1.8 Evidence-Based Physical Therapy for Stress and Urge Incontinence

What Does “Evidence-Based” Mean?

What Does “Evidence-Based” Mean?

During the 1990s, it was strongly emphasized that all sorts of health care ought to be “evidence-based.” Several definitions of “evidence-based” were introduced, e.g.: “Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” [Sackett et al. 2000]. The authors emphasized that evidence-based medicine is the integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.

In the earlier history of the subject, only a few high-quality research publications were available on physical therapy. Physical therapy practice therefore has a long tradition of being based solely on clinical expertise and patient values. However, several reports based on high-quality research data are now available in most areas of physical therapy, and the best research evidence now needs to be incorporated into clinical decision-making. The World Confederation for Physical Therapy has defined evidence-based practice as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients, integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research” [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2001]. Another definition of evidence-based physical therapy is: “Evidence-based physiotherapy practice has a theoretical body of knowledge, uses the best available scientific evidence in clinical decision making, and uses standardized outcome measures to evaluate the care provided” [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2001].

Clinical effectiveness has been defined as “the extent to which specific clinical interventions, when deployed in the field for a particular patient or population, do what they are intended to do—i.e., maintain and improve health and secure the greatest possible health gain from the available resources” [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2001]. The “6 Rs” of clinical effectiveness were introduced: right person, right thing, right way, right place, right time, and right results.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard design for research to determine the effectiveness of an intervention (does this therapy work, and to what degree does it work?) and comparison of effects between different treatments. The randomized controlled trial is the design that provides the best internal and external validity for answering questions of this type. Internal validity means that we can trust that the effect is due to the intervention (physical therapy) itself and not caused by other changes occurring at the same time. External validity means that we can generalize the results to other patients/clients similar to those investigated. However, there are of course other questions that are important to raise and answer in the field of physical therapy, in addition to whether the intervention works, and physical therapists may wish to raise such questions. However, for each research question there is an optimal research design. For questions of prevalence and diagnosis, cross-sectional studies are needed; for questions of etiology and prognosis, cohort or case–control designs are needed; and for questions on experience and the way in which a person perceives a condition, qualitative research may be the best.

In 1973, Cochrane stated, “It is surely a great criticism of our profession that we have not organized a critical summary, by speciality or subspecialty, adapted periodically, of all randomized controlled trials” [Cochrane 1973]. Later, the Cochrane Foundation was founded, focusing on systematic review as a basis for decision-making in health care.

The hierarchy of strength of evidence for intervention studies is as follows:

- Systematic reviews

- At least one RCT of appropriate size

- Well-designed nonrandomized trials, e.g., cohort, case–control

- Well-designed nonexperimental studies from more than one center

- Opinions—respected authorities based on clinical evidence

Important databases available on the Internet for physical therapists are:

- The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

- The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR)

- The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

- The Cochrane Methodology Register

- PEDro—the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (a combination of all the other databases exclusively concerned with physiotherapy research)

- The National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

- The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database

- Medline/PubMed

- The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

- EMBASE: Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine

- Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED)

- SPORTdiscus.

Physical Therapy and Urinary Incontinence

Physical Therapy and Urinary Incontinence

At the 14th General Meeting of World Confederation of Physical Therapy (WCPT), held in Yokohama in 1999, physical therapy (physiotherapy) was described as “providing services to people and populations to develop, maintain and restore maximum movement and functional ability throughout the lifespan” [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999]. The text continues, “Physical therapy includes the provision of services in circumstances where movement and function are threatened by the process of ageing and injury or disease.” Optimal function of the pelvic floor musculature (PFM) is of vital importance for the ability to live a social and meaningful life, to move, and to be physically active. Dysfunction of the PFM can occur as an idiopathic condition, during pregnancy and after childbirth, after surgery, in connection with neurological disease, because of disuse, or due to aging. Physical therapy is concerned with identifying and maximizing movement potential in the spheres of health promotion, prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999]. It is also stated that physical therapy involves “using knowledge and skills unique to physical therapists” and that it is a service “only provided by, or under the direction and supervision of, a physical therapist.”

The theoretical background for physical therapy is based on thorough knowledge of descriptive and functional anatomy, physiology/exercise physiology, motor control and learning, clinical assessment, and knowledge of methods of facilitating movements, contractions, and relaxation. In addition, health psychology, teaching methods, and ethics are important areas to build on when teaching patients, clients, and healthy groups. The physical therapy process involves assessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation.

Assessment

Assessment

In most countries, the patient meets the physiotherapist after referral by a medical doctor. However, the physiotherapist always takes a thorough history, followed by clinical assessment of the pelvic floor and perineum. To assess the function of the PFM muscles, vaginal palpation and observation of the inward movement of the perineum are of the utmost importance in giving

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

As patients are referred by a medical doctor, a detailed diagnosis with knowledge of the pathophysiology should optimally be the background for the referral. The more information the physiotherapist has from other investigations, the easier it is to set up an intervention plan. However, in real life, many patients come without any urodynamic, gynecological, or pathophysiological investigations. Often, the physiotherapist therefore starts pelvic floor interventions without being aware of the causes of the condition. After taking the patient—s history and carrying out an evaluation, the physiotherapist may conclude that the methods available in physiotherapy are not adequate for the patient concerned. Physiotherapists should make referrals to another agency when physiotherapy is inappropriate [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999].

The pelvic floor muscles are one of many factors contributing to the urethral closure mechanism [Lose 1992]. Other important factors are contraction of smooth and striated muscles within the urethral wall, blood flow, and intact ligaments and fasciae that keep the bladder and urethra in an optimal position during increases in intraabdominal pressure. If factors other than the functioning of the PFM are the cause of incontinence, PFM training may be unsuccessful—for example, if the urethral ligaments are totally ruptured during childbirth. However, since the pelvic floor muscles are untrained in most individuals, training the muscles has a great potential for improvement. Strengthening and improving PFM function is very likely to be able to compensate for other nonfunctioning factors [Lose 1992].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has established a classification system for use in evaluating rehabilitation interventions, know as The International Classification of Impairments, Activities and Participation [ICIDH-2 1997]. Pathophysiology is excluded from this classification. The causes of suboptimal functioning of the PFM— for example, muscle and nerve damage during vaginal birth—can be classified at the pathophysiological level. A nonfunctioning PFM can be classified at the impairment level. The actual leakage and the trouble it causes the individual are at the disability/activities level, and problems in participating in society and quality-of-life issues are at the handicap/participation level. Physical therapy by PFM training will aim to make changes at all of these levels, and the theory underlying strength training is that by improving PFM function, leakage will be stopped or strongly reduced, enabling the patient to function more adequately and enhancing his or her quality of life. A higher cure rate after PFM exercise is expected if the treatment is based on a more precise diagnosis at the pathophysiological level [DeLancey 1996].

Planning

Planning

Planning includes choosing measurable outcome goals negotiated in collaboration with the patient/client, family, or caregiver [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999].

Planning includes choosing measurable outcome goals negotiated in collaboration with the patient/client, family, or caregiver [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999].

Since the patients themselves may have different goals for the treatment, this is extremely important. For some persons with urinary incontinence, the aim is to reduce leakage to an acceptable level, not to be dry on a provocative jumping test. Others are not satisfied even though they have only one drop of leakage during a high-impact aerobic class.

Intervention

Intervention

As the PFM is situated underneath the pelvis, and is rarely used consciously, many women do not know how to contract the muscles. In healthy individuals, the PFM is contracted as an unconscious co-contraction simultaneously with, or before, an increase in intraabdominal pressure. A voluntary contraction probably represents a mass contraction of the three layer muscles that can be described as an inward movement and squeezing around the pelvic openings [Kegel 1952]. A correct PFM contraction does not involve any visible movement of the pelvis or outer part of the body. A correct contraction can be felt by vaginal palpation and observed as a movement of the perineum in a cranial direction. Sub-maximal contractions can be performed in isolation. However, a maximum PFM contraction is probably not possible without co-contraction of the abdominal muscles, particularly the transversus abdominis muscle [B⊘ et al. 1990b]. In thin individuals, this can be observed as a tiny dorsal movement of the abdomen, with no movement of the pelvis.

Several studies have shown that approximately 30% of women do not contract correctly at their first consultation, even after thorough individual instruction [Benvenuti et al. 1987, B⊘ et al. 1988, Hesse et al. 1990]. The most common errors are to contract the outer pelvic muscles instead—e.g., the abdominal, hip adductor, and gluteal muscles. Bump et al. [1991] showed that 25% were straining instead of contracting and that after verbal instruction, only 49% were able to contract the PFM in a way that increased urethral pressure. If the patient is not able to contract, the physiotherapist can use different techniques based on proprioception and exteroception—e. g., massage, stretching, or electrical stimulation. However, most women learn how to contract very quickly. In a study by B⊘ et al. [1990a], only four of 52 women were unable to learn to contract correctly during a 6-month period. Although some women have problems in learning to contract the PFM, it is important to emphasize that 70% are able to contract at the first consultation. Only a few patients therefore need manual techniques and electrical stimulation after the first consultation. The aim of the first consultations is to help the patient search, find, and control PFM function. When the patient is able to contract, the actual training of the muscles starts. The physiotherapist can choose between training with or without biofeedback. Based on the patient—s diagnosis and problems, one can train the PFM in order to improve muscle strength and endurance, coordination and motor control, body awareness, and relaxation, or one can simply provide the patient with pads or preventative devices, depending on each patient—s problems and goals.

The intervention should ideally be selected on the basis of knowledge of the pathophysiology (which unfortunately is almost never available), theory—e.g., exercise science, motor control and learning—and the results of high-quality RCTs, if available. In addition, the physiotherapist has knowledge of general muscular, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases and dysfunctions, and can set up training programs to help patients if they have other problems as well—e.g., in walking.

An important area of intervention in physiotherapy stated by the WCPT document is prevention of impairments, disability, and injury, including promotion and maintenance of health, quality of life, and fitness in all ages and populations [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999]. With regard to the pelvic floor, physiotherapists have put considerable efforts into preventive measures during pregnancy and after childbirth [Noble 1988, Polden and Mantle 1990].

Evaluation

Evaluation

The WCPT emphasizes that physiotherapists should use the same outcome variables before and after treatment in clinical practice [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999]. To date, there is no consensus regarding which outcome measure should be chosen as the most reproducible, responsive, and valid method for assessing urinary incontinence. However, it has been recommended that both women—s reports and measurements of urinary leakage should be used together [Blaivas et al. 1997]. According to the ICIDH, published by the World Health Organization, MRI and ultrasound may be used for measurement in the future at the pathophysiological level. PFM squeeze pressure, EMG, MRI, and ultrasound are methods that can be used to measure impairment. Leakage episodes, leakage index, pad tests, and stress cough tests are methods for measurement at the disability/activities level, and several validated quality-of-life questionnaires can be used to measure at the handicap/participation level. Many of these measurement methods are not available in physiotherapy clinics today. Teamwork with urologists, gynecologists, and neurologists is therefore of the utmost importance to make physical therapy practice more evidence-based [Berghmans et al. 1998a].

In addition, the WCPT addresses the importance of using terminology that is widely understood and adequately defined, and of recognizing internationally accepted models and definitions. In this field, this means following the terminology recommendations of international committees on standardization, as well as those of the WHO, WCPT, and movement science, including exercise science. Finally, the WCPT emphasizes the need for practice to be evidence-based whenever possible, and regards the interdependence of practice, research, and education within the profession as being fundamentally important [World Confederation for Physical Therapy 1999].

Effect of Physical Therapy for Stress and Urge Incontinence

Effect of Physical Therapy for Stress and Urge Incontinence

This review is based on randomized controlled trials. Systematic reviews [B⊘ 1996, 1998, B⊘ and Maanum 1996, Berghmans et al. 1998b, Wilson et al. 1999, Berghmans et al. 2000, B⊘ and Berghmans 2000, Hay-Smith et al. 2001], including one Cochrane review [Hay-Smith et al. 2001], are available in this field, and these have been used for selection of studies. One of the largest published studies on postpartum training is a matched-pair controlled study. This is also included. In contrast to the Cochrane review, which includes a mixture of studies including stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urge incontinence, and mixed incontinence, the present review has classified studies according to diagnoses of either SUI (including SUI based on both history and urodynamic assessment) or urge incontinence, and considers the results separately for each condition. Physical therapy includes PFM training with or without biofeedback, electrical stimulation, and cones, or a combination of these methods.

Female Stress Urinary Incontinence

Female Stress Urinary Incontinence

PFM Training

The aims of pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence are to build muscle strength and power in order to:

- Build a structural support (anatomic location of the muscles, proper attachment, tone, hypertrophy) for the bladder and the urethra.

- Prevent descent of the bladder neck and urethra and close the urethra during abrupt increases in intraabdominal pressure by an automatic, fast and, strong PFM contraction.

- Make individuals able to contract voluntarily with sufficient strength and power to close the urethra before an increase in intraabdominal pressure.

The last point has formed part of PFM training in clinical physiotherapy practice for many years. Miller et al. [1998] showed that teaching women how to contract and teaching them how to contract before sneezing, coughing, and lifting significantly reduced urinary leakage within a week. This should therefore be recommended in all PFM exercise regimens. However, in continent individuals, the PFM contraction is an automatic response without conscious voluntary contraction before activity. In addition, precontractions of this type are only possible before single bouts of physical exertion (for instance, sneezing). Nobody can run or dance over a longer period of time and contract the PFM voluntarily all the time. The main goal of PFM training is therefore to build up the muscles to reach the automatic response level.

Kegel [1948] was the first to report that pelvic floor muscle exercises were effective in treating urinary incontinence in women. In uncontrolled studies, he reported an 84% cure rate in a variety of incontinence types. Since then, several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that PFM exercise is more effective in patients with SUI than no treatment [Henalla et al. 1989, Hofbauer et al. 1990, Lagro-Janssen et al. 1991, B⊘ et al. 1999].

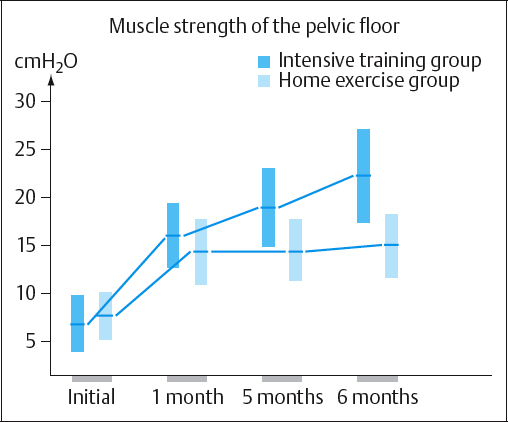

Due to the different outcome measures and instruments used to measure PFM function, it is impossible to compare results between studies, and it is impossible to conclude which training regimen is more effective. B⊘ et al. [1990a] showed that instruction followed by training was significantly more effective than home exercises. The authors combined individual assessment and teaching of correct contraction with strength training in groups [B⊘ et al. 1990a, 1999]. Strength training in groups is motivating both for the participants and the therapist. It is cost-effective and time-effective, and training that is beneficial for general health can be incorporated into the program (e. g., strength training of the abdominal, back, and thigh muscles, relaxation, lifting techniques, and cardiovascular training). However, it has to been based on individual teaching of correct contraction. In the study by B⊘ et al. [1990a], there was a huge difference in the strength increase in favor of patients who had exercised in groups with a physical therapist in comparison with the home training group (Fig. 1.74). A significant reduction in urinary leakage, measured by pad testing with a standardized bladder volume, was only demonstrated in the intensive exercise group (Fig. 1.75). In addition, the percentages of patients who were continent or almost continent were 60 % and 17% in the exercise group and home training group, respectively. This study demonstrated that huge differences in outcome can be expected in relation to the intensity and follow-up of the training program, and very little effect can be expected after training without close follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree