Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches to the Boutonniere Deformity

Neal B. Zimmerman

Ryan M. Zimmerman

Rebecca J. Saunders

Michael A. McClinton

IDENTIFICATION OF THE BOUTONNIERE DEFORMITY

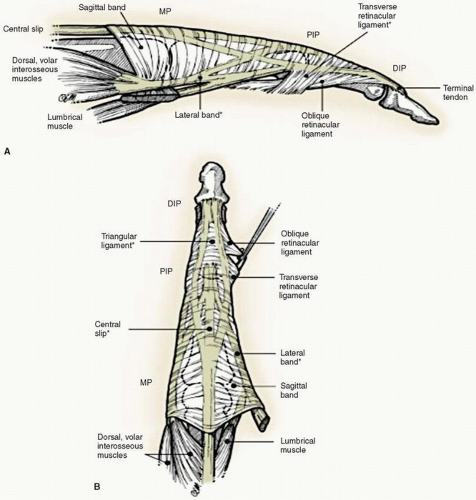

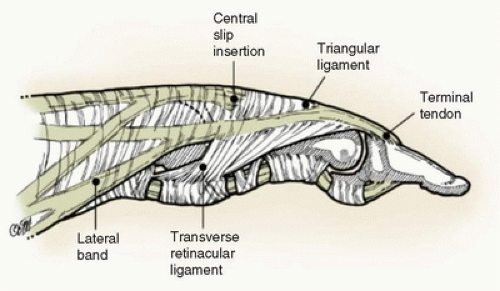

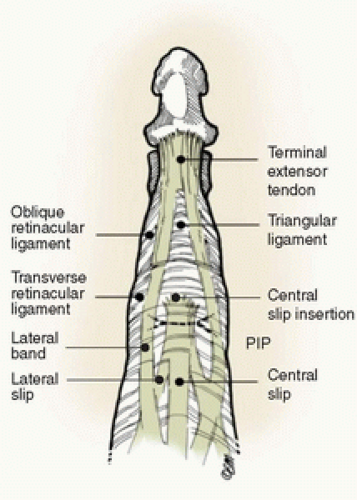

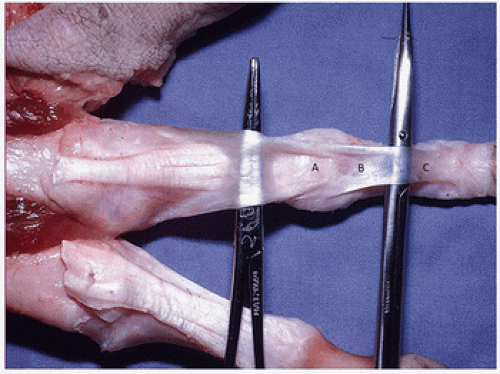

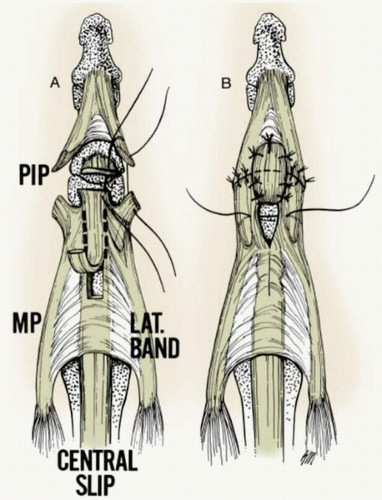

The normal extensor mechanism is composed of an interconnected network of the subdivisions and reinforcing structures of the extensor mechanism surrounding the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. Just proximal to the PIP joint, the extensor mechanism divides into three components. The central slip continues distally to insert into the base of the middle phalanx. The other two limbs diverge from the central slip to insert in the lateral bands, which lie dorsal to the PIP joint center of rotation. The lateral bands are secured in position palmarly by the transverse retinacular ligaments and dorsally by the triangular ligament. Abnormalities of these structures are necessary components of a boutonniere deformity, as will be explained below. The transverse retinacular ligaments run

palmarly from the lateral bands to the volar aspect of the PIP joint and the volar plate. The oblique retinacular ligaments arise from the volar aspect of the PIP joint and flexor sheath to pass dorsally and insert into the terminal tendon as it nears its insertion into the dorsal base of the distal phalanx. They are thought to link extension of the proximal and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Distal to the central slip insertion resides the triangular ligament, a thin translucent sheet that passes over the dorsum of the middle phalanx and functions to tether the lateral bands in their normal dorsal position (Figs. 11-1, 11-2, 11-3 and 11-4).

palmarly from the lateral bands to the volar aspect of the PIP joint and the volar plate. The oblique retinacular ligaments arise from the volar aspect of the PIP joint and flexor sheath to pass dorsally and insert into the terminal tendon as it nears its insertion into the dorsal base of the distal phalanx. They are thought to link extension of the proximal and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Distal to the central slip insertion resides the triangular ligament, a thin translucent sheet that passes over the dorsum of the middle phalanx and functions to tether the lateral bands in their normal dorsal position (Figs. 11-1, 11-2, 11-3 and 11-4).

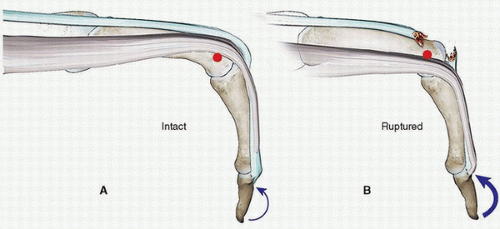

A wide variety of traumatic insults can disrupt the central slip insertion into the base of the middle phalanx. It is important to recognize that injury of the central slip of the extensor mechanism is not synonymous with a boutonniere deformity. Indeed, central slip injury is a necessary

precursor, but alone does not create a boutonniere deformity. Other necessary components to the development of the deformity are palmar migration of the lateral bands and attenuation of the triangular ligament. Following injury of the central slip, if full motion of the digit is continued, as in a neglected or unrecognized injury, proximal migration of the central slip causes reactive overpull through the lateral bands in an attempt to extend the PIP joint. This results in attenuation of the triangular ligament and palmar migration of the lateral bands, which eventually migrate palmar to the axis of PIP joint rotation. Augmented pull through the lateral bands is also responsible for exaggerated extensor tone at the distal joint. As they migrate palmar to the axis of rotation of the PIP joint, the lateral bands reverse their effect and act as flexors rather than extensors of the PIP joint. The summation of these pathologic changes is the development of a boutonniere deformity, which is the subacute to chronic digital deformity of PIP extension lag with DIP hyperextension (Fig. 11-5).

precursor, but alone does not create a boutonniere deformity. Other necessary components to the development of the deformity are palmar migration of the lateral bands and attenuation of the triangular ligament. Following injury of the central slip, if full motion of the digit is continued, as in a neglected or unrecognized injury, proximal migration of the central slip causes reactive overpull through the lateral bands in an attempt to extend the PIP joint. This results in attenuation of the triangular ligament and palmar migration of the lateral bands, which eventually migrate palmar to the axis of PIP joint rotation. Augmented pull through the lateral bands is also responsible for exaggerated extensor tone at the distal joint. As they migrate palmar to the axis of rotation of the PIP joint, the lateral bands reverse their effect and act as flexors rather than extensors of the PIP joint. The summation of these pathologic changes is the development of a boutonniere deformity, which is the subacute to chronic digital deformity of PIP extension lag with DIP hyperextension (Fig. 11-5).

The key to effective treatment of central slip disruption and avoidance of the development of boutonniere deformity is early recognition. Indeed, since the boutonniere deformity progresses from central slip injury to the complex deformity over time, this interlude allows the majority of cases to be treated without surgery. When the central slip is initially disrupted, there is no clinical deformity of the digit. The person is able to make a full fist and to extend the PIP joint, albeit with diminished extensor power, because the lateral bands are intact and still dorsal to the axis of rotation. The most effective way to screen for a central slip disruption is Elson’s test (1,2). We recommend that this maneuver be performed on any patient who presents with a swollen, tender PIP joint following injury. The magnitude of trauma required to disrupt the central slip is highly variable, as is the mechanism of injury. Although boutonniere deformity is classically taught to be an injury involving forced flexion on an extended PIP joint, a different mechanism should not allay concern. An elevated index of suspicion should be held for any injury to the area of the PIP joint. Every finger sprain needs to be evaluated with this specific testing to evaluate the competence of the central slip.

Elson’s test is carried out by flexing the patient’s finger to 90 degrees of flexion at the PIP joint. This is typically done using the edge of the exam table. The person is then asked to attempt forceful PIP extension while the examiner resists the person’s extension effort. In the normal situation, substantial extensor tension is generated at the PIP joint with a very little force generated at the distal joint. This makes sense, because the extensor system is intact, and the lateral bands cannot extend the DIP joint without the central slip also extending the PIP joint, which is being blocked by the examiner. With disruption of the central slip, the opposite occurs. Diminished extensor tone is seen at the PIP joint with prominent or even exaggerated extensor force at the distal joint. This finding is also commonsense, as the disrupted central slip can now retract further than usual, whether or not the PIP joint is blocked, transmitting force

to the terminal tendon through the lateral bands (1,3,4) (Fig. 11-6). The pseudo-boutonniere deformity is caused by a hyperextension injury of the PIPJ resulting in a flexion contracture without injury to the central slip and resultant lateral band migration and tightening. This can lead to stretching of the central slip over time resulting in decreased PIP extension. Unlike the boutonniere deformity, there is no disruption of the extensor mechanism. Testing with Elson’s maneuver will show good extension force at the PIPJ and little force at the DIPJ, as seen in the normal situation (5).

to the terminal tendon through the lateral bands (1,3,4) (Fig. 11-6). The pseudo-boutonniere deformity is caused by a hyperextension injury of the PIPJ resulting in a flexion contracture without injury to the central slip and resultant lateral band migration and tightening. This can lead to stretching of the central slip over time resulting in decreased PIP extension. Unlike the boutonniere deformity, there is no disruption of the extensor mechanism. Testing with Elson’s maneuver will show good extension force at the PIPJ and little force at the DIPJ, as seen in the normal situation (5).

The differential diagnosis of a swollen, painful PIP joint includes central slip disruption, fracture (of either the bony portion of the middle phalanx encompassing the central slip insertion or elsewhere), collateral ligament injury, volar plate damage, capsular sprain, inflammatory or crystalline arthropathy, as well as infection.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Acute central slip injury, the inciting factor in a boutonniere deformity, often presents with no clinical deformity. Disruption of the central slip may not be initially clinically evident and needs to be suspected and tested for.

Examine every injured PIP joint using Elson’s test to determine central slip integrity.

Failure of the central slip leads to diminished extensor power at the PIP joint and increased extensor power at the DIPJ during Elson’s test.

Untreated central slip injuries result in volar migration of the lateral bands, attenuation of the triangular ligament, and development of the boutonniere deformity.

EARLY CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Each case of a suspected central slip injury should be evaluated radiographically, including orthogonal views of the injured digit, in addition to the clinical examination described above. The vast majority of acute and chronic boutonniere deformities can be treated nonsurgically with acceptable results. It is worthwhile to remember that a mild extensor lag at the PIP joint is commonly not a significant impediment to hand function as long as the person is able to make a nearly full fist with good strength. The overarching goal of all treatments for boutonniere deformities is to increase deficient extensor tone at the proximal joint and to decrease exaggerated extensor tone at the distal joint.

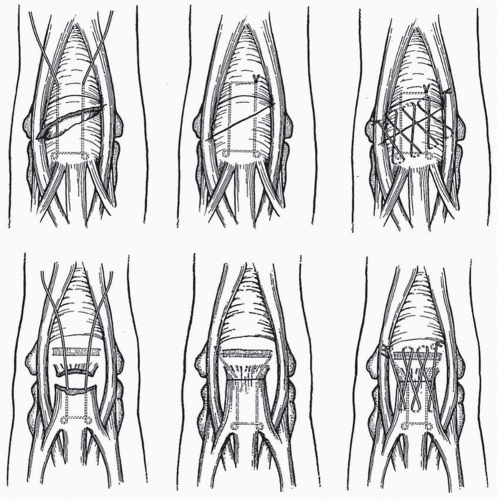

Acute Osseous or Open Injuries

Radiographs may demonstrate an injury to the PIP joint with an osseous fragment, which includes the central slip insertion. In these cases, the osseous fragment with the contiguous central slip is repaired if feasible with fine wires or sutures. If the fragment is very small or insufficient for secure fixation, the central slip can be isolated from the fragment and a bone anchor used to insert it into its normal position at the dorsal base of the middle phalanx. An open injury of the PIP joint with disruption of the central slip necessitates direct repair by any of a variety of direct tendon repair techniques or mobilization of local tissues such as the lateral bands, central slip, or a portion of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon (Figs. 11-7 and 11-8) (6,7,8,9).

Acute Closed Soft-Tissue Injuries and Chronic Boutonniere Deformities With a Supple PIP Joint

If the injury presents acutely or chronically with a fully passively flexible PIP joint, a common protocol is to initiate treatment with a splint holding solely the PIP joint in full extension. The duration of splinting is variable but usually comprises 6 to 8 weeks of full-time splinting, followed by nighttime splinting for another 6 weeks. Coupled with full-time extension of the PIP joint, the patient is asked to actively flex the distal joint. This has the effect of bringing the lateral bands back dorsal to the axis of rotation of the PIP joint, which serves to stretch the transverse retinacular ligaments and preclude them from shortening which would trap the lateral bands volar to the axis of PIP rotation. It also stretches the oblique retinacular ligaments, thus decreasing the tendency for hyperextension of the DIPJ while promoting gliding of the lateral bands (Fig. 11-9).

The early short arc motion (SAM) protocol can also be used in the management of closed supple boutonniere injuries. Evans treated 36 people seen within 3 to 4 weeks of injury. Patients were

initially immobilized in casts for 2 to 3 weeks to reduce edema and improve passive PIP extension. Patients were asked to perform a 30- to 40-degree arc of active PIP flexion in therapy two times per week under direct supervision. The PIP was splinted in full extension at all other times. Patients were seen for 8 weeks, and the average PIP flexion at discharge was 92 degrees with an extension lag of -6 degrees. Average DIP flexion was 47 degrees (10). Utilization of the SAM protocol advocates for an earlier return to function by decreasing the duration of therapy due to the development of excessive stiffness caused by prolonged immobilization.

initially immobilized in casts for 2 to 3 weeks to reduce edema and improve passive PIP extension. Patients were asked to perform a 30- to 40-degree arc of active PIP flexion in therapy two times per week under direct supervision. The PIP was splinted in full extension at all other times. Patients were seen for 8 weeks, and the average PIP flexion at discharge was 92 degrees with an extension lag of -6 degrees. Average DIP flexion was 47 degrees (10). Utilization of the SAM protocol advocates for an earlier return to function by decreasing the duration of therapy due to the development of excessive stiffness caused by prolonged immobilization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree