CHAPTER 25 Discography

INTRODUCTION

Discography was developed in the late 1940s for diagnosing lumbar intervertebral disc herniation.1,2 In contemporary practice, discography refers to provocation discography in which the most important component is the evaluation of pain reproduction caused by pressurizing the disc with contrast medium. Discography is conceptually an extension of clinical examination, tantamount to palpating for tenderness.3 A precision injection of contrast dye into the disc nucleus stimulates nerve endings4 (via two mechanisms: chemical stimulus from contact between contrast dye and sensitized tissues, and a mechanical stimulus resulting from fluid-distending stress).

Discography is a potential solution to the diagnostic dilemma concerning which patients to treat surgically and at what segmental level. In 1995, the North American Spine Society stated that discography, especially followed by CT scanning, may be the only study capable of providing a diagnosis or permitting precise description of the internal anatomy of a disc and the integrity of disc substructures.5 Although new diagnostic imaging tools have been developed and are widely used, discography is still practiced. Discography remains particularly useful in problematic cases unresolved by MRI or myelography and in patients for whom surgery is contemplated.6

In this chapter, the technical considerations and complications of discography are discussed.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

According to the position statement on discography by the North American Spine Society:5

PREPROCEDURAL EVALUATION AND PATIENT PREPARATION

Patient preparation

Since the disc is avascular, there is an increased risk of disc space infection and most discographers use prophylactic antibiotics.3 Animal studies have shown that intradiscal and intravenous antibiotics prevent discitis, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics 20 minutes prior to the procedure are recommended.7,8 In addition, many discographers add 2–6 mg/mL of a cephalosporin antibiotic to the nonionic contrast solution.8 All procedures should be performed under sterile conditions, including sterile scrub and double gloves.

TECHNIQUE OF LUMBAR DISCOGRAPHY

Disc puncture

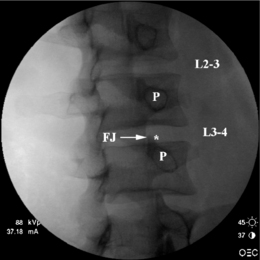

Prior to injection, a fluoroscopic examination of the spine is performed to confirm segmentation and determine the appropriate level for needle placement. Using AP view, the beam should be parallel to the inferior vertebral endplate. After selecting the target disc using AP view, the fluoroscopic beam is axially rotated until the facet joint space is located midway between the anterior and posterior vertebral margins. In this view, the insertion point is 1 mm lateral to the lateral margin of the superior articular process (Fig. 25.1).

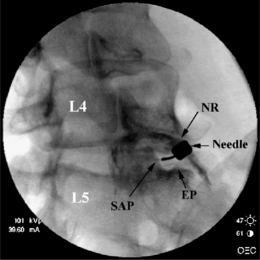

To avoid potential neural injury, the needle should be directed into the safe triangle. The borders of the safe triangle include the nerve root for the superior tangential border, the vertebral endplate of the target disc for inferior border, and the lateral margin of the superior articular process for the medial side line (Fig. 25.2). To minimize nerve trauma, one should use a needle with a short, noncutting bevel or blunt-pointed tip with a side port.

Puncture of T12–L1 through L4–L5 intervertebral discs

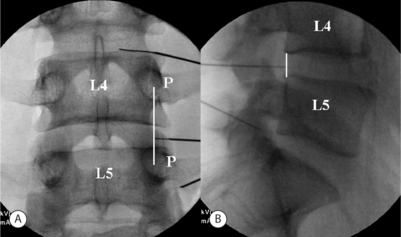

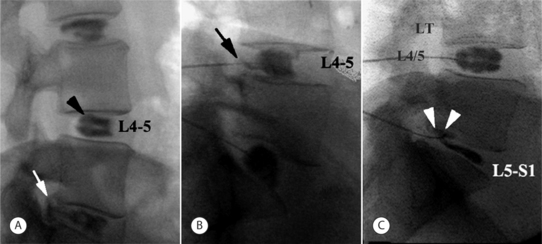

In the double-needle technique, a styletted 25-gauge, 6-inch needle is placed into each disc through a 20-gauge 3.5-inch introducer needle under fluoroscopic guidance. To protect the discographer’s hand from radiation exposure, forceps may be used to grasp the introducing needle. The introducer needle is advanced parallel to the fluoroscopic beam using an oblique fluoroscope view (Fig. 25.3).

A slight ‘hockey-stick’ bend at the end of the introducer needle can improve navigation. If bony obstruction is encountered, the physician should confirm whether the needle has contacted the superior articular process or the vertebral body. If necessary, the needle may be slightly withdrawn and its trajectory modified. The introducer needle can be either advanced just over the lateral edge of the superior articular process or advanced to the margin of the disc. At the L5–S1 level, advancement may proceed just over the lateral edge of the superior articular process. When the introducer or discogram needle contacts the disc margin, the ideal position in the AP projection is on a line drawn between the midpoints of the pedicles above and below (Fig. 25.4A).

In no case should one advance the introducer or discogram needle medial to the inner pedicle margins before contacting the intervertebral disc. In the lateral view the needle should contact the disc between the posterior vertebral margins (Fig. 25.4B).

L5–S1 intervertebral disc

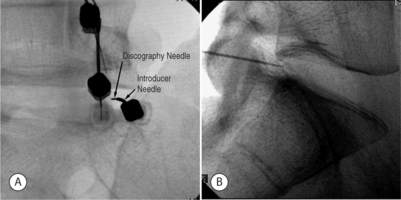

Due to increased facetal width and the presence of the iliac crest diacrest, puncture of the lumbosacral disc is more challenging. Instead of a direct lateral approach, once the introducer needle is advanced to the anterior border of the superior articular process of S1, a slight curve or ‘hockey-stick’ bend is needed to advance the discogram needle in a medial and slightly posterior direction around the SAP to contact the disc just anterior to the vertebral margin as viewed in the lateral fluoroscopy projection. Less experienced operators may find an 18/23-gauge needle combination easier to direct than the 20/25-gauge combination used for upper levels. Longer needle combinations may be required in muscular or obese patients. The fluoroscopy tube is rotated until about 1–2 cm of the L5–S1 disc is visualized between the superior articular process of S1 and the sacral ala (Fig. 25.2).

Using the oblique fluoroscopic view, the guide needle is introduced toward the bony notch between the sacral ala and superior articular process of S1 until the needle tip lies immediately adjacent to the anterolateral aspect of the superior articular process of the sacrum (Fig. 25.5A). The needle tip should not be handled directly, but should be wrapped in sterile gauze. The distal 2–3 cm of the needle should be bent in a direction opposite the bevel. The degree of curve is determined by the operator on the basis of how much deflection is required in the patient at hand for the needle to approach the target disc center. In a lateral fluoroscopic projection, the 25-gauge discogram needle is passed through the guide needle while the guide needle is held firmly in position. The inner needle is advanced until the tip emerges from the guide needle. The inner needle is advanced under direct fluoroscopic vision. As it emerges, the guide needle is retracted slightly (Fig. 25.5A). This unsheathes the procedure needle, which should be turned so that the curve or bend bows the introducer needle in a medial and posterior direction through the safe triangle. Once the needle encounters the anulus fibrosus, its position is checked and confirmed in both AP and lateral fluoroscopy views. In the lateral view the needle should contact the disc 2–3 mm anterior to the vertebral margin (Fig. 25.5B) and in the AP view the needle should ideally be on a line bisecting the midpoint of the L5 and S1 pedicles.

Provocation using pressure manometry

Imaging

The appearance of the normal nucleus following the injection of contrast medium is unmistakable: the contrast medium assumes a lobular pattern or a bilobed ‘hamburger’ pattern (Fig. 25.6A). A variety of patterns may occur in abnormal discs.9 Contrast medium may extend into radial fissures of various lengths but remain contained within the disc (Fig. 25.6B), or it may escape into the epidural spaces through a torn anulus (Fig. 25.6A). In some cases (Fig. 25.6C), the contrast medium may escape through a defect in the vertebral endplate.3 However, none of these patterns alone is indicative of whether the disc is painful; that can be ascertained only by the patient’s subjective response to disc injection.

Immediately after discography, CT–discography may be performed to define fissures extending to the outer third of the anulus and extending circumferentially within the anulus fibrosus. Radial annular tears can be found by discography, but only the postdiscogram CT axial view clearly shows the location and size of fissures within the anulus fibrosus.3 Sachs et al.10 developed the Dallas discogram scale, in which annular disruption is graded on a 4-point scale. Grade 0 describes contrast medium contained wholly within a regular nucleus pulposus. Grades 1 to 3 describe the extension of contrast medium along radial fissures into the inner third, middle third, and outer third of the anulus fibrosus, respectively. Aprill and Bogduk11 proposed a modified Dallas description scale which includes grade 4, distinguished from grade 3 by the spread of contrast medium circumferentially within the substance of the anulus fibrosus and subtending a >30° arc at the disc center.

Interpretation

Adding pressure monitoring to provocative discography improves interobserver reliability and, as a result, reproducibility. A positive discogram requires an abnormal disc, pain response =6/10 (numeric rating scale; NRS), pressure level =50 psi, pain described by the participant as ‘familiar,’ and at least one negative control disc. One must, however, be aware that transient pain is often provoked when fissures are suddenly opened. In most cases, such pain should not be used as evidence of a true-positive response unless pain >6/10 is sustained for more than 30 seconds. Most experienced discographers will perform a confirmatory re-pressurization once a suspected positive response is provoked. If re-pressurization does not again provoke significant concordant pain at 50 psi or less above opening pressure, then the initial response will remain indeterminate. These criteria for positive response were reconfirmed in a study performed in 13 normal asymptomatic volunteers.11a,11b When the operational criteria for discography were set to pressure =50 psi and evoked pain intensity >4, the expected false-positive rate was <10%. However, a false-positive rate of zero could be secured either if the pain score was held at 4 and the injection pressure lowered to 20 psi, or if the pressure was held at 50 psi and the required pain score was raised to 6. To increase discography specificity, local anesthetic may be injected into the positive disc in an effort to obtain prolonged relief of pain from that disc (analgesic discography). In a preliminary study investigating the reliability of analgesic discography, 78% of patients showed significantly prolonged pain relief after local anesthetic injection. Those patients underwent fusion surgery and were followed to observe surgical outcome (T. Alamin, personal communication, 2004).

In addition to these criteria for positive discography, disc anulus sensitivity may also be graded. Using the protocol of Derby et al.,12 four disc categories may be defined: (1) chemical discs, which provoke pain at 15 psi above opening pressure, (2) mechanical discs, which provoke pain at pressures between standing and lying, or 15–50 psi above opening pressure, (3) indeterminate discs, which provoke pain at 51–90 psi above opening pressure, and (4) normal discs, with no pain provocation. If a disc is painful at >50 psi, the response cannot be considered clinically significant, since it is difficult to distinguish from the effect of mechanically stimulating a normal or subclinically symptomatic disc.13 Excessive stimulation involving pressures >50 psi above opening pressure and uncontrolled, high injection speeds increase false-positive responses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree