) innervates both muscles.

The posterior quadrant contains the extensor muscles of the hip. The most important muscles in this quadrant include the gluteus maximus and hamstring (biceps femoris long

and short heads, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus) muscles. The gluteus maximus is the primary hip extensor and can be located between two imaginary lines drawn between the posterior superior iliac spine and the greater trochanter superiorly and the coccyx and ischial tuberosity inferiorly. The hamstring muscles, except for the short head of the biceps femoris, all attach proximally to the ischial tuberosity deep to the gluteus maximus. The inferior gluteal nerve (L5, S1-S2) innervates the gluteus maximus. The tibial division of the sciatic nerve (L5, S1-S2) innervates the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and long head of the biceps femoris, while the common fibular portion of the sciatic nerve (L5, S1-S2) innervates the short head of the biceps femoris.

REFERENCES

1. Basmajian JV, Slonecker CE. Grant’s method of anatomy, 11th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

2. Clemente CD. Gray’s anatomy of the human body, Amercian 30th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1985.

3. Moore KL, Agur AM. Essential clinical anatomy, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

4. Rosse C, Gaddum-Rosse P. Hollinshead’s textbook of anatomy, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

5. Williams PL, Warwick R, Dyson M, Bannister LH. Gray’s anatomy, British 37th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1989.

6. Woodburne RT, Burkel WE. Essentials of human anatomy, 9th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.