18. Eye infections

Ocular defence mechanisms

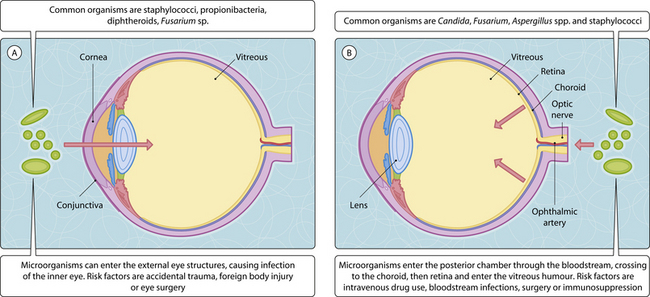

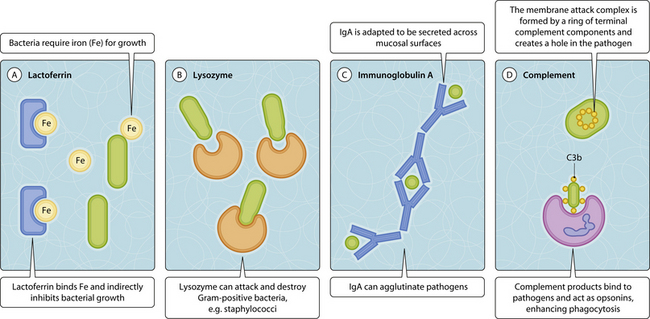

The eye is normally well protected against infections (Fig. 3.18.1). Physical factors such as the blinking action of the eyelid, the tear film and the conjunctiva help to prevent attachment of microorganisms. The outer eye contains antimicrobial compounds produced by the tear film (Fig.3.18.2) and phagocytic by conjunctival epithelial cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

A variety of different pathogens affect different anatomical structures, resulting in disease of varying severity, ranging from relative common and less severe (e.g. stye) to permanent loss of visual acuity or even blindness (retinochoroiditis). There are two main routes of infection. The most common is direct inoculation of pathogens into the eye (exogenous infections) through trauma (i.e. surgery, foreign body, contact lenses). The second route is much rarer and introduces pathogens into the posterior part of the eye (retina/choroids) via the bloodstream (endogenous infection) (Fig.3.18.1).

Infections of the external eye structures

Neonatal conjunctivitis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae (ophthalmia neonatorum) and Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes D–K (inclusion conjunctivitis) are serious conditions acquired from the female genital tract during birth. It can progress to keratitis, perforation and blindness. Trachoma is a severe C. trachomatis serotype A–C infection commonly found in the tropics in all age groups. Patients present with chronic inflammation of the conjunctival epithelium, which can lead to intense scarring and blindness. Early treatment with tetracycline in adults or erythromycin in children and pregnancy is essential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree