Digital and Sesamoid Fractures

Michael S. Downey

Stephanie Comer Merritt

Carolyn J. Sharrock-Maher

Marc R. Bernbach

Digital and sesamoid fractures are common injuries affecting all age groups, even those patients who are sedentary. In most circumstances, the fractures are amenable to conservative treatment and generally do not pose a problem. However, many patients who have sustained a digital fracture do not seek care for their injury in an expedient manner and thus render what would otherwise be a simple yet inconvenient problem more difficult to treat and prolong the recovery period. A certain mindset seems to exist among many lay people that there is really no specific treatment for digital fractures, and this attitude likely contributes to the delay between injury and seeking treatment.

However, significant fractures may affect the digit and may require more prompt attention, particularly if dislocation or displacement occurs or if the fracture is open. In most injuries of this nature, deformity is obvious, and patients tend to seek treatment quickly.

DIGITAL FRACTURES

As with any injury, the pathologic forces that cause digital fractures may be directed in any one or a combination of the cardinal body planes. Although most injuries involve a combination of these forces, a predominant plane of force can often be identified. Certain fracture patterns are more frequently observed and can be related to these injury mechanisms. Understanding the predominant plane of injury facilitates reduction, realignment, and treatment of digital fractures.

Sagittal Plane

Injury occurring in the sagittal plane and resulting from direct trauma, hyperextension, or hyperflexion of the involved digit is the cause of most digital fractures. Sagittal plane crushing is the most frequent mechanism of injury associated with a fractured hallux. Crush injuries are most often caused by a heavy object, which may be dropped or may fall, or by industrial or motor vehicle accidents. A subungual hematoma is often a component of the injury. Protocols for care of the nail injury can be found in Chapter 18. The digital fractures seen in direct traumatic injuries are frequently comminuted and most commonly involve the phalanges of the hallux and the middle and distal phalanges of the lesser digits (1, 2, 3).

Transverse Plane

Abduction-adduction forces are also common and generally result in transverse or short oblique fractures of the proximal phalanges. The most notorious example of this injury has been termed the bedroom fracture because it often results from striking the fifth digit against a bedpost while the patient is walking in the dark (Fig. 1). At times, the injury may consist of a dislocation of the interphalangeal joint or the lesser metatarsophalangeal joint. Even though the proximal phalanx of the fifth digit is the most commonly involved, other digits may be injured through abduction or adduction forces. A transverse fracture free from the articular surfaces may be treated with closed reduction, whereas comminuted or open fractures may require surgical intervention.

Frontal Plane

Rotational or inversion-eversion injuries occurring predominantly in the frontal plane are less frequent and generally are secondary components of transverse or sagittal plane fractures. When spiral fractures of the phalanges occur, closed reduction is more difficult, as is maintaining the reduction once it has been achieved, because the more unstable nature of the fracture pattern.

Clinical Presentation

The signs and symptoms of digital fractures consist of pain, ecchymosis, and edema that develop within a few hours

after injury. The patient experiences acute pain, has difficulties with weight bearing, and finds wearing shoes that compress the area uncomfortable. In some instances, an obvious clinical deformity is seen in the digit as a result of displacement of the fracture. Other patients may relate that they relocated the deformed toe themselves after the injury.

after injury. The patient experiences acute pain, has difficulties with weight bearing, and finds wearing shoes that compress the area uncomfortable. In some instances, an obvious clinical deformity is seen in the digit as a result of displacement of the fracture. Other patients may relate that they relocated the deformed toe themselves after the injury.

Treatment

Closed Injuries

The initial evaluation is directed toward assessing the neurovascular status of the toe or toes and evaluating the degree of tissue compromise and clinical deformity. Two to three radiographic views are adequate to demonstrate the injury in most cases.

The treatment methods of closed digital fractures range from simple protection of the toe to surgical reduction or excision of all or some of the fracture fragments. Treatment of closed digital fractures may be divided into criteria based on several factors, including the following: (a) alignment of the fracture fragments; (b) if malaligned, the possibility that the fragments can be adequately realigned with closed reduction; and (c) the possibility that alignment can be maintained once the fragments are reduced. Reduction of the fracture is performed in an attempt to prevent shortening, angulation, and rotational malalignment.

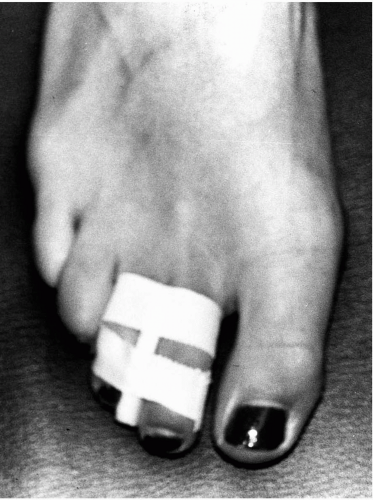

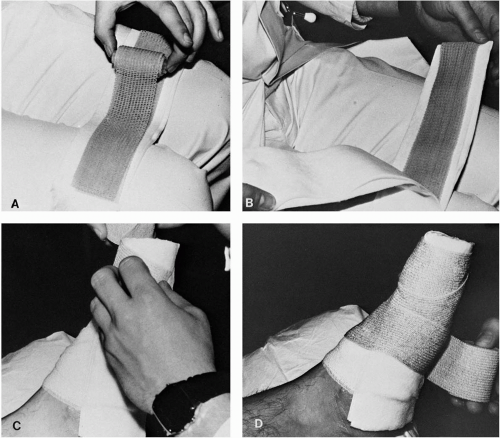

Protection alone consists of maintaining stability to the injured region with immobilization. Comfort and stability may be enhanced by splinting the injured digits to the uninjured neighboring toes with tape, felt, silicone molds, urethane molds, prefabricated digital splints, or other similar materials. This method of splintage is termed buddy splinting (Fig. 2). A splint or rigid material can be formed around the hallux and secured along the medial aspect of the foot for phalangeal fractures of the hallux (Fig. 3). After splintage, the injured foot can be additionally protected with a surgical shoe or in a non-weight-bearing position if necessary. Most phalangeal fractures are immobilized in the position of function, and the duration of immobilization is determined by clinical and radiographic evidence of healing. In most cases, consolidation of the osseous fragments develops in 4 to 8 weeks. During this period, the clinician must correlate the clinical findings with radiographic evidence because fracture lines will remain radiographically visible for several months.

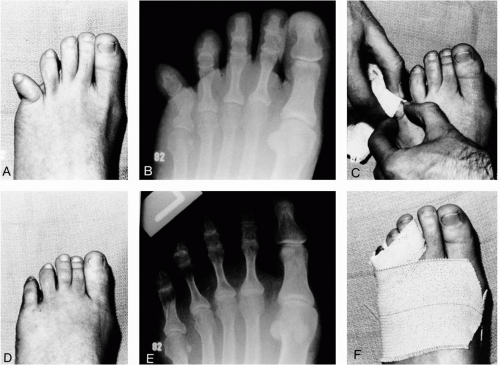

The alignment of the fracture fragments is the key in determining whether reduction is necessary. It is important to understand the principles of closed and open reduction as well as the anatomy and the mechanism of injury if malalignment exists. Bone injury is less significant than the soft tissue disruptions that occur on the convex side of the fracture site. Generally, the soft tissues on the concave side of the injury remain intact. These soft tissue structures guide the fracture fragments into a more normal position and tend to prevent overcorrection during closed reduction by acting as a hinge on the concave surface. Manipulative reduction is achieved, exaggerating the plane of deformity, followed by distraction and then reduction. After completion of the reduction, radiographs

are made to assess alignment (Fig. 4). The configuration of the fracture may be described as stable, potentially stable, and unstable. Stable, reduced fractures are able to withstand telescoping forces with protection and immobilization and are generally transverse in orientation to the longitudinal axis of the bone or a short oblique phalangeal fracture. Both fracture types are usually treated with closed reduction and immobilization and typically respond well and heal without adverse sequelae unless the injury has an intraarticular component. In this circumstance, the patient may later develop stiffness or painful arthrosis even if healing progresses uneventfully.

are made to assess alignment (Fig. 4). The configuration of the fracture may be described as stable, potentially stable, and unstable. Stable, reduced fractures are able to withstand telescoping forces with protection and immobilization and are generally transverse in orientation to the longitudinal axis of the bone or a short oblique phalangeal fracture. Both fracture types are usually treated with closed reduction and immobilization and typically respond well and heal without adverse sequelae unless the injury has an intraarticular component. In this circumstance, the patient may later develop stiffness or painful arthrosis even if healing progresses uneventfully.

Unstable fractures possess minimal intrinsic ability to withstand shortening and consist of long oblique, spiral, or some comminuted fractures. Creating adequate stability may require additional support from external fixation or open reduction with fixation. Kirschner wires can be inserted percutaneously to maintain a fracture that has been realigned with closed reduction. Serial postreduction radiographs or fluoroscopy may be used to ascertain proper placement and reduction. Direct open reduction with the wires may prove necessary in some instances.

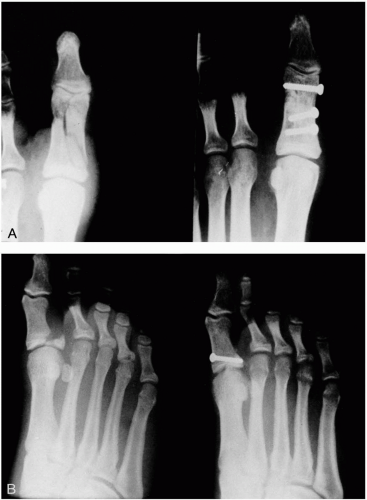

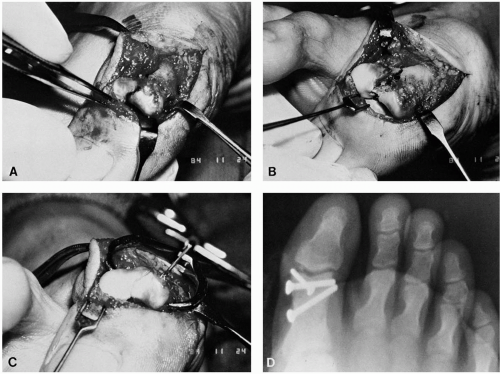

Fractures that are unstable, nonreducible, intraarticular, or associated with coexisting neurovascular compromise need immediate attention and may require open reduction with fixation for proper alignment and stability. Surgical intervention with open reduction is performed with standard sterile technique and insertion of appropriate hardware as deemed necessary (Fig. 5). Achieving proper fixation is required, especially with intraarticular fractures that have a significant potential to develop posttraumatic arthritis, as seen in fractures of the hallux interphalangeal joint (4) (Fig. 6).

In the lesser digits, the concern for complete reduction of the intraarticular components of the fracture is not as great. Stiffness or arthrosis is generally not as disabling as in the hallux interphalangeal joint, the lesser toes are not subjected to the same degree of weight-bearing stress, and surgical options for repair of these digits are generally easily accomplished. Infrequently, comminuted fractures of the lesser digits may require excision of the fragments because of the numerous minute fractures. Excision may be carried out immediately in patients with traumatic open fractures or later with closed fractures if fragments become symptomatic after conservative treatment has failed. If painful arthrosis or malunion of the bone persists, resectional arthroplasty of the involved joint may be necessary (5).

Even with proper immobilization and fixation, posttraumatic sequelae may occur with digital fractures. Included in the potential long-term problems are delayed union or nonunion of the fractured segments, malunion, chronic pain, and posttraumatic intraarticular arthrosis. In these instances, surgical intervention, possibly including arthroplasty or arthrodesis, may be necessary to obtain pain relief for the patient (4, 5, 6, 7).

Open Injuries

Open injuries frequently represent a surgical emergency. One should initially evaluate the neurovascular status of the injured part as well as the extent of any soft tissue loss (Fig. 7). Specimens for Gram’s stain and culture should be taken from the wound. Multiple radiographs aid in assessing the bone disruption. Thorough irrigation is then necessary to reduce the risk of infection. The wounds may then be evaluated relative to repair of the injuries and soft tissues.

SESAMOID FRACTURES

Anatomy

The sesamoid bones of the hallux are located at the plantar aspect of the first metatarsophalangeal joint and are embedded within a fibrous tendoligamentous network. No periosteum surrounds the sesamoid, but rather an aponeurosis surrounds the plantar cortex (8,9). A cartilaginous dorsal surface articulates with the first metatarsal head (10). This is believed to increase the mechanical leverage of the great toe by acting as a fulcrum for the flexor tendons.

Initially, the sesamoids become identifiable as undifferentiated connective tissue within the tendon of the flexor hallucis brevis by the eighth week of embryonic life, and chondrification arises during the twelfth week of gestation. Ossification usually occurs between 8 and 10 years of age. The multiple foci of ossification may or may not coalesce leading to bipartite, tripartite, or quadripartite sesamoid bones. The incidence of bipartite sesamoids varies widely. Kewenter reported a 35.5% incidence in 1,588 feet, and Inge and Ferguson stated a 10.7% incidence in 1,025 feet, with 75% of cases being unilateral (11). Both studies described numerous variations in partite sesamoids (Fig. 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree