Distal Femur

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Distal femoral fractures account for about 7% of all femur fractures.

If hip fractures are excluded, one-third of femur fractures involve the distal portion.

A bimodal age distribution exists, with a high incidence in young males from high-energy trauma, such as motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents or falls from a height, and a second peak in elderly women from minor falls.

There is a 1:2 ratio of men to women.

Open fractures occur in 5% to 10% of all distal femur fractures.

ANATOMY

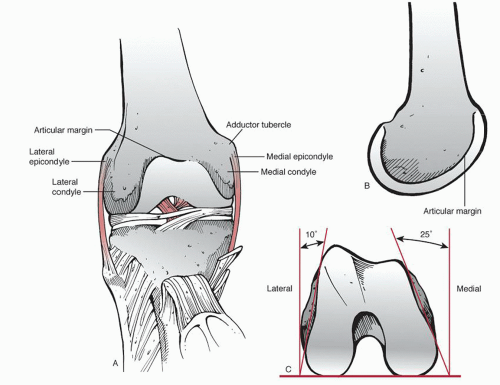

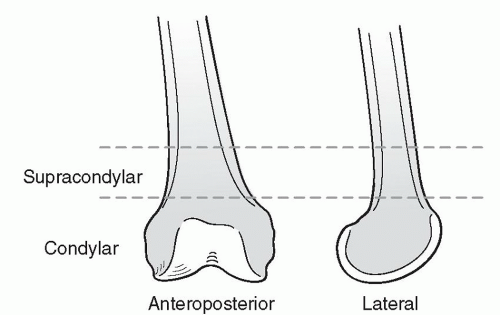

The distal femur includes both the supracondylar and condylar regions (Fig. 33.1).

The supracondylar area of the femur is the zone between the femoral condyles and the junction of the metaphysis with the femoral shaft. This area comprises the distal 10 to 15 cm of the femur.

The distal femur broadens from the cylindrical shaft to form two curved condyles separated by an intercondylar groove.

The medial condyle extends more distally and is more convex than the lateral femoral condyle. This accounts for the physiologic valgus of the femur.

When viewing the lateral femur, the femoral shaft is aligned with the anterior half of the lateral condyle (Fig. 33.2).

When viewing the distal surface of the femur end on, the condyles are wider posteriorly, thus forming a trapezoid.

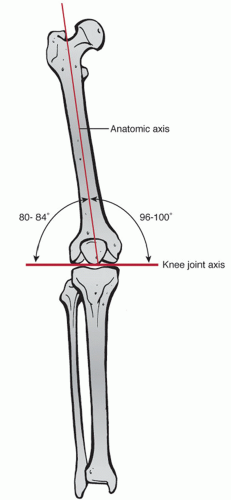

Normally, the knee joint is parallel to the ground. On average, the anatomic axis (the angle between the shaft of the femur and the knee joint) has a valgus angulation of 9 degrees (range, 7 to 11 degrees) (Fig. 33.3).

Deforming forces from muscular attachments cause characteristic displacement patterns (Fig. 33.4).

Gastrocnemius: This flexes the distal fragment, causing posterior displacement and angulation.

Quadriceps and hamstrings: They exert proximal traction, resulting in shortening of the lower extremity.

FIGURE 33.1 Schematic drawing of the distal femur. (Adapted from Wiss D. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.) |

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Most distal femur fractures are the result of a severe axial load with a varus, valgus, or rotational force.

In young adults, this force is typically the result of high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle collision or fall from a height.

In the elderly, the force may result from a minor slip or fall onto a flexed knee.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Patients typically are unable to ambulate with pain, swelling, and variable deformity in the lower thigh and knee.

Assessment of neurovascular status is mandatory. The proximity of the neurovascular structures to the fracture area is an important consideration. Unusual and tense swelling in the popliteal area and the usual signs of pallor and lack of pulse suggest rupture of a major vessel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree