CHAPTER 103 Failed Back Surgery

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) is a non-specific term that implies the final outcome of surgery did not meet the expectations of both the patient and the surgeon that were established before surgery.1 It should not and does not suggest that the patient failed to get total pain relief or did not return to full function.

The patient must also have realistic expectations, and must rely to some degree on the surgeon’s input. In patients with chronic pain, an improvement in 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) or visual analog score (VAS) of 1.8 units is equivalent to a change in pain of about 30%, which will be considered by most patients as a ‘somewhat satisfactory result.’2 An improvement in NRS or VAS of 3 units or more is equivalent to a change in pain of about 50%, which most patients will consider an ‘extremely satisfactory result.’

STRUCTURAL ETIOLOGIES OF FAILED BACK SURGERY

In this section, the author will briefly review the most common structural causes of FBSS based on published data.3–5 These are lateral canal stenosis (foraminal stenosis), recurrent or residual disc herniation, one or more painful discs, neuropathic pain, facet joint pain, and sacroiliac joint pain. It is interesting to note that the causes of FBSS and the causes of chronic low back pain (LBP) are quite similar. By combining a careful history, physical examination, and specialized testing, the structural cause of FBSS can be delineated in more than 90% of patients.4,5 In some patients, the structural cause of the FBSS was present prior to surgery and was not adequately addressed (e.g. painful disc, lateral canal stenosis, facet or sacroiliac joint [SIJ] pain). In others the problem occurred after surgery, either as a direct consequence of the surgery (e.g. SIJ pain after fusion, pseudoarthrosis, etc.) or as new and unrelated pathology.

In 1981, Burton et al. reported an analysis of several hundred patients with FBSS.3 They found that about 58% had lateral canal stenosis (foraminal stenosis), 7–14% had central canal stenosis, 12–16% had recurrent (or residual) disc herniations, 6–16% had arachnoiditis, and 6–8% had epidural fibrosis. Other less common causes in their series included neuropathic pain, chronic mechanical pain, painful segment (disc) above a fusion, pseudoarthrosis, foreign body, and surgery performed at the wrong level. They were unable to establish a definitive diagnosis in less than 5% of their patients despite the fact that their study was done early in the computed tomography (CT) scan era and well before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. They did use discography.

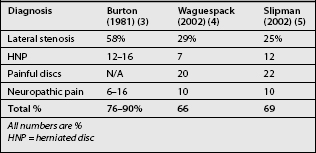

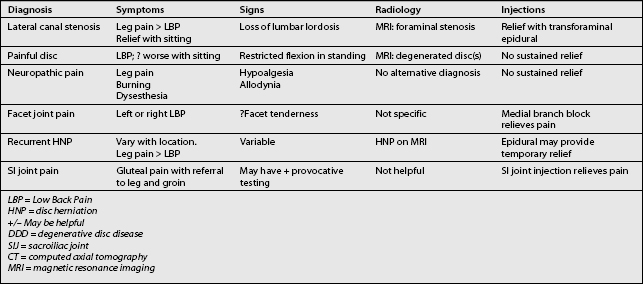

There have been major advances in diagnostic testing since the Burton paper. In 2002, Waguespack et al.4 and Slipman et al.5 each independently reported their results of evaluations of patients with FBSS (Table 103.1). Waguespack et al. performed a retrospective review of 187 patients who presented to a tertiary care spine center. They established a predominant diagnosis in 95% of their patients. Slipman et al. performed a similar study in which they reached a diagnosis in more than 90% of patients as well. In these two recent studies the most common structural causes of FBSS were foraminal stenosis (25–29%), painful disc (20–22%), pseudoarthrosis (14%), neuropathic pain (10%), recurrent disc herniation (7–12%), instability, facet pain (3%), and sacroiliac joint pain (2%), among some others (Table 103.2).

Table 103.2 Differential Diagnosis of Common Causes of FBS by Symptoms, Signs, Radiology, and Injections

Several authors have presented their unquantified impressions and experiences regarding the causes of FBSS. Fritsch et al.6 reviewed 136 patients who had revision surgeries after clinical failure of an initial laminectomy and discectomy, and found a high prevalence of recurrent disc herniations and instability. Kostuik7 reviewed the potential causes of failure of decompression, but provided no quantitative data.

In this chapter, the author has used functional definitions which are a composite of those proposed by the North American Spine Society8 and the International Association for the Study of Pain,9 modified by personal clinical experiences.

Lateral canal stenosis

Lateral canal stenosis was found in 25–29% of FBSS patients in the more recent studies, but was twice that 25 years ago.3–5 The lower prevalence in later studies may be due to better preoperative recognition of the condition and more meticulous decompression.

Lateral canal stenosis usually presents with pain that is predominantly in one leg or buttock region (see Table 103.2). The leg and gluteal pains are usually worsened by standing and walking and improved by sitting. MRI or CT scan must show narrowing of the nerve root lateral canal at the index level or an adjacent segment. Lateral canal stenosis may be characterized as ‘up-down stenosis’ due to loss of disc space height or ‘front-back stenosis’ due to facet hypertrophy and osteophyte formation. There is usually at least temporary relief of leg pain after transforaminal epidural blockade of the suspected nerve root.10,11

Painful discs

One or more painful discs were the cause of FBSS in about 21% of patients.3–5 Painful discs may occur at the index level, adjacent level, and occasionally at the level of a prior posterolateral fusion.11 In the Waguespack study,4 painful discs were responsible for FBSS in 31 (17%) patients who did not have prior fusion and 5 (3%) additional patients had a painful disc at a level contained within a prior solid fusion.

It is clear that discs have the substrate to become painful. They are richly innervated with nerve endings that have the potential to be nociceptive.12,13 In the normal disc, nerve endings are limited to the outer third of the anulus. In the degenerated disc, there is proliferation of nerve endings, and in 40% of severely degenerated discs, the nociceptors have grown inward to reach the nucleus.12

Discogenic pain presents with LBP with or without referred buttock or leg pain (see Table 103.2). Painful discs usually appear desiccated and may be narrowed on MRI scan. Schwarzer et al. found no symptoms or signs that are specific for discogenic pain,14 but there may be a few clues.15 Discogenic pain is usually worsened by sitting and by transition from sitting to standing.15 Pain may be improved somewhat by standing or walking. During examination, pain is usually worsened by flexion during standing, which is also decreased due to pain. There may be tenderness over the spinous processes, but not over the facet joints.

Discography is often used to confirm the clinical impression of discogenic pain. It is controversial in chronic LBP and even more so in patients with FBSS.16–18 In every instance, discography must be interpreted very carefully and only in conjunction with the history, examination, imaging studies, and psychological status of the patient.19 The value of discography at a disc that has had prior surgery is not totally clear, but may be useful when carefully interpreted.13 When the diagnosis of discogenic pain is suggested by history and examination, MRI shows only the one bad disc, and other potential causes of LBP are excluded, there is probably no need to perform discography. If discography is used in the setting of FBSS and probable discogenic pain, it is probably most useful to prove other discs are not involved.

Disc herniation

Recurrent or residual disc herniation occurred 7–12% of patients with FBSS.3–5 In the presence of epidural or perineural fibrosis and a nerve root that is surrounded by scar, a disc herniation may cause more leg pain than expected if there were no fibrosis.

The symptoms of recurrent or residual disc herniation (HNP) depend on its location (see Table 103.2). A midline HNP presents as discogenic LBP. Posterolateral HNP will usually present with a predominance of leg pain in the distribution of a single dermatome, but if the disc is sufficiently damaged internally, there can be a significant amount of low back pain as well. There will be MRI evidence of the disc herniation.

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain was the predominant problem in 9% of the author’s patients.4 Burton et al. observed neuropathic pain in less than 5% of their patients.3 It is not clear if there has been an increase in nerve root injury or an increased recognition of neuropathic pain. Nerve roots can be damaged during surgery, but damage is more likely due to prolonged unrelieved compression by spinal stenosis or disc herniation. The incidence of arachnoiditis may be decreasing, perhaps because oil-based myelography is no longer performed.

Neuropathic pain implies that pain arises from nerve injury or dysfunction. There is a predominance of leg pain, which is usually present in one or two adjacent dermatomes. In classic presentations, the pain is described as burning or dysesthetic, but in neuropathic disorders and FBSS this may not be the case (see Table 103.2). Pain is usually constant but it may be worsened by activity because the damaged nerve is sensitized and minor biomechanical changes may worsen pain. In pure neuropathic pain, there is no evidence of nerve root compression on MRI or CT scan.

Facet syndrome

Pain that arises from the facet joint is responsible for the pain in about 3% of patients with FBSS and 15–30% of patients with chronic LBP.5,20 The facet joint is susceptible to inflammation, damage during surgery, or the mechanical stresses of fusion at a segment below.

There are no data that specifically address the symptoms or signs of facet syndrome in patients with FBSS, but several papers have addressed the problem in chronic LBP.15,20–24 Schwartzer et al. felt there were no symptoms typical for facet joint pain, although the presence of midline LBP was not likely in facet syndrome.21 Others feel there are symptoms that are suggestive (see Table 103.2).22,24 Pain is more likely to be experienced just lateral to the midline and is frequently referred to one or both gluteal regions. Pain is better when the patient is lying supine.22 It is less severe sitting than standing or walking, and pain is not worsened during transition from sitting to standing.25 Examination findings are not specific, but there may be tenderness with palpation directly over the joints but not over the spinous processes, and more pain with extension than flexion while standing.

As discussed elsewhere in this text, the diagnosis of facet joint pain is made by intra-articular infusion of local anesthetic or blockade of the medial branches of the primary dorsal rami that serve the putative painful joint. The preferred treatment is radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN), which is successful in a high percentage of well-selected patients.26–29 RFN generally relieves pain for 9–12 months and then it can be repeated, and Schofferman and Kine have shown that repeated RFN remains effective.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree