Chapter 11 Electrodiagnostic Medicine III

Case Studies

The electromyographer tailors the EDX study based on the history and physical examination. A differential diagnosis is developed before the study that considers disease processes involving multiple levels of the central and peripheral nervous system. A deductive process is used in which each NCS and muscle examined with needle EMG should assist with narrowing the differential diagnosis until a conclusion is reached. This dynamic (rather than protocol or rote) process for the selection of nerves and muscles to study is more likely to ultimately provide an accurate diagnosis, helps limit the number of studies to the minimum required for the diagnosis, is required by the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine guidelines, is required by the Current Procedural Terminology code used for billing these studies, and is the standard of practice.3

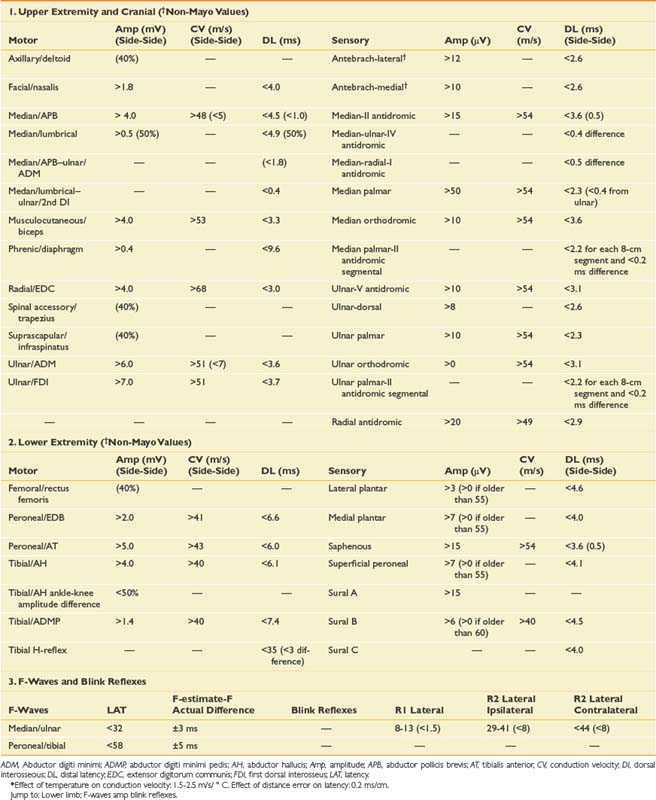

This chapter reviews a series of cases to illustrate a logical approach to the neurophysiologic workup of various clinical complaints. In clinical practice each case is unique, however, and will vary from patient to patient and clinician to clinician. The specific testing must be individualized based initially on the presenting complaint; however, during the study, the procedure changes based on the data obtained from initial NCS or needle EMG findings. Specific testing performed also depends on patient tolerance and other factors such as anticoagulation status; the presence of lymphedema, central lines, or pacemakers; and patient positioning. The cases reported below demonstrate how to apply the basic science and techniques described in Chapters 9 and 10 to a clinical situation. The EMG findings in the following cases are graded using the Mayo Clinic rating scale (Box 11-1).9 Insertional activity is described as increased if there is anything more than minimal electrical noise generated by the electrode movement itself. This can include positive waves, fibrillation potentials, myotonic discharges, myokymia, neuromyotonia, or the “snap-crackle-pop” insertional activity seen in some normal subjects. Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves are interpreted the same in our laboratory, both representing active or uncompensated denervation, which is reflected on the tables in a single column referred to as fibrillation potentials. The grading of fibrillation potentials, fasciculation potentials, and voluntary MUPs is otherwise defined in Box 11-1. Normative data for NCSs (based on the Mayo Clinic EMG laboratory database) are provided in Table 11-1.

BOX 11-1 EMG Grading Guidelines (Mayo Clinic EMG Reports)

Spontaneous Activity

Polyphasic (graded as % of all MUPs assessed that have >4 phases, rounded to the nearest whole number of the following choices: 15%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%)

Case 1: Upper Limb Paresthesia and Pain

A 45-year-old, right-handed female secretary presents with pain and aching in her right hand that wakes her from sleep and prevents her from typing for more than 5 to 10 minutes. She describes a pins-and-needles sensation in all five digits of her right hand, but on specific questioning admits there are also mild symptoms in the left hand. When the symptoms are severe, she feels pain throughout her entire hand, forearm, and arm as far as the shoulder. These symptoms have been present and getting gradually worse for at least 6 months. She also feels her right hand is weak, as she is dropping objects and is more clumsy than usual. She reports chronic neck pain that seems to be most problematic toward the end of the workday.

Differential Diagnosis

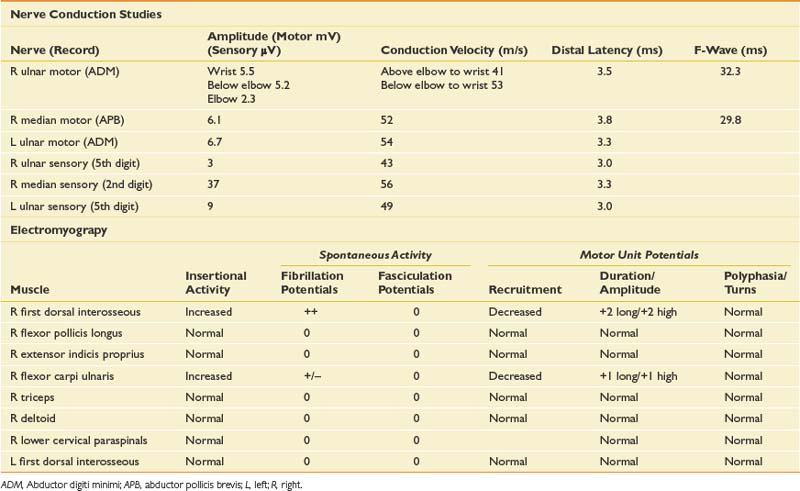

When evaluating for a mononeuropathy, it is helpful to consider the potential etiologies because this will determine which EDX studies should be performed. Although focal compression, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, is by far the most common etiology for a mononeuropathy, a more generalized process involving multiple nerves (e.g., mononeuritis multiplex, hereditary neuropathy with tendency to pressure palsies, multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block) needs to be considered. Cervical radiculopathy is also high on the list of differential diagnoses, and as she reports paresthesias throughout the entire hand, this could reflect involvement of the C6, C7, and/or C8 nerve roots. The NCS and needle EMG findings for this case are shown in Table 11-2.

Discussion

Given the differential diagnosis outlined above, it is important to perform median and ulnar motor and sensory NCSs. A median F-wave was also performed because this may be prolonged where proximal slowing is present, such as in radiculopathy. When median neuropathy at the wrist (carpal tunnel syndrome) is a clinical consideration, we perform the median motor study first and then determine the most appropriate median sensory study based on the motor results. If the motor study is normal, as it was on the left, there are a number of different orthodromic or antidromic sensory studies that can be performed. We chose the orthodromic palmar sensory study on the left because it is one of the most sensitive techniques available and can be abnormal in cases of very mild median neuropathy.29 Other options include radial-to-median distal latency comparison recording from the thumb, ulnar-to-median distal latency comparison recording from the fourth digit, or antidromic median sensory studies recorded from the most symptomatic digit.29 If the motor distal latency is prolonged, a less sensitive but technically less challenging study such as a median antidromic sensory study would be appropriate, and that was the choice on the right. The ulnar sensory response must also be obtained to ensure there is not evidence for a more generalized process. In this case, the NCSs show evidence of a median neuropathy at the wrist, bilaterally, with focal slowing demonstrated by prolonged median motor and antidromic sensory latencies on the right, and relative prolongation of the orthodromic median palmar sensory distal latency on the left, compared with the ulnar response (with a difference greater than 0.3 ms considered abnormal).29

Since the NCSs have confirmed the presence of a median neuropathy at the wrist, the purpose of the needle examination in this case is threefold: (1) to confirm the level of the median nerve lesion, (2) to provide additional information regarding severity, and (3) to exclude a superimposed process that could be contributing to the presenting symptoms, such as cervical radiculopathy. Examining a median-innervated thenar muscle provides the information on severity; in this case the finding of long-duration MUPs and some fibrillation potentials provides further evidence that this is a relatively severe lesion. Examining the pronator teres is helpful because this is a more proximal median-innervated muscle, and if normal, helps exclude a more proximal median neuropathy. Additionally, as the pronator teres is innervated by the C6 and C7 roots, a normal examination helps exclude a cervical radiculopathy at those levels. The deltoid also assesses for C5 and C6 root involvement, which can lead to similar symptoms. Examining the first dorsal interosseous helps exclude an ulnar neuropathy (unlikely given the normal ulnar NCS), but also excludes a C8 radiculopathy or lower trunk plexopathy as a cause for the abnormal findings in the abductor pollicis brevis muscle. Cervical paraspinal muscles were not examined in this case because all the findings on both NCSs and needle EMG pointed to carpal tunnel syndrome. However, if there is a strong clinical suspicion for recent-onset cervical radiculopathy, the paraspinals should be examined because they are often the first muscle to show changes on needle EMG.

Although the diagnosis in this case is bilateral median neuropathy at the wrist, consistent with carpal tunnel syndrome, the presentation highlights that many patients do not describe classic symptoms, and one must consider a broad differential diagnosis in such cases. In carpal tunnel syndrome, more than 50% of patients report sensory symptoms outside the median nerve distribution,30 and this is a reason that EDX examination is critical in refining the clinical impression.

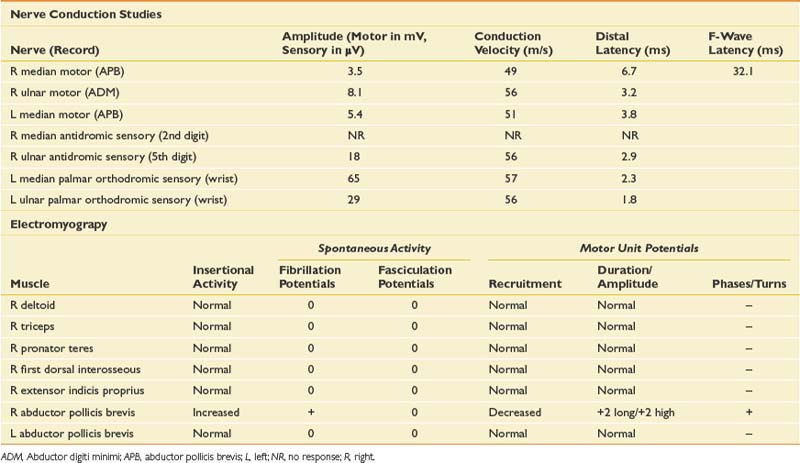

Case 2: Aching and Numbness of the Left Thumb, Index Finger, and Middle Finger

Differential Diagnosis

This is a very common referral to the electromyographer with the primary differential diagnosis being a cervical radiculopathy, median neuropathy at the wrist or myofascial syndrome. A brachial plexopathy is possible but unlikely in the absence of trauma or a history of carcinoma. Although an idiopathic brachial plexopathy (Parsonage-Turner syndrome) could present spontaneously, the pattern of pain and weakness would be unusual. The sensory findings confirmed on clinical examination would argue against a myofascial process and narrow the diagnosis. The pattern of sensory loss could be seen with either a median neuropathy or cervical radiculopathy, but the mild triceps weakness and reflex changes would certainly argue for a radiculopathy, most likely in the C7 distribution. Given the triceps and finger extensor weakness, a radial neuropathy would also need to be excluded with the EDX evaluation. NCSs and needle EMG were performed (Table 11-3).

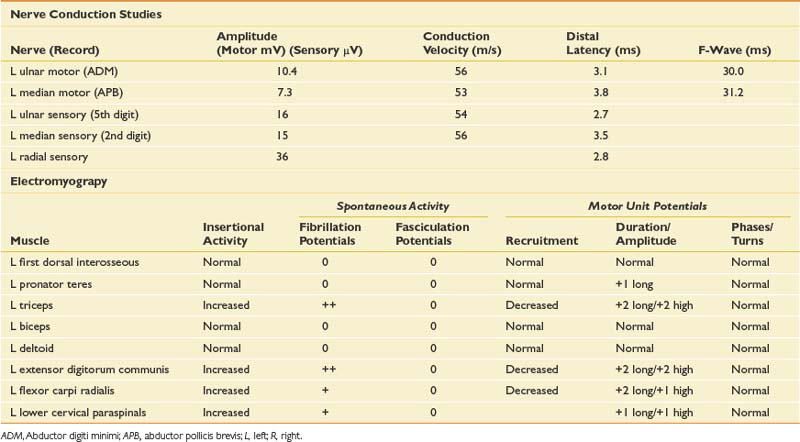

Case 3: Shoulder Pain and Weakness

A 54-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer, status post right modified mastectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy 5 years previously, presents with a 4-week history of right shoulder pain and weakness as well as numbness in the right hand and forearm. She is otherwise healthy and has not been taking any medications except tamoxifen since completing chemotherapy. She denies previous episodes of similar symptoms, nor any history of neck or shoulder trauma. She had recently increased her activity with involvement in a weightlifting program, and had noted some generalized muscle aching in association with that. She states the pain came on suddenly during the night approximately 6 weeks previously with a severe burning and at times deep aching sensation, preventing her from sleeping. The severe pain lasted about 10 days and has now significantly improved, but as the pain improved, she noticed significant weakness that has persisted, such that she can barely lift her arm from her side. She still has good use of her hand.

Differential Diagnosis

Given the history, an infiltrative plexopathy caused by breast carcinoma would be of primary concern; however, the sudden onset of symptoms would argue for an inflammatory/idiopathic brachial plexopathy. In this case a radiation-induced injury should also be considered, but the acute and painful onset would also make this less likely. The finding of myokymia on needle examination is very helpful in such cases, because this is much more frequently found in radiation plexopathy than in cases of metastatic infiltration of the plexus.15,19 The NCSs and needle EMG for this patient are listed in Table 11-4.

Discussion

NCSs in this case show low-amplitude median antidromic and absent lateral antebrachial cutaneous sensory responses, which implies that the lesion is distal to the dorsal root ganglion at the level of the plexus or peripheral nerve. The normal median motor response (C8, T1, lower trunk) in the presence of a low-amplitude median sensory response (C6, C7, middle trunk) suggests the lesion is proximal to the median nerve and at the level of the plexus. The median sensory response on the left is mildly low amplitude with a prolonged distal latency, most likely representing a preexisting median neuropathy at the wrist of the type seen in carpal tunnel syndrome. The musculocutaneous compound muscle action potential (CMAP) is absent on the right but easily elicited on the left. This study was performed because the more easily obtained median and ulnar motor studies are both derived from C8–T1 axons and therefore are spared in this case.

The needle EMG findings, when taken in combination with the NCS results, are most consistent with a severe right upper, and to a lesser extent, middle trunk brachial plexopathy, with evidence to suggest mild cervical root involvement also. Given the somewhat patchy nature of the needle EMG findings, the absence of trauma, and the classic history of severe pain at onset followed by weakness that persists, the cause is almost certainly inflammatory and is typical of neuralgic amyotrophy or Parsonage-Turner syndrome.32 Often a particular peripheral nerve will be severely involved. For example, patients can present with sudden onset of severe dyspnea that is worse when recumbent, because of involvement of the phrenic nerve. They can also present with a classic anterior interosseous neuropathy with weakness only involving the flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus to the second and third digits, and the pronator quadratus. Such cases are frequently misdiagnosed as entrapment neuropathy. Therefore it is critical when evaluating such cases to perform a careful needle examination, looking for patchy involvement outside the muscles that are clearly involved clinically. This includes a search for subclinical contralateral limb involvement, to avoid unnecessary surgery in such cases. A careful history should quickly alert the electromyographer to the likely diagnosis in such cases. Imaging of the cervical spine in this setting can be helpful in excluding a compressive process, but care should be taken to not assign clinical significance to mild spondylotic changes. Imaging of the brachial plexus can also reveal signal abnormalities, and in this case it would also be indicated to exclude an infiltrative process.

Case 4: Hand Numbness and Weakness

Differential Diagnosis

The patient presents with numbness and tingling in a right ulnar nerve distribution and weakness of intrinsic hand muscles. Given the history of compression, the most likely cause for these symptoms would be mononeuropathy involving the ulnar nerve at the wrist or elbow. Such symptoms could also represent a more generalized process such as a hereditary neuropathy with a tendency to pressure palsies, or mononeuritis multiplex (typically the latter would be painful). Other considerations should include lower trunk or medial cord brachial plexopathy and C8/T1 radiculopathy. Anterior horn cell disease involving the lower cervical cord is unlikely given the sensory symptoms. Rarely a spinal cord lesion such as a syrinx or a cortical infarct might present in this way. NCS and needle EMG findings for this case are shown in Table 11-5.

Discussion

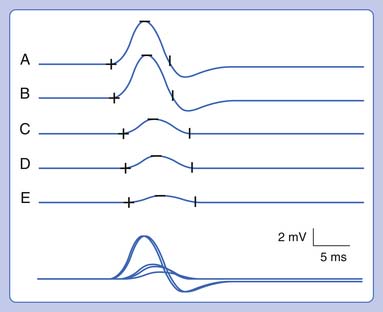

NCSs showed a low-amplitude ulnar motor response on the right, with slowed conduction velocity and borderline distal latency. There was a significant reduction in the CMAP amplitude between the elbow and wrist stimulation sites suggesting a conduction block. This was confirmed with stimulation at the below-elbow site, followed by short-segment stimulation (inching) between the elbow and below-elbow sites (Figure 11-1). There was also significant slowing localized to the elbow segment (evident as a conduction velocity in the above-elbow to wrist segment that was more than 10 ms slower than the conduction velocity of the below-elbow to wrist segment). The left ulnar motor response was normal but the ulnar sensory response was low amplitude with a slowed conduction velocity. With normal median motor and sensory studies on the right, these findings are most suggestive of bilateral ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, more pronounced on the right.

Ulnar neuropathies are relatively common, generally presenting with varying degrees of sensory symptoms in the fourth and fifth digits as well as weakness of ulnar-innervated hand and sometimes forearm muscles. Sensory fibers are usually the most vulnerable and can show abnormalities in very mild neuropathies. Motor responses can be recorded from both the abductor digiti minimi and first dorsal interosseous muscles to improve sensitivity, as a normal response can be obtained from one of the muscles or the other because of the fascicular nature of nerve topography. The diagnosis of a focal ulnar neuropathy at the elbow is suspected with slowing across the elbow segment of greater than 10 m/s compared with the below-elbow segment, of if there is an amplitude drop of 20% over a 10-cm segment. If a question remains, sequential 2-cm stimulation across the elbow can confirm an ulnar neuropathy if there is a 10% drop over a 2-cm segment or a latency difference of greater than 0.7 ms.4,5 An incidental median-to-ulnar crossover in the forearm can simulate an ulnar neuropathy and should always be excluded, particularly if there appears to be a conduction block in the forearm.

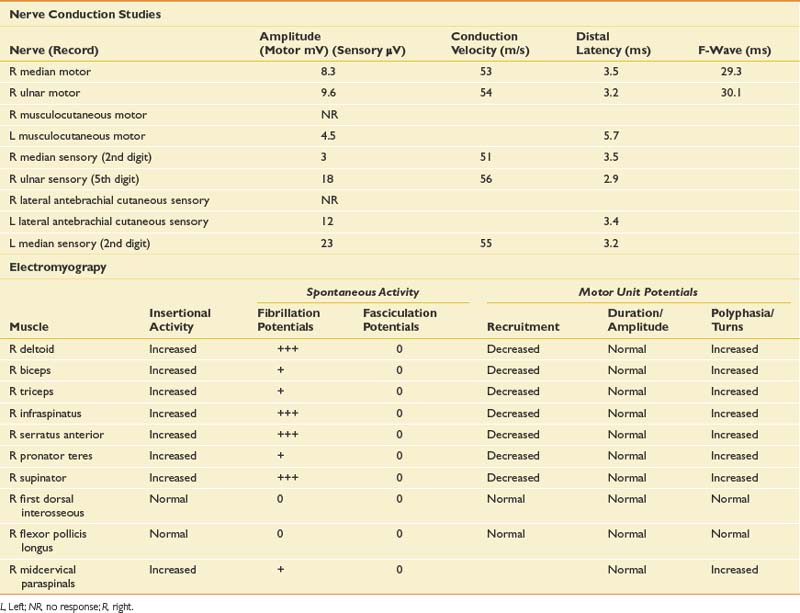

Case 5: Painless Weakness

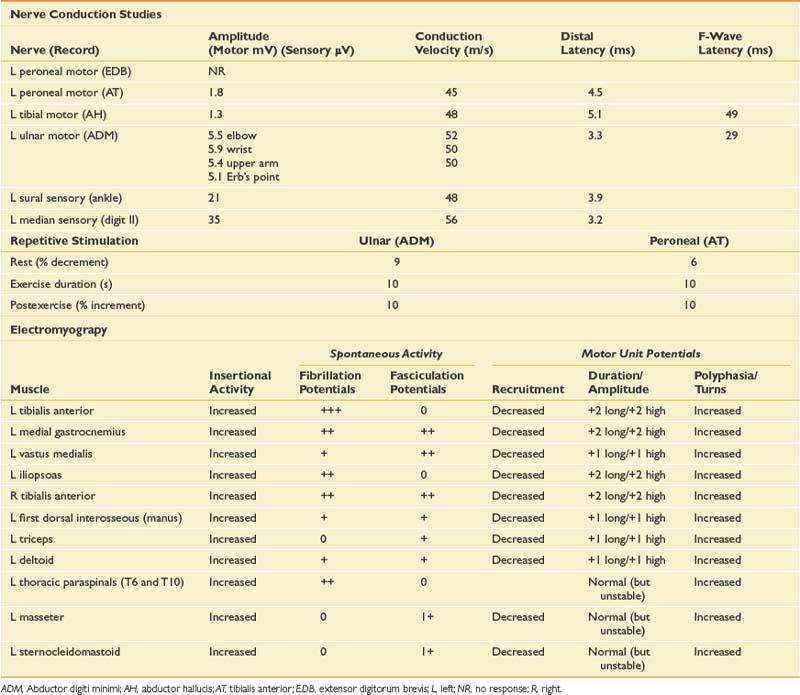

On examination, he has an obvious foot drop when ambulating, atrophy of the left calf, and some fasciculations noted at rest in the gastrocnemius muscle, as well as rare fasciculation potentials in the triceps. Strength testing reveals moderate weakness of the left ankle dorsiflexors, plantar flexors, toe flexors and extensors, and mild weakness of the proximal left lower limb muscles. In the right lower limb, he has mild weakness of the ankle dorsiflexors and toe extensors. Strength is normal in the upper limbs, and sensation is intact throughout. Reflexes are diffusely brisk but symmetric. Plantar responses are downgoing on the right and equivocal on the left. Cranial nerve examination is normal.

Differential Diagnosis

When a patient presents with progressive, painless weakness, one must always consider the possibility of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), particularly when muscle stretch reflexes are normal or hyperreflexic in the presence of lower motor neuron weakness. Other causes for painless weakness include multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block (MMNCB), which initially presents with weakness in a single peripheral nerve distribution, but progresses to involve multiple nerves. In early MMNCB, muscle bulk is typically preserved in the face of significant weakness, but with time patients develop axon loss with associated muscle atrophy and loss of reflexes. Reflexes would generally be reduced in the affected distribution as well. A lumbar plexopathy could explain the left lower limb weakness particularly given the history of mild sensory symptoms. In some cases of infiltrative or inflammatory etiology, bilateral involvement of the plexus can be seen. Although unusual in the absence of pain, multiple lumbosacral radiculopathies should be considered, particularly in the setting of diabetes, or as in this case with a background history of low back pain. When hyperreflexia is present, cervical or thoracic stenosis or intramedullary lesions are a possible explanation for brisk reflexes in an otherwise lower motor neuron problem at the level of the lumbar spine. Some myopathies can present with predominantly lower limb weakness; side-to-side asymmetry is common in inclusion body myositis, in which there is typically early involvement of the quadriceps and ankle dorsiflexors. His young age would generally argue against this. Inherited myopathies such as limb girdle dystrophy could also present with lower limb weakness and some asymmetry. Neuromuscular junction disease such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome should be considered, but there is typically prominent proximal weakness with a fatigable component, depressed muscle stretch reflexes, and autonomic symptoms such as dry mouth. The NCS and EMG findings are presented in Table 11-6.

Discussion

ALS is a disorder of the anterior horn cell that presents with progressive, painless weakness combined with upper motor neuron findings and the absence of sensory symptoms. It is an almost universally fatal disease, with an average life span from the time of diagnosis of 3 to 5 years.28 Other disease processes that could potentially masquerade as ALS, such as polyradiculopathy, polyradiculoneuropathy, or MMNCB, must be entirely excluded because they can have treatment implications. EDX testing is helpful to confirm the diagnosis when it is clinically apparent, and to diagnose the condition when it is clinically suspected but too early to diagnose on clinical grounds alone (abnormal findings are usually present on needle examination long before they become clinically evident).

In ALS, the needle examination typically shows profuse fibrillation and fasciculation potentials, and very complex (polyphasic), unstable MUPs. These findings must be present in at least three different spinal segments (e.g., an upper and lower limb, and thoracic paraspinal muscles), or two spinal segments in combination with bulbar muscles. Within those segments, two or more muscles with different segmental and peripheral nerve innervation must be affected before one can confidently conclude that a progressive motor neuron disease is present (this grading scale is based on the El Escorial criteria for possible or probable ALS).7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree