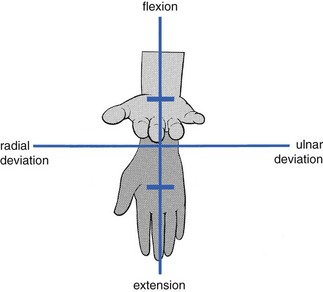

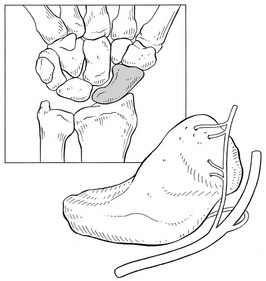

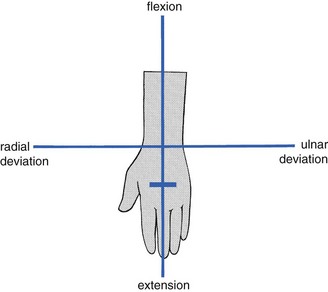

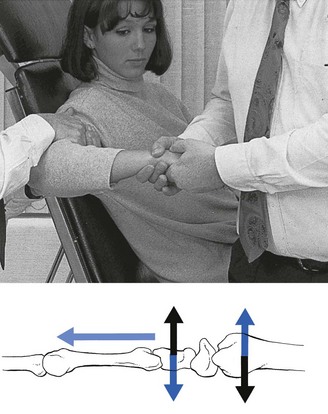

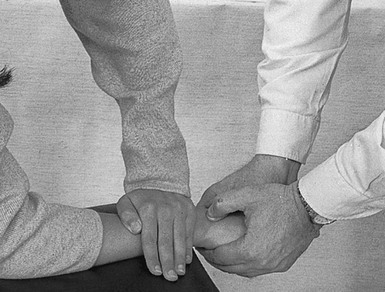

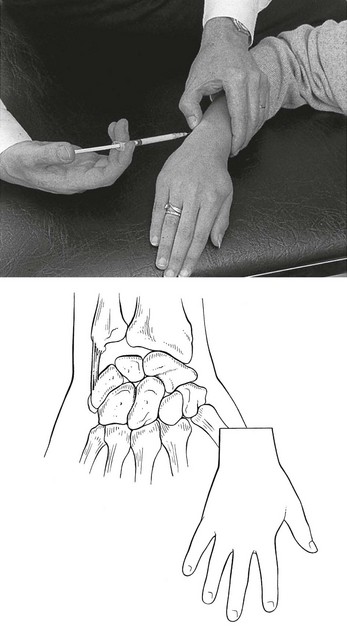

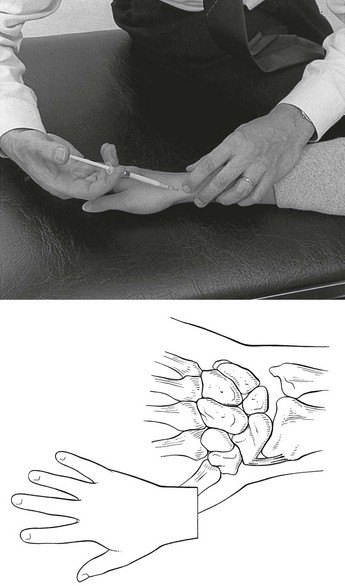

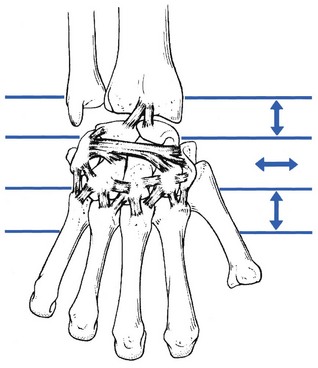

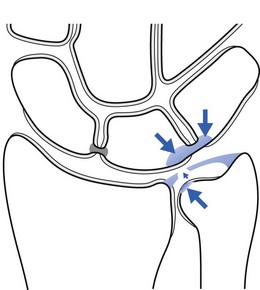

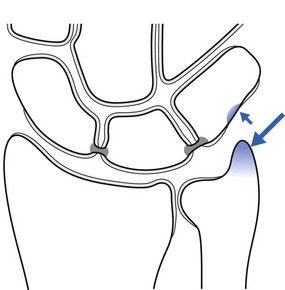

23 The capsular pattern is an equal degree of limitation of flexion and extension (Fig. 23.1). In advanced arthritis, fixation of the wrist in the neutral position takes place. The discovery of a capsular pattern following a trauma should always induce further examination. Uncomplicated traumatic arthritis is rare and the finding of a post-traumatic capsular pattern is highly suggestive of a fracture. The radiographic picture is unreliable because it may take up to several weeks for radiological evidence of a fracture to be conclusive.1 This delay may be responsible for serious complications because failure to diagnose and immobilize carpal fractures often leads to non-union and avascular necrosis.2,3 However, the clinical picture is so evident that the diagnosis should not be missed: any case of traumatic arthritis of the wrist lasting for longer than 2 days should be considered as a fracture. Inspection shows swelling of the wrist. On examination, a capsular pattern is found: passive flexion and extension are very painful and limited. The end-feel is that of a vibrant twang caused by a protective muscle spasm. Passive deviation of the wrist towards the painful side also increases the pain – a compression phenomenon that provides further evidence of a bony lesion. Careful palpation of the bones reveals localized tenderness. Most often the scaphoid bone is involved.4 In this case, tenderness will be elicited in the anatomical snuffbox.5 This is often described as a classic sign of scaphoid fracture and has a reported sensitivity of 90% but a low specificity of 40%.6 The scaphoid compression test also has a high sensitivity but a better specificity for scaphoid fractures. This test is performed by grasping the thumb and applying an axially directed compressive force along the line of the thumb metacarpal; wrist pain indicates a positive result.7 The scaphoid bone spans the joint between the proximal and distal rows of carpal bones and is most vulnerable: scaphoid fracture comprises between 51 and 78% of all carpal fractures.8–11 Young males and persons between 10 and 19 years of age are at highest risk for scaphoid fracture.12–14 Scaphoid fractures occur most easily during loading of a hyperextended wrist, possibly in combination with ulnar deviation. This movement tightens the palmar ligaments (the radiocapitate and radioscaphoid ligaments), so stabilizing the scaphoid against the radius. As the proximal pole is strongly stabilized, further loading and extension of the wrist causes bending forces on the distal pole, which may result in fracture.15,16 Fractures may occur at any level in the scaphoid but the more proximal the fracture, the greater the chance of avascular necrosis of the proximal fragment.17,18 The main reason for this is the special nature of the scaphoid’s blood supply.19 The blood supply to the scaphoid can be divided into extraosseous and intraosseous sources. The extraosseous blood supply is primarily derived from a branch of the radial artery, the artery to the distal ridge of the scaphoid.20 The branches of this vessel enter the scaphoid through a foramen at the dorsal ridge at the level of the wrist (Fig. 23.2). These vessels then run proximally and palmarly within the medullary chamber, forming the intraosseous supply to the proximal pole.21 Since vascularity of the proximal pole is limited and dependent on intraosseous flow, acute proximal pole fractures have a potentially prolonged healing period, averaging 3–6 months, and there is higher incidence of non-union. Because of the danger of avascular necrosis developing, it is important to recognize a scaphoid fracture as quickly as possible. Acute scaphoid fractures are often missed on initial plain radiographs. Therefore an initial negative radiograph does not alter the clinical diagnosis. When clinical suspicion of a scaphoid fracture is high and plain films are negative, the traditional recommendation is for these patients to be immobilized in a thumb spica splint or cast, with repeat radiographs after about 2 weeks.22 Alternative imaging modalities for diagnosis include bone scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A bone scan reportedly shows focally increased uptake within 72 hours and is very sensitive for detecting a fracture, but may not be extremely specific.23–25 MRI has been reported to have 95–100% sensitivity and almost 100% specificity for scaphoid fractures.26–28 Additional advantages of MRI include its potential to assess vascularity of the proximal scaphoid pole when a fracture is present.29 Treatment consists of immediate immobilization of the wrist, which is protective and can decrease the incidence of non-union and avascular necrosis.30 The best position remains unclear. Several dissection studies have come to different conclusions.31–34 Immobilization seems to be best performed with a thumb–spica cast, holding the thumb in the palmar abducted position and the wrist in the mid-position but with an element of deviation towards the site of the fracture, which, for the scaphoid, would be radial deviation. This helps to press the fractured surfaces together and stimulates the healing process.15 The time needed for a scaphoid fracture to heal is variable, from a minimum of 6 weeks to as long as 9 months,35 but 90% of fresh fractures heal with adequate treatment.30 Fractures of the other carpal bones can occur. Frequently, multiple radiographic views and/or follow-up studies with tomograms or bone scans may be necessary for a definitive diagnosis.36 Displaced fractures may require open reduction and internal fixation.37,38 The wrist can become affected by any type of rheumatic disorder, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, progressive systemic sclerosis, psoriatic arthritis, gout and pseudogout, ankylosing spondylitis and sarcoidosis, but rheumatoid arthritis is one of the commonest, frequently affecting both wrists39 and often following involvement of the fingers. In the acute stage a capsular pattern is found on examination, together with swelling, warmth and synovial thickening. At this stage MRI can be a useful technique for reaching a diagnosis.40 Recently joint ultrasound has also proved to be an important tool to evaluate synovitis of the wrist.41 In addition to pain, the more chronic cases present with gross limitation of movement. At this stage, there is no longer any warmth and even the swelling has diminished; diagnosis is easily made on conventional radiographs. On examination, signs of internal derangement are found (Fig. 23.3): one movement, most often extension, is limited with – certainly in acute cases – an end-feel of muscle spasm. Other movements are full-range, although often painful – the result of overstretching the irritated ligaments (see p. 34). The bony subluxation may be visible and palpable if the wrist is held in flexion. There is local tenderness in the ligaments. The radiograph is negative: the edge of the subluxated bone appears merged with the others and cannot be visualized separately on the radiograph, nor can its position be measured against the superimposed margins of the other bones (Cyriax:43 p. 184). Palmar subluxation, mostly of the lunate bone, is very exceptional. It gives rise to (slight) limitation of flexion and may compress a palmar branch of the median nerve, causing paraesthesia in the corresponding territory (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb). • A ganglion at the dorsum of the wrist usually feels softer on palpation. It does not respond to manipulative treatment but can be diagnosed and treated by puncture. • Kienböck’s disease, un-united fracture and isolated arthrosis have a different history and can easily be detected on radiography (see p. 337). The aim of the manipulation is to perform a gliding movement between the rows of carpal bones during traction. The technique is executed as follows. The manipulator leans sideways but makes sure that the pull is only carried out with the distal hand, so as to obtain traction on the wrist. After the slack has been taken up, both hands are moved vertically up and down in opposite directions (Fig. 23.4). The little finger of the contralateral hand is kept in the palm of the patient’s hand to control movement; the manœuvre should result in a pure gliding movement and flexion–extension should be avoided. When this technique does not lead to full recovery, the next manœuvre is tried. The patient, assistant and manipulator maintain the same positions as in the previous technique. The manipulator’s distal hand is now moved slightly downwards, so that it grasps the patient’s hand at the level of the bases of the metacarpal bones. Using the other hand, the patient’s wrist is approached from above and encircled with thumb and index finger. The metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger is placed on the subluxated bone. The manipulator’s forearm is held vertically (Fig. 23.5). The manipulator leans sideways, applying traction with the distal hand and, having taken up the slack, executes a short, sharp squeezing manœuvre. The patient stands next to the couch, with the forearm, stabilized by the other hand, placed on the couch, the distal part level with the edge. The manipulator stands in front of the patient and grasps the hand in such a way that one thumb, reinforced with the other, is placed dorsally on the subluxated bone, while one index finger, reinforced by the other, is placed on the palmar aspect of it. The little fingers are placed in the palm of the patient’s hand, in order to prevent flexion–extension movements during the manipulation (Fig. 23.6). The four following disorders, all visible on radiograph, give rise to limited extension only. Avascular necrosis of the lunate was first described by Peste in 1843.44 The condition was then forgotten until 1910, when Kienböck recorded lunatomalacia, which he assumed had a vascular traumatic aetiology.45 Despite recognition of this disease entity for the past 100 years, its cause is still debated. Some investigators relate it to a stress fracture that leads to devascularization of the major segment of the lunate. Other authors consider the avascular necrosis to be the result of interruption of the vascularization of the lunate bone following excessive shear forces caused by acute trauma or repeated microtrauma.46 This would happen more easily in those lunate bones that are supplied by a single volar or dorsal blood vessel.47 Others suggest that a vascular non-traumatic process, with a minor infarction pattern in the proximal subchondral area, may be nearer to the truth.48 Avascular necrosis usually affects the dominant hands of males between 20 and 40 years of age.49,50 The symptoms come on spontaneously or as the result of minor injury, and usually interfere very significantly with work-related activities. The initial symptoms are pain and stiffness, which may vary from moderate to severe and incapacitating. The patient may also mention reduced strength in the hand.51 The classification of Kienböck’s disease is based on its roentgenological appearance.52,49,53: • Stage 1 consists of small fracture lines – bone scintigraphy54 or MRI55 will be required for diagnosis. • Stage 2 is rarification along the fracture line, usually on the volar pole. • Stage 3 shows sclerosis of the bone dorsal to the fracture site. • Stage 4 shows sclerosis of the bone dorsal to the fracture site, and collapse and secondary fracture with loss of architectural integrity of the lunate. Treatment methods extend from immobilization to revascularization surgery on the affected bone. However, there is still no gold standard for the treatment of Kienböck’s disease.56 A recent systematic review showed that, to date, there are insufficient data to determine whether the outcomes of any intervention are superior to placebo or the natural history of the disease.57 Avascular necrosis in other carpal bones has been described but is rare.58,59 This bony prominence at the base of the second and third metacarpals adjacent to the capitate and trapezoid bones may represent degenerative osteophyte formation and/or the presence of an os styloideum, an accessory ossification centre that occurs during embryonic development. The symptoms of a carpal boss may result from an overlying ganglion or bursitis, an exterior tendon slipping over this bony prominence, or from osteoarthritic changes at this site. Diagnosis is by X-ray.60 Ligamentous injuries range from minor sprains with no instability (which are discussed here) to complete rupture with gross instability (see p. 341).61 A 1 mL syringe, filled with 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide, and a 2 cm needle are used. The patient’s arm rests in pronation on the couch. The hand is brought into slight radial deviation. The tender spot is identified, and the infiltration given with bony contact and ligamentous resistance (Fig. 23.7). This rare disorder results in pain felt at the radial aspect of the wrist during passive ulnar deviation. A more common cause of these symptoms is a tendinous lesion in the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons (see p. 354). Differential diagnosis is easy because, in tendinitis, resisted movements are also positive. The patient sits with the forearm in the neutral position and the hand on the couch. The wrist is brought into slight ulnar deviation. The tender spot is palpated and 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide is infiltrated using a 2 cm needle (Fig. 23.8). During infiltration, ligamentous resistance and bony contact should be felt. Care must be taken to avoid puncture of the radial artery. The patient sits with the hand over the edge of the couch. The therapist sits facing the patient’s wrist, which is flexed with one hand within the limits of pain. Friction is imparted with the other hand. The direction depends on the course of the ligamentous fibres: the radiocarpal and carpometacarpal ligaments are aligned in the same longitudinal axis as the forearm, while the intercarpal ligaments have a more or less transverse direction (Fig. 23.9). For a radiocarpal or carpometacarpal ligament, the direction of the friction is transverse on the ulnar–radial axis. Friction is given with either the index finger, reinforced with the middle finger (Fig. 23.10), or with the thumb. As the lesion is very localized, the therapist must make sure that the finger remains deep between the extensor tendons and does not pass over them. An intercarpal ligament is given friction with the thumb and in a proximo–distal direction (see Fig. 23.9). Ulnar impaction syndrome, also known as ulnar abutment or ulnocarpal loading, is a degenerative condition characterized by ulnar wrist pain related to excessive load bearing across the ulnar aspect of the wrist. Chronic impaction between the ulnar head and ulnar carpus results in periostitis and degeneration of the lunate bone, triquetral bone and distal ulnar head, and degenerative tears of the triangular fibrocartilage complex (Fig. 23.11).62 Radiographic changes include subchondral sclerosis and cystic changes in the ulnar head, ulnar aspect of the proximal lunate bone, and proximal radial aspect of the triquetral bone. MRI is helpful in detecting occult disease in the early stage.63 Treatment will depend on the severity of the lesions. Periostitis responds well to local infiltration with 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide, provided that further irritation is avoided. This can be done by avoiding the extremes of wrist movement in the loaded position or by the application of a splint or a cast. In more advanced cases or in lesions of the triangular fibrocartilage complex, arthroscopy and surgery will be needed.64,65 This ulnar-sided wrist pain is caused by impaction between an excessively long ulnar styloid process and the triquetral bone.66 The ulnar styloid process is a continuation of the prominent subcutaneous ridge of the shaft of the ulna, which projects distally towards the triquetral bone for a variable distance (2–6 mm).67 A single or repetitive impaction between the tip of the ulnar styloid process and the triquetral bone results in contusion, which leads to periostitis of the opposing surfaces. If a single-event trauma is forceful enough, fracture of the dorsal triquetral bone may occur.68 The diagnosis of this condition is made on the basis of pinching pain during ulnar deviation and radiographic evidence of an excessively long ulnar styloid process. MRI may show chondromalacia of the ulnar styloid process and proximal triquetral bone (Fig. 23.12).69 Pain at the dorsal aspect of the wrist may occur as the result of repetitive extension movements during weight bearing, as frequently happens in gymnastics or other high-energy sports; this may lead to periostitis at the distal epiphysis of the radius or the proximal carpal bones,70,71 described as ‘wrist impingement’ syndrome72 or ‘stress reaction’.73 The pain is elicited each time the patient puts weight on an extended wrist. Periostitis responds well to local infiltration with 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide, provided that further irritation is avoided. This can be done by avoiding the extremes of wrist movement in the loaded position or by the application of a splint or a cast, if necessary. Surgery can be performed in recurrent cases or to avoid long-term complications.74 Repetitive compressive loading may result in stress fractures of the distal part of the radius, the scaphoid and the capitate bones. Scintigraphy and MRI are diagnostic and immobilization in a cast is therapeutic.75,76

Disorders of the wrist

Disorders of the inert structures

Limited range: capsular pattern

Traumatic arthritis

History and examination

Treatment

Rheumatoid arthritis

Limited range: non-capsular pattern

Carpal subluxation

History and examination

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Basic technique: manipulation for carpal subluxation

![]()

Second technique: manipulation for carpal subluxation

![]()

Alternative technique: manipulation for carpal subluxation

Other joint problems

Aseptic necrosis of the lunate bone (Kienböck’s disease)

Carpal boss

Full range

Ligamentous lesions

Sprain of the ulnar collateral ligament

Technique: infiltration

![]()

Sprain of the radial collateral ligament

Technique: infiltration

Sprain of the dorsal ligaments

Technique: deep transverse friction

![]()

Wrist impaction syndromes

Ulnar impaction syndrome

Ulnar styloid impaction syndrome

Radial impaction syndrome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the wrist