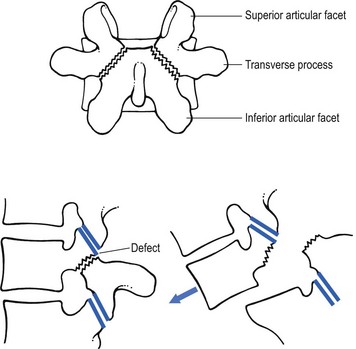

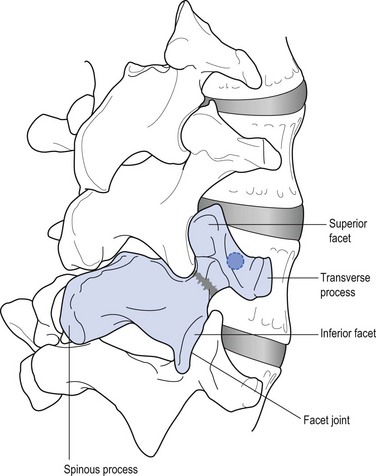

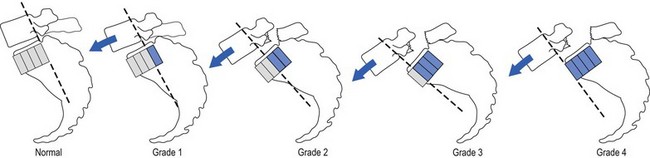

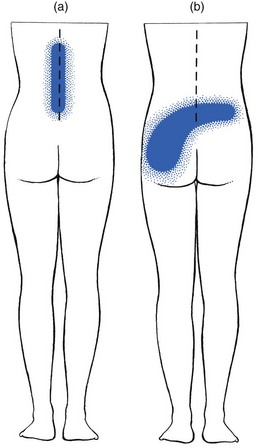

In 1782, the Belgian gynaecologist Herbiniaux described a severe case of lumbosacral luxation, which he considered as a potential obstetrical problem.1 A precise definition of spondylolisthesis was first given by Kilian in 18542 – a spinal condition in which all or a part of a vertebra (spondylo) has slipped (olisthy) on another. Wiltse et al9 described five major types: • Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is secondary to a congenital defect of the first sacral–fifth lumbar facet joints, with gradual slipping of the fifth lumbar vertebra. • Isthmic or spondylolisthetic spondylolisthesis is the most common type of spondylolisthesis. The basic lesion is in the pars interarticularis. The vertebra above can slip as the result of a lytic process, an elongation without lysis or an acute fracture (subtypes a, b and c). If a defect in the pars interarticularis can be identified, but no slip has occurred, the condition is called a ‘spondylolysis’. • In degenerative spondylolisthesis an advanced degeneration of the facet joints and a progressive change in the direction of the articular processes allow the vertebra to slip forwards. The condition occurs four times as frequently in females than in males and nearly always at the fourth lumbar level (Cyriax:3 p. 288; Rosenberg4). The slip is never severe. This condition has been discussed in Chapter 35 on the stenotic concept. • Traumatic spondylolisthesis results from a fracture of a posterior element other than the pars interarticularis. • Pathological spondylolisthesis develops as the result of weakness caused by a local or generalized bone disease. In this chapter we discuss only the spondylolytic spondylolistheses. Isthmic spondylolisthesis has been defined as ‘a condition in which fibrous defects are present in the pars interarticularis, which permit forward displacement of the upper vertebrae and separation of the anterior aspects of the vertebra from its neural arch’ (Fig. 1).5 The aetiology of this bony defect (spondylolysis) has been discussed for decades but it is now widely accepted to be the result of a congenital weakness. The defect itself is not present at birth, however, but develops in childhood, probably as the result of repeated stress and trauma.6–8 Stress fractures form in the weakened pars interarticularis; fibrous tissue fills the gap, and further tension enlarges the defect.9 Forward slipping of the vertebral body therefore occurs most frequently between the ages of 10 and 15 years, and progression is unlikely after adolescence.10,11 The reported incidence of spondylolisthesis is between 4 and 7%,12–14 although a higher incidence has been reported among Eskimos (18–56%).15,16 Spondylolysis is visualized by an oblique view of the lumbar spine which shows the well-known ‘collar on the Scottie dog’s neck’ (Fig. 2). Forward slipping is best visualized on a lateral radiograph and the amount of listhesis is graded by the Meyerding’s system (Fig. 3):17 the upper sacrum is divided into four parallel quarters and the degree of slipping is calculated from the distance that the posterior edge of the fifth lumbar vertebra has shifted on the posterior edge of the sacrum in relation to the total width of the upper sacrum. Grade I is a shift of less than 25%, grade II between 25 and 50%, grade III between 50 and 75% and grade IV more than 75%. Some authors emphasize that there is a significant difference in measurements when the radiographs are taken with the patient in a recumbent rather than erect position.18 It should be emphasized that most cases of spondylolisthesis are asymptomatic. Even severe displacements may be present in very active patients, without the slightest discomfort. In a radiological study of 996 adult patients with low back pain, MacNab found spondylolisthesis in only 7.6%, which is not significantly higher than in the population as a whole (4–6%).19 Therefore caution must be taken before ascribing back pain or sciatica to spondylolisthesis and the radiological demonstration of a defect in a patient with back pain does not always indicate that the source of the symptoms has been discovered.20,21 As early as 1945, Key stated that symptoms in spondylolisthesis were far more often caused by a disc lesion than by slippage of the vertebra.22 The clinical features are exactly the same as in patients without spondylolisthesis, and nothing in the history or clinical examination arouses suspicion, except some irregularity of the spinous processes on examination. Radiographs carried out in the erect posture disclose the slip. It is obvious that the management of disc lesions occurring in spondylolisthetic spines is exactly the same as in those without bony defects. The only difference is probably the liability to recurrence of acute or chronic discodural conflicts. As in other forms of lumbar instability, sclerosing injections can have a good preventive outcome after reduction has taken place. Spondylolisthesis can cause both backache and sciatica. The former has postural ligamentous characteristics: the ache is central, sometimes with vague and bilateral radiation over the lower back. The discomfort is associated more with maintaining a particular position than with exertion. Dural symptoms are absent. There are no articular signs or symptoms; lumbar mobility is full and painless. Root signs are also absent. The only clinical finding is a bony irregularity palpated over the spinous processes. Treatment is that for ligamentous backache and consists of sclerosing injections (see p. 579). Spondylolitic sciatica very much resembles a bilateral lateral recess stenosis but the patient is much younger. Increasing pain and paraesthesia appear in the standing position and may force the patient to sit or lie down, which causes the symptoms to disappear. Dural symptoms are absent. Clinical examination reveals little: there is a normal range of movement without pain. Root signs, such as positive straight leg raising, weakness or sensory loss are not found (J. Cyriax, personal communication, 1983; Calliauw and Van23). The cause of sciatic pain in spondylolisthesis is unknown. The different hypotheses are: • The forward movement of the listhetic vertebra drags on the nerve roots, which engage painfully against the shelf formed by the stable vertebra below (Cyriax:3 pp. 287–290). • A fibrocartilaginous mass, with or without small ossicles, may form at the defect in the pars interarticularis. Adhesions around the nerve root and compression result.24 • With the forwards and downwards drop of the vertebral body, the pedicles descend on the nerve roots and kink them as they emerge through the foramen.19 • A forwards slipping of the vertebral body moves the transverse processes in a forwards and downwards direction, allowing the L5 roots to be pinched between the sacrum and transverse process (the ‘far-out’ 25). If leg pain is a significant problem, nerve root infiltrations can often abolish it. The patient can also be advised to wear a corset during occasional strenuous activity. If root pain cannot be abolished by these conservative measures, surgery should be considered. Surgical intervention can also be considered if the listhesis is progressive or the patient presents with a Meyerding grade III or IV. The gold standard of surgical treatment is fusion in situ.26 The different techniques for fusion have mixed and variable results27–29, and the possibility of complications.30 Recently, reduction of the listhesis and stabilization, whether by bilateral lateral fusion or interbody fusion, has been recommended.31,32 It should be remembered, however, that even in grade III and IV listhesis, good results have been described after non-surgical treatment.33 Apel et al.34 reported on the long-term results (40 years) after surgical and non-surgical treatment of grade I and grade II spondylolisthesis. Of the conservatively managed patients, all functioned well. Among those undergoing surgery, poor results were confined to those patients in whom the fusion failed, and a pseudarthrosis developed (40%). Frennered et al35 stated that operative treatment for low-grade spondylolisthesis does not seem to give better results than conservative treatment. More recent prospective studies, however, conclude that surgical management of adult isthmic spondylolisthesis improves function and relieves pain more efficiently than an exercise programme.36,37 Osteoporosis is a metabolic disease, related to several different disorders. It is characterized by a reduction of bone mass which occurs predominantly in the axial skeleton, the femoral neck and the pelvis. By radiographic criteria, 18% of men and 29% of women between the ages of 45 and 79 years of age have evidence of osteoporosis and more sensitive methods for determining vertebral bone mineral density show that 50% of women past the age of 65 have asymptomatic osteoporosis.38 The radiographic appearances are changes in bone porosity, trabecular pattern and vertebral body shape (the so-called biconcave fishmouth vertebrae).39 It is a common mistake to believe that these changes account for patients’ backache. It should be remembered that uncomplicated osteoporosis does not cause any symptom except some loss of height of the spine. Thus the major explanation for long-standing back pain in the elderly does not appear to be related to spinal osteoporosis and, if a radiograph shows uncomplicated osteoporosis in a symptomatic patient, other sources for the pain should be sought.40 Osteoporosis may, however, lead to a pathological fracture. If this takes place, a sudden pain in a girdle distribution will result. Osteitis deformans or Paget’s disease of bone41 is a localized disorder characterized by a remarkable hyperactivity of osteoclasts and subsequent increase of osteoblastic bone deposition. As a result, the normal bone architecture is completely disturbed.42 In a vertebral body this can result in softening, broadening and collapse of the bone. The disease is reported to occur in approximately 4% of individuals over the age of 40.43 In the majority, the disease is restricted to a few bones. It must be emphasized that most patients with Paget’s disease are asymptomatic.44 The main problem for the clinician therefore is not the discovery of the Paget’s disease but the association of the back symptoms with the Pagetoid lesion. Back pain and the associated angular kyphosis arise as the result of collapse of the vertebral body. Sometimes new bone growth in the vertebral arch may compress nerve roots, resulting in a spinal stenosis or a lateral recess stenosis.45,46 This causes a wedge deformity. It usually occurs at the upper lumbar or at the thoracolumbar level and usually results from axial trauma or from flexion injuries (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic spine: non-disc lesions – disorders and their treatment). Wedging of a vertebral body may also result from a pathological fracture which is the consequence of senile osteoporosis, tumour, Paget’s disease or tuberculous caries. • the pain is usually located in the upper lumbar area: pathological fractures occur more often in the ‘forbidden area’ • dural signs are absent: although the patient describes an intense backache, coughing does not hurt • inspection reveals an angular kyphosis • examination shows a capsular pattern, with symmetric limitation of lateral flexion • there are no dural signs: straight leg raising is normal, which is always suspicious in a case of acute lumbago. Isthmic spondylolysis is considered to represent a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis of the neural arch. There is a relatively high incidence of radiographically identified spondylolysis in the general population, but the vast majority of these lesions probably occur without associated symptoms.6,47,48 The incidence of spondylolysis in the young athletic population shows an almost fivefold increase compared to the general population,49 with the highest rates in weight lifters,50 gymnasts51 and football players.52 Given this high incidence of asymptomatic lesions, the relation between unilateral or bilateral back pain and a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis remains unclear.53 However, recent histological studies could identify a well-developed ligamentous structure covering the defect (‘the spondylolysis ligament’) and containing thin unmyelinated nerves.54,55 Infiltration of bupivacaine hydrochloride (Marcain) into the pars defect produced temporary symptom relief, which proves the existence of symptomatic lesions.56 Symptomatic lesions appear to be particularly a clinical problem in adolescents, especially adolescent athletes. Although clinical features of active spondylolysis do not differentiate this condition from other causes of low back pain,57 suspicion may arise when an adolescent athlete presents with unlilateral backache without dural signs nor symptoms, and pain is provoked by full extension.58,59 On plain radiography, the defect in isthmic spondylolysis is visualized as lucency in the region of the pars interarticularis. The lesion is commonly described as having the appearance of a collar on the ‘Scotty dog’ seen in lateral oblique radiographs (see Fig. 2). Plain radiography has limited sensitivity, however, and nowadays bone scintigraphy with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is considered as the gold standard of investigation.60,61 Conservative treatment consists of relative rest and the avoidance of activities associated with increased pain.62 Stress fractures of the contralateral pedicle in patients with unilateral spondylolysis has recently been reported63,64 and termed ‘pediculolysis’.65 The development of a unilateral spondylolysis probably leads to a redistribution of forces, resulting in a stress fracture of the contralateral pedicle. Alternatively, not a fracture but a compensatory sclerosis and hypertrophy of the contralateral pedicle develop.66,67 To date, it is not clear if the lesions are responsible for particular clinical syndromes.68 Classically, neoplastic lesions in the lumbar spine are classified as benign or malignant lesions. The latter are subdivided into primary malignancies and metastases. Benign and primary malignant neoplasms are rare in the lumbar spine, whereas secondary deposits are common. Although the diagnosis of tumours of the lumbar spine is largely dependent on radiological examinations, it must be remembered that 30% of the osseous mass of bone must be destroyed before a lesion is radiologically evident.69 Therefore radiographs do not reveal early disease and too much reliance on radiographic appearances can give both the patient and the physician a false feeling of security. Therefore, in the diagnosis of neoplastic lesions, the history and clinical examination remain vital. Special attention must be paid to warning signs. When routine radiographs fail to support the clinical impression, a radioisotope scan must be obtained, in order to demonstrate the presence of a malignant lesion and the extent of the spinal involvement. This constitutes about 12% of all benign tumours (Dahlin and Unni:70 pp. 88–101) and appears mostly in children and adults below the age of 30 years. The pain is frequently exacerbated at night and is often relieved by small doses of aspirin.71 Treatment consists of local excision of the tumour. This is a rare benign neoplasma of bone but has a predilection for the spine: approximately 40% of all osteoblastomas are found in the posterior elements of the spine and sacrum.72 The tumour is seen most frequently in males under the age of 30 years.73 The back pain is localized, insidious in onset, with a duration of months or years and not as severe as in osteoid osteoma. Clinical examination may reveal muscle spasm and localized tenderness. Because of the expansive nature of the tumour, slowly progressive compression of nerve root(s), with radicular pain and evidence of neurological deficit, may occur. These account for less than 1% of symptomatic primary bone tumours (Mirra:74 pp. 492–497), although postmortem studies have demonstrated that asymptomatic lesions exist in 12% of all vertebral columns. This implies that most of these lesions remain asymptomatic throughout life. The thoracic spine is the location for 65%, the cervical spine 25% and the lumbar for only 10%. Patients with symptomatic haemangiomas are usually between 40 and 50 years of age.75 The main complaint is localized pain. Clinical examination may show limitation of movement from muscle spasm and localized tenderness. Increased weakening may result in a pathological fracture, which in turn may cause neurological symptoms.76 Since vertebral haemangiomas are usually asymptomatic and have a benign course, treatment is expectant. Radiation seems to afford a good outcome in patients with constant, disabling pain.77 This is a rare bone lesion characterized by the infiltration of bone with histiocytes, mononuclear phagocytic cells and eosinophils. It was first described by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1944.78 It occurs most commonly in children and adolescents79 and only 10% of the lesions are localized in the spine. Local and constant back pain is the first symptom. Clinical examination shows muscle spasm and local tenderness. If the lesion affects a vertebral body, a flattening – vertebra plana – will result. This spontaneous collapse of the vertebral body in children was first described by Calvé in 192580 and was thought to be a manifestation of osteochondritis juvenilis.79 It seems that the collapse of the vertebra induces spontaneous healing of the granuloma, in that symptoms usually cease after the body has collapsed.81,82 This is a benign, cystic vascular lesion of bone. The majority of aneurysmal bone cysts occur in the long bones of the extremities of young adults.83 The lumbar spine is affected in only 10% of cases.84 The clinical presentation is lumbar pain that usually has an acute onset and increases in severity over a short period of time. Depending on the location and size of the lesion, the other clinical manifestations vary. If the lesion is at the spinous or transverse processes, the pain remains local.85 If the vertebral body is affected, the lesion may expand, which can result in weakening of the bone, pathological fractures and serious neurological deficits. Although aneurysmal bone cysts are benign lesions, they may cause severe damage because of their expansive characteristics. The lesion therefore must be diagnosed early and treatment instituted without delay in order to keep disability to a minimum. Treatment is by surgery, radiotherapy or cryotherapy. Malignant tumours of the spine predominantly affect patients over the age of 50 and are mostly localized in the anterior spine elements. Metastatic lesions of the axial skeleton are much more common than primary malignant lesions (chordoma, myeloma and chondrosarcoma), the overall ratio being 25 : 1 (Francis and Hutter;86 Mirra:74 pp. 448–454). This is a slowly developing malignant tumour that originates from the remnants of notochordal tissue and therefore occurs exclusively in the midline of the axial skeleton. It has a predilection for either end of the spinal column: 50% of cases occur in the sacrum and 38% in the skull base.87 The lesion is rarely reported below the age of 30 years and most tumours become evident between the ages of 40 and 70.88 Chordomas are slow-growing tumours with a locally invasive and destructive character. The common sacral tumours may be difficult to detect. The patient initially presents with localized pain in the sacral area or with coccygodynia. The pain is dull, constant and not relieved by recumbency. Often it is of long duration and only moderate, so that it does not force the patient to seek treatment.89 Chordomas of the sacrum extend anteriorly into the pelvis. Because the dural sleeve is not involved, presacral invasion of the nerve roots does not provoke radicular pain. Straight leg raising is also not limited. However, gross muscular weakness of one or both legs, together with considerable sensory deficit is detected. Sometimes the patient presents with urinary or bowel incontinence as well.90 Such a gross paresis in the absence of root pain always suggests a tumour. A radiograph of the lumbar spine and sacrum discloses lytic bone destructions with calcified foci and a pre-sacral soft tissue mass.91,92 Patients with chordomas of the lumbar spine may present with localized central lumbar pain sometimes radiating bilaterally. Involvement of nerve roots may induce bilateral sciatica. Clinical examination then shows muscle spasm and bilateral weakness.93 Treatment consists of total resection of the tumour, which usually presents a major problem. Often partial resection, followed by radiation therapy, is the only option.94 Chemotherapy is ineffective.95 This is a malignant tumour that forms in cartilaginous tissue. The tumour is frequently located in the pelvis and lumbar spine and grows extremely slowly. The usual age of onset is between 40 and 60 years (Dahlin and Unni:70 pp. 227–259). The tumour may be symptomless over many years. Local pain is very suggestive of actively growing tumour. When neural elements are compressed by the tumour, abnormalities are found on neurological examination. The treatment of choice is total resection of the tumour. This is a malignant tumour of plasma cells and is the most common primary tumour of bone; the spine is almost always involved. The disseminated form is multiple myeloma and accounts for 45% of all malignant bone tumours (Dahlin and Unni:70 pp. 193–207). The patients are usually in an older age group, in that the disease is rare below the age of 50 years. Plasmacytoma is the solitary form and affects the spine in about 50% of patients.96 The most common complaint is of back pain, which does not vary with exertion, although initially may be relieved somewhat by bed rest. Malignant disease is suggested by steady worsening of the backache which eventually becomes continuous, irrespective of posture or movement. As the backache becomes more severe, sciatica, which is often bilateral, appears.97 The fact that the backache does not cease after the root pain comes on and that the root pain is bilateral, immediately draws attention to the possibility of an expanding lesion. Alternatively, the backache is sudden as the result of a pathological fracture. Radiographically, multiple myeloma is characterized by the presence of round lytic defects in the bone without any surrounding reactive sclerosis. Occasionally, lytic defects may not be obvious, and the radiograph shows nothing more than a diffuse osteopenia.98 In such circumstances the differential diagnosis must be made by laboratory examinations,99 which consistently reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate – seldom less than 100 mm/h. Characteristically, abnormal Bence-Jones proteins can be demonstrated in the urine.100 The most important test is serum protein electrophoresis, which identifies a monoclonal spike in more than 75% of patients and hypogammaglobulinaemia in 9%.101 The usual course of multiple myeloma is one of gradual progression. Systemic therapy with melphalan and cortisone may improve clinical symptoms, but the average survival seldom exceeds 5 years.102 The most common malignant tumour in the spine is metastatic cancer. The prevalence of metastases increases with increasing age, and patients who are aged 50 years or older are the population at greatest risk. Neoplasms frequently associated with spinal metastases are of prostate,103 breast, lung, thyroid and colon.104 Up to 70% of patients with a primary neoplasm will sooner or later develop metastases in the thoracolumbar spine.105 The predilection of metastases for the lumbar spine may be explained by the functioning of Batson’s plexus. This is a venous network, located in the epidural space between the bony spinal column and the dura mater. Because this plexus has no valves to control blood flow, metastatic cells may easily enter it and lodge in the connected sinusoidal systems of the red bone marrow of the vertebral bodies.106 Some suspicion may arise when, for the first time, a patient over the age of 50 presents with an attack of low back pain. Especially if the pain has a gradual onset and increases in intensity over time, the patient should be suspected of suffering from a malignant disease. The concern should be even greater if there is a prior history of malignancy. In the beginning the pain is localized but very soon it spreads down the leg in a distribution not corresponding to a single root. Sometimes there is bilateral sciatica and the lumbar pain does not ease but becomes even worse when the sciatica appears. Because the tumour often extends into the epidural space, dural symptoms may be present. However, not all skeletal metastases cause pain: symptoms may occur only when the lesion is complicated by a pathological fracture.107 • Weakness of the psoas muscle • Signs of involvement of two or three consecutive roots, or non-adjacent roots • Discrepancy between pain and weakness It is important to stress that radiographs may be normal and are not reliable early in the course of a metastatic lesion. Clinical symptoms and even signs of gross muscular weakness may appear before the radiograph shows erosion or collapse of bone.108 If the clinical features of metastasis are present but the radiographic examination remains negative a bone scan may be necessary to establish the diagnosis.109 MRI examination is a quite sensitive complementary technique and appears to be more specific for metastasis in certain locations of the spine.110 This disease usually affects the sacroiliac joints initially, and then appears in the thoracolumbar area. Thereafter, the lower lumbar, the thoracic and the cervical spine also become affected111 (see Ch. 43). Although the lesion invariably starts at the sacroiliac joints, it is possible that this does not cause any symptoms and the first complaint is then of backache. Backache in ankylosing spondylitis is typically intermittent; it comes and goes irrespective of exertion or rest. However, the pain and the stiffness are greatest in the morning and usually improve with movement. Several segments at the upper lumbar and thoracolumbar level become involved at about the same time.112 Because the pain is usually limited to the central part of the spine and does not refer laterally, the patient complains of vertical distribution (Fig. 4a). This contrasts with the more or less horizontal, gluteal and asymmetrical reference of dural pain in a lumbar disc disorder (Fig. 4b). Diagnosis is confirmed by radiography of the sacroiliac joints. Because lumbar manifestations occur some years after sacroiliac manifestations, plain radiographs of the latter will almost certainly reveal the typical narrowed joint spaces and surrounding sclerosis. In later stages, radiographic abnormalities also appear in the lumbar and thoracolumbar spines. First there are signs of osteitis of the anterior corners of the vertebral bodies. This results in the typical ‘squaring’ of the vertebrae. Healing of the inflammation leads to a reactive sclerosis in the anterior portions of the vertebral bodies. Later on, thin, vertically orientated calcifications of the annulus fibrosus and anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments appear. These growing ‘syndesmophytes’ can enclose the whole axial skeleton, which is then called a ‘bamboo spine’.113 Rhematoid arthritis, a systemic chronic inflammatory disease which involves synovial joints, may affect the facet joints of the lumbar spine, although it is found more frequently in the cervical articulations. The disease does not affect the sacroiliac joints.114 Those who develop low back pain secondary to rheumatoid arthritis usually have a long-standing history of disease in the joints usually affected by the illness.115 Pain stems from the facet joints and therefore its reference does not spread beyond the hips.116 The symptoms are inflammatory in nature, with pain and stiffness increasing with rest, greater in severity in the morning and improving during activity. Clinical examination reveals limitation of movement in a capsular way and localized tenderness. The diagnosis is based upon the typical history, the clinical appearances of the peripheral joints and the characteristic laboratory findings.

Non-mechanical disorders of the lumbar spine

Pathology

Disorders

Spondylolisthesis

Aetiology

Grading

Clinical findings

Spondylolisthesis with secondary disc lesion

Spondylolisthesis of itself causing symptoms

Treatment

Osseous disorders

Osteoporosis

Paget’s disease

Fractures

Crush fracture of the vertebral body

Spondylolysis

Stress fractures of the lumbar pedicle

Tumours

Benign tumours

Osteoid osteoma

Osteoblastoma

Haemangiomas

Eosinophylic granuloma

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Malignant tumours

Chordoma

Chondrosarcoma

Myeloma

Metastatic tumours

Rheumatological disorders

Ankylosing spondylitis

Rheumatoid arthritis

disorders of the lumbar spine: Pathology