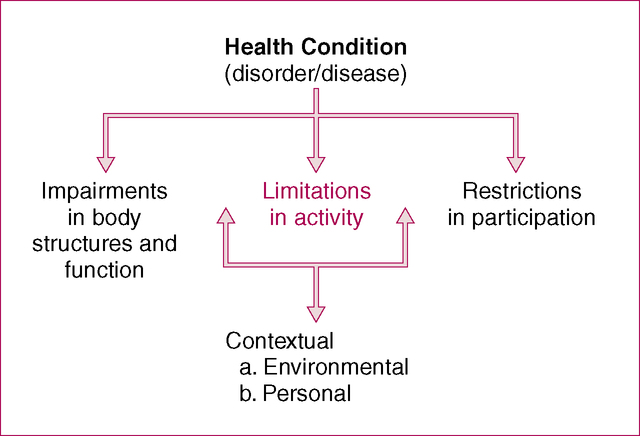

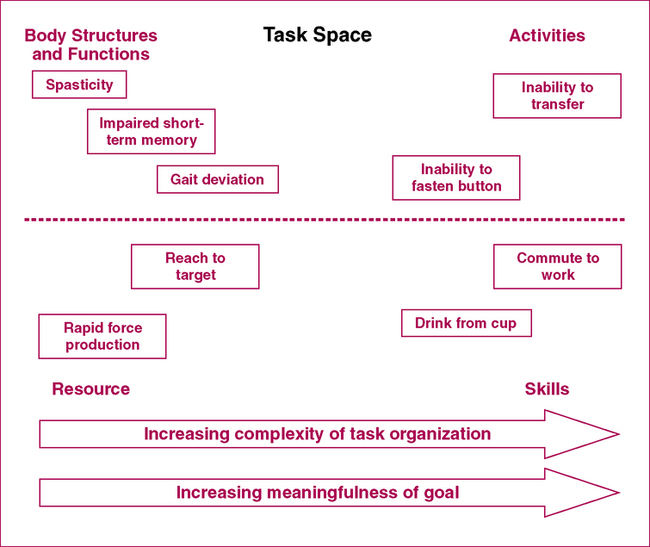

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, the reader will be able to: 1. Define activities and function. 2. Discuss the factors involved in deciding which activities should be included in documentation. 3. Identify and classify various aspects of documenting activities. 4. Appropriately categorize activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. This chapter discusses documentation and categorization of Activities (Figure 7-1). Activity as defined by ICF is the execution of a task or action by an individual. Many therapists typically refer to this as function, functional ability, functional status, or functional activities. As discussed in Chapter 1, the ICF has an inherently positive approach toward disablement. Thus therapists should be encouraged to document those activities a person is able to perform. In most cases, documentation should include abilities and limitations as they relate to function. However, the primary purpose of the ICF is to shed a positive light on disablement. In this book, we use the term Activities, in accordance with ICF terminology, as a global category for documenting skills, abilities, and limitations related to function. • Aerobic capacity and endurance • Gait, locomotion, and balance • Neuromotor development and sensory integration • Self-care and home management (including activities of daily living [ADLs] and instrumental activities of daily living [IADLs]) • Work (job/school/play), community, and leisure integration or reintegration (including IADLs) In several of these categories the differentiation between Body Structures and Functions and Activities is difficult, as in the case of “gait, locomotion, and balance.” The task of walking is certainly an activity, but describing the details of the gait pattern or the balance needed to maintain walking is more closely related to impairment of body functions. In fact, the differentiation between impairments and activities may be considered as a continuum rather than a strict separation. Figure 7-2 and Box 7-1 illustrate this concept. This continuum is discussed in more detail below. Tasks represent the interface between activities and body structures and functions (see Figure 7-2). Evaluation of the movement patterns and strategies used to perform such tasks provides important insight into the underlying impairments that affect activities. Task evaluation may bridge many functional skills. For example, the ability to squat is an important task for functional activities ranging from using the bathroom to picking up an object. Importantly, therapists may use task analysis to derive a deeper understanding of the contribution of various impairments to activity performance. Documentation of tasks therefore often includes information about how the movement was performed and the effect of any impairments on functional performance. Box 7-2 presents examples of common activities related to personal, occupational, and leisure roles. Personal Activities are further divided into ADLs and IADLs. ADLs are the basic tasks of everyday life—eating, dressing, bathing, and so on. IADLs are not necessarily critical for everyday functioning but are important for independent functioning within a community—answering the telephone, managing finances, and so on. This list can be used as a guide to documentation of activities. PTs can create subheadings within this section of the report to better organize the information and improve readability (Case Examples 7-1, 7-2, and 7-3). It is often useful to group activities or tasks together (e.g., ambulation or transfers) and include all related tasks under their appropriate headings.

Documenting Activities

Defining and Categorizing Activities

Documenting Task Performance

Documenting Performance of Functional Activities

Documenting Activities