Diagnostic Elbow Arthroscopy and Loose Body Removal

Raymond R. Drabicki

Larry D. Field

Felix H. Savoie III

Despite what was thought a risky procedure, recent advances in elbow arthroscopy have enabled surgeons to treat a broad spectrum of disorders. An improved understanding of neurovascular anatomy, technologic improvements in arthroscopic equipment, and refined surgical procedures have made elbow arthroscopy safer and more effective.

Removal of loose bodies is perhaps the most common and rewarding arthroscopic procedure involving the elbow. Arthroscopic identification and removal of such impediments to joint motion have significant advantages. With careful portal placement, the arthroscope can be used to evaluate all compartments of the elbow. In addition, small portal incisions limit scar formation yet provide an outlet for easy loose body extraction.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History and Physical Examination

A careful history, physical examination, and appropriate imaging are imperative prior to arthroscopic excision of loose bodies and osteophytes within the elbow joint. Frequently, patients with loose bodies present with pain, stiffness, clicking, catching, and locking of the elbow joint. In some cases, these exam findings may present as subtle losses of flexion or extension accompanied with a small effusion, which is palpable in the posterolateral gutter (1).

Preoperative planning for elbow arthroscopy should always include a detailed history for prior elbow surgery, namely, ulnar nerve neurolysis or transposition. Physical examination for ulnar nerve subluxation cannot be overemphasized. A subluxated or dislocated ulnar nerve can be found in 16% of the normal population (1). Awareness of aberrant anatomy is imperative to prevent iatrogenic neural injury.

Imaging

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the elbow should be routinely obtained. Figure 32.1 demonstrates the presence of a loose body in the anterior aspect of the elbow. CT or MRI may be warranted as standard radiographs fail to demonstrate loose bodies in up to 30% of patients (1). Common locations for loose bodies include the coronoid fossa, olecranon fossa, and posterior aspect of the lateral gutter. It is important to note that loose bodies often migrate and may be difficult to see on imaging. In the absence of radiographic evidence of a loose body, high clinical suspicion should dictate arthroscopic inspection for a loose body.

Decision-Making Algorithms and Classification

Loose bodies within the elbow that cause pain, stiffness, or intermittently restrict motion are indications for surgical intervention. However, prior to surgical intervention, it is critical that the treating surgeon ascertain the etiology of these impediments to normal joint motion. Loose bodies may be the result of osteochondritis dissecans,

degenerative arthritis, synovial chondromatosis, and trauma. A careful plan to address the primary, underlying pathology at the time of surgery serves to prevent the future formation of loose bodies (1).

degenerative arthritis, synovial chondromatosis, and trauma. A careful plan to address the primary, underlying pathology at the time of surgery serves to prevent the future formation of loose bodies (1).

FIGURE 32.1. A large loose body can be seen in the anterior compartment of the elbow on this lateral radiograph. |

At times, elbow arthroscopy may be contraindicated due to anatomic variations or prior surgery. Absolute contraindications to elbow arthroscopy include aberrant bony or soft tissue anatomy that precludes the safe portal creation. Other contraindications include ankylosis of the elbow, which precludes joint distension, and local soft tissue infection in the area of portal sites. Prior ulnar nerve transposition is a relative contraindication if it interferes with portal positioning. However, elbow arthroscopy can be utilized if the ulnar nerve is identified with open dissection and protected prior to portal creation.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Nonoperative

Loose bodies in the elbow often present with mechanical symptoms that obstruct normal joint motion and predispose the joint to premature osteoarthritic wear. As a result, the role of conservative treatment is limited to asymptomatic loose bodies.

Operative Indications

Loose bodies in the elbow may restrict the patient’s range of motion and render the joint cartilage prone to injury and arthritic degeneration. Loss of elbow motion, crepitus, pain, intermittent locking, and catching may be present on physical examination. Physical examination consistent with these findings in correlation with radiographic evidence suggestive of loose bodies in the elbow warrants arthroscopic intervention and loose body removal.

TECHNIQUE

Anesthesia

Anesthesia options include general anesthesia and regional blocks. General anesthesia is more commonly used, as it provides greater flexibility with respect to patient positioning and postoperative examination. The prone and lateral decubitus positions are poorly tolerated in an awake patient, and as a result, these positioning methods are most amenable to general anesthesia. General anesthesia also allows the surgeon to perform postoperative neurologic exams.

In patients who are unable to tolerate general anesthesia, interscalene, axillary, and regional intravenous (Bier) blocks can be used. Although these blocks can be used in combination with general anesthesia for postoperative pain management, their usage as the primary means of anesthesia has several disadvantages including limited tourniquet time, incomplete blockade of the surgical site, and pain from tourniquet constriction.

Patient Positioning

Supine

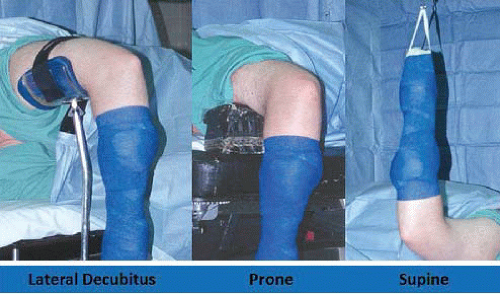

Once the patient is positioned supine on the operating table, the operative extremity is lateralized on the operating table, so that the shoulder is placed at the edge of the bed. The operative extremity is placed in 90° of shoulder abduction, 90° of elbow flexion, and neutral forearm rotation and a nonsterile arm tourniquet is applied (Fig. 32.2). Traction is applied with the use of a traction device.

The supine position offers several advantages to the elbow arthroscopist. The surgeon is easily able to convert to an open procedure if necessary. Lastly, this position enables quick access to the patient’s airway and the choice of multiple effective anesthetic regimens. Disadvantages of the supine position include the necessity of a traction setup and the inability to easily visualize and work in the posterior compartment.

Prone

The prone position was described as an alternative method for positioning. Improved access to the posterior compartment of the elbow was realized, and the need for a traction apparatus was eliminated. Once the patient is intubated on a gurney, he/she are rolled to the prone position on the operating table. The face and chest are padded and supported by a foam airway/head positioner and padded chest rolls. The nonoperative extremity is positioned in 90° of shoulder abduction and neutral rotation with the elbow in 90° of flexion. The elbow and wrist are supported by a padded arm board. On the operative side, an arm board is placed parallel to the operating table centered at the shoulder level. A nonsterile arm tourniquet is applied, and the arm is placed in 90° of shoulder abduction and neutral rotation. The arm is supported at the midhumeral level by a padded bolster attached to the operating table or by a rolled towel bump, which is positioned on top of the arm board, which suspends the elbow in 90° of flexion (Fig. 32.2).

In the prone position, several advantages are realized. The elbow is easily manipulated from flexion to full extension. A traction setup and arm-positioning device are not necessary. The posterior compartment of the elbow is easily accessible. In addition, flexion of the elbow allows the neurovascular structures to sag anteriorly, providing a greater margin of error when establishing anterior portal sites. Lastly, as with the supine position, open procedures are easily performed if necessary. Drawbacks of the prone position primarily relate to patient positioning, ventilation, and anesthetic options. It is imperative to support the head and face with foam padding to secure the airway, and chest rolls are needed to facilitate ventilation. Regional anesthesia is poorly tolerated in most patients, and blocks may not provide adequate anesthesia, thus necessitating conversion to general anesthesia. In such cases, repositioning is necessary to establish an airway.

Lateral Decubitus

The aim of this position was to take advantage of the benefits of both the supine and the prone position while avoiding the major pitfalls inherent to each setup. A bean bag, sand bags, or kidney rests are used to place the patient in the lateral decubitus position. An axillary roll is appropriately placed. The operative extremity is positioned over an arm holder or over a padded bolster with the shoulder internally rotated and flexed to 90°. The elbow is maintained in 90° of flexion (Fig. 32.2).

The elbow is maintained in the prone position, thus affording the advantages of the prone position. Patient positioning is simplified with respect to prone positioning, and airway maintenance is easily monitored with adequate exposure for conversion from regional to general anesthesia. Disadvantages include the need for a padded bolster and the inconvenience of repositioning should the need for an open procedure arise.

Arthroscopic Portals

Establishing arthroscopic portals about the elbow requires a thorough understanding of the underlying neurovascular, bony, and intra-articular anatomy. Surface landmarks and their relation to underlying neurovascular anatomy should be utilized. Ten common portal sites, dictated by bony, neurovascular, and musculotendinous anatomy have been described in the literature. These portal sites can be used in various combinations to address pertinent pathology and surgical goals.

At the outset of any elbow arthroscopy procedure, it is imperative that various landmarks be localized and marked. The ulnar nerve, olecranon, radial head, medial epicondyle, and lateral epicondyle should all be traced with a marking pen. Palpating and outlining the course of the ulnar nerve cannot be overemphasized. An 18G spinal needle is then used to insufflate the elbow joint with approximately 30 cc of sterile saline. This can be accomplished either through a posterior injection into the olecranon fossa or through the lateral soft spot portal site, which is bounded by the radial head, lateral epicondyle, and olecranon (Fig. 32.3). Resistance to further inflow and often slight extension of the elbow seen as fluid is introduced confirms intra-articular injection. Distension of the joint capsule serves to protect the anterior neurovascular structures by displacing them anteriorly, and hence, further away from planned portal sites.

Proximal Anteromedial Portal

The proximal anteromedial has been recommended as the initial portal for elbow arthroscopy in the prone and lateral decubitus positions (2). Creation of this portal is suggested as it provides the best view of intra-articular structures and is less likely than the anterolateral portal to be affected by extravasation (2). The anterior elbow joint structures including the anterior capsule, coronoid process, trochlea, radial head, capitellum, and both the medial and the lateral gutters can be easily visualized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree