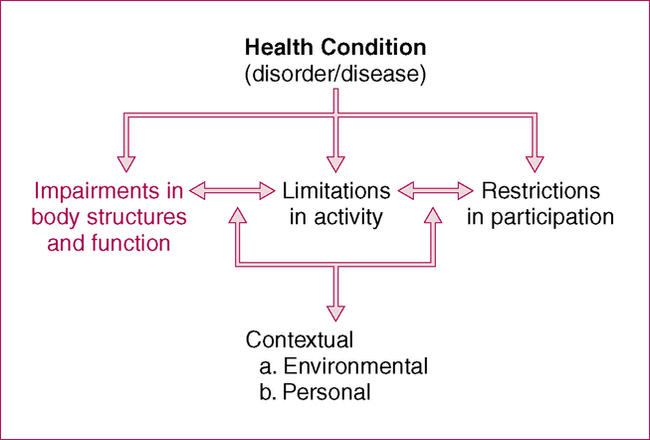

CHAPTER 8 After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, the reader will be able to: 1. Define impairments in body structure and function. 2. Appropriately classify impairments into categories for documentation purposes. 3. Document impairments concisely using appropriate terminology and abbreviations. According to the ICF model, body structures are defined as anatomic parts of the body such as organs, limbs, and their components. Body functions are physiologic functions of the body (including psychological functions) (Figure 8-1). Thus impairments are problems in body function or structure such as a significant deviation or loss. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice (the Guide; American Physical Therapy Association [APTA], 2001) provides a list of the tests and measures typically used by PTs. Of the 24 groupings in Chapter 2 of the Guide, 18 include some components of impairment-based tests and measures (Box 8-1). As emphasized in Chapter 7, the Guide does not organize tests and measures according to impairment and activity. This differentiation is often difficult and may be perceived as a continuum rather than a strict separation (see Figure 7-2). Quantifiable and objective data should be provided for impairment measures to be useful for diagnostic or evaluative purposes. Therapists should take care to document impairments with clarity and precision, avoiding vague and ambiguous terminology. Terms such as minimal, moderate, and maximal or good, fair, and poor are not particularly useful in descriptions of impairments and should be used sparingly in favor of more measurable, quantifiable assessments. Case Examples 8-1 to 8-3 give examples of documenting commonly assessed impairments in a concise but specific manner. Many impairment-based measures used in physical therapy are quantitative. Therapists should carefully choose impairment-based measures that have established reliability and validity. Examples of some commonly used standardized tests and measures are listed in Table 8-1. TABLE 8-1 Standardized Assessments of Impairments

Documenting Impairments in Body Structure and Function

Defining and Categorizing Impairments

Strategies for Documenting Impairments

CHOOSING WHICH IMPAIRMENTS TO DOCUMENT

SPECIFICITY OF DOCUMENTING IMPAIRMENTS

Standardized Tests and Measures

Measure

Population

Purpose

Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al., 1992)

Any neurologic condition, the elderly, individuals with balance problems

Measures balance ability on 14 balance items, such as standing with eyes closed, turning in place, and standing on one leg.

Cincinnati Knee Rating System (symptoms) (Barber-Westin et al., 1984)

Patients with knee dysfunction

Measures symptoms related to knee pain, including pain, swelling, and giving way, on a 6-point scale.

Constant Murley Score (Constant & Murley, 1987)

Patients with shoulder dysfunction

100-point scoring system: 35 points derived from patient’s reported pain and function; 65 points from assessment of ROM and strength.

Fugl-Meyer (Fugl-Meyer et al., 1975)

Stroke

Based to a large extent on Brunnstrom’s (1996) description of the stages of stroke recovery; most items scored on a 3-point scale (0, 1, 2); includes motor function, sensation, ROM, and pain

Glasgow Coma Scale (Jennett & Teasdale, 1977)

Brain injury

Rates alertness and cognitive awareness in three categories (eyes, verbal, and motor).

Mini-Mental State (Folstein et al., 1975)

Any individual with cognitive deficits or dementia

Assesses several categories related to cognition, including memory, recall, and language.

NIH Stroke Scale (Goldstein et al., 1989)

Stroke

11-item clinical evaluation tool used to assess neurologic outcome and degree of recovery. Includes evaluation of level of consciousness, motor function, and language, among others.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (Borg & Linderholm, 1970)

Cardiopulmonary

Patients rate their perceived exertion level on a 15-point scale.

Short physical performance battery (Guralnik et al., 1994)

General population; elderly patients

Evaluates balance, gait, strength, and endurance by examining a patient’s ability to stand with the feet together in the side-by-side, semitandem, and tandem positions, time to walk 8 feet, and time to rise from a chair and return to the seated position five times.

Tinetti Gait and Balance (Tinetti, 1986)

Any neurologic condition, the elderly, individuals with balance problems

Developed as a screening tool to identify older adults at risk for falls. Balance component measures balance on eight specific tasks; gait component measures specific gait parameters during ambulation. All are scored on a 0 to 2 scale. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree