Fig. 28.1

(a) Three segments of flexor retinaculum. H hamate hook, T trapezium, P pisiform, S scaphoid, FCU flexor carpi ulnaris, FCR flexor carpi radialis. 1: proximal, 2: middle, true transverse carpal ligament, 3: distal aponeurotic portion of the flexor retinaculum. (b) partial release of the flexor retinaculum. (c) Complete release of the flexor retinaculum. K wires are shown in hamate hook and trapezium [Reprinted from Cobb TK, Cooney WP. Significance of Incomplete Release of the Distal Portion of the Flexor Retinaculum. J Hand Surg Br. 1994; 19: 283–285. With permission from Sage Publications]

Hook of the Hamate

There is an increased risk of neuropraxia with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. This can be minimized by hugging the ulnar aspect of the carpal canal with the endoscopic instrument. In order to do this effectively and provide for a straight line of pull it is important to place the skin incision in relation to the hook of the hamate. Unfortunately, the hook of the hamate can be difficult to palpate and the use of Kaplan’s cardinal line is unreliable. Based on an anatomic study [5] the hook of the hamate can be reliably localized with the technique demonstrated in Fig. 28.2.

Fig. 28.2

The pisiform is palpated. A line is drawn from this point to the proximal palmar crease at the level of the central aspect of the index finger. A second line is drawn from the central portion at the base of the ring finger to the distal flexor crease of the wrist at the junction of the middle and ulnar thirds. The junction of these two lines marks the location of the hook of the hamate [Reprinted Cobb TK, Cooney WP, An K. Clinical location of Hook of Hamate: A technical Note for Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release. J Hand Surg Am. 1994; 19: 516-518. With permission from Elsevier]

Palmar Fascia

Palmar displacement of the flexor tendons after release of the transverse carpal ligament (Bowstringing) has been implicated as a cause for weakness after carpal tunnel surgery. In fact step cut lengthening of the transverse carpal ligament has been advocated to prevent this [6]. The majority of the palmar fascia is not divided with endoscopic carpal tunnel release which provides an uninjured natural tissue barrier to bowstringing.

Transligamentous Branch of the Median Nerve

The recurrent motor branch of the median nerve passes around the distal edge of the TCL in most cases. It also can pass through the ligament in up to 23 % of cases which causes challenges with both open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release [7]. Fortunately, the nerve rarely arises from the ulnar aspect of the median nerve and is therefore rarely encountered. This underscores another important reason to hug the ulnar aspect of the canal when performing endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Anatomic variations such as a persistent median artery or aberrant muscle tendon relationships and dimpling of the TCL should alert the surgeon to the presence of a transligamentous branch. Dealing with a transligamentous branch safely, for both open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release, is about visualization. Therefore the presence of a transligamentous branch does not necessarily preclude accomplishing the procedure (Fig. 28.3).

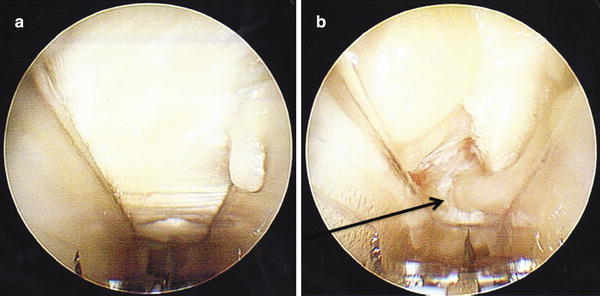

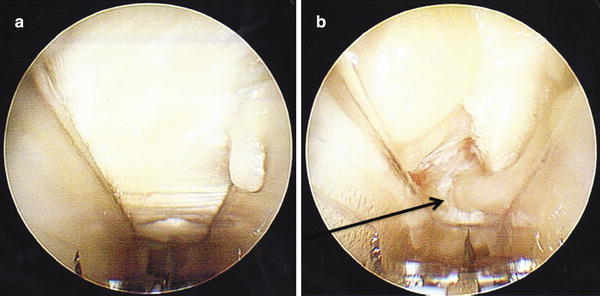

Fig. 28.3

(a) Endoscopic view showing a dimple in the distal 1/3 of the transverse carpal ligament. There is a small synovial frond on the right. (b) Post-division of the TCL. Arrow locates the transligamentous branch of the median nerve

Glabrous Skin

Glabrous skin (palm of hands and sole of feet) is unique in that it has no hair follicles and it is highly innervated. One of the distinct advantages of the single incision approach to endoscopic carpal tunnel release is the ability to place the incision outside of the glabrous skin, avoiding the associated morbidity and potential wound complications. This advantage is lost with the two incision endoscopic technique. Additionally the two incision technique is fraught with a higher complication rate [8].

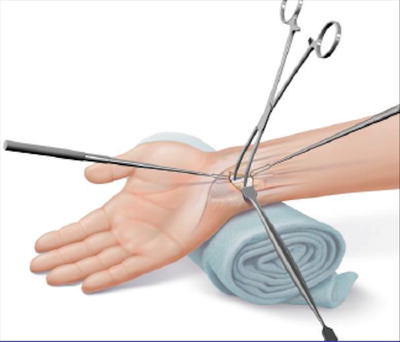

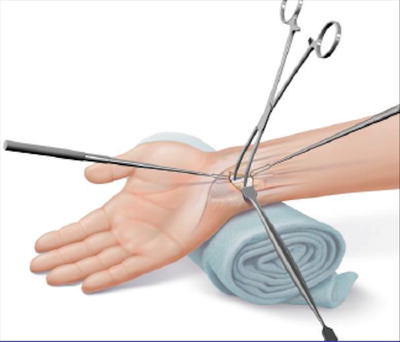

Exposure

The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table with the arm abducted on a hand table. It is useful to place the hand palm up in a holder or over a surgical towel so that the wrist is extended 15–20° (Fig. 28.4). The hand, wrist, forearm, and the arm proximal to the elbow should be completely exsanguinated using an Esmark bandage. The tourniquet is then elevated to create a bloodless field. The surgeon’s hand, when holding the instrument, should naturally align the blade assembly so that it points axially from the ulnar side of the carpal tunnel to the base of the ring finger. This course is anatomically optimal for avoiding injury to the median nerve. Right-handed surgeons will usually prefer a position in the axilla for a right carpal tunnel release and cephalic position for a left release. It is vice versa for left-handed surgeons. The surgeon should be able to easily view the monitor over the assistant’s right or left shoulder. General or regional anesthesia is advised so that visualization is not obscured by a carpal canal full of anesthetic fluid.

Fig. 28.4

Patient positioning [Reprinted from Centerline Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release: Surgical Technique. Arthrex, Inc.; 2010. With permission from Arthrex, Inc.]

The surgical incision is placed transversely in or near one of the wrist flexion creases (usually the proximal) between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the palmaris longus (PL) (Fig. 28.5). If the patient does not have a PL, the radial extent of the incision should be 2 cm ulnar to the flexor carpi ulnaris. The incision is usually 2 cm in length. Veins that cross the incision are coagulated with a bipolar and divided. Placement of the skin incision and the position of the hook of the hamate will set the trajectory of the endoscopic device. Therefore it is advisable to mark out the hook of the hamate, at least initially, as a surgeon is becoming comfortable with placement of the incision.

Fig. 28.5

Incision [Reprinted from Centerline Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release: Surgical Technique. Arthrex, Inc.; 2010. With permission from Arthrex, Inc.]

The soft tissue dissection is started on the radial aspect of the incision and taken directly down to the antebrachial fascia. In this location the flexor retinaculum is closely adherent to the antebrachial fascia. As you move medial and lateral from the center these tissues divide and it is much easier to get out of the proper plane of dissection [9] (Fig. 28.6). This dissection is then swept in an ulnar direction. This method reveals a consistent plane that mobilizes Guyon’s canal contents, allowing for their retraction out of harm’s way. During this portion of the procedure, fascial bands are often encountered that may inhibit the mobilization of these tissues.