Flexor Hallucis Longus Transfer for Achilles Tendinosis

Bryan D. Den Hartog Jr.

DEFINITION

Insertional and midsubstance Achilles tendinosis is a painful degenerative process that arises due to mechanical and vascular factors and affects the paratenon and collagen fibers.

It is most commonly seen in patients in their mid-40s and older.

ANATOMY

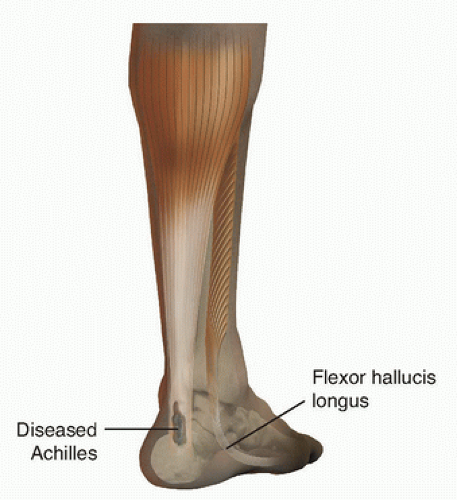

The Achilles tendon, the largest tendon in the body, connects the gastrocsoleus complex to the calcaneus (FIG 1).

It is covered by a paratenon without a definite tendon sheath.

The blood supply of the tendon arises distally from calcaneal arterioles and proximally from intramuscular branches. There is a relatively hypovascular, or watershed, area 2 to 4 cm proximal to the tendon insertion.

PATHOGENESIS

Mechanical and vascular factors contribute to the development of tendinosis. The process begins with mechanical pressure on the insertion of the Achilles tendon from internal factors, a Haglund deformity, or external factors, such as a firm heel counter. Retrocalcaneal bursitis develops initially without Achilles tendon involvement. Increasing prominence of the posterolateral calcaneal tuberosity or hindfoot malalignment (ie, varus heel) can cause tendon collagen fiber injury and further inflammation of the retrocalcaneal bursa.

Progressive thickening of the retrocalcaneal bursa and peritendinous tissue increases mechanical pressure on the tendon, impeding blood flow, and hampering the normal repair process, leading to a thickened, degenerative tendon.

With dysvascular changes associated with aging, the tendon becomes increasingly thick and painful. Radiographs at this point may show a spur or calcification at the Achilles insertion.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of the pathologic process most likely is a continuum that begins with retrocalcaneal bursitis and ends in chronic Achilles tendinosis.

Patient activity becomes more restricted due to increased pain and weakness.

Age-dependent changes in collagen quality and decreased vascularity contribute to the development of tendinosis.

As the degenerative process becomes chronic, the tendon becomes mechanically deficient and more susceptible to rupture.

Symptoms become unremitting as the disease progresses.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Achilles tendinosis causes pain and swelling of the diseased segment of tendon.

Pain increases with physical activity and with direct pressure on the affected tendon.

Patients with seronegative arthropathies, spondyloarthropathies, hypercholesterolemia, sarcoidosis, and renal transplant have an increased incidence of Achilles tendinopathy.

The patient should be assessed for hyperpronation or heel varus deformities, which can cause eccentric Achilles tendon loading. If either is present, an orthosis to keep the hindfoot in neutral may be necessary.

Ankle dorsiflexion is measured with the knee flexed and extended to assess for gastrocnemius or Achilles tendon tightness. If excessive tightness is present, a gastrocnemius recession should be considered along with the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) transfer.

With the patient prone on the examining table, the Achilles tendon is palpated to localize the area of thickening and tenderness (either insertional or noninsertional). Assess the size of the calcaneal tuberosity; if it is enlarged, excision of this prominence should be considered to reduce mechanical pressure on the diseased Achilles tendon.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs are useful in evaluating the extent of tendon calcification and presence of a Haglund deformity (FIG 2A).

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning is not essential for preoperative planning, it can be beneficial in estimating the amount of degenerative tendon to be excised (FIG 2B,C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Haglund deformity

Os trigonum

Retrocalcaneal bursitis

Peritendinitis

Seronegative spondyloarthropathy

Insertional tendinopathy

Achilles tendinosis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonsurgical treatment of insertional or noninsertional Achilles tendinosis includes rest, immobilization, and rehabilitation.

Immobilization can include casting, a cast brace, and a custom-molded ankle-foot orthosis (AFO).

Structural abnormalities such as heel varus are addressed with wedges or orthotics, or both.

Training regimens are modified to reduce stress on the affected tendon.

Physical therapy for heavy load eccentric strengthening exercises has been found to be effective for Achilles tendinopathy and may be superior to conventional treatment regimens and comparable to open débridement of the tendon.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is performed only on those patients who have intractable pain and impaired function or those who have failed previous tendon débridement or Haglund resection alone.

Most people in this patient group have a chronic Achilles tendon deficiency and are sedentary, overweight, and have radiographic or MRI evidence of a thickened, calcific

Achilles insertion.

Most treatments that have been described focus on removing mechanical pressure from the diseased tendon (eg, excising the posterosuperior calcaneal tuberosity), débridement of the diseased tendon, or augmentation of the remaining, débrided tendon (ie, FHL, peroneus brevis, plantaris).

The bulk of surgical treatment is discussed in the following sections and in the Techniques section.

Preoperative Planning

The extent and location of diseased tendon must be identified. The area of tendon degeneration most often is the distal 2 to 4 cm. The degeneration also may be isolated at the midsubstance.

The patient must understand preoperatively that the time to maximum improvement could be prolonged (average 8.2 months).

If the surgeon wants to loop the transferred FHL through the calcaneus at the time of the transfer and more tendon length consequently will be needed, the FHL should be harvested from the midmost at Henry knot and pulled out the posterior incision.

Positioning

The patient is placed prone on the operating table with a soft bump anterior to the ankle (FIG 3).

Approach

Various incisions have been used to approach the diseased tendon.

Incisions that have been recommended include central splitting, medial and/or lateral longitudinal pretentious, or medial with a transverse L-shaped extension distally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree