Chapter 27 Failed Cartilage Repair

Clinical Evaluation

Imaging

Standard radiographs for cartilage injury should include bilateral knees in at least three views: anteroposterior (AP) weight-bearing view; non–weight-bearing, 45-degree flexion lateral view; and axial (Merchant) view of the patellofemoral joint. Additional views include a 45-degree flexion posteroanterior (PA) view, which may be useful to identify subtle joint space narrowing. A full-length alignment view of the affected and unaffected limb may help evaluate the mechanical axis and associated varus or valgus malalignment (Fig. 27-1). A computed tomography (CT) scan may be useful to assess the patellofemoral joint and the associated tibial tubercle–trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance.1,13 This measurement is particularly useful in patients with patellar instability when associated with chondrosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are often used in the preoperative assessment of previously failed cartilage repair procedure. They provide a detailed assessment of lesion size, depth, quality of subchondral bone, and presence or absence of bony fractures. MRI may also confirm the presence of associated ligamentous, meniscal, or other soft tissue pathology.

Treatment

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative therapies play a role for patients with previous cartilage repair surgery. Patients with unreasonable expectations or goals, failed multiple procedures, advanced physiologic age with low demand, or unwilling to have further surgery may be amenable to these conservative modalities. These therapies include oral medications, physical therapy, weight loss, and injections (cortisone and hyaluronic acid derivatives). Oral medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral chondroprotective agents (e.g., glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate) are commonly used in symptomatic patients. Although the precise mechanism of action of these medications has not been elucidated, it has been hypothesized that glucosamine stimulates chondrocytes and synoviocytes to increase production of extracellular matrix, whereas chondroitin manages to inhibit fibrin clot formation and degradative enzymes.2

Cortisone injections are commonly used in practice for short-term pain relief because of the anti-inflammatory action of the steroids. Similarly, intra-articular injections containing hyaluronic acid provides viscosupplementation, resulting in significant pain reduction and improved function.5,7,12,14

Operative Treatment

Surgical managements of articular cartilage lesions can be grouped into three categories:

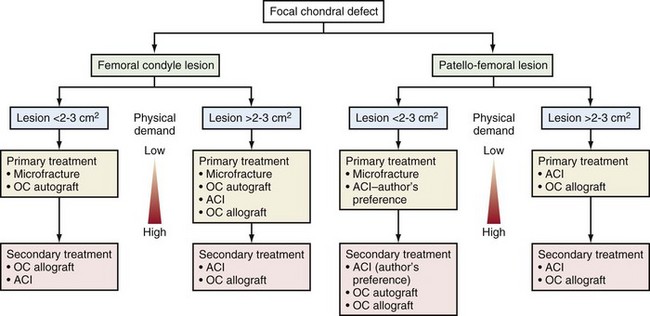

The appropriate treatment for any given cartilage lesion is patient- and defect-specific. Lesion-specific variables include lesion size, location, depth, geometry, and bone quality; patient-specific variables include the patient’s physiologic age, activity level, goals and expectations, and previous surgeries. Consideration of these variables and the associated comorbid conditions allow the management of cartilage lesions to be considered as part of an algorithm from the least invasive to the most invasive intervention (Fig. 27-2). The overall goal is to restore the patient’s function and ameliorate symptoms using the least invasive technique. In the setting of a revision procedure, the least invasive procedure can often be exhausted, with undesirable outcomes requiring the surgeon to consider more invasive techniques for cartilage restoration while also addressing the reasons for primary failure, as noted earlier.

Figure 27-2 Algorithm used to guide decision making for primary and revision articular cartilage repair.

Palliative Procedures

Arthroscopic débridement and lavage are usually performed as a first-line treatment and considered for patients suffering from an acute injury causing pain and incongruency caused by a dislodged piece of cartilage (<2 cm2). Simple irrigation to remove debris, inflammatory cytokines, and proteases may help alleviate the patient’s symptoms. In a revision setting, an arthroscopic débridement may temporarily alleviate the patient’s symptoms and may also be used as a diagnostic tool to assess cartilage abnormalities and concomitant pathology. This may be especially true in the setting of previous autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) with resultant graft hypertrophy,4 graft resorption with loose bodies, or advanced joint degeneration.

Reparative Procedure

Small- to medium-sized (2 to 3 cm2), full-thickness chondral defects can be managed using marrow stimulation techniques, such as microfracture, subchondral drilling, and abrasion arthroplasty. Microfracture involves the use of a surgical awl on the subchondral bone to allow migration of marrow elements (mesenchymal cells). This migration results in the formation of a surgically induced fibrin clot at the defect site and the production of fibrocartilage. The newly formed repair tissue possesses a preponderance of types I and II collagen,11 rendering it biologically and mechanically inferior to hyaline cartilage. This is especially helpful when prior procedures have been only partially successful in creating a complete defect repair (Fig. 27-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree