Abstract

Objective

To develop a classification for neuromuscular disease patients in each of the three motor function domains (D1: standing and transfers; D2: axial and proximal function; D3: distal function).

Materials and methods

A draft classification was developed by a study group and then improved by qualitative validation studies (according to the Delphi method) and quantitative validation studies (content validity, criterion validity and inter-rater reliability). A total of 448 patients with genetic neuromuscular diseases participated in the studies.

Results

On average, it took 6.3 minutes to rate a patient. The inter-rater agreement was good when the classification was based on patient observation or an interview with the patient (Cohen’s kappa = 0.770, 0.690 and 0.642 for NM-Score D1, D2 and D3 domains, respectively). Stronger correlations (according to Spearman’s coefficient) with the respective “gold standard” classifications were found for NM-Score D1 (0.86 vs. the Vignos Scale and −0.88 vs. the Motor Function Measure [MFM]-D1) and NM-Score D2 (−0.7 vs. the Brooke Scale and 0.64 vs. MFM D2) than for NM-Score D3 (0.49 vs. the Brooke scale and −0.49 vs. MFM D3).

Discussion/conclusions

The NM-Score is a reliable, reproducible outcome measure with value in clinical practice and in clinical research for the description of patients and the constitution of uniform patient groups (in terms of motor function).

Résumé

Objectifs

L’objectif de cette étude est le développement d’une classification rapide et reproductible en grades de sévérité pour les patients porteurs d’une maladie neuromusculaire dans chacun des 3 domaines de fonction motrice (D1 : position debout et transferts ; D2 : motricité axiale et proximale ; et D3 : motricité distale).

Patient et méthodes

Plusieurs phases de validation qualitative (méthode Delphi) et quantitative (validité de contenu, concurrente et inter-observateur) ont été nécessaires après la proposition d’une première classification par un groupe d’étude. Respectivement pour chacune des phases, 161 et 229 patients porteurs de maladies neuromusculaires d’origine génétique ont été inclus dans ces 2 phases.

Résultats

La durée moyenne de passation de la classification est de 6,3 minutes (DS : 3,7). La fiabilité inter-observateur est satisfaisante lorsqu’elle est utilisée à partir de l’interrogatoire ou de l’observation du patient en situation écologique (kappa = 0,770, 0,690 et 0,642 pour NM-Score D1, D2 et D3 respectivement). De meilleurs corrélations avec les échelles de références (mesurées par le coefficient de Spearman) sont retrouvées pour le NM-Score D1 (vs Vignos = 0,86, vs MFM D1 = −0,88) et D2 (vs Brooke = −0,7, vs MFM D2 = 0,64) que pour le NM-Score D3 (vs Brooke = 0,49, vs MFM D3 = −0,49).

Discussion/conclusions

La classification NM-Score est une classification fiable et reproductible, pouvant être utilisée dans la pratique clinique courante pour le suivi des patients ainsi qu’en recherche clinique pour la description des populations et la constitution de groupe d’atteinte fonctionnelle identique.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Over the last few decades, progress in research and clinical care has increased the life expectancy of patients with neuromuscular diseases (NMDs). Assessment of NMDs has become commonplace during clinical follow-up and as an outcome measure in much-awaited clinical trials. A rigorous, appropriate metrological approach is essential when developing an assessment tool. It is no longer possible to make do with approximate measures or to use tools that are not appropriate for progressive diseases.

Loss of muscle strength is a symptom of all NMDs. Depending on the disease in question, this loss of strength affects different muscles to different extents. In clinical trials, the therapeutic target is primarily the muscle fibre; it is important to consider not only changes in bodily functions such as strength (i.e. mechanical aspects) but also the latter’s functional relevance (i.e. the impact on mobility and activities of daily living) . Motor function assessment (i.e. measurement of the impact of the NMD on functional limitations) is well accepted by patient and therapists alike .

For the most commonly used motor function scales, assessment of a patient takes about 30 minutes and presupposes that the therapist has been specifically trained in this procedure. However, precise evaluation of motor function is not necessary in routine clinical practice (or in some research projects). For example, estimation of levels or grades of functional severity may be enough for the constitution of patient groups that are homogeneous in terms of motor function. In the field of NMD, a number of functional scores have been published. However, these scores either do not take account of the various domains of motor function (such as standing and transfers, axial/proximal motor function and the distal motor function) or are not sufficiently specific for the population being studied.

For example, the Brooke Upper Extremity Scale and the Vignos Lower Extremity Scale are specifically used to grade patients suffering from muscular dystrophy but focus solely on arm function and gait, respectively. Moreover, literature data on the validation of these two tools are scarce.

On the basis of the research developed by Palisano et al. in the field of cerebral palsy, we have developed a classification (called the “NM-Score”) to rate the severity of motor function impairment in each of the three domains of motor function (D1: standing and transfers; D2: axial and proximal motor function; D3: distal motor function), as previously described for the development and validation of the Motor Function Measure (MFM) by Bérard et al. . We sought to create a simple, quick-to-use tool whose primary goal is to classify patients by providing a general representation of their functional status in their usual environment via the written description of each severity grade in each domain of motor function.

Development of the NM-Score comprised the following steps:

- •

generation of an initial classification by a working group;

- •

content validation (according to the Delphi process);

- •

validation of the inter-rater agreement;

- •

criterion validation.

The classification was modified at each step, in order to obtain the final version presented here.

1.2

Materials and methods

Fig. 1 presents the different steps in the development of the NM-Score and shows the timeline, the methodology and the numbers of patients and professionals involved in each step. The study protocol was submitted to the local independent ethics committee (CCP Lyon Sud Est 2, Lyon, France) but was considered not to be subject to the French legislation on biomedical research. Nevertheless, the investigator handed an information sheet to the patient prior to inclusion in the study.

1.2.1

Generation of an initial version of the NM-Score

We performed an exhaustive review of the literature on motor function assessment tools in the field of NMD. Eight experts in the treatment of NMDs (three physiotherapists, an occupational therapist and four physicians) developed the first version of the NM-Score (referred to as “NM-Score VP1”) in four meetings between March 2008 and February 2009. In their normal practice, four of the experts worked in the paediatric area and the other four worked with adults. The experts’ mean time since qualification was 13.7 years (range: 2–25).

The different severity grades in the NM-Score VP1 classification were defined for each of the three motor function domains (D1: standing position and transfers; D2: axial and proximal motor function; D3: distal motor function) on the basis of the experts’ clinical experience, the literature review and an analysis of data from the MFM’s validation study of 303 NMD patients . A pilot study was performed on 48 NMD patients, in order to help define each level of the rating scale.

For each of the three motor function domains, the experts suggested a five-grade classification (Grade 0: no impairment; Grade 1: slight impairment; Grade 2: moderate impairment; Grade 3: severe impairment; Grade 4: very severe impairment). Several so-called major criteria were used primarily to distinguish between two grades: the patient’s usual ability to walk, run and jump (for D1), his/her usual ability to sit upright, perform activities involving proximal motor actions and hold his/her head up (for D2) and his/her usual ability to handle objects (for D3). Several minor criteria (with less discriminant power) were used to improve the description of each major criterion. These minor criteria (identified during the patient study) concerned the need for technical aids and/or human assistance. A minor criterion was selected for use in improving the description of a grade when it was met by at least 80% of the patients in the corresponding grade.

1.2.2

Content validation

In order to analyze the NM-Score VP1’s content validity, a Delphi-type consensus process was applied. This step enabled us to gather opinions and comments on the relevance of the classification’s content (and, in particular, the selected major and minor criteria) from several French-speaking experts in the field of NMD.

The Delphi process is an iterative, interactive procedure with two to four rounds. The selected experts were representative of their profession, had power to implement the findings and were not likely to be challenged as experts in the field (as suggested by Fink et al. ). After each round, the expert group is informed of the results, which are then used to build the questionnaire for the next round. The process ends when the group reaches a predefined level of agreement or when the exchanged information has enabled the process’s objectives to be met.

Thirty-six French-speaking physiotherapists, occupational therapists and physicians (based in France, Belgium and Switzerland) with acknowledged expertise in NMD and who had not participated in the first phase of the study were invited to participate, and 29 accepted (9 physiotherapists, 3 occupational therapists and 17 physicians). Ten participants worked exclusively with adults, 14 worked exclusively with children and five worked with both adults and children. The experts’ mean time since qualification was 11.8 years (range: 3–28).

In the first round in the Delphi process, a questionnaire and the NM-Score VP1 classification were e-mailed to the participating experts. The questionnaire was divided into four sections and included a total of 28 items. Each item also featured an open-ended question, so that the experts were encouraged to explain their answers. The first part (part A) was composed of four questions on the need for a new classification system. Parts B, C and D were respectively dedicated to the D1, D2, and D3 domains and included 24 questions on the definition and description of each grade and the inter-grade differences. Each item was scored on a nine-point Likert scale (with 1 indicating “strongly disagree”, 5 indicating “neither agree nor disagree” and 9 indicating “strongly agree”). Consensus for a given item was reached when there was either a high degree of agreement or no disagreement. Agreement was defined as a median agreement score of > 7, with at least 80% of the experts giving a score of > 7. Disagreement was defined as more than 30% of the individual scores falling in the ranges 1 to 3 and 6 to 9.

In the second round, the questionnaire included 17 items; the 11 items from the first questionnaire that had not obtained a consensus in the first round and 6 items concerning the classification’s ease of use and administration conditions. The experts were invited to use the NM-Score VP1 classification in their daily practice before completing the questionnaire.

1.2.3

Inter-rater reliability

This validation phase assessed the degree of agreement between scores reported by different therapists, i.e. the inter-rater reliability. Based on the explanations given by examiners in cases of disagreement, this phase was also intended to help us improve the classification and develop a new version (referred to as “NM-Score VF1”).

For each patient who met the inclusion criteria, two examiners (physicians, physiotherapists or occupational therapists) had to independently rate the patient according to the NM-Score on the basis of:

- •

an interview with the patient or their family;

- •

observation in an ecological context and/or;

- •

the patient’s medical records.

A given pair of examiners was only allowed to grade five patients at most. If the examiners disagreed over the rating, they had to explain the reasons for their disagreement.

Six clinics and reference centres for NMDs (located in France and French-speaking Belgium) participated in the inter-rater reliability study. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: a patient with confirmed NMD, aged between 6 and 60, known to the two examiners for less than three months and having consulted in the three months preceding the rating visit. The 23 therapists having agreed to participate in the validation study (seven physiotherapists, six occupational therapists and 10 physicians) had to familiarize themselves with the NM-Score before rating any patients.

1.2.4

Criterion (concurrent) validity

The objective of this part of the study was to achieve criterion validation for the NM-Score against three so-called “fuzzy” reference scales (given the imperfect nature of the “gold standards” in this field): the MFM, the Brooke scale and the Vignos scale. In order to standardize these evaluations, all the therapists participating in this part of the study had already been trained in administration of the MFM. Furthermore, the criteria for the Brooke and Vignos classifications were explained on the case report form.

Fourteen clinics and NMD reference centres participated in the criterion validity study. The included patients had to be aged between 6 and 60 and have a confirmed NMD. All the therapists participating in the criterion validation study had to familiarize themselves with the NM-Score before starting the assessment (by carefully reading the rating instructions and looking at the classification as a whole).

The therapists rated the patients according to the NM-Score on the day of the MFM assessment (but before the latter was administered).

1.2.5

Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables were described as the mean, standard deviation (SD), range and quartiles. Qualitative variables were described as the number and percentage.

The inter-rater agreement was analyzed for each field (D1, D2 and D3) and each rating condition (medical records, an interview and/or an observation in an ecological context) by using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ), which indicates whether the agreement is better than that expected by chance. Depending on the value of κ, the degree of agreement can be interpreted as fair (< 0.4), moderate (0.4 to 0.59), substantial (0.6 to 0.8) and almost perfect (> 0.8) .

In order to analyze the NM-Score’s criterion validity, we chose “fuzzy” gold standard scales for each domain (D1, D2 and D3). We assessed the degree of agreement between the NM-Score (in five ranked classes and for each of the D1, D2 and D3 domains) and the value of the MFM (a quantitative score ranging from 0 to 100). The degree of agreement between the NM-Score severity grade and the Vignos and Brooke scores was also studied. We calculated various measures of agreement, such as Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Development of the initial classification and a qualitative, Delphi-like analysis of the content validity

In the first round of the Delphi process, a consensus was reached for 17 of the 28 items in NM-Score VP1. All the experts agreed on the necessity of a new classification system for patients suffering from NMD based on their performance of activities of daily living. Twenty-two of the 28 experts thought that the classification had potential applications in both routine clinical practice and clinical research. All the experts considered that one of the major strengths of the NM-Score was its reliance on a description of the patient’s performance in all motor function domains (rather than walking ability alone).

After the first round of the Delphi process, the classification was revised using the experts’ comments and was sent back with a questionnaire for a second round. A consensus was reached for 16 of the 17 items. The only non-consensual point concerned the age from which the classification could be administered; 13 of the 28 experts thought that the classification could not be correctly applied to children as young as four. In the second round of the Delphi process, the VP2 classification was used by the experts to rate a total of 161 patients. The largest number of patients rated by any one expert was 24 and all the experts agreed that the classification was easy to use.

1.3.2

Quantitative analyses

1.3.2.1

The inter-rater reliability study

Seventy-one patients (47 males and 24 females, aged between 6 and 50) were included in this study of inter-rater reliability. The mean ± SD age was 18.7 ± 13. Sixty-six percent were aged under 18 on the day of the evaluation.

For 36 of the 71 patients, the two evaluations were performed on the same day. In 76% of cases, the time interval between the two evaluations was less than two weeks (the longest interval being 3 months). In terms of the rating conditions, 32 evaluations were based solely on observation of the patient, 20 were based solely on medical records and 9 were based solely on an interview with the patient and/or the patient’s family. The other evaluations involved two or more of these situations. The κ coefficients [95% confidence interval (CI)] for D1, D2 and D3 were respectively 0.72 [0.57 to 0.83], 0.62 [0.47 to 0.75] and 0.56 [0.39 to 0.71] ( Table 1 ). For D1, D2 and D3, the percentages of inter-rater agreement were respectively 82.9%, 78.1% and 75.6% and the κ coefficients [95% CI] were respectively 0.77 [0.59 to 0.90], 0.69 [0.48 to 0.85] and 0.64 [0.43 to 0.82]. These values were higher when evaluations were based on patient observation and/or a patient interview.

| Overall study population ( n = 71) | Patients graded on the basis of an observation and/or an interview ( n = 41) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | % agreement | κ (95% CI) a | % agreement | κ (95% CI) a |

| D1 | 78.87 | 0.72 (0.57–0.83) | 82.93 | 0.77 (0.59–0.90) |

| D2 | 71.83 | 0.62 (0.47–0.75) | 78.05 | 0.69 (0.48–0.85) |

| D3 | 70.42 | 0.56 (0.39–0.71) | 75.61 | 0.64 (0.43–0.82) |

a The confidence interval (CI) was calculated using the Bootstrap method.

Nineteen cases of disagreement were analyzed. In 15 cases, at least one therapist had not correctly read the introduction or the instructions for use. In particular, the therapist at fault did not apply the major criteria before referring to the minor criteria when rating the patient.

1.3.2.2

The criterion validity study

A total of 158 patients were included in this validation phase. The great majority of these patient were able to walk ( n = 124). There were more males ( n = 102) than females in the study population; this was due to the presence of a large number of patients suffering from the male-only diseases Duchenne muscular dystrophy ( n = 27) and Becker muscular dystrophy ( n = 10). The other diagnoses were myopathy and congenital muscular dystrophy ( n = 26), infantile spinal muscular atrophy ( n = 22), peripheral neuropathies ( n = 21), myotonic dystrophy type 1 ( n = 17), facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy ( n = 12), girdle myopathies ( n = 8) and other NMDs (15). The mean ± SD time needed to administer the NM-Score was 6.3 ± 3.7 minutes per patient ( n = 158). In order to study the classification’s criterion validity, 148, 143 and 158 patients were scored against the Vignos, Brooke and MFM scales, respectively.

The distribution of the Vignos scores for each NM-Score D1 grade and the distribution of the Brooke scores for each NM-Score D2 and D3 grade are shown in Table 2 . The distribution between the various grades was relatively balanced for D1 and D2 but was less balanced for D3 (for which there were relatively few grade 4 patients). Since the dispersion of the Vignos score was low for grades 0 and 4 in NM-Score D1, a floor effect and a ceiling effect can be suspected for at least one of the two scales. However, the small sample size (8 patients) for grade 0 in NM-Score D1 makes it difficult to confirm the presence of a floor effect. The means Vignos score increased steadily from NM-Score D1 grade 0 to grade 4. Only grade 3 was associated with high dispersion of the Vignos score (mean: 5.75; range: 2–9), suggesting that the level of impairment in grade 3 patients was heterogeneous. For NM-Score D2 and D3, the dispersion of the Brooke score was high and was essentially the same when comparing grades 0 and 1 in each domain (NM-Score D2 grade 0 [1–3] and grade 1 [1–5]; NM-Score D3 grade 0 [1–3] and grade 1 [1–4]). For the other grades, the mean values and distributions of the Brooke score increased steadily from grade 2 to grade 4 in the NM-Score D2 and D3 domains.

| NM-Score D1 | Number of patients | Vignos score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | p25 | p50 | p75 | Maximum | ||

| 0 | 8 | 1 (0) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 57 | 1.6 (0.7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 38 | 2.76 (1.3) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 3 | 16 | 5.75 (2.24) | 2 | 3.5 | 6.5 | 7 | 9 |

| 4 | 29 | 8.93 (0.26) | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Total | 158 | 3.75 (3.05) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6.5 | 9 |

| NM-Score D2 | Number of patients | Brooke score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | p25 | p50 | p75 | Maximum | ||

| 0 | 44 | 1.2 (0.51) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 65 | 1.6 (0.8) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 2 | 17 | 2.65 (1.0) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 11 | 3.9 (1.0) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | 6 | 5.2 (0.4) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Total | 143 | 1.9 (1.3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| NM-Score D3 | Number of patients | Brooke score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Minimum | p25 | p50 | p75 | Maximum | ||

| 0 | 42 | 1.4 (0.7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 52 | 1.4 (0.7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 2 | 50 | 2.6 (1.3) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3.5 | 5 |

| 3 | 7 | 4.1 (1.2) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | 2 | 5.5 (0.7) | 5 | 5 | 5.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 143 | 1.9 (1.3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

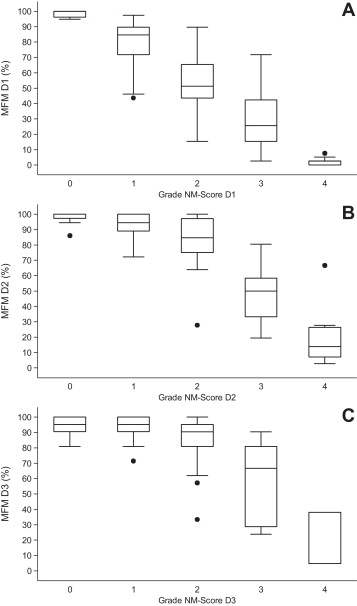

The distributions of the D1, D2 and D3 MFM scores by NM-Score D1, D2 and D3 grade are presented as box plots in Fig. 2 . For the NM D2 score and (above all) the D3 score (but not the NM-Score D1 score), there were no significant differences between grades 0 and 1 in terms of the mean Brooke score or mean MFM score. The dispersion of the MFM D3 score for the NM-Score D3 grades 3 and 4 was high, although the sample sizes were small (7 and 3 patients, respectively); this must be taken into account when interpreting the box plots. Moreover, for grade 4, the first quartile and the median were equivalent; this is not visible on the box plots.

The criterion validity for each NM-Score domain with respect to the reference scales was estimated by calculating Spearman’s coefficient and its 95% CI ( Table 3 ). The best correlations were observed for NM-Score D1 and NM-Score D2, which were more strongly correlated with the MFM score than with the functional scores.

| Reference scale | Spearman’s coefficient | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vignos vs. NM-Score D1 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| MFM D1 vs. NM-Score D1 | −0.88 | −0.91 | −0.83 |

| Brooke vs. NM-Score D2 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.73 |

| MFM D2 vs. NM-Score D2 | −0.70 | −0.77 | −0.60 |

| Brooke vs. NM-Score D3 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.61 |

| MFM D3 vs. NM-Score D3 | −0.49 | −0.60 | −0.36 |

1.4

Discussion

The NM-Score is a valid, reliable tool for classifying patients into five categories as a function of the degree of functional impairment in the three domains of motor function (D1: standing and transfers; D2: axial and proximal function; D3: distal function: D1).

This new classification has been welcomed by the many practitioners and researchers who have already used it. The French version of the NM-Score can be downloaded free of charge from the MFM website ( http://www.mfm-nmd.org/accueil.aspx ).

The NM-Score is a simple, quick-to-administer tool for describing a patient’s motor functions. Detailed training is not required for use of the NM-Score; users are simply told to read the introduction and instructions carefully and to get to know the tool by doing a few trial ratings. We consider that this classification facilitates discussion between the physician and the patient by focusing on activities of daily living and by identifying factors that aggravate or facilitate motor function in an ecological context. This classification also enables healthcare professionals to use a common vocabulary when they talk about their patients. It notably takes account of the patient’s opinions and those of his/her family, since the interview probes these aspects.

The NM-Score describes the patient in terms of a severity grade that is not restricted to his/her ability to walk. In fact, the NM-Score is based on a clinical description of motor function, which yields a comprehensive view of the patient’s functions in all domains. This classification can be likened to the multicriterion TNM tumour staging classification. Depending on the patient’s disease and/or age, a specific pattern may be observed. For example, the NM-Score’s D1 and D2 domains are most affected (regardless of the patient’s age) by infantile spinal muscular atrophy or facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, where the impairment is primarily proximal in nature. In Duchenne muscular dystrophy, changes in NM-Score D1 during early-stage disease are followed by changes in NM-Score D2 and then in NM-Score D3.

During the Delphi process, the experts all agreed that there is a need for a classification system based on the patient’s functional limitations in activities of daily living (rather than on their abilities in clinical tests). Most of the experts considered that our classification was useful for clinical research (in the constitution of groups of patients with a similar level of motor function) and clinical follow-up. Two rounds of the Delphi process were needed to obtain a consensus on all the descriptions suggested for each grade. About 30% of the experts thought that the NM-Score could not be used with sufficient accuracy in children under the age of six. In order to avoid difficulties related to the variability of normal psychomotor development in the child, we suggest that the NM-Score can be applied from the age of 6 onwards.

The NM-Score’s inter-rater reliability was good when the tool was administered as part of an interview and/or during observation of the patient in an ecological context. This condition is required for sufficient reliability (Cohen’s κ > 0.60) in all three domains (with κ values of 0.77, 0.69 and 0.64 for D1, D2, and D3, respectively) and enables the use of the NM-Score in multicentre therapeutic trials. By way of a comparison, Palisano et al. studied the Gross Motor Function Classification System and reported a κ of 0.75 in children aged 2 and over, whereas Finkel et al. reported a weighted κ of 0.61 [95% CI: 0.59 to 0.63] for the Test of Infant Motor Performance. Comparisons with other tools are complicated by the fact that ICCs were used to estimate inter-rater reliability. For instance, the ICC for the Brooke score is between 0.96 and 0.99 . By definition, Cohen’s κ is well suited to ordinal variables, such as those in the Brooke, Vignos and NM-Score classifications. The ICC is considered as the most suitable for quantitative variables and is also more dependent on the sample’s variability than Cohen’s κ is; the greater the variability, the closer the ICC is to 1. Hence, with the same parameters, Cohen’s κ will give a lower value than the ICC. Our analysis of inter-rater disagreements during the reliability study showed that in most cases, at least one of the two raters had not complied with initial use of the major criteria when rating the patient. Thus, in the final version of the classification, we moved the minor criteria to a separate page so that they were only used when the rater hesitated between two grades (established using the major criteria).

In terms of criterion validity, NM-Score D1 was very strongly correlated (Spearman’s coefficient: 0.86) with the Vignos score. The low dispersion of the Vignos scores for grade 4 prompted us to suspect a small floor effect.

The Brooke classification measures proximal motor function (grades 1, 2 and 3) and/or distal motor function (grade 3, 4, 5 and 6) of the upper extremities. In fact, the Brooke classification was more strongly correlated with NM-Score D2 (Spearman’s coefficient: 0.64) than NM-Score D3 (Spearman coefficient: 0.49) but both values were lower than for D1. Given that the statistical significance and the breadth of the coefficient’s 95% CI are strongly linked to the sample size, interpretation of these finding is complicated by the fact that there were few patients with a severe impairment in D2 or D3.

The correlation between the MFM and the NM-Score was substantial for D1 and D2 and moderate for D3. Generally, in NMD, the D3 motor function domain is the last to be impaired (except in purely distal NMDs); this is borne out by the patients’ distribution by domain and by grade in the NM-Score and probably limits our ability to interpret the results. In terms of the results, the NM-score’s ability to discriminate between grades 0 and 1 in the D2 and D3 domains appears to be too low, even though we wanted to ensure that grade 0 (corresponding to normal abilities) could be differentiated from even slight impairment (grade 1), such as that due to fatigability in the sitting position during the day or a lack of precision in a certain movement mentioned in the patient interview.

Translation of the NM-Score into English would enable the international dissemination of this new tool.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients and family members who (as always) participated in the project with great enthusiasm. We also thank all the physicians and therapists in the NM-Score working group for enabling the successful conclusion of this project. We thank the Lyon Public Hospitals Group (Hospices Civils de Lyon) for financial and logistic support as part of the Projet Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Inter-Régional 2008 programme.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Au cours des dernières décennies, les progrès de la recherche et de la prise en charge des patients atteints d’une maladie neuromusculaire (MNM) ont permis une augmentation de l’espérance de vie de ces patients. L’évaluation s’est ainsi imposée lors du suivi clinique des patients, et dans le domaine de la recherche clinique pour répondre aux premiers essais cliniques tant attendus. Une métrologie rigoureuse et adaptée est indispensable lors du développement d’outil d’évaluation. Il n’est pas possible de se contenter d’une quantification approximative ou d’utiliser des outils non adaptés à des pathologies évolutives.

Le symptôme commun à l’ensemble des MNM est la diminution de la force musculaire. Cette diminution de force peut toucher, selon la pathologie, différents muscles à des degrés variables. La cible thérapeutique dans les essais cliniques est de ce fait prioritairement la fibre musculaire et il est important de considérer, en particulier dans les essais thérapeutiques, les altérations des fonctions organiques comme la force (aspects mécaniques) avec leurs pertinences fonctionnelles, c’est-à-dire leurs impacts sur le mouvement et les retentissements de la faiblesse musculaire dans la vie quotidienne . L’évaluation fonctionnelle motrice, qui mesure le retentissement de la maladie neuromusculaire sur les limitations fonctionnelles, est bien acceptée par le patient et les thérapeutes .

Proposer la passation d’une échelle évaluant la fonction motrice à un patient suppose la disponibilité d’un thérapeute formé à sa passation et un temps de passation d’environ une demi-heure quelle que soit l’échelle utilisée. Or, en pratique clinique courante ainsi que dans certains projets d’étude, une évaluation précise de la fonction motrice n’est pas nécessaire. Par exemple, pour la constitution de groupes de patients homogènes en termes de fonction motrice, une appréciation en niveaux ou grades de sévérité de l’atteinte fonctionnelle peut être suffisante. Dans le domaine des MNM, des scores fonctionnels existent déjà dans la littérature. Cependant, ces scores ne prennent pas en compte les différentes composantes de la fonction motrice (comme la position debout et les transferts, la motricité axiale/proximale et la motricité distale) ou ne sont pas suffisamment adaptés à la population étudiée. Par exemple, les scores de Brooke et de Vignos , qui sont spécifiquement utilisés chez les patients atteints de dystrophie musculaire, ne s’intéressent qu’à la fonction des membres supérieurs pour le premier, et à la déambulation pour le second. De plus, peu de données sont disponibles dans la littérature concernant la validation de ces deux outils.

En s’inspirant des travaux de Palisano et al. dans le domaine de la paralysie cérébrale, nous proposons de développer une classification en grades de sévérité d’atteinte fonctionnelle motrice, appelée NM-Score, pour chacun des 3 domaines de fonction motrice (D1 : position debout et transferts ; D2 : motricité axiale et proximale ; et D3 : motricité distale), précédemment décrit lors du développement et la validation de la Mesure de Fonction Motrice par Bérard et al. . Nous souhaitons créer un outil simple et rapide à utiliser dont l’objectif principal est de classer les patients par analogie entre leur état fonctionnel dans leur environnement et la description clinique littérale correspondant à chaque grade de sévérité.

Les différentes étapes du développement de la classification NM-Score comprennent :

- •

la proposition d’une première classification par un groupe d’étude ;

- •

une étude de sa validité de contenu par une méthode Delphi ;

- •

une étude de validation inter-observateur ;

- •

une étude de validation contre critère.

À chaque étape, la classification est modifiée pour aboutir à la version finale présentée dans cet article.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

La Fig. 1 reprend les différentes étapes du développement de la classification NM-Score avec, pour chacune, un calendrier précis, la méthodologie utilisée et le nombre de patients et de professionnels impliqués. Cette étude, soumise au CCP Lyon Sud Est 2, a été considérée en dehors du champ d’application de la loi de bioéthique française. Une note d’information a été remise à chaque patient par leur thérapeute avant leur inclusion.