Design of the Trauma Resuscitation Area

William Scott Hoff

The resuscitative phase of trauma is the specific period of time when events that have transpired during the prehospital phase are linked to the care which will be provided in the hospital. Clinically, this phase represents a time when a rapid primary survey is performed to exclude immediately life-threatening injuries and a coordinated effort is initiated to maintain or restore normal perfusion.1 Subsequently, an organized physical assessment is performed to catalog injuries and prioritize treatment. Successful resuscitation is time dependent. As such, a systematic, organized approach to evaluation and resuscitation is of vital importance in the resuscitative phase of care.

This chapter will outline the necessary elements to optimize trauma resuscitation with regard to physical plant and equipment. Important ergonomic considerations in the design of a trauma resuscitation area will be emphasized.2 A limited list of medications required in the acute phase of trauma care will be reviewed. Finally, large-scale natural disasters and threats of terrorist-initiated catastrophes are pervasive considerations in modern emergency medicine (EM). Accordingly, there are important elements of design that must be considered for the contemporary trauma resuscitation area.

PHYSICAL SPACE—THE TRAUMA RESUSCITATION AREA

All emergency departments (EDs) should be prepared in some capacity to receive injured patients. In general, the national or state-based designation/accreditation standards for trauma centers require some dedicated space in the ED for receiving trauma patients. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma classifies trauma centers as follows:

Level I: An in-house trauma team is available 24 hours a day. The facility can provide full resuscitation and definitive surgical care for all injured patients. Level I trauma centers are typically located in population-dense regions. In addition to providing the highest level of clinical care, these centers have a commitment to training, research, and community outreach.

Level II: The level of clinical care available is very similar to that available at a Level I trauma center. An in-house trauma surgeon is not required, but must be immediately available. Level II centers usually provide trauma care in regions where the population is less dense (e.g., suburban, rural).

Level III: These centers are often the initial contact for injured patients in rural areas. An in-house general surgeon is not required, but must be available in a timely manner. In addition, higher-level subspecialists (e.g., neurosurgeons) are not required. Formalized transfer agreements with Level I/II trauma centers are central to providing optimum patient care in this environment.

Level IV: Physicians skilled in trauma management at the advanced trauma life support (ATLS)-level are available to begin resuscitation and evaluation of injured patients. Surgical resources may be limited and are not mandatory. Level IV trauma centers are designed to stabilize injured patients in remote areas; most patients will require transfer.

For trauma centers and EDs that receive a significant volume of trauma patients or where the luxury of prehospital notification is not existent, a dedicated space

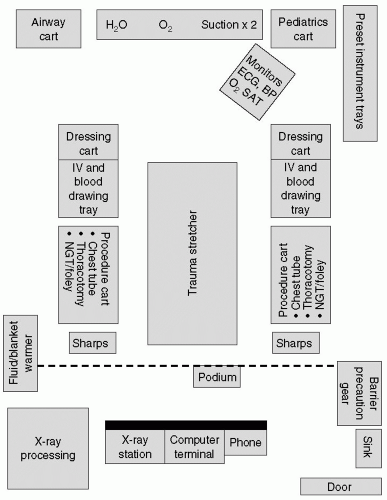

for trauma resuscitation is recommended. The size of the trauma resuscitation area largely depends on the volume and acuity of trauma managed by the institution. Figure 1 illustrates a potential layout for a dedicated trauma resuscitation area, including equipment, specialty carts and clerical components (see the following text). At the very least, the space must comfortably accommodate the full trauma team, necessary equipment, and allow for the performance of the following emergency procedures:

for trauma resuscitation is recommended. The size of the trauma resuscitation area largely depends on the volume and acuity of trauma managed by the institution. Figure 1 illustrates a potential layout for a dedicated trauma resuscitation area, including equipment, specialty carts and clerical components (see the following text). At the very least, the space must comfortably accommodate the full trauma team, necessary equipment, and allow for the performance of the following emergency procedures:

Figure 1 Trauma resuscitation area ECG, electrocardiogram; BP, blood pressure; SAT, oxygen saturation; NGT, nasogastric tube. |

Endotracheal intubation

Cricothyroidotomy/surgical airway

Insertion of central venous catheters

Thoracostomy

Placement of urinary catheters

Resuscitative thoracotomy

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL)

Splinting of fractures

Whenever possible, the trauma resuscitation area should be adjacent but physically separate from the general ED. Distinct entrances and exits for the trauma patient from the remainder of the ED are considered ideal. Maintaining separate access and a dedicated area facilitates security and minimizes disruption to the main ED while focusing the trauma team to trauma resuscitation and care only. Access to nonmedical and any nonessential personnel should be limited. At the same time, convenient access to the radiology suite, operating room, and intensive care unit should be considered. If possible, a radiologic suite with access to plain radiography and computed tomography should be contiguous to or located within the ED.

Preventing hypothermia, an important component of the resuscitative phase, is facilitated by independent temperature control and radiant heaters in the trauma resuscitation area. Sufficient room lighting and an overhead operating room light for each trauma stretcher are imperative and fixtures should not impede movement around the patient. To permit unimpeded circumferential access to the patient, monitoring equipment, suction, and gases should be mounted above the patient on fixed columns or movable overhead booms; the floors should be free of fixed hardware to avoid tripping! The ceiling mounts should be higher than the height of tall members.

LEVEL OF RESPONSE

Regardless of the type of institution (i.e., designated trauma center, community hospital, etc.), a preestablished response to injured patients is essential for organized care of injured patients. In designated trauma centers,

trauma teams consisting of attending physicians, residents, nurses and ancillary personnel routinely respond. In nondesignated hospitals, where a full trauma team is not available, an established procedure (e.g., personnel, tasks) will facilitate the resuscitation/evaluation process. Many institutions have established levels of response to efficiently mobilize personnel. Response levels are determined ideally by field triage criteria or following initial evaluation by an emergency physician:

trauma teams consisting of attending physicians, residents, nurses and ancillary personnel routinely respond. In nondesignated hospitals, where a full trauma team is not available, an established procedure (e.g., personnel, tasks) will facilitate the resuscitation/evaluation process. Many institutions have established levels of response to efficiently mobilize personnel. Response levels are determined ideally by field triage criteria or following initial evaluation by an emergency physician:

Full Response (“Level One Response,” “Trauma Code,” etc.): A level designed for patients who are physiologically unstable or who present with life- or limb-threatening injuries. Full response generally mobilized higher-level personnel (e.g., anesthesiologist, trauma surgeon) to the ED.

Modified Response (“Level Two Response,” “Trauma Alert,” etc.): This level is intended for patients with normal prehospital physiology, but with potentially serious injury based on mechanism of injury. In some institutions, EM physicians are the primary physicians for this level of response.

Trauma Consult: These patients have typically sustained a “low-energy” mechanism of injury and present with normal physiologic parameters. Their evaluation is usually completed by the emergency physician with no formalized team mobilization required. After the initial workup is complete, a referral is made to the trauma surgeon or the appropriate surgical subspecialist for further evaluation.

UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS

Exposure to various bodily fluids, which are potential sources of transmissible disease, is both highly likely and nonpredictable. Therefore, barrier precautions should be mandatory for all health care providers during the resuscitation/evaluation of an injured patient. Barrier precautions include (i) gown, (ii) cap, (iii) nonsterile gloves, (iv) surgical mask, (v) protective eyewear, and (vi) shoe covers.3 These items are ideally located in a designated, fully visible area adjacent to the trauma resuscitation area. In this way, all providers may easily locate and wear protective gear before entering the trauma workspace.

EQUIPMENT

Resuscitation stretchers should be located in the central portion of the resuscitation space. The number of stretchers is dependent on trauma room, size, and the potential for arrival of multiple patients at a single time or frequent arrival of patients (without prenotification). A modicum of equipment, sufficient to temporarily begin trauma resuscitation for all clinical situations and transfer, should be stored under the stretcher:

Patient gowns

Blankets

Small oxygen tank

Nasogastric/orogastric tubes

Urinary catheter sets

Irrigation tray

Automatic blood pressure cuff

Electrocardiogram (ECG) leads

Pulse oximeter leads

A comprehensive list of equipment and materials required for the resuscitative phase of trauma care is outlined in Table 1.Equipment necessary for management of the most life-threatening injuries (e.g., airway cart, intubation drugs, and thoracotomy trays) should be stored close to the patient. Other equipment (e.g., mechanical ventilators) may be stored along the walls but should be visible and readily available. In addition, key equipment for procedures should be stored closest to the person performing the procedure (i.e., functional arrangement) or near the region of the body where it will be used (i.e., anatomic arrangement).4 For example, equipment for airway management is best stored near the head of the

stretcher; thoracostomy trays should be located on both sides of the stretcher.5

stretcher; thoracostomy trays should be located on both sides of the stretcher.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree