Delayed Repair of Achilles Tendon Rupture

Keith L. Wapner

Patients with an old or missed Achilles rupture present with complaints of plantarflexion weakness of the ankle during ambulation, climbing, or carrying objects and during other activities of daily life that require push-off power in gait are candidates for late reconstruction (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). Nonsurgical management with footwear modifications, including heel lifts, can alleviate pain but not improve function. Laced-up high-top shoes, boots, or braces, such as a molded ankle-foot orthosis, may improve gait in addition to controlling pain. Work or activity modifications may also be attempted to decrease the demands to plantarflex the foot. These modalities do not restore push-off strength.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Surgery is indicated to restore normal push-off power. Selection of the specific surgical procedure used is determined by analyzing the mechanism of injury, duration of time from the initial injury, and the quality of the tissues. The longer the duration from the initial injury, the less likely a primary end-to-end repair can be performed. In my experience, primary end-to-end repair can be successfully achieved up to 3 months after injury.

Connective tissue disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, obesity, autoimmune disorders, and malnutrition may adversely affect the success of end-to-end repair and may necessitate augmentation. Local factors that make the repair weaker or contribute to postoperative wound problems include ischemia due to peripheral vascular disease, excessive scarring or adhesions from previous surgery, previous infection, and venous insufficiency.

Contraindications for surgery include severe peripheral vascular disease and concomitant medical conditions precluding anesthesia.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The diagnosis is made by reviewing the patient’s history and performing a physical examination. The usual history of an acute rupture is acute onset of pain and inability to rise onto the toes. At the time of rupture, patients often report the sensation of being struck in the calf from behind and experience immediate pain and weakness. The pain may increase as hematoma formation occurs. Patients with systemic connective tissue disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis may relate a more gradual onset, with Achilles tendinosis pain and eventual loss of the ability to rise onto the toes. Tendon rupture from progressive degenerative tendinosis also presents with an insidious course. On examination, active but weak plantarflexion is maintained because of the extrinsic toe flexors, posterior tibial, and peroneal muscles. Misdiagnosis of the time of the rupture can occur in up to 20% of cases. Initially, there may not be an obvious tendon defect, but with time, the ends of the ruptured tendon separate, and the overlying skin conforms to the posterior leg, appearing as a hatchet-type defect. It may appear that there is an overgrowth of the posterior calcaneus

(Fig. 44.1). The Thompson test (i.e., calf squeeze test) result is positive but does not cause as much pain as an acute injury.

(Fig. 44.1). The Thompson test (i.e., calf squeeze test) result is positive but does not cause as much pain as an acute injury.

FIGURE 44.1 The depression in the contour of posterior leg is where the Achilles tendon is ruptured and tendon end retracted proximally. |

The patient with a tendon rupture from progressive degenerative tendinosis presents with an insidious course with progressive thickening of the tendon, progressive lengthening of the tendon, decreased function in push-off, and increased pain. A defect is not evident unless an acute or chronic traumatic rupture occurs. In general, the tendon is markedly thickened and tender to palpation.

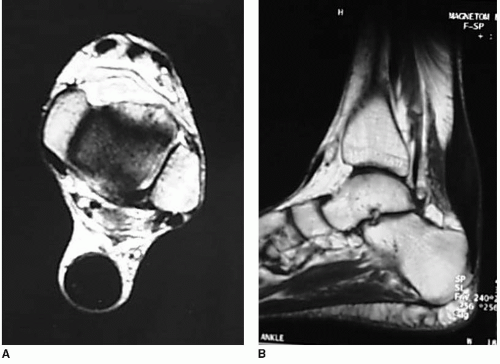

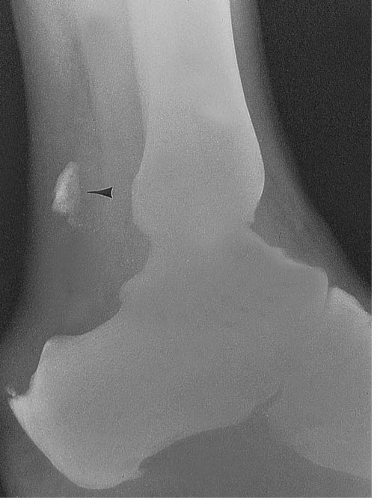

Radiographs should be obtained to exclude avulsion of the posterior tuberosity of the calcaneus (Fig. 44.2), bony deformities, and calcification of the tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in the uncertain diagnosis of an Achilles tendon rupture and chronic tendinosis

(Fig. 44.3). It is most helpful in the sagittal plane to determine the length of tendon injured and to anticipate the type of surgical procedure needed (10).

(Fig. 44.3). It is most helpful in the sagittal plane to determine the length of tendon injured and to anticipate the type of surgical procedure needed (10).

FIGURE 44.2 Proximal migration of an avulsion fracture fragment (arrowhead) from the Achilles tendon insertion. |

The rupture usually occurs 2 to 6 cm from the calcaneal insertion, which is the most avascular region of the tendon. If clinical examination or MRI indicates the defect is less than about 3 cm and if the injury has occurred within the past 3 months, direct end-to-end repair is often possible. If the gap is larger than 3 cm after scar tissue debridement, then V-Y lengthening, Lindholm turn-down procedure, or flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon transfer may be considered to close the gap if the remaining tendon tissue is healthy. If the remaining tendon tissue is not healthy and has chronic tendinosis, augmentation with transfer of the FHL tendon or hamstring can be used.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

V-Y Advancement

Anesthesia should include muscle relaxation to allow for closure of gaps in the tendon. Most procedures are carried out under spinal anesthesia.

The patient is positioned supine, with the foot externally rotated. In patients with limited external rotation place, a bump is placed under the contralateral hip. This allows for easy access to the midfoot if augmentation with tendon graft is indicated. It may also be performed in the prone position.

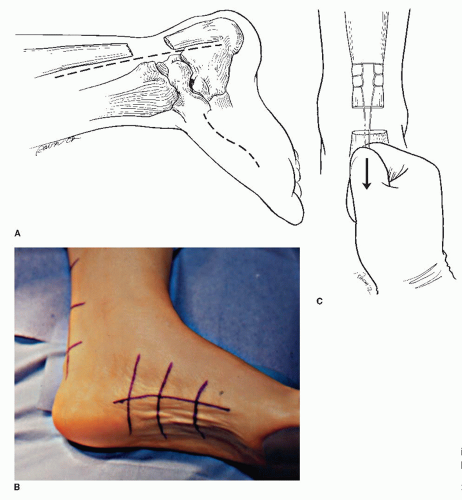

One incision is made in the posteromedial leg along the anterior border of the Achilles tendon extending down to the abductor attachment on the calcaneus, and another is made over the medial distal leg, along the anterior border of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 44.4A and B). This approach avoids irritation of the resulting scar with footwear postoperatively and avoids trauma to the sural nerve.

Dissection is carried through full-thickness down to the level of the paratenon. The surgeon opens the paratenon and dissects to the paratenon to avoid compromising of the skin flaps. The tendon is inspected, and any adhesions are mobilized proximally and distally deep to the paratenon. Assess the size of the gap with knee flexed and ankle plantarflexed. Remove atrophic degenerative tissue down to healthy tissue

To close a gap between the tendon edges, first manually release the adhesions along the course of the tendon deep to the paratenon. Then place a suture from proximal to distal on the medial side of the proximal stump of the tendon extending 3 to 5 cm proximally and then run the suture back down the lateral side. Then wrap the ends of the suture around a Kocher clamp and apply distal traction to the tendon for about 10 minutes (Fig. 44.4C). This will often allow closure of gaps of up to 5 cm as the muscle stretches out and may obviate the need for V-Y advancement. If the gap can be closed, direct repair can be accomplished end to end if the tendon margins ends have viable tissue. If this does not work, consider V-Y advancement.

If the tendon ends are viable and the gap cannot be closed, a V-Y slide or advancement can be used to close the deficiency and lengthen the Achilles tendon to allow end-to-end repair (Fig. 44.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree