Diastasis of the Symphysis Pubis: Open Reduction Internal Fixation

David C. Templeman

Matthew D. Karam

INTRODUCTION

Diastasis of the pubic symphysis is often part of a complex injury to the pelvic ring. The bony pelvis provides protection to the lower abdominal and genitourinary tract as well as the great vessels of the pelvic floor and lower extremity. High-energy trauma that leads to disruption and displacement of the pelvis may lead to deformity, instability, and associated injuries to the surrounding visceral structures. In a small but not insignificant number of patients, serious or life-threatening hemorrhage may occur. Inadequately diagnosed or treated, these injuries can result in residual pain, leg length discrepancy, limp, sitting imbalance, and sexual or bladder dysfunction.

Ligamentous symphyseal disruptions heal less predictably than parasymphyseal fractures and can be a source of chronic pain if not appropriately treated. Due to the close proximity of the anterior pelvic ring and genitourinary tract, injuries to the bladder and urethra occur in up to 25% of patients. These associated injuries increase both the morbidity and mortality following pelvic fractures involving the anterior pelvic ring.

Several different classifications can be used to characterize pelvic injuries. Early classifications were based on either the location of the fracture or the mechanism of injury. Most modern classifications, however, are based on the degree of pelvic stability (1,2). The Tile classification of pelvic ring injuries is used to predict the mechanical instability of the injured pelvic ring and is categorized as A, stable; B, rotationally unstable but vertically stable; and C, rotationally and vertically unstable. Tile B and C injuries may have associated disruption of the symphysis pubis (2). The Young and Burgess modification of the Tile classification is based on the mechanism of injury. This system categorizes Tile B injuries that are rotationally unstable as APC I, which have a symphyseal disruption of <2.5 cm and APC-II injuries with >2.5 cm of symphyseal diastasis, both of which have intact posterior sacroiliac ligaments and are vertically stable. With more severe injuries and increasing external rotation, the posterior ligaments are ruptured resulting in vertical and rotational instability, which is classified as an APC-III injury or Tile C injury.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous joint where the pubic bones meet. The articulation is composed of a fibrocartilaginous disc that is reinforced by the superior and inferior pubic ligaments. The arcuate ligament forms an arch between the two inferior pubic rami and is thought to be the major soft-tissue stabilizer of the symphysis pubis (3).

Injuries to the pubic symphysis include diastasis, fractures into the symphysis, and fracture dislocations. Following trauma, if the pubic symphysis is not disrupted, the anterior pelvic-ring injury commonly consists of

pubic rami fractures. These fractures are usually vertically oriented but may be comminuted or horizontal (4). Diastasis of the symphysis pubis rarely coexists with fractures of the pubic rami (5,6).

pubic rami fractures. These fractures are usually vertically oriented but may be comminuted or horizontal (4). Diastasis of the symphysis pubis rarely coexists with fractures of the pubic rami (5,6).

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually indicated when diastasis of the pubic symphysis exceeds 2.5 cm. Displacement of this magnitude is thought to be accompanied by injuries to the sacrospinous ligament and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments, which allow the involved innominate bone to rotate externally; however, recent cadaveric studies indicate that these ligaments often remain intact (7). Stable fixation of the symphysis is sufficient to correct this instability (4). Internal fixation is performed to relieve pain and improve stability of the anterior pelvic ring. The indications for surgery are based on the patient’s overall condition and the stability of the entire pelvic ring.

In Tile C or Young-Burgess APC-III injuries, the symphysis pubis (or the anterior pelvic ring) is disrupted as is the posterior pelvic ring, resulting in complete instability of the pelvis. Fixation of the anterior ring alone is insufficient to restore pelvic stability and must be accompanied by reduction and fixation of the posterior pelvic injury (2,8).

The differential diagnosis of an APC-III versus an APC-II is therefore critical in deciding when to proceed with fixation of the posterior pelvic ring. When the posterior sacroiliac ligaments are intact (APC-II Injury/Tile B), the external rotation of the innominate bone is accompanied by inferior displacement of the pubic bone due to the geometry of the sacroiliac joint. This inferior displacement helps to differentiate an APC-II injury from vertical displacement of the pubic body that usually occurs with APC-III injuries. This sign has been verified by both clinical observations and laboratory studies in cadaveric specimens. An additional clue to the presence of an APC-III injury is cranial displacement of the ischial tuberosity on the injured side.

Contraindications to internal fixation of the symphysis pubis include unstable, critically ill patients; severe open fractures with inadequate wound débridement; and crushing injuries in which compromised skin may not tolerate a surgical incision. Suprapubic catheters placed to treat extraperitoneal bladder ruptures may result in contamination of the retropubic space and are a relative contraindication to internal fixation of the adjacent symphysis pubis. Obese patients (BMI > 30) who undergo pelvic fixation have a substantial increased risk of complications including wound dehiscence, loss of reduction, iatrogenic nerve injury, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pneumonia, and development of decubitus ulcers (9). Additional conditions that may preclude secure fixation are osteoporosis and severe fracture comminution of the anterior pelvic ring.

When the diastasis of the symphysis pubis is <2.5 cm, internal fixation is seldom necessary. Patients may be safely mobilized and allowed to exercise toe-touch weight bearing on the side of the externally rotated hemipelvis. Radiographs are repeated within the first few weeks to ensure further displacement has not occurred. By 8 weeks, the pelvis is usually healed enough to allow full weight bearing.

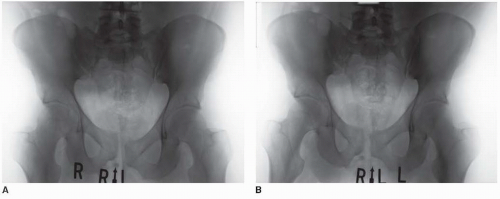

Chronic pelvic-ring instability may follow nonoperative treatment or unrecognized pelvic-ring injuries. This subset of patients commonly presents with pain in the symphyseal or sacroiliac region when undergoing weight-bearing activities. For this group of patients, single-leg-stance radiographs may be useful. The radiographs are taken as standard anteroposterior (AP) pelvis x-rays, and the three-film series should include a standing AP pelvis as well as an AP of the pelvis during left leg stance and an AP of the pelvis during right leg stance. Subtle instability may manifest as a vertical displacement at the symphysis pubis with single leg stance on the unstable side (Fig. 38.1). These chronic instabilities may be approached with the same technique of fixation that one would use to treat an acute injury, but retropubic scarring of the bladder to the posterior aspect of the pubic bones and symphysis may be encountered.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History and Physical Examination

The mechanism of injury should be determined because the initial evaluation and treatment differ dramatically in patients with lower-energy injuries that occur following a mechanical fall from those the result from high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents or falls from a height. Elderly patients with compromised bone who sustain ground-level falls usually result in a hip fracture. However, a subgroup of these patients sustain pubic rami fractures, which can be very painful. Alternatively, patients with high-energy trauma and pelvic disruption require evaluation and treatment using Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols. Patients with hemodynamic instability require urgent evaluation and resuscitation. A multidisciplinary team consisting of general surgeons, orthopedists, urologists, and interventional radiologists is frequently required to treat patients with multiple injuries (10, 11, 12 and 13).

Because the spectrum of injuries to the pelvis is so great, the physical examination ranges from mild focal tenderness to massive swelling, skeletal distortion, and pelvic instability. The skin should be inspected for abrasions, degloving injuries (Morel-Lavelle lesions), and open wounds. The integrity of femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses must be determined. A thorough neurologic examination should be performed and documented. A rectal exam with evaluation of the prostate is necessary in complex fracture patterns as is a vaginal pelvic examination in females. A one-time assessment of pelvic stability should be carried out by a senior, experienced trauma specialist.

Imaging

After the patient has been stabilized, radiographic studies are obtained. To determine the direction and magnitude of the symphysis pubis disruption and the relative position of the pubic bones, the surgeon should obtain AP, 40-degree caudal and 40-degree cephalad views (Fig. 38.2A-C). Differences in the height of the pubic rami usually indicate that the hemipelvis is displaced in more than one plane. The most common deformity associated with disruption of the symphysis pubis is cephalad migration, posterior displacement, and external rotation of one hemipelvis (1). This pattern indicates a posterior pelvic injury (Tile C/Burgess APC III) that requires posterior reduction and internal fixation to achieve a stable pelvis (2,8,14). In addition to the plain films, a computed tomography scan is recommended to assess the posterior pelvic anatomy. The anterior structures are best studied with plain films (2,12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree