Firearm Injury Prevention

Douglas J. Wiebe

Edmund M. Weisberg

Reducing the overall level of violent acts committed in our society is a necessary goal. Violence committed with firearms specifically is a priority issue because gunshot wounds are more lethal than trauma inflicted using other weapons. In addition to being highly lethal, firearm violence has devastating effects on victims’ families and communities, places heavy demands on trauma centers and health care systems, and creates serious physical and mental challenges for survivors.

The surgical management of gunshot trauma is of paramount importance, making the difference between life and death for those who have been shot. However, the trauma community does not bear the burden of firearm injury prevention itself. Far from it, in fact. Trauma surgery represents only one of the multiple points at which elements of the shooting event and its aftermath can be intervened upon in an attempt to achieve firearm injury prevention. Firearm injury prevention is a comprehensive concept, and is defined here as the public health goal of preventing shootings from occurring, as well as minimizing the likelihood that negative outcomes will result when shootings occur. These outcomes include mortality; physical, mental, and emotional morbidity; and costs to the medical system, as well as the impact on families, communities, and society.

This chapter describes a framework for firearm injury prevention. The framework follows the public health approach, which is interdisciplinary and science based.1 This approach draws upon knowledge from many disciplines including medicine, epidemiology, sociology, psychology, criminology, education, engineering, and economics. The combined contributions of each discipline have allowed the field of public health to be innovative and responsive to a wide range of diseases, illnesses, and injuries. As one example, the ability of the field to build knowledge of risk and subsequently reduce motor vehicle crash-related fatalities despite an increase in miles driven is cited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the injury prevention successes of the 20th century.2 With the focus here being on firearm injury prevention, this chapter provides a conceptual model for the shooting event, its precursors, and its aftermath, and presents a tool for identifying opportunities for prevention.

MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM

Gunshot wound injury is the second most common trauma mechanism treated at United States trauma centers, surpassed only by motor vehicle crash-related injuries, and is the second leading cause of death in the United States in the 15- to 34-year-old age-group.3 Moreover, it is the leading cause of violence-related injury deaths in all age-groups up to the age of 34. According to the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) 2006 annual report (on data from 2000 to 2005), 15% of cases of gunshot wound injury result in death after arrival at the hospital or trauma center, which is the highest percentage for any type of penetrating injury. During that period, 60,377 gunshot wound patients were treated at trauma centers and for survivors the average length of hospital stay was 6.5 days.

The average medical cost of gunshot injuries in 1998 was an estimated $16,500 per case, with average costs of $22,400 for unintentional gunshot injuries, $18,400 for assault-related injuries, and $5,400 for self-directed shootings.4 Significantly, a substantial portion of the costs

of treating gunshot victims is shouldered by government programs and less so by private insurers; in both cases, though, higher costs are transferred to the general public in terms of higher taxes and higher insurance premiums.4

of treating gunshot victims is shouldered by government programs and less so by private insurers; in both cases, though, higher costs are transferred to the general public in terms of higher taxes and higher insurance premiums.4

Opportunity costs in terms of disability and lost productivity also create a significant impact. For Americans, firearm injuries in 2000 accounted for an estimated $35.2 billion in total lifetime productivity losses.5 Considered in terms of life expectancy, firearm violence shortens the life of an average American by 104 days (151 days for white males, 362 days for black males).6 Using a more expansive definition that also considers societal burdens such as security systems in schools and subsidizing urban trauma centers, Cook and Ludwig estimated that $100 billion is a more accurate assessment of the annual cost of gun violence in the United States.4 Regardless of how narrowly or broadly we may define or identify the costs of gun violence, such violence exerts a considerable burden on individual victims, their families, and society at large. This public health problem is not confined to the United States, we should note, and in fact is identified as a global health priority by the World Health Organization.4,7 For many reasons, then, it is a priority to consider how firearm violence can be prevented.

THE SHOOTING EVENT: INJURY PRECURSORS, INJURY EVENT, AND INJURY CONSEQUENCES

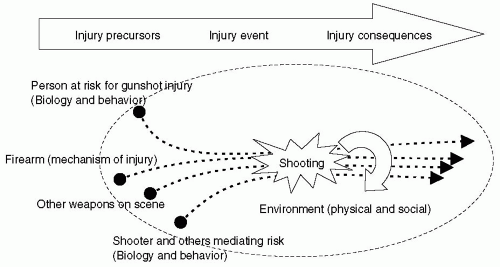

The gunshot injury event—the moment the firearm is discharged—provides us with a focal point from which to consider the event more broadly, including the circumstances that led up to the shooting, and the aftermath of the shooting. This notion of the shooting event has been diagramed by Cheney et al. (see Fig. 1)8 and used to promote interdisciplinary collaboration for the study and prevention of firearm injury. It has been used successfully in broader applications to all injury categories (see Chapter 11).

Figure 1 A conceptual model for interpersonal assault, unintentional, and self-directed gunshot injury. |

The star in the center of the diagram, the focal point, represents the gunshot injury event. The issue that is key to appreciate here is that the gunshot injury event represents only one distinct moment, whereas the chronologic trajectory of events in the life of the gunshot injury victim includes the sequence of precursors as well as consequences. The firearm injury event can be thought to have occurred as a result of the culmination of preceding events that converged at the focal point. The routine activities theory of criminology, for example, conveys this notion well, and explains that for a gunshot injury to occur, there must be a convergence in time and space of three factors: a motivated perpetrator, a suitable target, and the lack of a capable guardian.9,10 Also depicted in Fig. 1 is the fact that the firearm injury event is followed by ramifications for the victim and for others as well, including the victim’s family, the community, the health care system, and society.

Having framed gunshot injury as a public health problem that consists of these three periods—the injury precursors, the injury event, and the injury consequences—we can overlay this model with the concepts of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, respectively. As we shall see more concretely in the subsequent text, each stage refers to a way of identifying strategies to address the problem of firearm injury toward the goal of prevention. Primary prevention activities are those that are designed to prevent instances of an illness, disease, or injury in a population and thereby to reduce, as much as possible, the risk of new cases arising. Therefore, primary prevention activities apply to the injury precursor phase. Secondary prevention activities are those designed to reduce the progress of a disease or injury and occur during the natural history of the disease or injury. Therefore, secondary prevention activities apply to the injury event phase itself—the moment of firearm discharge and the moment of penetrating trauma. Tertiary prevention activities are those designed to limit death and disability from disease and injury, and therefore apply to the injury consequences phase of Fig. 1. In considering that the realm of options available for our work toward the goal of firearm

injury prevention includes strategies of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, we start to frame this problem as one that can be approached in a deliberate and methodical manner. As a result, we can start to view firearm violence as a public health problem that is not intractable, but rather as one with aspects that can be targeted for prevention. The ways in which firearm violence can be targeted become even more concrete by proceeding one step further and considering the Haddon matrix.

injury prevention includes strategies of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, we start to frame this problem as one that can be approached in a deliberate and methodical manner. As a result, we can start to view firearm violence as a public health problem that is not intractable, but rather as one with aspects that can be targeted for prevention. The ways in which firearm violence can be targeted become even more concrete by proceeding one step further and considering the Haddon matrix.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree