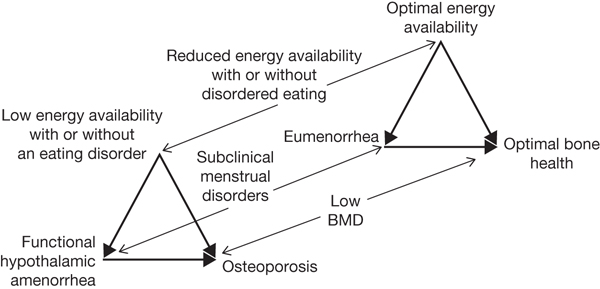

Chapter 9 Marci Goolsby Women’s Sports Medicine Center, Hospital for Special Surgery New York, NY, USA The female athlete triad (“Triad”) refers to the relationship between three components: energy availability, menstrual function, and bone health. The Triad was first described in the early 1990s, and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) published the first position stand on the Triad in 1997 with a revised version published in 2007. The revised version focused on the spectrum of disease seen, rather than only the diagnoses seen at the extreme end of pathology: amenorrhea (lack of menses), low energy availability with or without disordered eating, and osteoporosis. Recognizing athletes at risk who may not yet demonstrate the more severe disease of this spectrum is important for early intervention. There are a myriad of negative consequences of the Triad that are preventable. Thus, there has been a lot of focus on education of athletes, coaches, health care providers and others. Adolescence and young adulthood is a critical time in bone and reproductive health, making the early identification of the Triad important in order to minimize the short-term and long-term consequences. The Triad describes three components and their interrelationship (see Figure 9.1). These three components exist along a spectrum from healthy energy balance to low energy availability with or without disordered eating, normal menstrual function to amenorrhea, and good bone health to osteoporosis. Athletes may demonstrate one or more of these three components and early diagnosis and intervention are critical to preventing further progression of disease. Challenges exist in studies of prevalence due to variable definitions and techniques for studying the components, often relying on inaccurate assessment tools. Despite these challenges, there is evidence for an increased incidence of the Triad components among exercising women, particularly those involved in leanness sports such as endurance (i.e., distance running), weight class (i.e., wrestling), and aesthetic sports (i.e., figure skating). Figure 9.1 Female athlete triad. The spectrums of energy availability, menstrual function, and bone mineral density along which female athletes are distributed (narrow arrows). An athlete’s condition moves along each spectrum at a different rate, in one direction or the other, according to her diet and exercise habits. Energy availability, defined as dietary energy intake minus exercise energy expenditure, affects BMD both directly via metabolic hormones and indirectly via effects on menstrual function and thereby estrogen (thick arrows). Reprinted with permission from Nattiv et al. (2007). Energy availability refers to the balance between dietary calorie intake and exercise energy expenditure. When the calories burned with exercise exceed the calories from nutrition intake, this is referred to as low energy availability. Often, this occurs with disordered eating where the athlete practices unhealthy eating habits such as restricting overall calorie intake or avoiding certain foods but without meeting the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of an eating disorder. Clinical eating disorders can also occur such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified. Recognition of the eating disorder signs is particularly important in the Olympic athletes as elite athletes are three times more likely to have an eating disorder than the general population (Sundgot-Borgen and Torstveit, 2004). Excessive exercise is often a contributing factor as well, particularly in elite athletes, and the athlete may be exercising more than is appropriate for their training in order to lose weight. The imbalance can also be accidental in the case of an athlete who has an increased or overall strenuous training without appropriate adjustment of her nutrition. Low energy availability in turn disrupts the hormonal pathways, which is manifested clinically as menstrual dysfunction, or irregular periods. Inadequate nutrition can have detrimental effects on performance through associated fatigue, dehydration, vitamin deficiencies, anemia, higher risk of injury, depression, and poor recovery. The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal hormone axis is disrupted by the low energy availability and can lead to a number of reproductive disturbances, most often seen clinically as oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea. Oligomenorrhea refers to prolonged time between menses (more than 35 days). Primary amenorrhea is lack of onset of menstruation (menarche) by age 15 years. Secondary amenorrhea refers to lack of menses for more than 3 months after menarche has occurred. Specifically, the type of amenorrhea seen in the Triad is functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, describing the disruption of the hormone axis. The incidence of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea varies by sport but has been reported as high as 65% in distance runners (Dusek, 2001). Other menstrual dysfunction can occur that is not as clinically apparent such as anovulatory cycles and luteal phase dysfunction; therefore, normal menses does not always mean low energy availability is not present. The consequences of disrupted hormonal function include both short- and long-term effects on fertility and bone health. Both nutritional deficits and hormonal disruption can have a negative impact on bone health, leading to an increased risk of stress fractures as well as the risk of developing early osteoporosis. Research has shown a dose–response effect of Triad risk factors on low bone mineral density (BMD) incidence (Gibbs et al., 2013). A woman reaches her maximum bone health potential in young adulthood, thus making this a critical time for adequate nutrition and avoidance of negative factors. With prolonged nutritional and menstrual disturbances, this negative impact on bone may not be fully reversible. Delayed menarche, history of oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and low BMD have all been associated with an increased risk of stress injuries to the bone. These can significantly impact an athlete’s career due to missed training and competition. The impact of osteoporosis on morbidity and mortality in the older population has been well described with half of all women suffering an osteoporosis-related fracture over the age of 50 and a quarter of seniors who break their hip will die within 1 year.

Female athlete triad

Introduction

Components and consequences

Energy availability

Menstrual function

Bone health

Screening and risk factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree