As noted in research on frailty in women, regular exercise can limit age-related functional decline. However, physical activity has been implicated in the etiology of such musculoskeletal disorders as osteoarthritis. Proper exercise plans must strike a balance between promoting health and limiting the risk of injury. This article discusses age-related musculoskeletal changes and gender-specific conditions that may predispose midlife and older women to musculoskeletal injuries. The controversy about how physical activity may relate to osteoarthritis is discussed, along with common osteoarthritic-related spinal and appendicular conditions. Exercise prescription for women is briefly presented. The consistent message in the literature is that exercise is a safe and powerful tool to prevent and treat many medical, psychological, and musculoskeletal conditions in females at midlife and beyond.

The health-promotion aspects of exercise and physical activity have been clearly documented and substantiated in the medical literature . Many individuals turn to exercise to manage or prevent chronic medical conditions, control or reduce body weight, and reduce stress . It has been shown that exercise can reduce the risk of breast cancer in women . Exercise is positively correlated with cognitive function in older persons . Moreover, exercise is an effective means of rehabilitation and is thought to contribute to injury prevention and functional ability in older persons .

Functional limitations

Identifying and managing functional limitations is an ever-increasing task for health care practitioners, especially those caring for aging females. Fifty-two million Americans are estimated to be living with physical limitation and disability secondary to injury, disease, birth defects, and the aging process . Several researchers have identified a gender difference in reporting disability. Women are more likely to self-report disability than men . A recent cross-sectional study of women of multiple races in an age range of 40 to 55 years found that approximately 20% self-reported limitations in physical functioning . Clarification is needed regarding the role of age-related musculoskeletal changes, injuries, and diseases in causing these limitations. Further, exercise is an important component of the functional restoration program and must be prescribed in a safe and efficient manner. Over the past two decades, women with a wide variety of medical conditions and physical disabilities have been counseled to partake in regular exercise programs. For some women who missed the boom in women’s athletics after the early 1970s and Title IX, this may be their initial foray into exercise. Others have been active in sports all their lives or just later in life, perhaps following in the footsteps of their daughters. As in other age groups, exercise novices may be at risk of different musculoskeletal injuries than those common to women experienced in regular exercise. Sports-specific mechanisms of injury should be considered. Understanding the exercise, physical-activity, and previous-injury history of one’s patient is important for diagnosing and managing her musculoskeletal injury. Remember too that injuries in older females impact a system with shrinking physiological reserves. Lifestyle issues and changes associated with aging must be considered when evaluating women and exercise. For example, postpartum pelvic floor weakness can be the precursor to urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, and lumber pain later in life. Soft tissue atrophy and bone density loss in the setting of declining estrogen levels cause changes in strength and posture that may predispose a woman to injury in the perimenopause and postmenopause period. In a system with reduced estrogen, pain related to the musculoskeletal system may be more symptomatic . Master athletes have degenerative changes of the spine and extremities that may limit joint mobility, leading to altered movement patterns and increased injury risk.

Midlife and cardiovascular disease risk profile

Women in midlife tend to gain weight and develop a variety of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It has been shown that women who are physically active tend to be leaner and have a better lipid profile (higher high-density lipoprotein and lower low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and glucose) than women who are not physically active. The impact of physical activity on health outcomes is beneficial. In cross-sectional studies, physical activity was significantly predictive of body mass index . In a longitudinal study, an increase in sports participation or exercise was associated with decreases in weight and in waist circumference . An Australian study of an intervention involving diet and exercise showed significant improvements in weight, body mass index, waist circumference, and diastolic blood pressure . In a clinical trial in the United States, physical activity and diet together were successful in preventing weight gain from pre-, to peri-, to postmenopause and reduced rises in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose . The same study reported later that the progression in intima-media thickness, a measure of atherosclerosis, was slowed in the intervention group . In the Nurses’ Health Study, obesity (whether measured by body mass index or waist girth) and physical inactivity independently contributed to the development of coronary heart disease in women followed over 20 years .

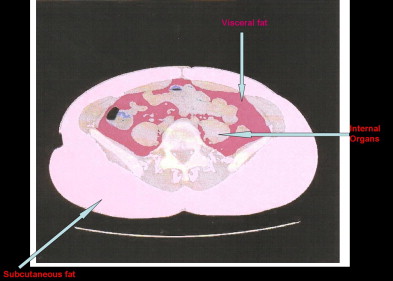

Menopause itself, rather than age alone, brings an increase in cardiovascular disease risk. Physical activity may be able to ameliorate this risk. A cross-sectional study of a biracial sample of women at midlife demonstrated that physical activity negatively correlated with intraabdominal fat independent of multiple covariates as measured by CT ( Fig. 1 ). Intraabdominal fat is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease. The study shows that motivating white and black women to increase their physical activity during their middle years can positively modify age-related increases in intraabdominal fat, which in turn may improve cardiovascular disease risk profiles. In addition, mood has been shown to have an independent effect on cardiovascular disease. Depression and depressive symptoms were significantly associated with cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality . The same researchers found that the associations between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance and risk for diabetes in a sample of middle-aged women were largely mediated by central adiposity, as assessed by waist circumference . Exercise and physical activity can improve mood, providing another means to improve one’s cardiovascular disease risk profile in midlife.

Midlife and cardiovascular disease risk profile

Women in midlife tend to gain weight and develop a variety of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. It has been shown that women who are physically active tend to be leaner and have a better lipid profile (higher high-density lipoprotein and lower low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and glucose) than women who are not physically active. The impact of physical activity on health outcomes is beneficial. In cross-sectional studies, physical activity was significantly predictive of body mass index . In a longitudinal study, an increase in sports participation or exercise was associated with decreases in weight and in waist circumference . An Australian study of an intervention involving diet and exercise showed significant improvements in weight, body mass index, waist circumference, and diastolic blood pressure . In a clinical trial in the United States, physical activity and diet together were successful in preventing weight gain from pre-, to peri-, to postmenopause and reduced rises in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose . The same study reported later that the progression in intima-media thickness, a measure of atherosclerosis, was slowed in the intervention group . In the Nurses’ Health Study, obesity (whether measured by body mass index or waist girth) and physical inactivity independently contributed to the development of coronary heart disease in women followed over 20 years .

Menopause itself, rather than age alone, brings an increase in cardiovascular disease risk. Physical activity may be able to ameliorate this risk. A cross-sectional study of a biracial sample of women at midlife demonstrated that physical activity negatively correlated with intraabdominal fat independent of multiple covariates as measured by CT ( Fig. 1 ). Intraabdominal fat is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease. The study shows that motivating white and black women to increase their physical activity during their middle years can positively modify age-related increases in intraabdominal fat, which in turn may improve cardiovascular disease risk profiles. In addition, mood has been shown to have an independent effect on cardiovascular disease. Depression and depressive symptoms were significantly associated with cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality . The same researchers found that the associations between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance and risk for diabetes in a sample of middle-aged women were largely mediated by central adiposity, as assessed by waist circumference . Exercise and physical activity can improve mood, providing another means to improve one’s cardiovascular disease risk profile in midlife.

Goals of article

This article addresses musculoskeletal disorders that can present in women at midlife and later. Beyond understanding the disorders and their management, individuals caring for women must recognize that rehabilitation goals may differ across a woman’s life span. For some women, returning to competition as soon as possible, without risking ongoing injury, is their challenge. For others, returning to independent performance of activities of daily living may suffice. In moving forward with both basic science and clinical issues, clinicians must continue to examine how activity modifies the musculoskeletal system, both negatively and positively, thus making the best use of exercise for promoting health, preventing injury, and fostering rehabilitation. The task for health care practitioners and exercise scientists is to identify the appropriate “dosing” of exercise to achieve desired goals and avoid undesirable side effects. Nowhere is this more relevant than with the aging female. For example, clinicians must develop exercise programs that limit joint injuries and decrease the force of impacts and the size of torsional loads in high-impact activities. Such exercise programs would diminish the risk of osteoarthritis while delivering site-specific loading of bone to enhance osteogenesis and limit postmenopausal osteoporosis. Thankfully, first-rate research continues on these challenging fronts.

The aging process

As the body ages, it loses its capacity to adapt because of structural change and loss of reserve in multiple-organ systems. As early as the fourth decade of life, a decline in capacity begins, involving the cardiovascular, pulmonary, hormonal, thermoregulatory, and nervous systems. This decline contributes to a decline in health and function. Changes particular to the musculoskeletal system can lead directly to painful and disabling conditions in the aging female and are discussed below. When considering a current musculoskeletal condition, clinicians should keep in mind that concurrent medical conditions, the effects of previous illnesses and injuries, and the side effects of medical treatments may be implicated. Certain behaviors earlier in life, in particular those related to physical activity, may be implicated in a real-time musculoskeletal condition but are not modifiable later in life. For instance, strong evidence indicates that physical activity as a youth contributes to peak bone density . Previous injury to a joint has been associated with osteoarthritis . However, it is important to consider the contemporaneous effects of such behaviors for current and future health concerns when dealing with an older population.

Musculoskeletal changes associated with aging

Bone resorption is age-related with bone density decreasing after the age of 50. This is likely related more to loss of bone volume than mineralization, the latter being largely unaffected by the aging process alone. Osteoporotic vertebral fractures are a more common cause of morbidity in elderly women than in elderly men. Bone density, mineral content, and bone strength losses can be ameliorated through more physical activity. This can be affected regionally. For instance, study participants performing calisthenics and low-impact aerobics increased their lumbar spine bone density . A recent review article reported that progressive-resistance training has been shown to have a more potent impact on bone density than cardiovascular exercise . Refer to the chapter on osteoporosis by Sinaki in this issue for a more comprehensive review of this subject.

The joint capsules become stiffer with age, which leads to a loss of active and passive range of motion. Articular cartilage degeneration is related to age, as well as to joint geometry, sex, injury, activity history, and genetics. Age-related proteoglycan structural changes have been identified and are more fully discussed in the osteoarthritis section below. Functional limitations frequently become the final common pathway of loss of range of motion, strength, and endurance. Radiographic studies have demonstrated that disc degeneration is found uniformly by the eighth decade of life . This is associated with spondylosis, including osteophytes at the vertebral endplates and zygoaphophyseal joints. Degenerative changes in collagen are also in part age-related and occur at the cellular and morphological level. Most studies of age-related changes in tendons and ligaments have focused on the peripheral joints, with the anterior cruciate ligament most commonly studied. Decline in the proprioceptive function of these tissues has been documented . Muscle demonstrates the most evident changes with aging. These changes include loss of muscle mass and decline in the number of motor units, especially type II fibers . This results in a reduced ability to generate force, which can impact functional activity. Muscle mass is a major determinant of age- and gender-related differences in strength. Once function is impaired, a downward spiral of deconditioning or injury can bring significant morbidity. Globally, the reaction time of elders is reduced due to multiple peripheral and central factors. An example of the former is the age-related slowing of motor and sensory nerve conduction velocities. Motor unit recruitment declines centrally. Comorbid factors in the elderly include chronic disease processes and medications directly or indirectly impacting the nervous system. Sensory changes affecting the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems can be age-related or illness-related. Any decline in sensory processing affects the motor responsiveness. Postural control is impaired and can lead to loss of balance. Falling and the fear of falling can be debilitating. Health care practitioners for women must recognize how these physiological and biomechanical changes affect health and function. Functional loss leads to safety concerns and further deconditioning, causing a vicious downward spiral, at times with high morbidity and mortality. This can be a precipitous decline, such as that following a hip fracture in a frail, debilitated elderly female, or a more gradual decline, such as when an elderly female with osteoarthritis becomes isolated in her home as her pain increases and she loses strength, endurance, and balance.

Osteoarthritis: a global musculoskeletal disorder

Osteoarthritis, the most common joint disorder, affects over 25 million Americans, leading to a large economic and functional burden on individuals and society . Disability attributable to knee osteoarthritis is equal to that for cardiac disease and greater than that for any other medical condition in the elderly . It is also important to consider the impact of osteoarthritis in younger women. A recent cross-sectional study identified radiographic evidence of hand and knee osteoarthritis in women under age 40, with a higher prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in African-American women (23.1%) compared with that in Caucasian women (8.5%) .

Osteoarthritis is a chronic, degenerative joint disease characterized by focal articular cartilage loss with variable amounts of subchondral bone reaction. It is a disease of the cartilage of weight-bearing joints primarily with “wear and tear” as a presumptive etiology. The articular or hyaline cartilage is composed of collagen (providing strength), chondrocytes (providing viscous synovial fluid for lubrication), and proteoglycans (providing distensibility and hydration). As loads are placed across the joint, cartilage and subchondral bone can be damaged, especially if the joint has an abnormal alignment. This damage leads to loss of adequate proteoglycan synthesis and release of lysosomal proteases that cause further cell death.

The association between physical activity and osteoarthritis has been studied primarily in areas of (1) level of activity, especially sports participation; (2) postinjury osteoarthritis (secondary osteoarthritis); and (3) exercise in managing osteoarthritis. There have been few well-controlled prospective longitudinal studies in these areas. The strongest evidence correlates previous injury with developing osteoarthritis . Studies looking at exercise as treatment for osteoarthritis have shown that exercise can limit the disability associated with osteoarthritis in elderly individuals .

Animal research shows that normal repetitive weight-bearing use of a joint preserves the structure and function of the joint . In vitro studies of chondrocytes have shown that loading in the physiologic range stimulated proteoglycan synthesis and improved flow of nutrients . The articular surfaces of joints demonstrated degeneration when loading was prohibited . Prolonged joint disuse results in structural degeneration of cartilage. Despite these findings, a recent review article evaluating the relationship between physical activity and osteoarthritis prevention concluded that no studies demonstrate direct preventive effects of physical activity on the development of osteoarthritis . A more salient concept for rehabilitation providers is the risk to cartilage if immobilization is prescribed.

Studies have been contradictory in associating level of activity and developing osteoarthritis. Framingham study data were used to evaluate the level of current physical activity and the risk of radiographic, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in older individuals (mean age: 70.1 years; SD: 4.5 years) and demonstrated that current heavy weight-bearing exercise in elderly men and women may increase the risk . Researchers loosely defined heavy weight-bearing exercise as lifting greater than 5 lb, outdoor work with heavy tools, and “other strenuous sports or recreational activity.” The researchers concluded that elderly men and women engaging in greater than 3 h/d of heavy physical activity for many years have an increased risk of knee osteoarthritis. The risk was greatest in subjects with the highest body mass index, demonstrating the link between obesity and osteoarthritis found in other studies . Another study using Framingham data found no increased risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in men or women who engaged in regular physical activity in their middle years . A prospective study of adults correlated self-reported physician diagnosis of osteoarthritis with running greater than 20 miles/wk in men under 50 years old but found no such relationship among older men or women under or over 50 years of age . The general consensus is that runners without underlying lower-extremity biomechanical abnormalities are at no additional risk of developing osteoarthritis .

There has been limited success with defining a dose-response curve between physical activity and osteoarthritis. In addition to time of exposure, factors such as torsional loading and speed of force application are relevant, with slowly applied loads considered better tolerated, perhaps due to damping by muscles . Increased development of osteoarthritis may be associated with sports that involve tortional impacts or apply torsional loads over time, but this has not been specifically defined.

Several risk factors have been identified for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis of the knee, the hand, and possibly the hip is more prevalent in women, especially postmenopausal women, than in men, suggesting that hormonal changes play a role . Researchers concluded that postmenopausal estrogen-replacement therapy might protect against osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women . It is difficult to ascertain whether there are gender differences in how physical activity impacts individuals either in the development or treatment of osteoarthritis. Matching men and women by activity to confirm and identify such a difference has been difficult. In addition, other prevailing factors, including genetic predisposition, equipment use, and quality of performance, may play a significant role in physical activity contributing to osteoarthritis. Obesity has repeatedly been correlated with knee osteoarthritis . Exercise prescription for obese women presents a rehabilitation challenge. Low-impact aerobic activity without torsional loading is likely the best mode of exercise in this population.

Regional musculoskeletal disorders in midlife and older women

Common spinal disorders

Cervical spondylosis

Spondylosis is the term for progressive bony changes of the spine. Spinal degeneration begins with loss of intervertebral disc height, leading to changes in disc and spinal ligaments. Altered patterns of load-bearing in the spine arise with resultant sclerosis of the vertebral body, uncovertebral joints (cervical spine) and zygoapophyseal joints (z-joints), as described in the lumbar spine . While most older persons do not experience symptoms related to spondylosis, symptomatic patients describe axial neck pain, muscle spasm, stiffness, and loss of motion. Cervical radiculopathy (nerve root injury) or cervical myelopathy (spinal cord injury) can result from narrowing due to progressive cervical sclerosis, loss of disc height, and soft tissue changes (disc herniation, ligament hypertrophy). Cervical myelopathy is the most common spinal cord injury at middle age and older . It presents with gradual loss of motor strength and balance with gait dysfunction and fine motor deficits. Cervical radiculopathy (pathologic process affecting the nerve root) in adults affects most commonly, in order, the C7, C6, C8, and then the C5 nerve root with sensory, motor, and reflex involvement based on severity . Pertinent findings on examination include loss of cervical spine range of motion; loss of accessory gliding at the vertebral segments, uncovertebral joints, and zygoapophyseal joints; and loss of flexibility in the muscles of the neck and thorax. Changes in the neurological examination relate to the root level or spinal cord level, if involved, including deficits on manual muscle testing, sensory testing, coordination testing, and reflex testing. In the setting of myelopathy, hyperreflexia may be demonstrated in the lower limbs due to the upper motor neuron lesion. Provocative maneuvers can be used to augment the physical examination of the neurological system. Spurling’s test is done to reproduce discrete radicular symptoms in the lower cervical roots. The examiner places the patient’s cervical spine in ipsilateral lateral flexion and extension and asks about radiating symptoms. If negative, an axial load can be applied through the head with the same query for radiating symptomatology.

Diagnostic testing with plain radiographs is not always necessary or useful as osteophytes may be age-related. Radiographs typically demonstrate the spondylosis described above (osteophytic spurs at the vertebral end-plates, the uncovertebral joints, and the zygoapophyseal joints) and narrowing of the lateral or central foramina. Flexion and extension films are indicated if instability is a consideration. MRI delineates soft tissues, including disc, spinal cord, nerve root, and ligament ( Fig. 2 ). As noted above, disc degeneration is ubiquitous by the eighth decade and care must be taken to corroborate findings on radiographic studies with the patient’s presenting signs and symptoms. CT scan with or without myelography may be clinically useful in individual cases or when other tests are inconclusive. Electrodiagnostic studies (electromyogram, nerve conduction velocity, somatosensory-evoked potentials) can supplement imaging and help to determine acuity of lesions. Laboratory testing is generally normal.

The management of cervical spondylosis is typically nonsurgical. As in other musculoskeletal conditions, pain management is an initial focus. Oral medication, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors, and various analgesics, can be prescribed with close attention to minimizing toxicities, especially in older individuals. Depending on the acuity of symptoms and the patient’s preference, ice or heat can be applied topically. Deeper levels of tissue heating are achieved with therapeutic ultrasound. Therapeutic electrical stimulation modalities are used to stimulate local blood flow and reduce associated muscle spasm. Joint mobilization and stretching are employed and advanced as tolerated by the patient, with a goal of maximizing cervical spine range of motion. Long-standing postural abnormalities (eg, forward head) may not be amenable to significant alteration in older women; younger women are counseled regarding normal posture when posture modification is more likely. Manual therapy to evaluate and treat restricted cervical segments is used and requires a skilled practitioner.

The exercise program is tailored to address flexibility, strength, endurance, and motor-control deficits. Many adults have muscle imbalances with chronically shortened phasic musculature (pectoralis, latissimus dorsi, anterior scalene) and lengthened and weak tonic muscles (trapezius, rhomboids, spinal extensors). Once the imbalances are identified, manual resistance techniques are employed to correct the length/tension relationships. Tactile cueing is frequently necessary to facilitate appropriate co-contraction in the cervicothoracic region. Functional assessment can identify activities of daily living and recreational activity that might be contributing to ongoing abnormal movement patterns. Resting positions and movement patterns can be evaluated ergonomically with recommendations given for adaptation as appropriate.

Interventional procedures, from epidural injections to nucleoplasty, and surgery may be indicated in specific cases, especially in the setting of discogenic or radicular pain. A review of the indications, contraindications, specific procedures, and outcomes of various surgical and interventional procedures are not included in this article.

Thoracic kyphosis

Kyphosis is abnormal curvature in the sagittal plane. Posterior thoracic convexity has been given a normal range of values of 20° to 40° by some investigators, but others have documented a wider range of normal values . As one ages, there is a trend, especially in women, toward increased thoracic kyphosis and reduced lumbar lordosis. Kyphotic deformities that are not compensated for in the spinal segments above and below result in anterior spinal decompensation. Conversely, conditions that compromise the anterior structures (vertebral bodies), such as osteoporosis, infection, or tumor, will promote thoracic kyphotic deformity. Postural kyphosis is a term used to describe a flexible curve with poor carriage of the body. It typically corrects with the spine in extension or the subject in prone . If this poor posture continues as one ages, the curve may become more fixed. There are many other etiologies of kyphosis; a review of these is beyond the scope of this article.

Symptomatic patients initially describe an intermittent achy pain that occurs over the apex of the curve. Women with more extensive curvatures may be at risk of disc disease, facet arthropathy, and foraminal and central stenosis and should be carefully questioned and examined to rule out neurological involvement. A history of neuromuscular disease, trauma, infection, surgery, radiation, or bone disease should be queried, as these can be etiologic factors in the development of kyphosis. Impingement of the rotator cuff tendons can occur in conjunction with the thoracic kyphosis because of limitation in scapular mobility on the thoracic wall. This causes abnormal kinematics of the glenohumeral joint leading to impingement of the rotator cuff tendons in the subacromial space. Physical examination includes observation, palpation to localize the pain, range-of-motion testing, and neurological testing. Compensatory hyperlordosis of the cervical and lumbar spine is expected. Evidence shows that kyphotic curves are larger in women older than 40 years than in men older than 40 . During spinal active range of motion, kyphosis in older woman corrects incompletely with extension. Associated flexibility deficits include tight hamstrings and hip flexors. In patients complaining of associated shoulder pain, a complete examination of the shoulder is indicated to assess scapulothoracic rhythm and rule out rotator-cuff tear. Diagnostic testing starts with posteroanterior and lateral radiographs of the spine. Flexion and extension views should be done if instability is a concern. One investigator found an indirect correlation between bone mineral density and thoracic kyphosis . Bone density testing should be considered in the context of the individual woman’s medical, menstrual, and family history. MRI, bone scan, and CT scans may also be useful in more complex cases, such as a woman presenting with neurological deficits. For treatment suggestions for symptomatic kyphosis, refer to the preceding section on cervical spondylosis. If the curve corrects with prone lying or extension, there is more opportunity for therapeutic exercise that includes stretching and strengthening to affect posture and symptomatology. In patients with associated rotator cuff impingement, muscular reeducation of the scapula can improve scapulothoracic rhythm and should precede rotator cuff strengthening.

Thoracolumbar scoliosis

The incidence of scoliosis, or lateral deviation of the spine, increases with age and affects between 3% and 30% of the population . Scoliosis diagnosed in adults develops before skeletal maturity and is not previously diagnosed or is secondary to bone remodeling issues, such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, postoperative changes, or degenerative changes . In one review, which found that 3.9% of adults had thoracolumbar or lumbar scoliotic curve that developed in adolescence and progressed in adult life, about 60% of the subjects had spinal pain . Idiopathic scoliosis, the most common type of scoliosis, has a much greater incidence in females. It is difficult to correlate pain symptoms with severity of curve; curves less than 20° are typically asymptomatic while curves greater than 60° lead to impairment in the intraabdominal and thoracic organ systems and neurological structures. As with other spinal lesions, the history includes specific questioning on the location, duration, characteristics, and behavior of the pain. Aggravating and relieving factors can assist in identifying the tissue generating pain. The physical examination includes not only a thorough musculoskeletal assessment, but also a detailed neurological exam to rule out radiculopathy. Right thoracic and left lumbar curvature is the usual presentation. Side to side comparison of shoulder heights, inferior angle of scapula, iliac crest, and leg lengths is important. Long-standing curves can cause abnormalities and asymmetry of the pelvis and hips, which must be evaluated and treated. Manual assessment of the spinal segments and provocative maneuvers of the disc and zygoapophyseal joints are included. The examiner should screen for diseases associated with scoliosis. A joint survey should be completed to assess for Marfan’s syndrome. A thorough skin assessment for any stigmata of neurofibromatosis is important. Initial radiographs should include standing posteroanterior and lateral thoracolumbar views ( Fig. 3 ). Serial measurements of the Cobb angle can assess for progression of the curve. MRI can be useful when neurological dysfunction is present. CT scan used in conjunction with myelography can help rule out spinal cord compression. Bone density testing may be indicated in women with risk factors for osteoporosis because women with scoliosis have been shown to have lower bone mass than their peers .