Femur Fractures: Antegrade Intramedullary Nailing

Christopher G. Finkemeier

Rafael Neiman

Frederick Tonnos

INTRODUCTION

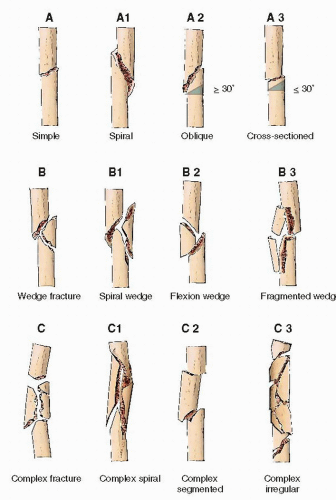

Diaphyseal femur fractures are classified according to the AO/OTA classification (Fig. 22.1). The diaphysis is defined as the area remaining when subtracting the areas formed by a box around the proximal and distal metaphyseal areas of the femur (1). Intramedullary nailing is the most common form of diaphyseal femur fracture fixation performed in the United States. The modern pioneer of nailing was Gerhard Kuntscher, who developed this technique in 1939 and performed it regularly in the 1940s (2). Since that time, many steps in the evolution of the technique have occurred, and nail design continues to evolve. Nevertheless, controversies remain regarding patient position, direction of nailing (retrograde vs. antegrade), nail design, the role of reaming, and the ideal starting point. Most authors recommend static cross-locking of the nail as studies have shown that this does not inhibit fracture healing (3). Intramedullary nailing using a piriformis fossa starting point has been the classic approach to femoral nailing. Due to its difficulty in the supine position, many surgeons are now using a trochanteric starting because it is easier in the supine position. Today there are implants specifically designed for trochanteric entry that accommodate the complex proximal femoral osseous anatomy (4). There are no significant differences in outcome between trochanteric and piriformis starting points (5,6).

Intramedullary reaming has both advantages and disadvantages in a patient with a femur fracture. Reaming allows the surgeon to “sound” the canal, which allows a better assessment of nail diameter. However, the main reason to ream a femur is to allow larger diameter implants, which decreases hardware failure and improves union rates (2,7). An unproven but theoretically attractive advantage of reaming is to deposit finely morselized autogenous bone graft at the fracture site. The disadvantages of reaming are its potential negative physiologic effects, which include acute respiratory distress syndrome and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (8). The role and timing of reaming remain highly controversial (9). Advances in reamer design and techniques, such as “minimal reaming,” minimize the number of passes and may decrease the embolic load. Reamers with sharp, deep flutes have replaced previous generations of shallow reamers, thereby diminishing the “plunger” effect of reaming. More recently, reamers have been designed to decrease the pressure and heat within the canal by using a suction/irrigation system to cool and clear the products of reaming. Most North American surgeons use reaming when nailing diaphyseal femur fractures, because the risk/reward ratio is still very favorable.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Most diaphyseal fractures can be nailed, regardless of the degree or amount of comminution, angulation, or shortening. Metaphyseal extension is not a contraindication to nailing, although special attention to reduction is required. Nailing is also indicated for pathologic or impending fractures in patients with bone pain or lytic lesions from metastasis.

Intramedullary nailing can be successfully performed antegrade (piriformis or trochanteric entry) or retrograde (through the knee). Although some surgeons may routinely perform retrograde nailing, most surgeons prefer to reserve retrograde nailing for special circumstances such as bilateral femur fractures, ipsilateral femur and tibia (floating knee) fractures, femur fracture in an obese patient, ipsilateral femoral neck/shaft fractures or ipsilateral femur, and pelvis or acetabulum fractures.

There are several contraindications to nailing and include patients of small stature with narrow intramedullary canals who may be at an increased risk for nail incarceration or iatrogenic fracture. They may require excessive reaming to allow safe passage of the nail. Pediatric and adolescent patients with open epiphysis may be better treated with flexible nails that avoid the growth plates. Severe systemic or local infections are also contraindications to nailing. Alternate methods such as external fixation or plating should be considered in these cases. Patients with severe lung injury and long bone fractures often require damage control with a temporary external fixator prior to intramedullary nailing. This allows for improvements in their physiologic state prior to definitive care. An open femur fracture is not a contraindication to primary nailing (10). Most open femur fractures can be safely nailed after the initial irrigation and débridement. However, in highly contaminated femur fractures that would require a “second look” or in cases of prolonged delay (in the authors’ opinion this would be >12 hours) to irrigation and débridement, the surgeon should place an external fixator for temporary stabilization. This will allow the surgeon to reexpose the bone ends at the next operation and gain thorough access to the open fracture zone of injury. Once the zone of injury is deemed thoroughly irrigated and débrided, the definitive intramedullary nail can be inserted.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History and Physical Examination

When planning surgery for intramedullary nailing, careful evaluation of the patient is essential. Age, comorbidities, and concomitant injuries are essential parts of the evaluation. An isolated femur fracture from a high-energy mechanism is a diagnosis of exclusion. The entire axial and appendicular skeleton, as well as the chest and abdomen, must be thoroughly examined to rule out additional injuries. The surgeon should check for open wounds, abrasions, blisters, and swelling not only in the injured thigh but also in all the extremities. A large hemarthrosis of the ipsilateral knee may indicate a patella or tibial plateau fracture or cruciate injury. The peripheral pulses should be carefully documented, and an ankle-brachial index should be calculated if pulses are diminished or not palpable. The surgeon should document a detailed neurological exam looking for deficits in the deep peroneal, superficial peroneal, and tibial nerve distributions. Femoral nerve function will be nearly impossible to ascertain, but careful observation of the patient may give information of quadriceps function if the patients move involuntarily due to pain.

Older patients with osteoporosis and bowing of their femurs require special consideration to prevent an iatrogenic fracture during nailing. Comorbidities are important and may influence patient positioning, direction of nailing, nail type, and the role of reaming. Morbidly obese patients may be better treated with a retrograde nail. If antegrade nailing is required, a lateral position rather than supine position may be helpful. Multiply injured patients with spine fractures or solid organ injuries such as the liver or spleen are more safely nailed in the supine position. In patients with lung injuries and multiple long bone fractures, nailing without reaming or with modified suction-irrigation reamers may minimize fat embolization. Metastatic disease to bone may influence the surgeon to stabilize the entire femur, including the femoral head and neck, to prevent fractures in these locations.

Imaging Studies

High-quality radiographs should be obtained for accurate preoperative planning. A full-length anteroposterior and lateral radiograph is essential. If fracture comminution precludes adequate determination of canal diameter and length, x-rays of the contralateral femur are helpful. Frequently these measurements can be taken intraoperatively from landmarks on the contralateral femur using fluoroscopy.

Dedicated radiographs of the hip and knee, as well as a computed tomography (CT) scan, may help identify fractures of the knee joint or femoral neck (11). A thin-section CT through the femoral neck will identify many, but not all, nondisplaced femoral neck fractures ipsilateral to a femoral shaft fracture (11, 12 and 13). The authors recommend asking for and evaluating the thin cuts (2 mm) through the femoral necks as part of the trauma pelvis CT in patients with femoral shaft fractures. High vigilance for femoral neck fractures is still required for all patients with femur fractures in the perioperative period.

Timing of Surgery

Once the patient has been evaluated and treated for concomitant injuries, the timing of nailing must be considered. Nailing within 24 hours is preferred for those patients without complex medical comorbidities and who are stable for surgery. If an operating room is not available or the patient has a full stomach, the surgeon may have to delay treatment for a few hours. The surgeon should treat the femur fracture as soon as the patient, the operating room resources, and the surgeon are fully ready for surgery. There is no need to operate in the middle of the night by a tired surgeon and hospital crew. However, if surgery will be delayed more than several hours, the surgeon should place the patient in skeletal traction to hold the femur out to length. This is usually more comfortable for the patient and may decrease blood loss. The surgeon should also consider a femoral nerve block or indwelling femoral nerve catheter while the patient waits for surgery (14). For multiply injured patients who require resuscitation, some form of traction is recommended as their physiologic state may deteriorate rapidly. If surgery is delayed >8 to 12 hours, skeletal traction is preferred. A Kirschner wire should be placed in the distal femur or proximal tibia and attached to a tensioned traction bow. This can often be done in the emergency department or intensive care unit under local anesthesia. In the unstable polytrauma patient, damage control orthopedics using external fixation may be preferable to skeletal traction if the patient is going to be in the operating room for life-saving procedures. An external fixator can be applied in the intensive care unit, but this is not ideal. Single-stage conversion of an external fixator to a nail should be done early (ideally within 14 days) to minimize the risk of infection (15). Scannell et al. (16) showed no apparent difference in morbidity or outcome between patients treated with skeletal traction or external fixation in the severely injured patient.

Surgical Tactic

Prior to surgery, the surgeon should develop a surgical plan based on the findings of the physical exam and imaging studies. This plan must be shared with the operating room staff to make sure all the personnel work efficiently. The surgeon should decide patient positioning, whether a fracture table will be used and whether the patient will need damage control techniques (external fixator) or definitive treatment. If the patient is going to be treated

definitively with an intramedullary nail, will the surgeon place the nail retrograde or antegrade? If antegrade nailing is chosen, will the surgeon use a piriformis or trochanteric entry? The surgeon will also need to decide if he/she will ream or not ream. Other key decisions that will need to be determined before the case are the location of the C-arm and if any ancillary reduction devices such as Shanz pins, a crutch, bolsters, etc. will be needed. All of these decisions need to be made before the case starts to be sure the appropriate equipment and resources available. Once the surgical tactic is completed, the surgeon is now ready to execute the plan and perform the operation.

definitively with an intramedullary nail, will the surgeon place the nail retrograde or antegrade? If antegrade nailing is chosen, will the surgeon use a piriformis or trochanteric entry? The surgeon will also need to decide if he/she will ream or not ream. Other key decisions that will need to be determined before the case are the location of the C-arm and if any ancillary reduction devices such as Shanz pins, a crutch, bolsters, etc. will be needed. All of these decisions need to be made before the case starts to be sure the appropriate equipment and resources available. Once the surgical tactic is completed, the surgeon is now ready to execute the plan and perform the operation.

Surgery

For the most part, the anesthesiologist will determine whether a regional or general anesthetic will be most appropriate for the patient and the planned operation. Absolute contraindications for regional anesthetic are head injury, a large blood loss, and coagulopathy.

The trauma surgeon and/or anesthesiologist will most likely determine whether an arterial and/or central line will be needed. In general, unstable patients with a large blood loss or patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities will require arterial and central venous access. A foley catheter is usually indicated to help monitor volume status.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be given based on the patients’ drug allergies and soft-tissue status. An antibiotic with staphylococcus and streptococcus coverage such as a first-generation cephalosporin is recommended for closed fractures. An alternative antibiotic such as clindamycin should be given if the patients have a significant penicillin allergy. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is typically given for 24 hours post-op. Patients with open fractures should receive antibiotics as soon as possible to cover gram-positive organisms (first-generation cephalosporin) for small skin wounds with little to no contamination. If the open wound is more extensive or contaminated, then additional antibiotics should be given to cover gram-negative organisms (gentamycin) and possibly anaerobic organisms (penicillin) if there is significant soil contamination. The appropriate duration of postoperative antibiotics after an open femur fracture is not clearly defined. Continuing antibiotics for 1 to 3 days after the last washout is reasonable based on initial wound contamination.

Patient Positioning

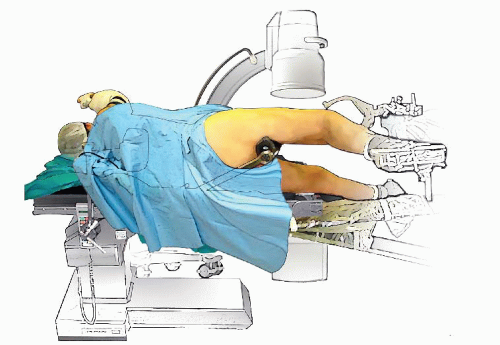

There are several ways to position a patient for femoral nailing, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. Classically patients are positioned either supine or lateral on a fracture table. Traction through the leg extension or using a skeletal traction pin is almost always necessary to restore length and alignment of the shortened femur. Alternatively, nailing on a flat-top radiolucent table can be done, but usually requires a scrubbed assistant, traction with weights off the end of the table, or a femoral distractor to maintain length during the procedure. Kuntscher (2) originally described femoral nailing with the patient in the lateral position on a fracture table (Fig. 22.2). The chief benefit of lateral positioning is that it provides easier access to the piriformis fossa

and facilitates nailing of fractures in the proximal portion of the femur as well as in large or obese patients. Disadvantages of lateral nailing include limitations in patients with multiple injuries and the difficulty judging proper rotation of the extremity. Lateral decubitus nailing on a fracture table is used much less frequently today.

and facilitates nailing of fractures in the proximal portion of the femur as well as in large or obese patients. Disadvantages of lateral nailing include limitations in patients with multiple injuries and the difficulty judging proper rotation of the extremity. Lateral decubitus nailing on a fracture table is used much less frequently today.

Supine nailing on a fracture table (Fig. 22.3) is the most commonly utilized technique for femoral nailing in North America. Benefits include a relatively straightforward setup, familiarity by the operating room staff, improved ability to assess limb length and rotation when both legs are in extension, and it can often be performed without a scrubbed assistant. The major drawback with this method is difficulty gaining access to the piriformis fossa, particularly in large patients.

Supine or floppy lateral positioning on a radiolucent table has recently become more popular due to its simple setup and accommodation of patients with multiple injuries. Multiple procedures can be performed on the same patient without a position change when this method is chosen. The major disadvantage with this technique is accurate restoration of length and alignment that requires a scrubbed assistant for reduction and traction, especially in delayed cases or in patients with large muscle mass. Because most femoral nailings are done supine on a fracture table and it is currently the most universal method of femoral nailing, the rest of the chapter focuses on this technique.

Once the patient has been placed on the fracture table, it is helpful to “bend” the patient’s torso away from the injured side (Fig. 22.4) to improve access to the starting point in the proximal femur. The upper extremity

on the injured side is secured across the chest and held on bolsters, a Mayo stand, or pillows (see Fig. 22.4). With isolated femur fractures, the injured leg is placed into the boot of the fracture table. If a skeletal traction pin is required or is already in place, it is incorporated into the fracture table. A distal femoral traction pin must be strategically placed to avoid interfering with the nailing process. If there are no injuries to the knee joint, many surgeons prefer a proximal tibial pin. We routinely place the noninjured extremity in the contralateral traction boot with the hip and knee in extension so that modest counter traction can be applied through this limb as well (see Fig. 22.4). This stabilizes the pelvis and prevents rotation of the pelvis around the perineal post when traction is applied to the injured limb. Another benefit of nailing with both legs in extension is the excellent ability to assess length and rotation by using the uninjured femur as a guide. Although many surgeons prefer to flex, abduct, and externally rotate the uninjured leg in a well-leg support, we have found this to be less reliable for stabilizing the pelvis and assessing length and rotation.

on the injured side is secured across the chest and held on bolsters, a Mayo stand, or pillows (see Fig. 22.4). With isolated femur fractures, the injured leg is placed into the boot of the fracture table. If a skeletal traction pin is required or is already in place, it is incorporated into the fracture table. A distal femoral traction pin must be strategically placed to avoid interfering with the nailing process. If there are no injuries to the knee joint, many surgeons prefer a proximal tibial pin. We routinely place the noninjured extremity in the contralateral traction boot with the hip and knee in extension so that modest counter traction can be applied through this limb as well (see Fig. 22.4). This stabilizes the pelvis and prevents rotation of the pelvis around the perineal post when traction is applied to the injured limb. Another benefit of nailing with both legs in extension is the excellent ability to assess length and rotation by using the uninjured femur as a guide. Although many surgeons prefer to flex, abduct, and externally rotate the uninjured leg in a well-leg support, we have found this to be less reliable for stabilizing the pelvis and assessing length and rotation.

Once the patient is positioned and secured to the fracture table with both lower extremities in extension, gentle traction is applied to the noninjured injured extremity to keep it from sagging. The next step is to apply traction to the injured extremity to restore the length, alignment, and correct the rotation. For simple and minimally comminuted femur fractures, this is relatively easy to accomplish. However, in patients with comminuted unstable fractures, we use the uninjured side as a reference.

Imaging

The C-arm is brought in perpendicular to the patient from the opposite side, and a posterior-anterior (PA) image of the hip on the injured side is taken. This image is saved to the second screen of the C-arm monitor. A PA image is then taken of the hip on the uninjured side. The uninjured extremity is rotated (usually slightly external) until the PA profile matches the hip from the injured side. Once the two hips match, a PA image of the knee on the uninjured extremity is taken and saved. The injured extremity is then rotated until the knee image on the injured side matches the knee image on the uninjured side. Once the two knee images match, the rotation of the femurs should be correct. The C-arm can now be centered over the fracture site, and traction can be applied or released as needed to restore the length of the injured femur. If the fracture is a simple pattern, rotation and length can be fine-tuned based on matching up the fracture lines like a puzzle. If there is significant comminution, length can be determined by measuring the uninjured femur with a long ruler using the image intensifier (Fig. 22.5). The injured femur can be pulled out to the desired length as needed with the traction boot or traction pin. The most difficult situation is when both femurs are fractured, and there are no normal landmarks to judge length and rotation. In this infrequent scenario, the surgeon takes a lateral image

of the least injured extremity’s hip and rotates the C-arm until a lateral projection of the hip is obtained with about 10 to 15 degrees of femoral neck anteversion. The C-arm is then moved down to the knee, and the knee is rotated (usually slight external rotation is required) until a perfect lateral of the knee is obtained. At this point, the femur should have acceptable rotational alignment. Length should be restored as best as possible using the ligamentotaxis of the fractured fragments as guides to length. Once one side is fixed, then the other side can be matched using the technique described above so that both extremities have symmetric length and rotation. One important technical point to emphasize is that a direct lateral of the hip is difficult to obtain in large patients due to the need to image through the entire pelvis. However, rotating the C-arm 10 to 15 degrees off the true lateral allows adequate visualization in most patients. Once length and rotation have been restored, the two extremities are scissored by lowering the uninjured extremity toward the floor (Fig. 22.6).

of the least injured extremity’s hip and rotates the C-arm until a lateral projection of the hip is obtained with about 10 to 15 degrees of femoral neck anteversion. The C-arm is then moved down to the knee, and the knee is rotated (usually slight external rotation is required) until a perfect lateral of the knee is obtained. At this point, the femur should have acceptable rotational alignment. Length should be restored as best as possible using the ligamentotaxis of the fractured fragments as guides to length. Once one side is fixed, then the other side can be matched using the technique described above so that both extremities have symmetric length and rotation. One important technical point to emphasize is that a direct lateral of the hip is difficult to obtain in large patients due to the need to image through the entire pelvis. However, rotating the C-arm 10 to 15 degrees off the true lateral allows adequate visualization in most patients. Once length and rotation have been restored, the two extremities are scissored by lowering the uninjured extremity toward the floor (Fig. 22.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree