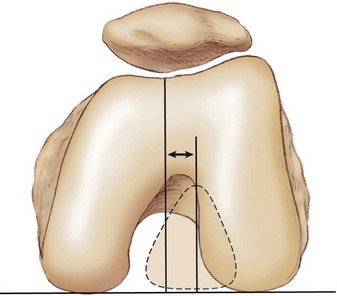

Chapter 91 Although the emphasis of this chapter is on tibial tuberosity surgery for patellofemoral disease, the multifactorial nature of patellofemoral dysfunction requires an acknowledgment that a patellofemoral problem is rarely addressed by a single surgical treatment. Tibial tuberosity repositioning must be examined with a full appreciation of proximal soft tissue balance, limb rotation, and articular cartilage disease (grade, site, and extent). Although positive outcomes were initially reported for many distal realignment patellofemoral surgeries, early positive results often deteriorated markedly over time. With the Hauser1 posterior medial tuberosity transfer, although stability was maintained, patellofemoral cartilage degeneration predictably occurred over time. Thus, in general, patellofemoral surgery not only must address the acute problem but do so without causing intermediate and long-term problems such as chondrosis and arthrosis. Application of a more scientific approach to patellofemoral dysfunction has led to the identification of the importance of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) in restraint to lateral patellar instability, and it has refined and focused the limited role of lateral release to isolated, documented patellar tilt rather than global patellofemoral pain or instability. Likewise, the role of tibial tuberosity surgery for patellofemoral dysfunction continues to evolve both as an isolated procedure and in conjunction with proximal patellofemoral surgery. Indications espoused for tuberosity surgery (often in combination with proximal soft tissue surgery) at one point included patellofemoral pain, instability, chondrosis, and arthrosis. Straight tibial tuberosity medialization (TTM) was initially associated with the names of specific surgeons, including Roux,2 Elmslie, and Trillat3; anteriorization with Maquet4; and anteromedialization (AMZ) with Fulkerson.5 These tuberosity surgeries have, at times, been used to treat static patellar subluxation, recurrent lateral patellar instability, patellar pain, and patellofemoral chondrosis. Tuberosity surgery for treatment of recurrent or chronic patellofemoral dislocation or subluxation was based on the assumption that the primary pathologic process was in an increased Q (quadriceps) angle; for pain and chondrosis, elevation was promoted as the preferred procedure to dramatically decrease patellofemoral stress. Whereas it is obvious that repositioning of the distal point of the Q angle (tibial tuberosity) surgically does modify the Q angle, today the MPFL is accepted as the main restraint to lateral patellar instability. In fact, the Q angle, which formed the rational basis for planning of a TTM, is being questioned as a benchmark in light of the poor intraobserver reproducibility of the measurement as reviewed by Post.6 In addition, Fithian has questioned the role of TTM for lateral patellar instability. At the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine in 2005, he presented a case series of recurrent lateral patellar instability treated by MPFL reconstruction with or without TTM. The results were the same in both groups. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that Carney et al1 has reported excellent long-term results in prevention of recurrent patellar instability with TTM, although critics note that his report is a clinical outcomes series without radiographs that might have demonstrated arthrosis (as predicted to occur with excessive medialization of the tuberosity in biomechanical studies by Kuroda et al7). Furthermore, because the extent of medialization with TTM has been variably defined, critics could imply that (1) some of the patients with instability successfully treated by TTM experienced spontaneous healing of the MPFL, (2) the MPFL lesion was marginally injured, or (3) the TTM “overmedialized” the tuberosity and constrained the patella into stability. From a basic science approach, the initial tuberosity surgery focused on the action of the various force vectors on patellar position and motion and on the effect of tuberosity position on those vectors. However, the equation is more complicated; Teitge and colleagues,8 Powers and colleagues,9 Heino and colleagues,10 and others have emphasized the importance of the “other half” of the joint in motion—the trochlea and associated tibiofemoral torsion. Furthermore, Dejour and colleagues11 have drawn attention to the importance of trochlear morphologic features (dysplasia) in patients with lateral patellar instability. In a comparative study, Paulos and colleagues12 reviewed the efficacy of derotational high tibial osteotomy in the setting of significant tibial torsion, reporting that patients receiving derotational procedures had improved outcomes and had more symmetrical gait patterns than patients who underwent proximal-distal realignment. This finding was echoed by Fouilleron and colleagues,13 who reported very high satisfaction rates after derotational osteotomy for patients with femorotibial malrotation. Continued investigation is needed to better define the role of derotational osteotomies. In an attempt to objectify tuberosity surgery, we must define normal and abnormal positions of the tuberosity. We must in addition consider the extent of femoral internal torsion and tibial external torsion as per Teitge8 and Heino and colleagues.10 This objective approach to limb coronal and axial alignment from hip to ankle also measures (at the knee) an objective alternative to the Q angle, that is, the tibial tuberosity–trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance (Fig. 91-1). The TT-TG distance, as popularized by Dejour,14 quantitates the concept of tibial tuberosity malalignment locally at the knee. Studies suggest that a TT-TG distance of more than 15 to 20 mm is abnormal; most asymptomatic patients have distances that are less than 15 mm. Likewise, anteriorization was first shown mathematically to reduce patellofemoral stress, but direct measurement with pressure-sensitive film, real-time pressure transducer arrays, and finite element analysis modeling such as by Cohen and Ateshian show that although stresses are typically reduced with anteriorization, there is a unique response for each knee, and a global 50% force reduction cannot be assumed. More recently, measures of trochlear contact pressures by Rue and colleagues15 confirmed the utility of straight anteriorization in reducing patellofemoral contact pressure. Thus load transfer should play an important role in surgical planning, as opposed to the assumption that there will be an absolute decrease in stress. With use of these and other objective parameters, further studies may objectively quantify the preoperative pathologic process to aid in planning of tuberosity surgery. Subgroups considered for tuberosity surgery include patients with static subluxation of the patella, those with patellofemoral chondrosis that requires load optimization, and those with recurrent lateral instability with or without static subluxation. The history will be highly variable for each subgroup, from insidious onset of patellofemoral pain to pain that began after a patellar instability episode. The standard patellofemoral history as outlined by Post6 should be elicited. Function aspects need to be documented, including the amount of energy needed to cause instability and the degree of stress necessary to cause pain. Prior surgical operative notes are useful, as are the intraoperative images. • Focal site or sites of maximal pain (especially at prior scars) or diffuse pain with any touch (to suggest chronic regional pain syndrome; see the discussion of contraindications) • Patellar displacement (measured in trochlea quadrants) • Patellar height (normal, infera, alta) • Tuberosity position relative to the center of the trochlea (Q angle less reliable) • Limb rotation (femoral and tibial internal and external rotation) • Muscle bulk and strength, with attention to the vastus medialis obliquus • Patellar tracking through active and passive range of motion • Individual variations of adequacy of the MPFL • Patellar tilt or extent of eversion, especially with prior lateral release • Patellar crepitation (document angle of flexion at which this occurs) • Apprehension: classic lateral versus global versus medial

Distal Realignment for Patellofemoral Disease

Preoperative Considerations

Typical History

Physical Examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Distal Realignment for Patellofemoral Disease