Exposures of the Acetabulum

S. Andrew Sems

Key Points

Ilioinguinal Approach

The ilioinguinal approach allows access to visualize the entire anterior column of the acetabulum, as well as palpable access to portions of the posterior column.1–3 Multiple neurovascular structures must be identified, mobilized, and carefully protected during this exposure. Modifications to this exposure allow full access to the quadrilateral surface of the acetabulum as well.4–9 This exposure involves opening portions of the abdominal wall, and careful closures are required to prevent the formation of hernias.

Indications

Positioning

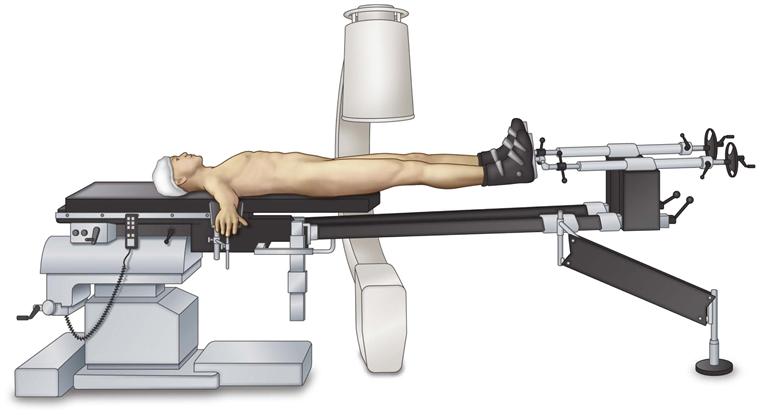

The ilioinguinal approach is performed with the patient in the supine position (Fig. 16-1). The arms of the patient may be tucked at the side, but placing them in an abducted position may facilitate exposure of the lateral window and may improve the ability to obtain intraoperative oblique radiographs of the operative region. A radiolucent fracture table with a perineal post and leg traction can be used with this approach to assist in obtaining reduction of the fracture. A urethral catheter should be placed in the patient’s bladder before the surgical site is prepared, to decompress the bladder.

Figure 16-1 The patient is positioned supine on a radiolucent fracture table. The arms are abducted and intraoperative image intensification is positioned on the contralateral side.

Landmarks

The iliac crest is palpated from the anterior superior iliac spine posteriorly. Additionally, the pubic symphysis is palpated and the midline of the abdomen is located. The operative field is prepared from an area proximal to the superolateral portion of the iliac crest to the superior portion of the introitus or the top of the penis. The umbilicus can be carefully draped out of the field. Care should be taken to note scars from previous herniorrhaphies or surgeries in the inguinal region and prior Pfannenstiel incisions from gynecologic/urologic surgery; previous cesarean sections should be noted, and these can be incorporated into the surgical incision.

Technique

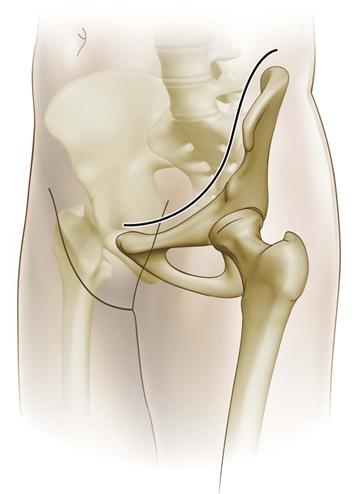

1. The skin over the lateral aspect of the iliac crest is incised from the anterior superior iliac spine posteriorly 10 to 15 cm depending on the size of the patient (Fig. 16-2). Dissection is carried through the skin subcutaneous tissue with hemostasis gained along the way. The fascia over the hip abductors and the fascia over the abdominal musculature are identified. These fasciae come together into an aponeurosis over the proximal lateral aspect of the iliac crest. This aponeurosis is incised in line with its fibers along the iliac crest (Fig. 16-3).

Figure 16-2 The skin incision courses along the proximal aspect of the iliac crest, extending to a point 2 cm above the pubic symphysis and then continued 3 to 5 cm past the midline of the abdomen.

Figure 16-3 The aponeurosis of the abdominal musculature and hip abductors is identified and split along the edge of the iliac crest.

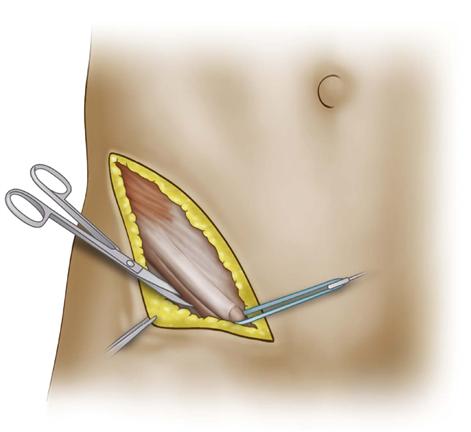

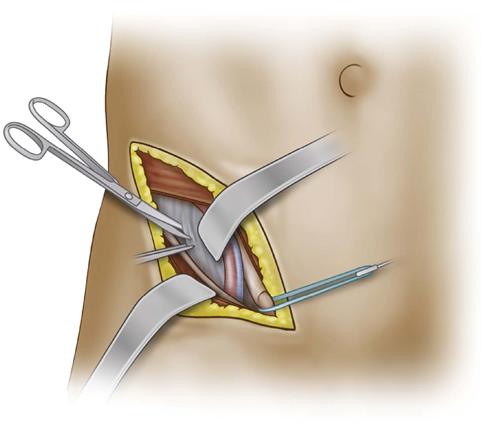

6. Once the incision is carried to the level of the abdominal fascia, the fascia of the external abdominal oblique is identified as it courses toward the external inguinal ring. The inguinal ligament is identified coursing from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle. The spermatic cord or round ligament should be identified exiting from the superficial inguinal ring. A Penrose drain or surgical tape can be placed around this structure for control and mobilization (Fig. 16-4). The external abdominal oblique is dissected in line with its fibers and is incised 3 to 5 mm proximal to the inguinal ligament, leaving tendon on each side for later repair (Fig. 16-5). The external abdominal oblique can be split to a point just distal to the superficial inguinal ring, allowing this ring to be maintained in place to decrease the potential for the development of postoperative inguinal hernias.

Figure 16-4 The skin incision is carried distally; the spermatic cord is identified and circumferential control is gained with a tape or Penrose drain. The fibers of the external abdominal oblique and inguinal ligaments are identified.

Figure 16-5 The fibers of the external abdominal oblique are split 4 to 5 mm proximal to their insertion on the inguinal ligament distally to a point just distal to the external inguinal ring.

7. The conjoined tendon of the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique is identified. Before this is split, care should be taken to identify the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh. This nerve courses over the iliopsoas muscle and exits laterally near the anterior superior iliac spine. This nerve may not be able to be preserved in all cases, and careful preoperative discussion with the patient should include the potential for postoperative lack of sensation in the distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Once the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve has been identified, the conjoined tendon of the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique is incised in line with its fibers (Fig. 16-6). This should be done 2 to 4 mm proximal to its insertion on the inguinal ligament. This will allow later repair of this fascia in two separate layers to decrease the chance of postoperative hernia.

Figure 16-6 The conjoined tendon of the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique is incised 2 to 3 mm from their insertion on the inguinal ligament, leaving an adequate amount of tendon on each side for repair during closure.

8. Circumferential control of the iliopsoas with the femoral nerve should be obtained (Fig. 16-7). Care should be taken to make sure that the nerve and the psoas stay together as a single unit. A large, curved clamp can be advanced behind and around the psoas and used to guide a Penrose drain or surgical tape around the neuromuscular unit of the psoas and femoral nerve for retraction and control.

Figure 16-7 The femoral nerve and the psoas muscle have been mobilized and a tape or Penrose drain passed behind these structures for circumferential control. The iliopectineal fascia is identified medial to the psoas and the femoral nerve. The iliopectineal fascia is being held by forceps.

9. Careful dissection along the iliopectineal fascia is necessary to mobilize the external iliac vessels. These vessels can be identified by palpation of the pulse, and careful dissection mobilizes the vessels medially. With constant protection of the external iliac vessels, the iliopectineal fascia can be split down to the pelvic brim (Fig. 16-8).

Figure 16-8 Dissection medial to the iliopectineal fascia mobilizes the external iliac vessels, and a Deaver retractor is used to retract the vessels as the iliopectineal fascia is split to the pelvic brim.

10. The fascia of the rectus abdominis is identified as it inserts onto the pubic tubercle (Fig. 16-9). This can be incised in a transverse direction to gain access in the space of Retzius. The rectus abdominis should be transected so that the fascial incision is in continuity with the release of the external iliac oblique, as well as the conjoined tendon of the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique.

Figure 16-9 Dissection beneath the spermatic cord allows transection of the rectus abdominis tendon on the operative side.

11. Once the iliopectineal fascia and the rectus abdominis are released, circumferential control of the external iliac vessels can be obtained, and a large, curved clamp can be advanced behind the vessels and used to guide a Penrose drain or surgical tape to maintain control of the vessels (Fig. 16-10). At this point, the three windows of the ilioinguinal approach have been exposed, and the desired surgical procedure can be performed.

Figure 16-10 Circumferential control of the external iliac vessels and the spermatic cord allows exposure of the medial window and bladder and access into the space of Retzius.

Stoppa Approach

Indications

The Stoppa approach can be used for exposure of the anterior pelvic ring and in conjunction with the lateral window of the ilioinguinal approach for exposure of the acetabular region. This exposure utilizes an extraperitoneal approach with retraction of the bladder, bowel, and external iliac vessels.10–12 The Stoppa approach gives access to the quadrilateral surface of the acetabulum and to the low anterior column, the superior pubic ramus, and the pubic symphysis.13,14

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table. The arms can be tucked at the side, although an abducted position may make intraoperative oblique imaging easier, because the arms will not obscure the images. A urethral catheter should be placed in the patient’s bladder before the surgical site is prepared, to decompress the bladder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree