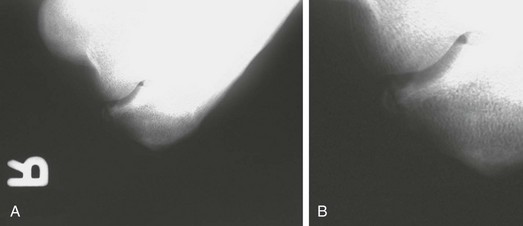

Chapter 43 Athletic activities can lead to elbow inflammation and synovitis, joint degeneration, and formation of spurs and loose bodies. In fact, loose body removal represents the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy in this population.1 Several of the conditions listed are specifically caused by the stress an athlete places on the elbow. Secondary to the high demands on an overhead athlete’s elbow, a relatively small but acute deficit in range of motion (ROM) can be extremely disabling. With chronic motion loss, however, the athlete can adapt with greater ease. The necessary ROM varies with each sport, position, and the individual mechanics required to remain competitive. Posteromedial impingement results from forces at the elbow that begin during late cocking and continue through acceleration and deceleration.2 Valgus extension overload results in shear forces in the posterior elbow, whereas the anterior compartment experiences a tension force medially, with a compression force laterally.3,4 Subsequent chondral changes to the olecranon and distal humerus are observed. With continuation of the offending activity, osteophyte formation typically occurs in the posteromedial elbow. Persistent throwing can cause osteophyte fracture and loose body formation.4,5 Clinically, the athlete has pain and decreased ROM. Similar to acute and chronic elbow injuries, synovial disorders may secondarily result in pain and mechanical symptoms that can hinder an athlete’s performance. Diseases such as synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, and inflamed synovial plica can produce mechanical symptoms that alter normal elbow motion.6–8 These conditions must not be overlooked, and the clinician should maintain a broad differential diagnosis because the athlete’s symptoms may not be secondary to the activity, but rather intensified by the activity. • Insidious and progressive posterior elbow pain and limited elbow extension result from impinging posterior osteophytes; popping, locking, or catching suggests loose bodies. • Symptoms are usually most prominent during the involved activity; the patient is often asymptomatic at rest. • Specific timing of pain exacerbation during the activity can be revealing. Pain in late innings during pitching can indicate ligamentous disease often unmasked after forearm muscles fatigue, whereas arthrosis manifests more frequently with pain and stiffness early in the morning or early in the activity. • Specific timing of pain during the throwing motion itself can help differentiate between ligamentous injury (often most symptomatic during early acceleration) and impingement (which typically produces pain at ball release or follow-through).1,9 • The patient may report intermittent swelling after activity. • Paresthesias may result from ulnar nerve irritation from either impinging spurs or traction during throwing. • ROM, loss of extension: Posterior olecranon spur, posterior compartment loose bodies, bridging osteophyte across olecranon fossa, anterior capsule contracture, collateral ligament contracture with or without ossification. • ROM, loss of flexion: Coronoid spur, anterior compartment loose bodies, coronoid fossa spur, posterior capsule contracture or triceps adhesions, collateral ligament contracture. • Palpation, with or without joint effusion, warmth, or crepitation: Medial, lateral or posterior tenderness can be associated with medial or lateral epicondylitis, triceps tendonitis, or an olecranon stress fracture; posteromedial tenderness with valgus hyperextension and posteromedial impingement4; or posterolateral tenderness with lateral synovial plicae.6,7 • Ligamentous stability: Medial collateral ligament insufficiency can lead to posteromedial impingement followed by spur formation, then fragmentation and loose bodies or loss of extension; valgus testing is performed with the elbow in pronation at 60 to 75 degrees of elbow flexion.4,5,10 • O’Driscoll’s moving valgus test: Constant valgus torque is applied to a flexed elbow, and then the elbow is quickly extended. The result is positive if medial elbow pain is reproduced at the medial collateral ligament and is greatest between 120 degrees and 70 degrees.11 • Valgus extension overload test: Combined valgus and gentle terminal extension.4 • Neurovascular: Palpate the ulnar nerve during flexion and extension to determine if it subluxates, and assess a Tinel sign. Complete a distal examination for motor and sensory deficits. • Intra-articular injections of a local anesthetic may be helpful in assessing an intra-articular versus an extra-articular pathologic process. • Standard anteroposterior and lateral views are obtained (Fig. 43-1). • The hyperflexion and external rotation view can increase visualization of the posteromedial olecranon out of its fossa (Fig. 43-2). Figure 43-2 A, Hyperflexion and external rotation view of the same professional baseball player as in Figure 43-1 demonstrating posteromedial spur. B, Close-up view of the posteromedial fragment. • When radiocapitellar disease is suspected, the external rotation view is obtained with the anterior elbow surface oriented at 40 degrees oblique relative to the cassette. • Computed tomographic scanning and magnetic resonance imaging without contrast enhancement can provide additional information and details about synovial disease, particularly loose bodies, osteophytes filling the olecranon and coronoid fossa, capsular thickening, and chondral thinning, as well as useful information about the integrity of the collateral ligaments (Fig. 43-3). • Ultrasonography is an inexpensive modality that can provide additional information, especially in assessing collateral ligaments both statically and dynamically. • Dynamic ultrasonography is performed for functional assessment. The performance of dynamic ultrasonography requires education and skill of the radiologist in applying a valgus stress to the elbow. • The contralateral elbow can be evaluated to determine if gap formation is pathologic. • We prefer magnetic resonance imaging to assess the structural integrity of the UCL and to evaluate for intra-articular disease.

Elbow Synovitis, Loose Bodies, and Posteromedial Impingement

Preoperative Considerations

Typical History

Physical Examination

Imaging

Other Modalities

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Elbow Synovitis, Loose Bodies, and Posteromedial Impingement