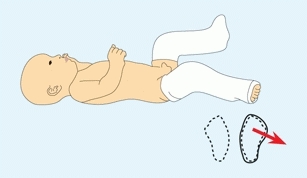

A Fetal foot development The limb bud appears by about 4 weeks of gestation and the foot is well formed by about 7 weeks.

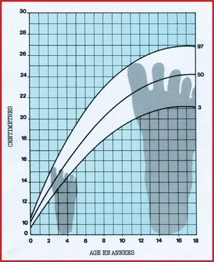

B Foot growth Dimeglio charts show the growth of the foot for girls (left) and boys (right). Note that growth of the foot slows earlier than growth in stature.

Arch Development

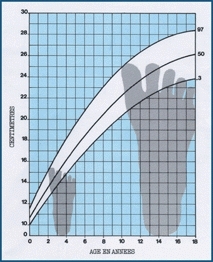

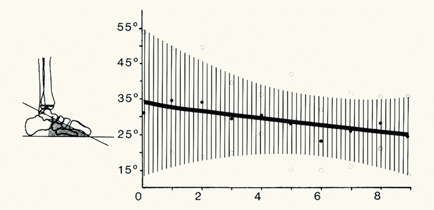

The longitudinal arch of the foot develops with advancing age [C]. The flatness of the infant’s foot is due to a combination of abundant subcutaneous fat and joint laxity common in infants. This joint laxity allows flattening of the arch when the infant stands, and the fatty foot further obscures the longitudinal arch.

C Arch development The longitudinal arch develops with growth in childhood. Note the wide range of normal. Flatfeet fall within the normal range. From Staheli et al. (1987).

Normal Variability

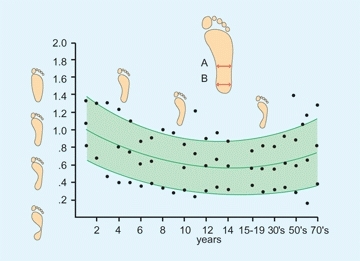

Accessory centers of ossification are common about the foot [A]. Most fuse with the primary center and become part of the parent ossicle. Others remain as separate ossicles, usually attached to the parent bone by cartilage or fibrous tissue. These ossicles are clinically important because they may be confused with a fracture, and they may become painful when the syndesmosis or synchondrosis is disrupted. Such disruptions commonly involve the accessory navicular and an ossicle inferior to the lateral malleolus.

A Common accessory ossification centers about the foot (A) Os trigonum (white arrow), (B) medial malleolar ossicle, (C) lateral malleolar ossicle, (D) accessory navicular (often painful), and (E) os vesalianum. An apophysis may be confused with an accessory ossicle (yellow arrow).

Foot in Systemic Disorders

Evaluation of the foot is a useful aid in diagnosing constitutional disorders. For example, polydactylism is seen in chondroectodermal dysplasia. Dysplastic nails are found in the nail–patella syndrome.

Nomenclature

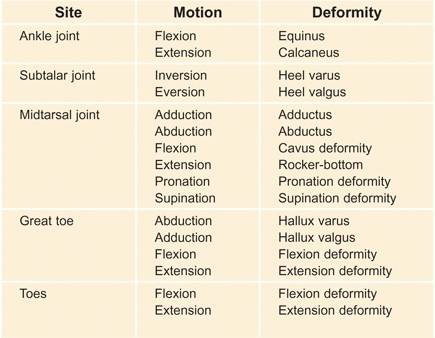

To clarify this discussion, terms describing joint motion versus those describing deformities are defined separately [B]. The anatomical position is considered neutral. Often deformity is designated simply by describing the motion and adding the term deformity behind it. Thus, the subtalar joint fixed in inversion is referred to as an inversion deformity. Note that the description of great toe position is inconsistent with standard terminology. The reference point is the center of the foot rather than the center of the body. Thus, the position of the great toe toward the midline of the body is referred to as abduction.

B Nomenclature for normal joint motion and deformity Joint motion and deformity should be described independently.

Both bones and joints may be deformed. For example, medial deviation of the neck of the talus occurs in clubfeet. This contributes to the adduction deformity. Joint deformity is usually due to stiffness with fixation in a nonfunctional position. Limit the use of the terms varus and valgus to describe deformities.

Evaluation

Family History

Foot shape often runs in families [C]. If the deformity is present in an adult, inquiry about disability may help in managing the child’s problem.

C Familial hallux varus Note the same deformity in the mother’s and daughter’s feet.

Screening Examination

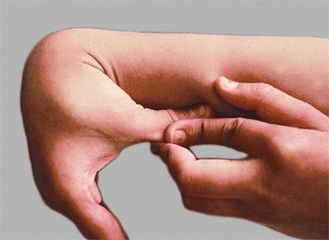

Perform a screening examination. Look at the back for evidence of a spinal dysraphism that may account for a cavus foot. Assess joint laxity [D], as this may be a cause of flexible flatfeet.

D Generalized joint laxity This child’s thumb is easily opposed to the forearm. The child also has a flexible flatfoot.

Foot Examination

The diagnosis of most foot disorders can be made by physical examination. Bones and joints of the foot have little overlying obscuring soft tissue, thus deformity and swelling are easily observed. Furthermore, localization of the point of maximum tenderness (PMT) is readily established.

Observation

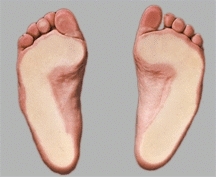

Observe the skin on the sole of the foot for signs of excessive loading [A and B]. Excessive loading that causes calluses is not normal in children. Common sites of excessive loading include the metatarsal heads, the base of the fifth metatarsal, and under the head of the talus. The deformities that cause the calluses are likely to cause pain in adolescence.

A Sole contact area Note the broad even weight distribution on the soles of these normal feet. Child is standing on a glass surface.

B Examine the sole for signs of excessive loading Note the calluses under the metatarsal heads of both feet in this child with congenital toe malformations.

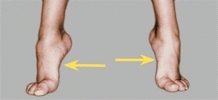

Observe the foot with the child standing. Note the alignment of the heel. Heel valgus is common. Note the height of the longitudinal arch. Next, ask the child to toe stand. A longitudinal arch is established in the child with a flexible flatfoot [C]. With the child seated and the foot unweighted, a longitudinal arch also appears in the child with a flexible flatfoot.

C Flexible flatfeet The longitudinal arch absent on standing (white arrows) appears on toe standing (yellow arrows).

Range of Motion

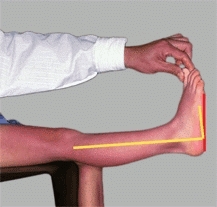

Estimate the range of motion of the toes and the subtalar and ankle joints. Estimate subtalar joint mobility by the range of inversion and eversion motion. Assess ankle motion both with the knee flexed and extended and with the subtalar joint in neutral alignment [D]. Dorsiflexion to at least 20° with the knee flexed and to 10° with the knee extended should be possible.

D Assessing ankle dorsiflexion Right angle (yellow) is neutral position. Assess dorsiflexion (red lines) with the knee extended and flexed to determine site and severity of triceps contractures.

Palpation

By palpation, determine if any tenderness is present. Determining the PMT is especially helpful in the foot because much of the foot is subcutaneous. The PMT is often diagnostic or at least helpful in making decisions regarding imaging.

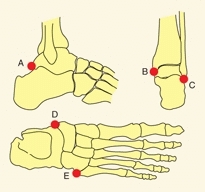

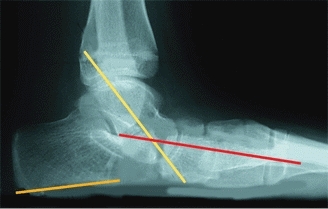

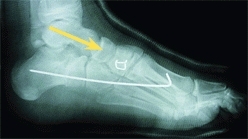

Imaging

Whenever possible, radiographs of the feet should be taken with the child standing [E]. If radiographs are indicated, order AP and lateral projections. If subtalar motion is limited, an oblique view of the foot should be added to rule out a calcaneonavicular coalition. The ankle can be evaluated with AP and lateral radiographs. Order a “mortise” view if a problem such as an osteochondritis dissecans of the talus is suspected. Other special views such as flexion–extension studies may be helpful. Compare the radiographs to published standards for children. The normal range is broad and changes with age [F]. CT scans are useful in evaluating the subtalar joint for evidence of a talocalcaneal coalition. Bone scans are useful in confirming the diagnosis of an osteochondrosis, such as Freiberg disease. The scan will be abnormal before radiographic changes are present. MRI is useful for evaluating tumors.

E Standing radiographs Standing radiographs allow the most consistent evaluation. In the adolescent with a skewfoot deformity, the talar inclination (yellow line), metatarsal axis (red line), and calcaneal pitch (orange line) are readily measured.

F Inclination of the talus by age The shaded area represents two standard deviations above and below the mean (heavy line). Note that the values change with age and that the normal range is very broad. From Vander Wilde et al. (1988).

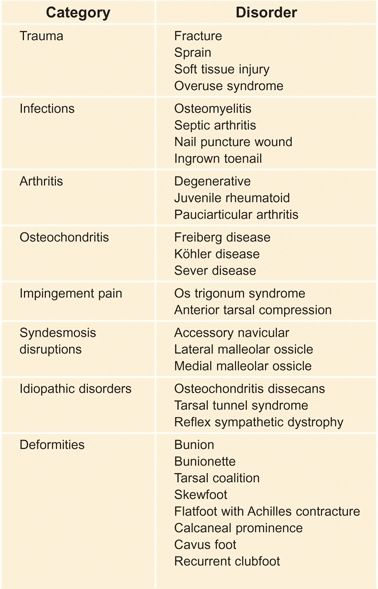

Foot Pain

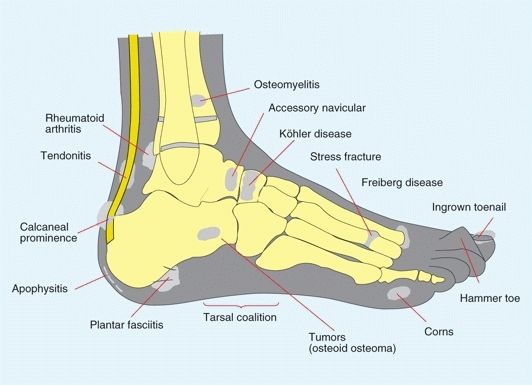

Foot pain in children is common and varied [A and B]. During the first decade of life, foot pain is usually due to traumatic and inflammatory problems, such as injuries and infections, and is seldom due to deformity. During the second decade, foot pain is often secondary to deformity.

A Classification of foot pain The causes of foot pain can be placed in categories for classification and diagnosis.

B Foot pain localization Because the foot is largely subcutaneous, localization of the tenderness will often aid in establishing the diagnosis.

The cause of the foot pain can often be determined by the history and physical examination. Determining the PMT is especially useful about the foot because the structures are subcutaneous and easily examined [C]. This localization often allows a presumptive diagnosis.

C Point of maximum tenderness The ankle is swollen and tenderness is present just anterior to the distal fibula, typical of a sprain.

Trauma

Stress–occult fractures

Fractures without trauma history are not uncommon in infants and young children. They may be considered as part of the toddler fracture spectrum. Fractures of the cuboid, calcaneus, and metatarsal bones can be best identified by bone scans.

Tendonitis–fasciitis

Repetitive microtrauma is a common source of heel pain in children. This is most common about the os calcis either at the attachment of the heel-cord or the plantar fascia.

Infections

Infections of the foot are relatively common. Septic arthritis commonly affects the ankle and occasionally other joints of the foot. Osteomyelitis may occur in the calcaneus and other tarsal bones. Infection may be hematogenous or iatrogenic (heel sticks for blood sampling) or result from penetrating injuries.

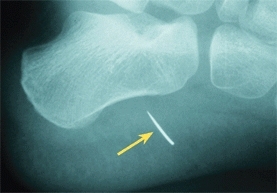

Nail puncture wounds

Nail puncture wounds are common injuries [A and B, next page] that may be complicated by osteomyelitis [C, next page]. About 5% of nail penetrations become infected, but less than 1% develop osteomyelitis. Puncture wounds under the metatarsal are more likely to be caused by Pseudomonas septic arthritis. Infections in the heel are commonly from Staphylococcus or Streptococcus.

Initial management

Examine the foot and remove any protruding foreign material. Probing the wound will be unpleasant and unrewarding. Update tetanus immunization. Inform the family about the risk of infection and the need to return if signs of infection occur. Usually infections will show signs several days after the injury and include increasing discomfort, swelling on the dorsum of the foot, and fever.

Management of infection

Culture the wound and obtain an AP radiograph of the foot to serve as a baseline. The time of onset of signs of an infection suggests the infecting agent. If the interval between penetration and infection is 1 day, the organism is likely to be Streptococcus. If the interval is 3–4 days, Staphylococcus is most likely, and if a week, Pseudomonas. Children with Pseudomonas infections were usually wearing shoes at the time of the penetration. Operative debridement and drainage are indicated in all Pseudomonas infections. Drainage is also indicated in all infections that fail to improve promptly with antibiotic treatment.

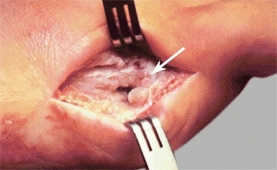

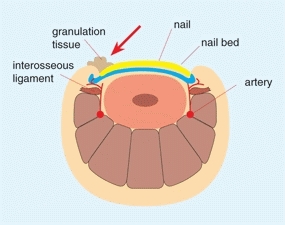

Ingrown toenails

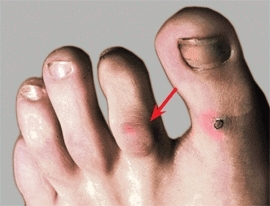

Ingrown toenails [D] are common infections resulting from a combination of anatomical predisposition, improper nail trimming, and trauma. Injury or constricting shoes or stockings may initiate the infection. In children prone to developing this problem, the nail is abnormal, often showing a greater lateral curvature of the nail into the nailbed.

A Nail puncture wound Erythema and a puncture wound (arrow) show the site of nail entry. Swelling is most prominent on the dorsum of the foot.

B Needle penetration into heel Radiograph (left) shows broken needle. Photograph (right) shows site of entry of needle and surrounding inflammation.

C Chronic osteomyelitis A nail puncture wound through a shoe was followed by this infection that involved the bone and joint (white arrow). The joint was destroyed. Chronic osteomyelitis of the first metatarsal (yellow arrow) is evident in the radiograph.

D Ingrown toenails Inflamed soft tissue around the ingrown nail (red arrow). Photograph shows typical clinical appearance (white arrow).

Management of early infections

Choose treatment based on the severity of the inflammation. Mild irritation requires only proper trimming of the nail and properly fitting shoes. Nails should be trimmed at right angles. Avoid trimming the nail to create a convex end. Instruct the family to trim the nail to create a concave end that leaves the nail edges extending beyond the skin to prevent recurrent ingrowth. Elevate the soft tissue from the nail plate with a wisp of cotton. Avoid forceful packing. Repeat this several times if necessary to lift the inflamed soft tissue from the nail plate. If inflammation is more severe, rest, elevation, protection from injury, soaking to clean and promote drainage, and antibiotics may be necessary.

Management of late infections

Persistent severe lesions require operative management. The hypertrophic chronic granulation tissue is excised, and removal of the lateral portion of the nail together with a portion of the nail matrix may be necessary to prevent recurrence.

Pauciarticular Arthritis

Pauciarticular arthritis may present with foot pain in the infant or young child. A limp, limited ankle or subtalar motion, and swelling for more than 6 weeks’ duration suggests this diagnosis [E]. In contrast with septic arthritis, pauciarticular arthritis looks like it should hurt more than the child reports. The pain is often minimal.

E Arthritis of the ankle This child has pauciarticular arthritis affecting the ankle.

Osteochondritis

Köhler disease

Tarsal navicular osteochondritis, also known as Köhler disease, is an avascular necrosis most common in boys between 3 and 10 years of age [A]. It also occurs uncommonly in girls 2 to 4 years of age. The disease produces inflammation, localized tenderness, pain, and a limp. Radiographic changes depend on the stage of the disease. The navicular first shows collapse and increased density. Patchy deossification follows. Finally, the navicular is reconstituted. Because healing occurs spontaneously, only symptomatic treatment is necessary. If pain is a significant problem, immobilize the foot in a short-leg walking cast for 6–8 weeks to reduce inflammation and provide relief of pain. Long-term follow-up studies show no residual disability.

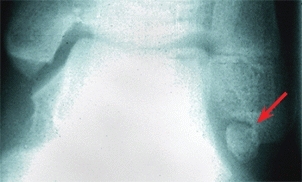

A Köhler disease in a 5-year-old boy The tarsal navicular of the left foot is sclerotic (arrow) and the site of tenderness.

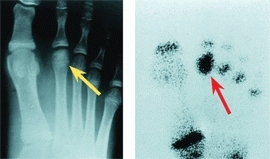

Freiberg disease

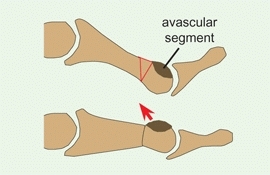

Metatarsal head osteochondritis, also known as Freiberg disease or infraction, is an idiopathic segmental avascular necrosis of the head of a metatarsal. It most commonly occurs in adolescent girls, 13–18 years, and involves the second metatarsal. Pain and localized tenderness [B] are common. If the patient is seen early, a bone scan will show increased uptake and establish the diagnosis. Later, radiographs will show irregularity of the articular surface, sclerosis, fragmentation, and finally reconstitution. Residual overgrowth and articular irregularity may lead to degenerative changes and persistent pain. Treat with rest and immobilization to reduce inflammation. An orthosis to unweight the involved metatarsal head, sole stiffeners to reduce motion of the joint, and even a short-leg walking cast may be useful. For severe persisting pain, operative correction may be necessary. Options include joint debridement, excisional arthroplasty (proximal phalanx), interposition arthroplasty using the tendon of the extensor digitorum longus, and dorsiflexion osteotomy [C] of the metatarsal (often the best choice).

B Freiberg disease Tenderness over the head of the second metatarsal is usually present in Freiberg disease. Minimal changes are present in the radiograph (yellow arrow), and the bone scan shows increased uptake over the second metatarsal head (red arrow). The photograph shows the point of maximum tenderness (green arrow).

C Metatarsal osteotomy for pain due to Freiberg deformity This procedure moves the avascular segment of the metatarsal head away from the joint.

Sever disease

or calcaneal apophyseal osteochondrosis is commonly diagnosed by heel pain and radiographic features of fragmentation and sclerosis of the calcaneal apophysis. These radiographic changes occur commonly in asymptomatic children [D]. This condition resolves with time. Most heel pain in children is due to inflammation of the attachment of the plantar fascia or heel-cord.

D Calcaneal apophysis In the normal child, this apophysis often shows sclerosis and fragmentation.

Impingement Pain

Os trigonum syndrome

Compression of the ossicle in dancers often causes foot pain.

Mid tarsal impingement

Mid foot pain is sometimes due to compression of articular margins often secondary to tarsal coalitions or heel-cord contracture [E].

E Impingement This is talar beaking associated with a tight heel-cord and impingement.

Syndesmosis Disruption

Disruption of the syndesmosis between the primary ossicle and a secondary center of ossification (accessory ossicle) is a common cause of pain in the feet of children and teenagers. This disruption is the equivalent of a stress injury of the cartilaginous or fibrous attachment. It becomes painful and tender [A] unless healing is complete. The condition commonly recurs.

A Accessory navicular The accessory navicular is located on the medial aspect of the foot (arrows). It often produces a prominence and is sometimes painful.

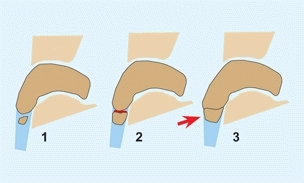

Accessory navicular

is an accessory ossification center on the medial side of the tarsal navicular that occurs in about 10% of the population and remains as a separate ossification center in about 2%. They are classified into three types [B]. Type 1 is seldom symptomatic. Type 2 is most likely to have pain from disruption of the synchondrosis. Disruptions are common during late childhood and adolescence and are probably due to repetitive trauma. This disruption causes pain and localized tenderness. Type 3 causes a prominence that, if large, may cause irritation of the overlying skin.

B Classification of accessory navicular Type 2 with disruption of the synchondrosis (red arc) and type 3 producing a prominence (arrow).

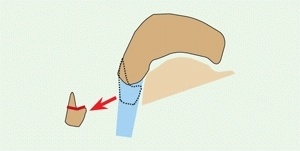

Manage pain with a short-leg cast or splint. If the pain persists, excision of the accessory navicular may be necessary. Simply excise the ossicle and a portion of the elongated primary navicular through a longitudinal split in the fibers of the posterior tibial tendon [C]. Avoid the more extensive Kidner procedure, which requires rerouting the tendon and does not improve the outcome.

C Excision of accessory navicular The painful type 2 ossicle is removed, leaving the tendinous posterior tibial tendon attached to the navicular (arrow).

Malleolar ossicles

Ossification centers occur below the medial and lateral malleoli. Persisting ossicles under the lateral malleolus are most likely to be painful [D]. Manage first by cast immobilization. Rarely, excision or stabilization by internal fixation is necessary.

D Lateral malleolar ossicle This ossicle was painful, not improved by casting, and eventually required fusion with screw fixation.

