Chapter 33 Dermatology

Principles of Diagnosis

Initial Evaluation

Although medical school teaches students to perform the history before doing the physical examination, this is not the most efficient way to approach the diagnosis of a skin condition. When the patient has a skin complaint, immediately look at the skin while asking your questions. Look carefully at the lesions and determine the lesion morphology. Table 33-1 provides definitions for the terms used to describe primary and secondary morphology. A magnifying glass and good lighting help to distinguish the morphology of many skin conditions. Next, touch the lesions, with gloves when appropriate. For some lesions, such as actinic keratosis with scaling or the sandpaper rash of scarlet fever, lightly feeling the skin provides much information. For deeper lesions, such as nodules and cysts, deep palpation is needed. Observe the distribution of the lesions. Try to determine if the primary lesions are arranged in groups, rings, lines, or merely scattered over the skin.

Table 33-1 Primary and Secondary Skin Lesions

| Lesions | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary (Basic) Lesions | |

| Macule | Circumscribed flat discoloration (up to 5 mm) |

| Patch | Flat nonpalpable discoloration (>5 mm) |

| Papule | Elevated solid lesion (up to 5 mm) |

| Plaque | Elevated solid lesion (>5 mm) (often a confluence of papules) |

| Nodule | Palpable solid (round) lesion, deeper than a papule |

| Wheal (hive) | Pink edematous plaque (round or flat), topped and transient |

| Pustule | Elevated collection of pus |

| Vesicle | Circumscribed elevated collection of fluid (up to 5 mm in diameter) |

| Bulla | Circumscribed elevated collection of fluid (>5 mm in diameter) |

| Secondary (Sequential) Lesions | |

| Scale (desquamation) | Excess dead epidermal cells |

| Crusts | Collection of dried serum, blood, or pus |

| Erosion | Superficial loss of epidermis |

| Ulcer | Focal loss of epidermis and dermis |

| Fissure | Linear loss of epidermis and dermis |

| Atrophy | Depression in skin from thinning of epidermis/dermis |

| Excoriation | Erosion caused by scratching |

| Lichenification | Thickened epidermis with prominent skin lines |

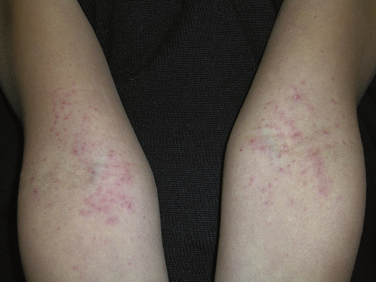

Determine which parts of the skin are affected and which are spared. Be sure to look at the remainder of the skin, nails, hair, and mucous membranes. Patients often show only one small area and appear reluctant to expose the rest of their skin, especially their feet. With many skin conditions, it is essential to look beyond the most affected area because other areas may provide important clues (e.g., nail pitting when considering psoriasis). Patients may have lesions on their back or feet that they have not observed. For example, a patient may have a papular eruption on the hands or arms that represents an autosensitization reaction (id reaction) to a fungal infection on the feet; not looking for the fungus on the feet will lead to a missed diagnosis (Figs. 33-1 and 33-2). Some skin diseases have manifestations in the mouth; finding white patches on the buccal mucosa may lead to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (Fig. 33-3).

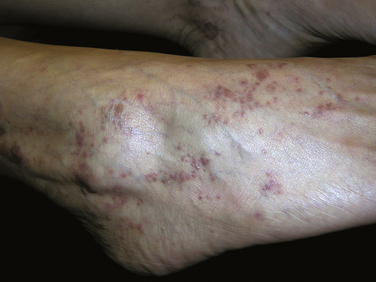

Figure 33-2 Autosensitization reaction secondary to vesicular tinea pedis (id reaction).

(© Richard P. Usatine.)

The most important in-office examinations of the skin are the following:

General Management

Topical Corticosteroids

Table 33-2 Potency of Topical Corticosteroids

| Potency | Generic Drugs | Brand Names |

|---|---|---|

| “Superpotent” (class 1) | Clobetasol, betamethasone dipropionate, halobetasol, fluocinonide | Clobex, Diprolene, Olux, Psorcon, Temovate, Ultravate, Vanos |

| High potency (classes 2 and 3) | Betamethasone dipropionate, mometasone, halcinonide, fluocinonide, desoximetasone, triamcinolone 0.1%, fluticasone, amcinonide | Diprolene, Elocon, Halog, Lidex, Psorcon, Topicort, Aristocort, Cutivate, Cyclocort |

| Midpotency (classes 4 and 5) | Prednicarbate, mometasone, betamethasone valerate, hydrocortisone probutate, fluocinolone, desoximetasone, hydrocortisone valerate, triamcinolone 0.025% | Dermatop, Elocon, Luxiq, Pandel, Synalar, Topicort, Westcort, Cordran, Cutivate, Locoid |

| Low potency (classes 6 and 7) | Alclometasone, desonide, fluocinolone, hydrocortisone | Aclovate, DesOwen, Synalar, Hytone, Desonate |

Management of Pruritus

Often, patients present because of the pruritus associated with a skin condition rather than the skin condition itself. Itching associated with visible lesions often responds to relatively nonspecific antipruritic treatments. If the itching is generalized, patients may obtain temporary relief from cool or tepid baths with the addition of colloidal oatmeal (Aveeno). Soap should be avoided. Oral antihistamines can be given every 6 to 8 hours, especially at bedtime to promote sleep. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril) are first-generation antihistamines that are relatively safe and effective, although caution should be used in older adult patients. Second-generation antihistamines are similarly effective for reducing pruritus in the daytime, and are less sedating for some patients. These include fexofenadine (Allegra), loratadine (Claritin), and cetirizine (Zyrtec). Usually, second-generation antihistamines are given once daily.

Skin Problems Beginning in Childhood

Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

Atopic dermatitis is a common problem affecting up to 15% of all children. In most cases, AD occurs before 5 years of age, frequently on the face in the first year of life (Fig. 33-4). As children grow, the antecubital and popliteal fossae are often involved (Fig. 33-5). The disease may occur intermittently between periods of complete remission. By adulthood, the incidence becomes less than 1%. Treatment should be directed at limiting itching, repairing the skin, and decreasing inflammation. Lubricants and topical corticosteroids are the mainstays of therapy. Topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus are considered steroid-sparing agents and are effective for short-term use or in cases unresponsive to topical corticosteroids. These agents are only approved for second-line treatment in patients over 2 years of age. When required for severe cases, oral corticosteroids can be used. If pruritus does not respond to treatment, other diagnoses, such as bacterial overgrowth or viral infections, should be considered.

Always look for signs of bacterial superinfection, such as weeping of fluid and crusts (Fig. 33-6). Superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus may lead to worsening of atopic dermatitis as the bacteria functions as a super antigen. S. aureus superinfections are usually sensitive to methicillin, so oral cephalexin is frequently a good choice for treatment. Bleach baths are helpful to cut down on colonization. (Add 1⁄2 cup regular bleach per full tub of lukewarm water and soak for 5 to 10 minutes before washing off bleach water.)

KEY TREATMENT

Pityriasis Alba

Pityriasis alba is a common hypopigmented dermatitis that may affect nearly one third of school-age children in the United States. The condition is more common in patients with a history of atopic dermatitis. Patients present with numerous hypopigmented macules ranging from 1 to 4 cm in size on the face, neck, and shoulders (Fig. 33-7). The macules are poorly defined and may have fine scales. Occasionally, erythema and pruritus occur before the lesions. Generally, pityriasis alba is self-limited and asymptomatic, so therapy is typically unnecessary. Lesions usually fade by adulthood. Topical steroids, emollients, and phototherapy have limited efficacy. Hydrocortisone 1% cream or ointment may provide some benefit, and if used for no more than 2 weeks, the patients should be relatively safe from adverse effects.

Melanocytic Nevi

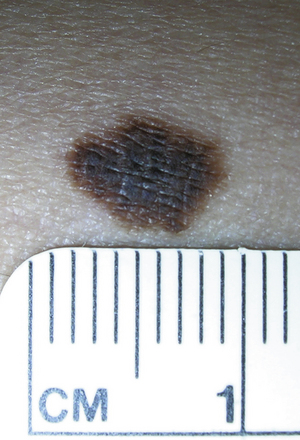

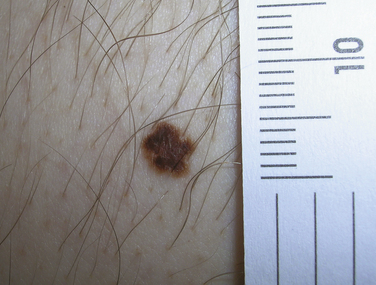

Nevi (moles) are benign lesions composed of collections of nevus cells of neuroectodermal origin. They appear in childhood, tend to increase in number throughout the adult years, and then resolve with age. Pigmented nevi can be flat, raised, or pedunculated and have impressive variations in size, color, and surface characteristics. Histologically, junctional nevi are located in the epidermis, intradermal nevi in the dermis, and compound nevi in the epidermis and dermis. Junctional nevi are flat and pigmented, intradermal nevi are raised and often not pigmented, and compound nevi may be raised and pigmented (Figs. 33-8 and 33-9).

Nevi that are present at birth and are visible shortly thereafter are considered congenital nevi. Although these nevi may have a slightly higher risk of developing melanoma than acquired nevi, it is not cost-effective or sensible to recommend the removal of all congenital nevi. It is even controversial with regard to removal of large, “bathing suit” nevi, which have the highest risk of melanoma. Children born with these nevi are at risk for developing melanoma in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as subcutaneous melanoma, which is not visible and requires palpation in order to detect on routine skin examination.

Dysplastic nevi (atypical moles) are markers for increased risk of melanoma somewhere on the body. These nevi have more atypical features but are not at high risk of converting to melanoma (Fig. 33-10). Therefore, removing dysplastic nevi does not provide a survival benefit for patients. The presence of five or more dysplastic nevi should alert the patient and physician to this higher risk of melanoma, and therefore regular skin examinations should be performed, with sun avoidance and sun protection.

Infantile Hemangioma

A hemangioma is an extremely common type of benign tumor that occurs most frequently in infants and children. It is composed of newly formed blood vessels that result from malformation of angioblastic tissue during fetal life. The two main types are capillary (superficial) and cavernous (deep) hemangiomas (Figs. 33-11 and 33-12).

Acne Vulgaris

Acne is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles on the face, chest, and back. Follicular obstruction leads to comedones, and inflammation results in papules, pustules, and nodules. The four most important steps in acne pathogenesis are (1) sebum overproduction related to androgenic hormones and genetics, (2) abnormal desquamation of follicular epithelium (keratin plugging), (3) Propionibacterium acnes proliferation, and (4) follicular obstruction, which leads to inflammation and follicular disruption. These steps are stimulated by androgens, and strong genetic factors determine a person’s likelihood of developing acne. Although common, acne can cause physical pain, psychosocial suffering, and scarring. Acne may be associated with fever, arthritis, and other systemic symptoms in acne fulminans (Fig. 33-13).

KEY TREATMENT

Viral Exanthems

Varicella

Varicella is now much less common with universal varicella vaccination of children. Occasionally the family physician sees a case of breakthrough chickenpox in a vaccinated child. Unvaccinated adults may also present with varicella. Patients with varicella have fever and general malaise as a mild prodrome lasting 1 to 2 days before the rash appears. The rash typically begins on the face, scalp, or trunk and then spreads to the extremities. The lesions appear as erythematous macules and progress to papules with an edematous base. The papules quickly evolve into vesicles, appearing as “dewdrop on a rose petal” (Fig. 33-15). The vesicles evolve into pustules, which become umbilicated and subsequently crust over in the ensuing 8 to 12 hours. A defining characteristic of varicella is that lesions may be present in all stages simultaneously.

Roseola Infantum (Sixth Disease, Exanthem Subitum)

Roseola infantum, or exanthema subitum, is caused by human herpesvirus 6. This disease occurs in children younger than 3 years. As in fifth disease, the rash of sixth disease appears after the resolution of several days of high fever. The diffuse morbilliform eruption often spares the face and is of short duration, typically fading within 3 days.

Inflammatory Dermatologic Diseases

Seborrhea

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting areas of the head (scalp, face) and body where sebaceous glands are prominent. The inflammation is thought to be caused by Malassezia (Pityrosporum) species. All age groups may be affected, and seborrhea can be chronic or intermittent. On the scalp, seborrhea can range from mild dandruff to thick, adherent plaques. Seborrhea on the face and body appears as greasy scales in skin folds and along hair margins, with a symmetric distribution bilaterally. On the face, two common locations are around the eyebrows and around the beard and mustache in men (Fig. 33-16 and 33-17)

KEY TREATMENT

Psoriasis

Figure 33-20 Guttate psoriasis after streptococcal throat infection in child.

(© Richard P. Usatine.)

Figure 33-22 Palmoplantar psoriasis as a form of localized pustular psoriasis.

(© Richard P. Usatine.)

The most common areas involved include the elbows, knees, extremities, trunk, scalp, face, ears, hands, feet, genitalia, intertriginous areas, and the nails. In most cases, diagnosis of psoriasis is based on the clinical appearance. The differential diagnosis list is long, however, and a KOH preparation or skin biopsy may be needed. A biopsy may also be helpful to establish the diagnosis in less common types of psoriasis (pustular, palmar-plantar, inverse). Do not treat psoriasis with oral or systemic steroids; this can precipitate a life-threatening case of generalized pustular psoriasis.

Etanercept (Enbrel) is a subcutaneous biologic agent that is especially valuable in patients with psoriatic arthritis, as well as those with moderate to severe cutaneous psoriasis (Nast et al., 2007). Adalimumab (Humira), a subcutaneous biologic agent, and infliximab (Remicade), an intravenous biologic agent, are effective for patients with psoriatic arthritis as well as those with moderate to severe cutaneous psoriasis (Bansback et al., 2009). Ustekinumab (Stelara), the most recently approved subcutaneous biologic agent, significantly reduced signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and diminished skin lesions compared with placebo (Gottlieb et al., 2009).

KEY TREATMENT

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a common acute eruption usually affecting children and young adults; the cause is unknown. It is characterized by the formation of an initial herald patch (Fig. 33-24), followed by the development of a diffuse papulosquamous rash. Pityriasis rosea is difficult to identify until the appearance of characteristic, smaller, secondary lesions that follow Langer’s lines in a “Christmas tree” pattern (Fig. 33-25). The rash of pityriasis rosea typically lasts 5 to 8 weeks, with complete resolution in most patients. An important goal of treatment is to control pruritus, which may be severe; zinc oxide, calamine lotion, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines are usually helpful. Systemic steroids are generally not recommended.

Figure 33-25 Pityriasis rosea with “Christmas tree” pattern on back.

(© Richard P. Usatine and E.J. Mayeaux, Jr. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine.)

Rosacea

Papulopustular rosacea presents with acnelike papules and sterile pustules and can occur alone or in combination with the erythema and telangiectasias (Fig. 33-26). Intermittent or chronic facial edema may also occur in all forms. Some patients develop rhinophyma, a coarse hypertrophy of the connective tissue and sebaceous glands of the nose. This can be extremely disfiguring and even cause nasal airway obstruction. Approximately one third of patients with rosacea develop ocular symptoms, including eyes that are itchy, burning, or dry; a gritty or foreign body sensation; and erythema and swelling of the eyelid. The ocular changes can become chronic. Corneal neovascularization and keratitis can occur, leading to corneal scarring and perforation. Episcleritis and iritis have also been reported to occur in patients with rosacea.

KEY TREATMENT

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a papular pruritic skin eruption characterized by its violaceous color and polygonal shape. Most frequently, flat-topped papules and plaques are found on the flexor surfaces of the upper extremities, on the genitalia, around the ankles, and on the mucous membranes (Figs. 33-27 and 33-28). Lesions can be intensely pruritic. Because lichen planus is thought to be immune-mediated, it may be found in conjunction with ulcerative colitis, vitiligo, myasthenia gravis, dermatomyositis, and alopecia areata. Lichen planus is also associated with primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic active hepatitis, and hepatitis C infection.

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a secondary condition that results from repeated mechanical trauma to the skin, usually through rubbing and scratching, which causes lichenification (thickening of epidermis). Skin appears leathery, violaceous to hyperpigmented, and scaly (Fig. 33-29). Involved areas are within the patient’s easy reach, such as arms, legs, posterior neck, upper back, buttocks, and scrotum. The cycle of pruritus, which is alleviated by scratching, perpetuates the condition. Pruritus is usually worse during periods of inactivity, usually at bedtime and during the night. Stress also may provoke pruritus, which is relieved by rubbing and scratching and often becomes an unconscious behavior.

Contact Dermatitis

Contact dermatitis may be classified by cause into two subgroups: irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). ICD occurs when the skin is exposed to an environment or substance in a sufficient frequency, quantity, or duration that it overcomes the barrier function of the skin. Therefore, given adequate exposure, anyone may experience ICD. ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity (type 4) reaction to a topical agent and requires initial contact with a substance causing a T helper cell type 2 (Th2)–mediated immune response in a predisposed individual. Only with repeated exposure do the primed T cells cause the clinical response of dermatitis.

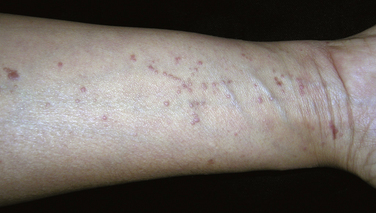

Each year, millions of patients develop an allergic rash after contact with poison ivy, poison sumac, or poison oak, and contrary to popular belief, the fluid within these vesicles does not cause poison ivy “to spread.” Nickel is the most common nonplant cause of ACD and historically more common in women because of costume jewelry and ear piercing (Fig. 33-30). With the increased popularity of jewelry and body piercing, the prevalence is rising in men. The 10 top causes of ACD in North America are nickel, neomycin, balsam of Peru (common fragrance), fragrance mix, thimerosal (preservative no longer used in vaccines but still found in eye preparations), sodium gold thiosulfate, quaternium-15 (preservative), formaldehyde (preservative), bacitracin, and cobalt (metal often in conjunction with nickel in silver-colored jewelry).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree