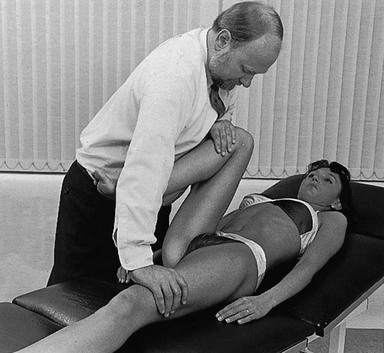

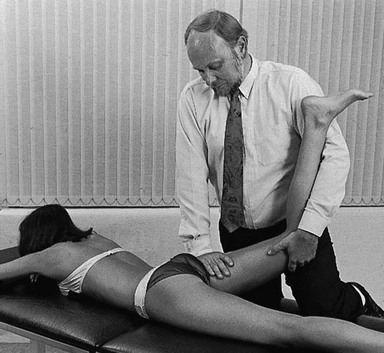

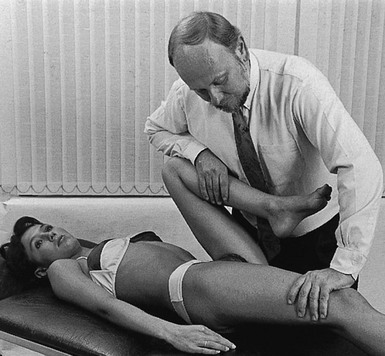

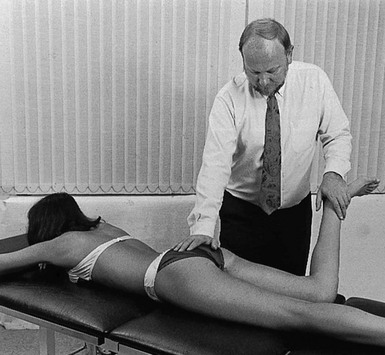

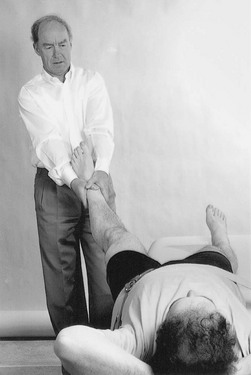

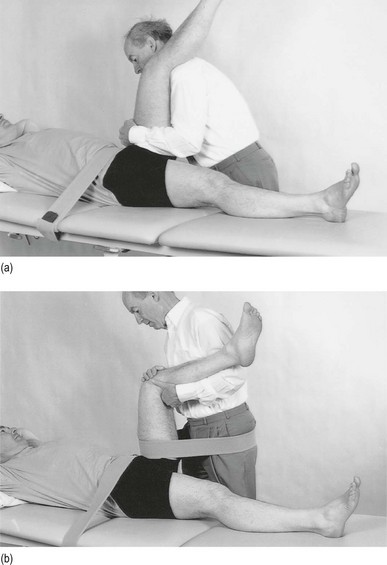

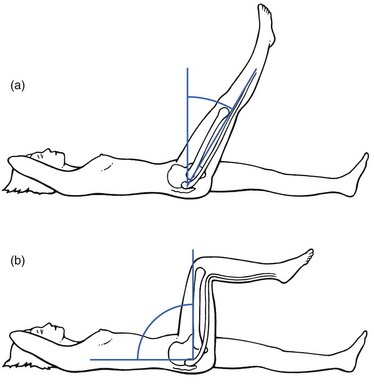

47 The capsular pattern at the hip joint is gross limitation of medial rotation, abduction and flexion, less limitation of extension, and little or no limitation of adduction and lateral rotation (Fig. 47.1). In advanced arthritis, abduction and internal rotation are impossible and associated with obvious limitation of flexion and extension. A capsular pattern in the hip joint of a child or adolescent always implies a serious problem. The slightest limitation of movement should be reason enough to put the child on bed rest and start diagnostic procedures to detect the cause. Weight bearing is prohibited until the reason for the capsulitis is discovered (see online chapter Hip disorders in children). This results more often from overuse of a stiffened and arthrotic joint than from a single injury. When it occurs in a child, transitory arthritis or the beginning of Perthes’ disease should always be suspected (see online chapter Hip disorders in children). In rheumatoid conditions, the hip is affected only late in the evolution of the disease. In polymyalgia rheumatica, both shoulders and hips are involved early in the course of the disease. Systemic therapy quickly relieves signs and symptoms.2 As a rule, this is caused by haematogenous dissemination, although it can also be the result of an intra-articular injection. Septic arthritis at the hip is not only a disaster for the joint but can also be life-threatening.3 Local aspiration should be carried out and systemic antibiotic therapy should be administered at once.4 This condition was described by Cyriax5 (his p. 386). For no special reason, a middle-aged patient experiences aching at the anterior aspect of the thigh during exertion. Clinical examination of the hip shows only a slight capsular pattern, with some limitation of internal rotation and flexion. There is pain at the end of range and the end-feel is elastic. The radiograph reveals nothing but a normal hip joint. The condition continues unchanged for months. Intra-articular injection with triamcinolone seems to be ineffective, but the lesion responds very well to stretching of the capsule, which relieves the pain quickly and permanently (see p. 633–634 for technique). It is widely accepted that the most likely causative factor in the development of arthrosis of the hip is the incapacity of (parts of) the hip to withstand mechanical stresses. In the literature, a distinction is made between primary and secondary arthrosis.6 When the osteoarthrosis results from an undetermined abnormality of the cartilage or the subchondral bone, the condition is called idiopathic or primary. Primary osteoarthrosis is extremely rare – in more than 90% of cases, previous abnormalities in the hip joint can be demonstrated.7–9 Strain may induce loss of proteoglycan molecules in the collagen network.10 This results in an increase in hydration and loss of tensile strength, and initiates the fibrillation of the cartilage.11,12 The health of articular cartilage depends largely on the mechanical qualities of its bony subchondral bed: the greater the discontinuity in elasticity between cartilage and subchondral bone, the more shear stress will occur.13 The presence of stiffened subchondral bone thus increases the likelihood of the progression of cartilage lesions.14 Inflammation of the synovial membrane can also be responsible for the degeneration of cartilage: connective tissue activating peptides and catabolites are set free during inflammatory reactions and have a negative influence on cartilage and subchondral bone.15,16 In addition, rigidity of the capsule, so often seen in the early stages of arthrosis,17 plays a role in its progression: because of the loss of laxity, the normal gliding movement of the cartilage surfaces is altered, which imposes a change in load distribution and thus increases stresses on particular areas of the joint. The composition of the synovial fluid may enhance the development of osteoarthrosis: a decrease in viscoelastic quality provokes more friction between the joint surface. It is well to remember that immobilization also decreases synovial fluid hyaluronan levels and may thus contribute to the progression of osteoarthrosis.18 Muscular dysfunction and disturbed neuromuscular balance are quite common in osteoarthrosis of the hip. They cause the joint to work under abnormal conditions and may play a role in the development or continuation of hip osteoarthrosis.19 A pattern of tightness and overactivity of the psoas, adductors, tensor fasciae latae and rectus femoris is typical in arthrosis of the hip joint, whereas the gluteals show a tendency towards weakness and inhibition.20,21 The continuous interaction between the changing structures of the joint imposes a physiological imbalance, which starts the process of degeneration. Vigorous and persistent attempts to repair the degenerative changes aggravate the already disordered joint function and set up a vicious circle. Hypervascularity, weakening of the subchondral bone, fatigue fractures, localized zones of collapse, flattening of the femoral head and formation of osteophytes then become inevitable (Fig. 47.3). This whole process can lead to rapid destruction of the joint; however, this is not always the case and spontaneous clinical and radiological improvements can occur.22 In the early stage, pain is only present during and after exercise but later it becomes continuous and can even disturb sleep. It is suggested that pain at night in coxarthrosis is associated with an increase in intracapsular pressure and subsequent joint contracture.23 If the patient mentions twinges during normal walking, the disorder is considered to be complicated by impacted loose bodies (see later). The examination often reveals a capsular pattern, with internal rotation the most limited and some limitation of flexion, extension and abduction, but this is certainly not always so. Many cases of hip osteoarthrosis present with other movement restriction patterns: for example, gross limitation of both internal and external rotation.24 As a rule, there is considerable difference between the clinical signs of an early osteoarthrosis and those found in advanced cases. In advanced instances, gross limitation is found, with loss of all rotational movement. In extreme cases, a ‘hinge joint’ develops, allowing only flexion and extension in an oblique plane: the femur moves laterally when flexion is forced. The end-feel is hard and marked coarse crepitus can be palpated. Muscle tightness can sometimes be detected by performing muscle length test procedures such as those described by Janda and Lewit.25–27 ‘Osteoarthrosis of the hip’ must be a clinical diagnosis and it is unwise to rely entirely on the radiograph for estimation of functional incapacity and for deciding on optimal treatment. First, there is a considerable lack of correspondence between the degree of pain, the mobility of the joint and the radiograph appearances.28 Second, the patient may suffer from other lesions at or around the arthrotic hip. These lesions – loose body, psoas or gluteal bursitis (see pp. 642–647) – are not radiographically visible. If a radiological examination is performed without a full history and proper clinical examination of the hip, such conditions will be missed and the painless arthrosis will be blamed for the pain. • Most osteoarthrotic hips show superolateral migration of the femoral head with localized erosion of cartilage at the lateral border of the labrum and a widening of the inferomedial part of the joint.29 Cameron and MacNab suggest that this is the form of osteoarthrosis that is primarily related to capsular restrictions and responds well to capsular stretching.30 • A medial–axial migration occurs in about 10–15% of cases. This presentation is usually associated with gross osteophytosis at the lower border of the femur and labrum. • Another 10–15% of cases are non-migratory hip osteoarthrosis, associated with superior or concentric loss of cartilage space and concentric formation of osteophytes (Fig. 47.4). Early treatment of osteoarthrosis is vital. There is evidence that reduced motion of the hip (from capsular tightening and muscular imbalance) further increases the degenerative process in cartilage and subchondral bone. Several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effect of exercise on pain and disability.31 The treatment of choice is therefore early stretching of the joint (grade B mobilizations). Treatment with injections has only a limited indication. In later stages or in quickly developing osteoarthrosis, conservative treatment is useless and surgery is indicated (Box 47.1). It is generally believed that early stretching of a tight capsule may prevent joint damage or at least slow further progression.32 Therefore, stretching is the treatment of choice in the early stage of the disease. The decision to use it depends largely on the clinical findings: early arthrosis with a slight capsular end-feel usually responds quite well to such treatment. Stretching is of no use in advanced arthrosis with gross limitation of movement, a hard end-feel and coarse crepitus because these are the clinical indications of gross cartilaginous destruction and formation of large osteophytes. The patient adopts a half-lying position on the couch. The therapist stands on the affected side, level with the patient’s knee. The hip is flexed as far as is comfortably possible. One hand rests on the anterior aspect of the knee, while the other presses the opposite thigh down towards the couch. With steadily increasing pressure applied to the knee, the thigh is forced towards flexion (Fig. 47.5). This position is maintained for as long as the patient can bear it: e.g. 1 minute. The pressure is then slowly released to give the patient a break and the same procedure is repeated. The patient lies prone on a high couch. The therapist stands level with the thighs. To prevent stress on the lumbar spine, it is vital to keep the patient’s pelvis on the couch when extension of the hip is forced. Therefore, with one hand, the therapist presses on the lower part of the buttock, which will obstruct movements at the lower back and the sacroiliac joint. With the other hand, the therapist grasps the thigh from the medial side, just above the patella. Both arms are kept rigid. Bending the body sideways, the therapist then pulls the patient’s thigh upwards, while the patient’s pelvis is pushed forcefully downwards (Fig. 47.6). Some elderly people have difficulty lying on their stomach for any length of time and an alternative method can be used. The patient lies flat on the back, with the head supported with a cushion. The painless hip is now forced as far into flexion as possible, which tilts the pelvis and makes the other thigh lift off the couch. Sufficient extension can now be forced when sustained downward pressure is applied just above the patella (Fig. 47.7). The patient adopts a prone-lying position on a high couch. The knee at the affected side is bent at a right angle. The therapist stands on the affected side and level with the pelvis. The ipsilateral hand is pressed on to the ilium. The other hand is placed at the medial malleolus and forces the hip into medial rotation. The pelvis rotates and moves the iliac crest backwards on the opposite side. Pressure applied on the pelvic region now forces the iliac crest downwards again. When the thigh on the affected side is held firmly in the rotated position, this downward pressure will considerably increase the outward stress on the affected hip (Fig. 47.8). Traction (either manual or mechanical) is an alternative technique to stretch the joint capsule.33–35 Traction is performed by leaning backwards with straight arms (Fig. 47.9). Once the therapist feels the patient relaxing the muscles, a jerk can be tried by pulling the arms towards the body. At this point, slight separation of the femoral head from the acetabulum can be felt. The therapist sits or stands at the level of the pelvis. The leg should be flexed to at least 90° and slightly laterally rotated. Both hands take hold of the upper part of leg (Fig. 47.10a). Traction is performed in the direction of the acetabulum: inferiorly, laterally and anteriorly. Use of a band makes it possible to lessen the effort of the therapist a great deal. Both hands then hold the leg in position at the knee (Fig. 47.10b). Traction is achieved by leaning backwards. Traction II is not suitable for manipulating the joint. In order to correct the pattern of muscular dysfunction and a disturbed neuromuscular balance, selective activation of inhibited, weak muscles and stretching of tight, shortened muscles is advocated by several authors.38–41 The second measure is of even greater importance because tight, hyperactive muscles interfere with the activation of inhibited muscles. These muscles (usually psoas, tensor fasciae latae and rectus femoris) are stretched slowly without straining the joint. Activation of inhibited muscles is achieved by exercises with low loads to prevent overflow into other muscles. It is also advisable to perform exercises as closely as possible to their functional manner. For this purpose, closed kinetic chain exercises are advocated because the weight-bearing component effectively stimulates mechanoreceptors around the joint, so improving muscular contractions.42 If the patient suffers from a subacute exacerbation because of traumatic arthritis superimposed on a stiffened arthrotic capsule, one intra-articular injection with 50 mg of triamcinolone will relieve the traumatic inflammation and the pain but increased mobility will not follow. To avoid arthropathy, this injection should not be repeated.43 Also, intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid seem to be a safe and effective method of treatment for patients with advanced hip arthrosis and may lead to a significant reduction in pain scores, disability scores and analgesic use.44–46 Total hip replacement is indicated in advanced osteoarthrosis. It is one of the most commonly performed operations in the United States, with over 280 000 procedures reported annually.47 The benefits of total hip replacement in terms of reduced pain and improved function and quality of life for patients with advanced coxarthrosis have been well documented in the literature.48 The prosthesis is made up of two parts: an acetabular component made of a metal shell with a plastic inner socket (the socket portion) that replaces the acetabulum, and a femoral component made of metal (the stem portion) that replaces the femoral head. The life expectancy of the prosthesis is between 15 and 20 years.49 Aseptic loosening with or without osteolysis is the major problem and accounts for 71% of the revisions, but the incidence had decreased three times during the past 15 years to less than 3% at 10 years in Sweden.50 However, long-term durability of the acetabular components remains a major concern.51 Concerns regarding high rates of failure among young, active patients and a desire to preserve bone for future revision operations led to the development of hip resurfacing arthroplasty. This differs from total hip replacement in that the femoral head is resurfaced rather than resected, thereby preserving femoral bone stock, which could theoretically decrease morbidity and improve patient outcomes associated with future revision operations.52,53 Serious lesions in the buttock are characterized by an interesting pattern of physical signs, called the ‘buttock sign’, summarized in Box 47.2. Non-capsular lesions of the hip itself comprise loose bodies, bursitis and aseptic necrosis of the femoral head. This clinical syndrome, described by Cyriax5 (his p. 375), always indicates a major lesion in the buttock. The buttock sign is characterized by more limitation and/or pain on passive hip flexion with a flexed knee than with an extended knee (i.e. straight leg raising; Fig. 47.11). The other passive movements at the hip joint are limited in a non-capsular way. This strange pattern immediately draws attention to the gluteal region. If the hip joint itself were affected, straight leg raising would not be limited, except in those gross articular patterns in which flexion cannot reach 90°. If the nerve roots, the sciatic nerve or the hamstrings were affected, hip flexion with a flexed knee would not be painful or limited because it does not stretch these structures. The fact that both movements are limited and painful implicates other structures in the gluteal region. Fig 47.11 The buttock sign: passive hip flexion is more limited and/or painful than straight leg raising. Checking for the buttock sign is very important in pain syndromes at the gluteal region. Because there will probably be nothing characteristic about the pain, only a comparison between the results of the straight leg raising test and passive hip flexion can detect serious disorders in the buttock.54–56 When this typical combination of signs emerges, a very careful examination of passive and resisted movements must follow. Passive movements disclose a non-capsular pattern, almost always with a full range of medial rotation. The end-feel of the limited movements is ‘empty’: as a consequence of the increasing pain, the examiner has to stop the movement, even though it is felt that the end of range has not been reached. Some resisted movements are painful and weak as well because they increase the tension on the affected tissues. As a rule, resisted extension and internal rotation are the most painful. Palpation may disclose a painful swelling. The patient’s gait is hobbling, as if the weight can hardly be borne on the affected leg.57 This major disability contrasts markedly with the minor degree of discomfort and is the first warning for the examiner. Occasionally, an anorectal abscess points towards the ischiorectal fossa instead of to the rectal region – an ischiorectal abscess.58 Sitting is impossible. The patient limps badly and even putting the foot to the ground causes considerable pain.59 The hip is held constantly in slight flexion but further flexion is prevented by increasing pain, as is straight leg raising, indicating the buttock sign. Apart from fever, other toxic symptoms may be present. The abscess may be felt during bidigital rectal examination with the index finger in the rectum and the thumb external. The treatment is surgical and consists of prompt incision and adequate drainage.60 Sacral fractures are associated with pain, swelling, ecchymosis and tenderness on palpation. In the presence of neurological symptoms, the diagnosis is usually not difficult. Neurological damage is not present, however, if the fracture line lies through the ala. Because of the position of the sacroiliac ligaments, the fracture remains stable and the diagnosis is then frequently missed.61 The patient may ascribe discomfort to local bruising and sometimes continues to be mobile. In a spontaneous sacral insufficiency fracture in an elderly woman the diagnosis is more difficult.62,63

Disorders of the inert structures

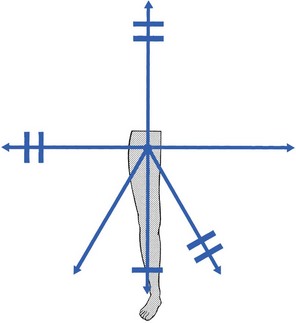

Capsular pattern

Traumatic arthritis

Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis

Rheumatoid conditions

Septic arthritis

Monoarticular arthritis in middle-aged people

Osteoarthrosis

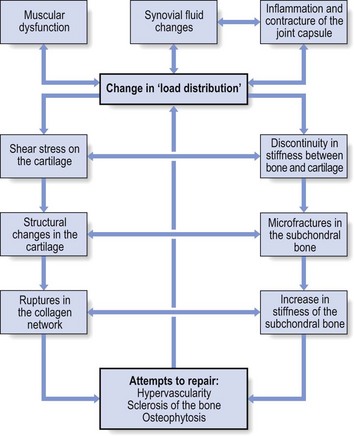

Aetiology

Cartilage fibrillation

Subchondral bone

Capsule of the joint

Synovial fluid

Muscular dysfunction

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms

Signs

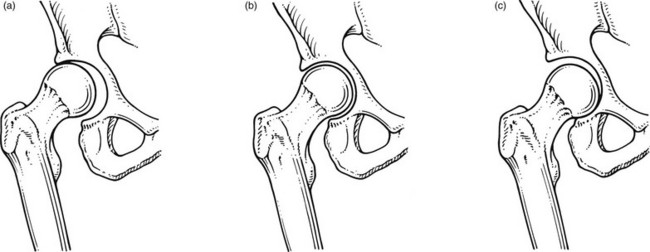

Radiography

Treatment

Capsular stretching

Technique: forced flexion

Technique: forced extension – 1

Technique: forced extension – 2

Technique: forced medial rotation

Traction

Traction I

Traction II

Muscular re-education

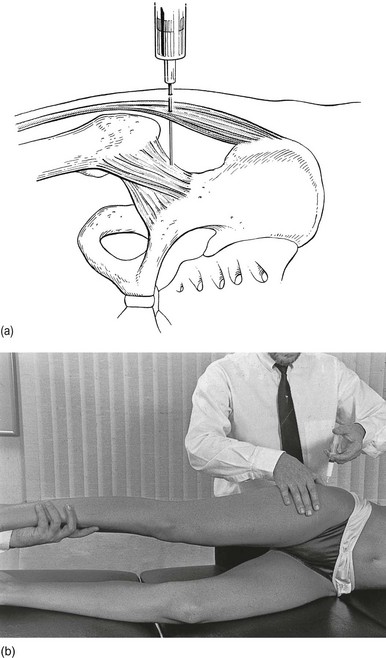

Intra-articular injections

Surgery

Non-capsular pattern

Disorders with a positive ‘buttock sign’

Septic bursitis

Clinical examination

Ischiorectal abscess

Fractured sacrum

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the inert structures