Idiopathic Disorders

Tarsal tunnel syndrome

Foot pain, Tinel’s sign over tarsal tunnel, dysesthesias, and delayed nerve condition suggest this diagnosis. This syndrome differs in children. Typically, the child is female, walks with the foot in varus, may elect to use crutches, and often requires operative release.

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

This syndrome usually affects the lower limb in girls [E]. Consider this diagnosis when the foot is swollen, stiff, cool, and generally painful. A history of injury is common. Pain assessment by the child is exaggerated and does not match the history or physical findings. See Chapter 3 for management.

E Reflex sympathetic dystrophy The varus deformity of the left foot is due to reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Foot Deformities

Foot deformities may cause pain due to pressure over bony prominences [F] or to altered mechanics of the foot. Pain from deformity is usually not difficult to recognize.

F Foot deformities in a child with spina bifida Prominence of the head of the talus caused skin breakdown in the foot with diminished sensation.

Toe Deformities

Generalized Disorders

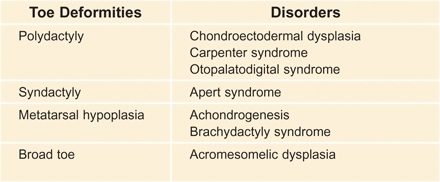

If a toe deformity is found, carefully examine the hands and feet of the child and of the parents. These deformities are sometimes manifestations of a generalized disorder [A].

A Syndromes associated with toe deformities

Cleft Foot Deformity

This rare deformity is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait, is usually bilateral, and often involves the hands and feet [B]. A noninherited form is less common and is often unilateral. If it causes shoe-fitting problems, correct in late infancy or childhood by osteotomy and soft tissue approximation.

B Cleft foot deformity These deformities are present in both the father and the son. The major problems are difficulties with shoe fitting and the unusual appearance.

Microdactyly

Small toes are often found in Streeter dysplasia and may be secondary to intrauterine hypotension, causing insufficient circulation to the toes [C]. No treatment is required.

C Microdactyly

Syndactyly

Syndactyly is most common between the second and third toes, is usually bilateral and often familial. Fusion of the toes produces no functional disability and treatment is unnecessary. Look for some underlying problem if it involves more than two locations.

Polydactyly

Polydactyly or supernumerary digits are common [D]. They are most common in girls and in blacks and are sometimes inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Most involve the little toe and duplication of the proximal phalanx with a block metatarsal or wide metatarsal head. Excise the extra digit late in the first year when the foot is large enough to make excision simple and before the infant is aware of the problem. Plan the procedure to minimize the scar, establish a normal foot contour, and avoid disturbing growth. Central duplications often cause permanent widening of the foot. Poor results are more likely for great toe duplications with persistent hallux varus and complex deformities [E and F].

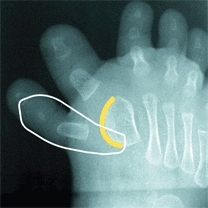

D Excision of bifid great toe Half of the toe is removed. Excision of complex polydactyly is sometimes difficult.

E Polydactyly Polydactyly causes a cosmetic and shoe-fitting problem. Excision of the accessory toe is appropriate late in the first year.

F Bracket epiphysis Toe deformities may be complex. In this case, the metatarsal epiphysis (yellow arc) is continuous for both toes. Excise the accessory digit and the adjacent portion of the growth plate.

Curly Toes

Curly toes [A] are common in infancy and produce flexion and rotational deformities of the lesser toes. The deformity nearly always resolves spontaneously. Rarely, flexor tendonectomy is required for those that persist beyond age 4 years.

A Curly toes This deformity may involve one or more toes and usually resolves spontaneously.

Claw Toes

Claw toes are usually associated with a cavus foot and are often secondary to a neurologic problem. Correction is usually part of the management of the cavus foot complex.

Hammer Toes

Hammer toes are secondary to a fixed flexion deformity of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint [B]. The distal joint may be fixed or flexible. The condition is often bilateral, familial, and most commonly involves the second toes and less frequently the third and fourth. Operative correction is indicated in adolescence if the deformity produces pain or shoe-fitting problems. Correct by releasing the flexor tendons and fusing the PIP joint.

B Hammer toe The fixed flexion deformity of the PIP joint of the second toe causes a callus (arrow) to form over the toe.

Mallet Toes

Mallet toes are due to a fixed flexion deformity of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. These deformities are uncommon.

Overlapping Toes

Overlapping toes are common. Overlapping of the second, third, and fourth toes usually resolves with time. Overlapping of the fifth toe is more likely to be permanent [C] and cause a problem with shoe fitting. Overlapping of the fifth toe is often bilateral and familial. If overlapping becomes fixed, persists, and causes shoe-fitting problems, operative correction is appropriate. Correct with the Butler soft tissue alignment procedure [D]. This involves a double racket-handle incision, lengthening of the extensor tendon, releasing the joint contracture, and skin repair with the toe translated to a more plantar and lateral position.

C Overlapping toe This overlapping fifth toe persisted and required operative correction.

D Operative correction of overlapping toe Through a bucket handle incision (white line) lengthen the extensor tendon and capsule, correct the deformity, and close the skin, maintaining the correction (red line).

Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy [E] is seen in children with Proteus syndrome, neurofibromatosis, or vascular malformation, or it can occur as an isolated deformity. Most show abnormal accumulation of adipose tissue, and some show endoneural and perineural fibrosis and focal neural and vascular proliferation. Management is difficult. Epiphysiodesis, debulking, ray resection, and through-joint amputations are often necessary. Recurrence is frequent, and several procedures are often required during childhood to facilitate shoe fitting.

E Hypertrophy Overgrowth may cause severe shoe-fitting problems and require resection, epiphysiodesis, or amputation.

Forefoot Adductus

Metatarsus Adductus and Varus

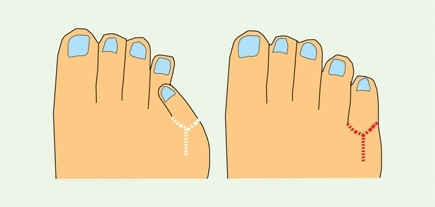

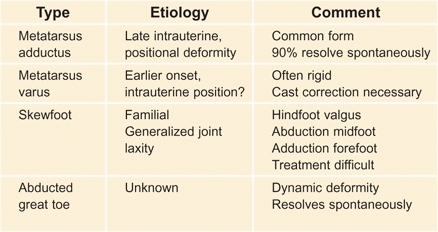

Adductus of the forefoot is the most common foot deformity. It is characterized by a convexity to the lateral aspect of the foot [A] or a dynamic abduction of the great toe [B]. The deformities fall into four categories [C].

A Metatarsus adductus A convexity of the lateral border of the foot (red line) is the most consistent feature of this deformity.

B Great toe abduction This is a dynamic deformity that resolves with time.

C Types of forefoot adductus and varus deformities The differential diagnosis of metatarsus adductus should include the rigid, nonresolving form, and the skewfoot.

Metatarsus adductus

is a common intrauterine positional deformity. Because it is associated with hip dysplasia in 2% of cases, a careful hip evaluation is essential. Metatarsus adductus is common, flexible, benign, and resolves spontaneously.

Metatarsus varus

is an uncommon rigid deformity that often persists and requires cast correction. Metatarsus varus does not produce disability and does not cause bunions, but it does produce cosmetic and occasionally shoe-fitting problems.

Skewfoot

is discussed on the next page.

Great toe abduction

is a dynamic deformity due to overactivity of the great toe abductor. It is sometimes called a “searching toe.” The condition improves spontaneously. No treatment is required.

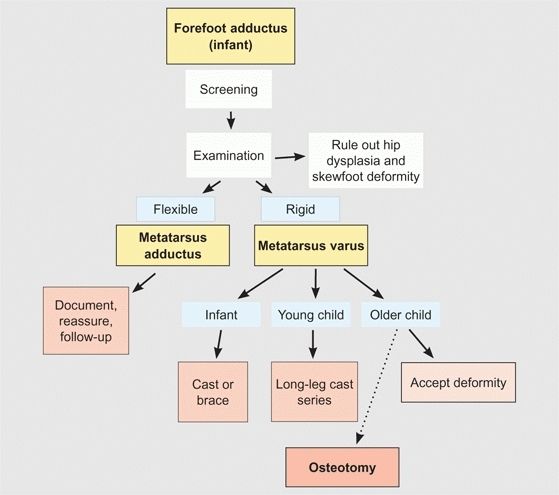

Management

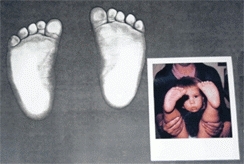

Evaluate by performing a screening examination, test for stiffness, and consider the child’s age [D]. Manage metatarsus adductus by documentation and observation [E].

D Steps in managing forefoot adductus

E Imaging the adducted foot The infant’s foot shape is recorded on a copy machine. The printout from the copy machine is compared to a photograph.

Manage metatarsus varus by serial casting [A and B] or bracing. Long-leg bracing is useful in the toddler. Serial casting is most effective. The deformity yields much more rapidly when the cast is extended above the flexed knee.

A Long-leg cast for metatarsus varus This treatment of metatarsus varus is most effective, as the flexed knee provides control of tibial rotation. Using the thigh portion of the cast as a point of fixation (yellow arrow), the foot is laterally rotated (green arrow) and abducted (red arrow) to achieve the most effective correction.

B Cast treatment of metatarsus varus This child with a persisting stiff deformity was corrected using these long-leg casts. The knee is flexed to about 30° to control rotation. The foot is abducted in the casts. The casts are changed every 2–3 weeks until correction is completed.

The following technique is useful to about age 5 years. Apply a short-leg cast first. As the cast sets, mold the forefoot into abduction and the hindfoot in slight varus-inversion. Finally, while holding the short-leg cast in neutral rotation and with the knee flexed about 30°, extend the cast to include the thigh. This long-leg cast allows both walking and effective correction.

In the older child, it may be best to accept the deformity, as it does not cause disability. If operative correction is selected, correct by opening wedge cuneiform and closing wedge cuboid osteotomies. Avoid attempting correction by capsulotomy or metatarsal osteotomies, as early and late complications are frequent.

Skewfoot

Skewfoot, Z-foot, and serpentine foot are all terms given to a spectrum of complex deformities. This deformity includes hindfoot plantarflexion, midfoot abduction, and forefoot adduction [D]. A tight heel-cord is usually present in symptomatic cases. Skewfeet are seen in children with myelodysplasia; they are sometimes familial but are usually isolated deformities. There is a spectrum of severity. Some practitioners describe overcorrected clubfeet as skewfeet. Idiopathic skewfeet may persist and cause disability in adolescence and adult life.

D Skewfoot deformity Note the forefoot adduction in the photograph, the plantar flexed talus (red arrow), and the Z alignment (white lines).

Manage idiopathic skewfeet in young children by initial serial casting, correcting the forefoot adductus while carefully avoiding any eversion stress on the hindfoot. Document the effect of growth on the deformity. Most will persist. Plan correction in late childhood with heel-cord lengthening and osteotomies. Lengthen the calcaneus and medial cuneiform by opening wedge osteotomies [C].

C Sequence of correction of skewfoot Calcaneal and cuneiform osteotomies and a heel-cord lengthening were performed. Note the changes in talar alignment between the preoperative (red arrows) and postoperative (yellow arrows) radiographs.

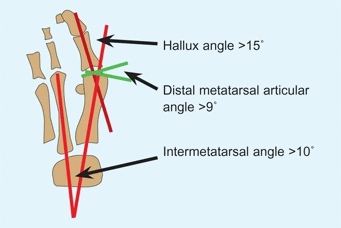

Bunions

A bunion is a prominence of the head of the first metatarsal [A]. It is most common in girls. In children, it is usually due to metatarsus primus varus, a developmental deformity characterized by an increased intermetatarsal angle [B] that exceeds about 9° between the first two rays. Over time, the medial cuneiform becomes more trapezoid in shape and the metatarsal phalangeal joint subluxated. Hallux valgus is a secondary deformity aggravated by wearing shoes, as the great toe must be positioned in valgus to fit within a shoe. The normal hallux valgus angle is <15°. The combination of primary and secondary deformities causes the typical adolescent bunion [C].

A Measurements for bunion assessment These values are usually present in bunion deformity.

B Moderate bunion deformities The bunion is a prominence over the head of the first metatarsal. The left bunion (arrow) is most prominent here, and both are relatively moderate. Usually no active treatment is required for bunions of this severity.

C Metatarsus primus varus An increased intermetatarsal angle (between red lines) is present in metatarsus primus varus. The hallux valgus is a secondary deformity.

Bunions are often familial [D] and may occur in children with neuromuscular disorders [E]. Other factors may include pronation of the forefoot, joint laxity, and pointed shoes. Bunions are uncommon in barefoot populations.

D Familial bunions Both mother and daughter have bunions.

E Severe hallux valgus in cerebral palsy Note the absence of metatarsus primus varus and any prominence of the metatarsal head.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree