CHAPTER 6 Diagnostic Imaging of the Elbow

INTRODUCTION

Imaging technology has expanded dramatically over the past decade (Box 6-1). However, evaluation of the elbow still relies heavily on routine radiographs or computed radiography (CR) images. Optimal hard copy radiographs, or CR images, are essential to properly select additional studies and are required for accurate interpretation of other modalities such as magnetic resonance (MR) imaging.7

Conventional tomography is rarely performed today. However, computed tomography (CT) has increased in utility with new multidetector systems that provide rapid evaluation of numerous bone and soft tissue disorders.3 Arthrography also can be an important tool in the diagnosis of intra-articular disorders of the elbow. Today, conventional, CT, and MR arthrography play important roles for evaluating the articular cartilage, intra-articular anatomy, and supporting structures of the elbow.7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) frequently is used to evaluate subtle osseous and soft tissue abnormalities. Soft tissue contrast is superior to that achieved with CT. MRI scans can be obtained in any plane, which is an additional advantage. Intravenous or intra-articular injection of gadolinium provides additional information in selected cases.23

RADIOGRAPHY/COMPUTED RADIOGRAPHY IMAGING

An understanding of the process by which routine radiographs or CR images are obtained is essential. Factors such as the type of equipment, patient positioning, and radiation dose must be kept in mind when determining the necessary views in a given clinical setting. In obtaining views of the elbow, we routinely use a 48-inch target film distance with 50 to 60 kVp, 600 ma, and an exposure time of 0.0125 seconds. Reusable CR or regular cassettes measuring 10 × 12 inches are routinely employed.1,4,5

A minimum of two projections is necessary for evaluation of the elbow. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the elbow are taken at 90-degree angles and fulfill these criteria. In trauma patients, we routinely obtain oblique views as well.1,5

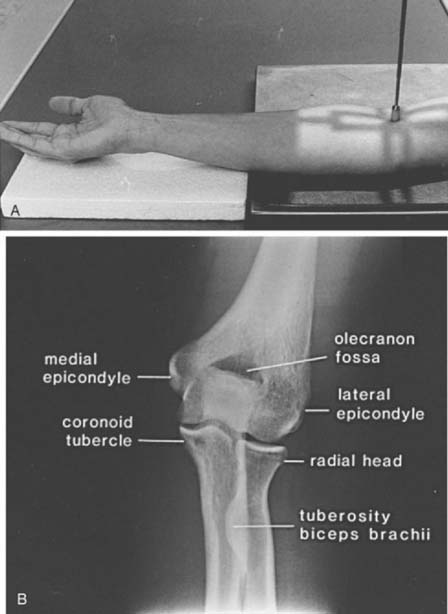

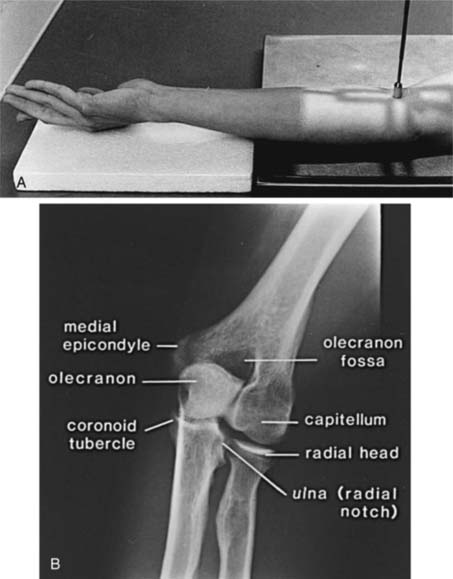

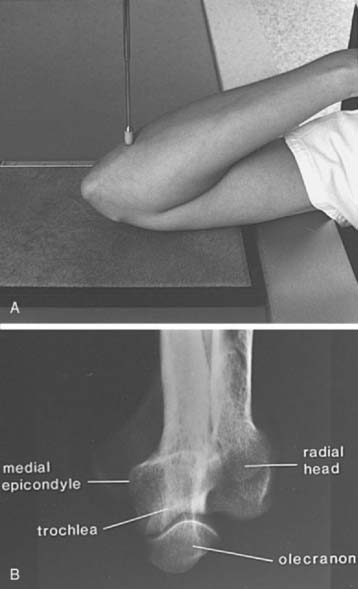

ANTEROPOSTERIOR VIEW

The AP view (beam enters the patient anteriorly and the film is posterior) is obtained by placing the patient adjacent to the radiographic table in a sitting position (the supine position may be used if the patient is injured). The patient should be positioned with the extended elbow at the same level as the cassette so that the extremity is in contact with the full length of the cassette.1,4 The hand is supinated, and the beam is centered perpendicular to the elbow (Fig. 6-1A). The AP view demonstrates the medial and lateral epicondyles and the radiocapitellar articular surface (Fig. 6-1B). Assessment of the trochlear articular surface and at least a portion of the olecranon fossa is also possible. The normal carrying angle (5 to 20 degrees, average 15 degrees) can be measured on the AP view.1,5

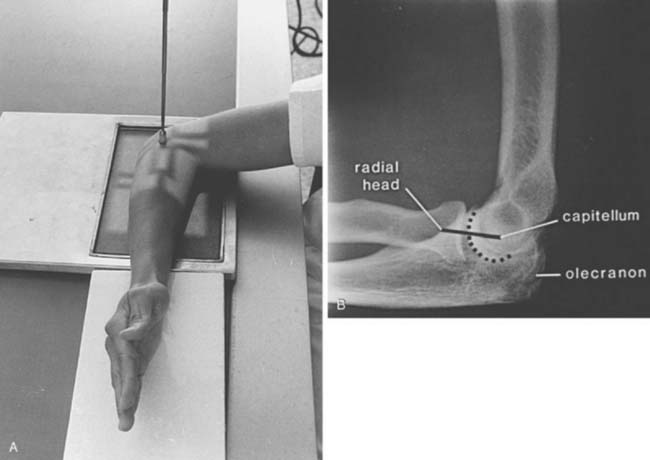

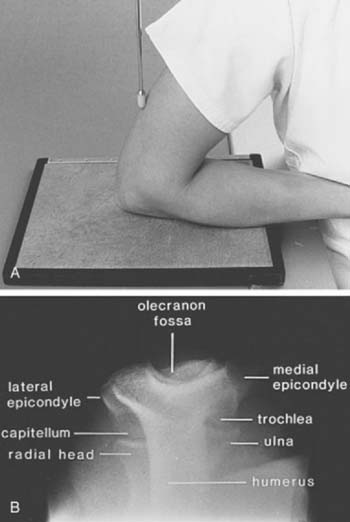

LATERAL VIEW

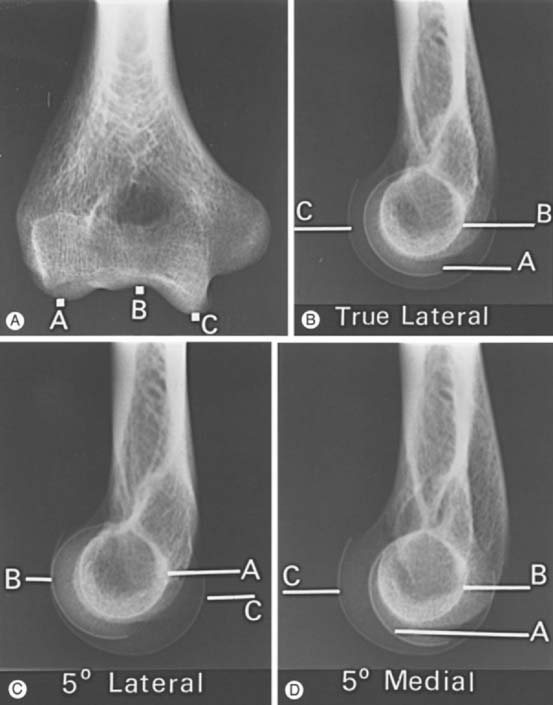

The lateral view is obtained by flexing the elbow 90 degrees and placing it directly on the cassette. The hand is positioned with the thumb up so that the forearm is in the neutral position; the beam is perpendicular to the humerus (Fig. 6-2A). This view provides good detail of the distal humerus, elbow joint, and proximal forearm. The coronoid of the ulna, which cannot be readily seen on the AP view, and the olecranon are well visualized on the lateral view (see Fig. 6-2B). Because the articular surface makes a valgus angle of about 7 degrees to the long axis of the humerus (see Chapter 2), a lateral view of the arm does not provide a lateral view of the joint. If the x-ray beam is parallel to the articular surface, three concentric arcs can be identified (Fig. 6-3A-D).5 The smaller arc is the trochlear sulcus, the intermediate arc represents the capitellum, and the largest arc is the medial aspect of the trochlea. If the arcs are interrupted, a true lateral view has not been obtained. Unfortunately, in patients with acute injury, true AP and lateral views are often difficult to obtain. Patients are frequently unable to extend or flex the elbow fully. In these situations, the tube must be angled and the cassette positioned to simulate these views as closely as possible.1,4,5

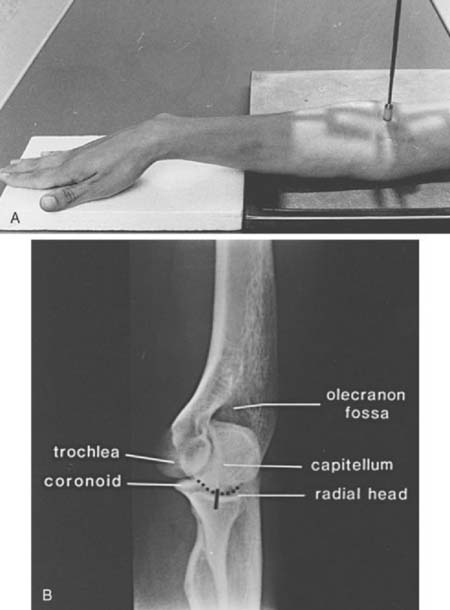

OBLIQUE VIEWS

Oblique views are obtained by initially positioning the arm as if one were taking the AP view. For the medial oblique projection (Fig. 6-4A and B), the arm is positioned with the forearm and arm internally rotated approximately 45 degrees (see Fig. 6-4A). This view allows improved visualization of the trochlea, olecranon, and coronoid (see Fig. 6-4B). The radial head is obscured by the proximal ulna. The lateral oblique view is taken with the forearm, hand, and arm rotated externally (Fig. 6-5A). This projection provides excellent visualization of the radiocapitellar joint, medial epicondyle, radioulnar joint, and coronoid tubercle (see Fig. 6-5B).1,4,5

RADIAL HEAD VIEW

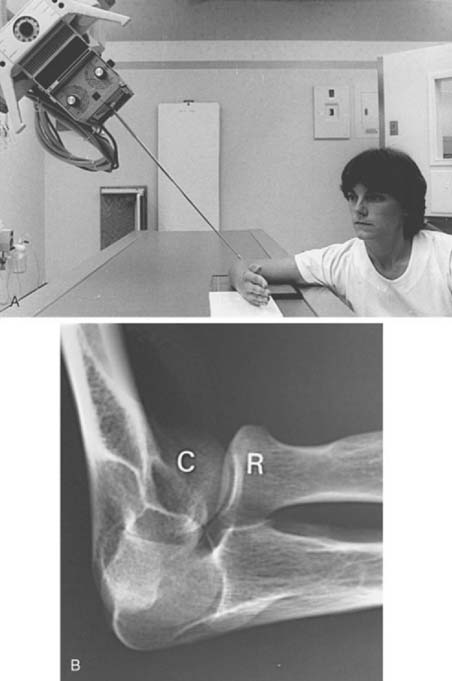

Radial head fractures are a common clinical problem and are often difficult to visualize on radiographs or CR images. The radial head view may define the fracture more clearly.16,17,28 This view (Fig. 6-6A and B) is easily accomplished by positioning the patient as one would for the routine lateral view. The tube is angled 45 degrees toward the shoulder joint (see Fig. 6-6A). The radial head view projects the radial head away from the ulna, allowing subtle changes to be more easily identified (see Fig. 6-6B), and it also may allow better visualization of the fat pads.1,16,17

FIGURE 6-6 Radial head view. A, The patient is positioned as if a routine lateral view (see Fig. 6-2A) were to be obtained. The tube is angled 45 degrees toward the humeral head rather than perpendicular to the joint. B, Radial head view projects the radial head (R) clear of the olecranon and clearly demonstrates the capitellum (C) and radiocapitellar joint.

AXIAL VIEWS

Occasionally, suspected pathology of the olecranon or epicondyles prompts further evaluation with axial views. Figure 6-7A and B demonstrate the axial projection used to evaluate the epicondyles, olecranon fossa, and ulnar sulcus. The patient’s elbow is flexed approximately 110 degrees, with the forearm on the cassette and the beam directed perpendicular to the cassette. This view is also helpful in detecting subtle calcification in patients with tendonitis. The olecranon process may be better observed on the reverse axial projection (Fig. 6-8A and B).1,4,5

FIGURE 6-8 A, The patient’s arm is placed on the cassette, with the elbow completely flexed. The central beam (pointer) is perpendicular to the cassette. B, The radiograph demonstrates the olecranon, trochlea, and medial epicondyle. Contrast this view with that of Figure 6-7B.

Other views of the elbow also may be used,1,4,5 but those just discussed are usually sufficient. In fact, when questions arise regarding routine AP, lateral, and oblique views, a CT scan with reformatting in the coronal and sagittal planes or an MRI scan is frequently obtained instead of special views.

ASSESSMENT OF RADIOGRAPHS/COMPUTED RADIOGRAPHY IMAGES

The relationship of the radial head to the capitellum should be constant regardless of the view obtained (Fig. 6-9A-C).5,26,28 The radius is normally bowed at the level of the tubercle. Therefore, the line should be drawn in the midpoint of the radial head, not extended to include this portion of the radial shaft.

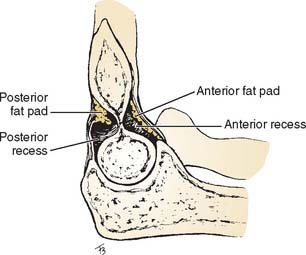

Careful evaluation of the fat pads and supinator fat stripe is essential. These structures are best observed on the lateral (see Fig. 6-2) and radial head (see Fig. 6-6) views. The anterior and posterior fat pads are intracapsular but extrasynovial.5,8,10,26,28 The anterior fat pad is normally visible on the lateral view. The posterior fat pad is obscured owing to its position in the olecranon fossa (Fig. 6-10). Displacement of the fat pads, particularly the posterior fat pad, is indicative of an intra-articular fluid collection due to inflammation or hemarthrosis due to trauma.5,8,10,26,28 Norell26 reportedthat 90% of children with displaced posterior fat pads had elbow fractures. This finding is less specific in adults, but if present in patients following trauma (see Fig. 6-9C), a fracture is likely. Cross-table lateral views may be more specific. A lipohemarthrosis, which is more specific for an intra-articular fracture, may be evident.5,26,28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree