Decision Making and Performance of Digital Ray Amputation

Varun K. Gajendran

Harry A. Hoyen

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Ray amputation refers to the ablation of digital elements at or just distal to the carpometacarpal joint of a particular ray. It is most commonly indicated following traumatic injuries, such as partial amputations, failed replantations, or ring avulsion injuries, and also in cases of infection, ischemic gangrene, or as part of a tumor resection. In the pediatric setting, it can also be utilized to close the gap in a congenital cleft hand or to open up the first web space, with the goal of improving functional use of the hand in both cases. A relative contraindication to ray amputation is the availability of alternate procedures that preserve digital length without compromising hand function.

When performed for the appropriate indications, ray amputation can result in a significant improvement in both cosmesis and hand function. It is generally performed as an elective procedure, even in the traumatic setting. If the metacarpal is potentially salvageable, it should be retained at the initial operation in the event that it is needed in the future as a source of spare parts for the reconstruction of other digits. If the metacarpal is not salvageable or it is needed to acutely reconstruct more critical digits such as the thumb, an acute ray amputation may be performed.

There are certain situations where a ray amputation is particularly effective and gratifying for the patient. In cases where the index finger has inadequate length, mobility, or sensation to the point that it is bypassed by the patient or leads to stiffness of the other digits, resection of the index ray can lead to a much more functional hand. A short index finger stump due to amputation at the proximal phalanx or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint level may be converted electively to a ray amputation if the stump interferes with pinch and hand function. Similarly, when there is a short stump of the middle or ring finger left after a partial amputation, it leaves a large cleft in the middle of the hand that allows small objects to slip through and also makes grasping objects difficult. In these cases, a ray amputation of the partially amputated ray, combined with closure of the cleft or transposition, can produce a cosmetically and functionally improved hand.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The preoperative evaluation of a patient scheduled to undergo ray resection includes the standard clinical history and physical examination supplemented with the appropriate imaging studies. For the majority of patients, plain radiographs are sufficient. If a ray resection is being performed as part of the excision of a malignant tumor, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) may help guide incision placement and surgical dissection to ensure negative residual tumor margins. The patient should be counseled preoperatively with respect to the anticipated appearance

and function of the hand. Providing patients with real postoperative photographs before the surgery is particularly helpful. Although most ray resections are performed electively, the specific timing of the procedure is largely dependent on the condition being treated. In the case of a malignant tumor, the procedure should be carried out as early as possible to maximize the chances of obtaining negative margins with a ray amputation. When performed for ischemia and questionable viability of the digit, it may be more appropriate to wait until the necrosis has more clearly “declared itself.”

and function of the hand. Providing patients with real postoperative photographs before the surgery is particularly helpful. Although most ray resections are performed electively, the specific timing of the procedure is largely dependent on the condition being treated. In the case of a malignant tumor, the procedure should be carried out as early as possible to maximize the chances of obtaining negative margins with a ray amputation. When performed for ischemia and questionable viability of the digit, it may be more appropriate to wait until the necrosis has more clearly “declared itself.”

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The procedure can be performed under either general anesthesia or regional anesthesia with sedation, depending on the preferences of the patient, surgeon, and anesthesiologist. The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the arm extended over a hand board. A well-padded nonsterile tourniquet is used. When the operation is being performed for infection or tumor, exsanguination is performed with elevation for several minutes rather than the use of an Esmarch to obviate the theoretical risk of dissemination of the tumor or infection. Loupe magnification should be used to avoid injury to small cutaneous nerves that can lead to neuromas and also to achieve meticulous hemostasis and reduce postoperative swelling.

Although there are subtle differences in the techniques employed for resections of the individual rays, there are many steps that they share in common:

Midline dorsal skin incision over the metacarpal with racket-shaped extensions distally over the proximal phalanx

Division of the extensor tendon at the metacarpal base and reflection of it distally

Subperiosteal stripping of the metacarpal

Carpometacarpal disarticulation or metacarpal base osteotomy

Distal release of the intrinsic tendons on both sides

Division of the deep intermetacarpal ligaments

Dissection of the neurovascular structures on either side of the metacarpal

Division of the flexor tendons, allowing for proximal retraction

Release of all remaining palmar fascia

Ray removal

Proximal division of the neurovascular structures and burial of the nerve in the interosseous space

Transposition or approximation of adjacent remaining rays

Skin flap contouring and closure

Application of dressings and splint

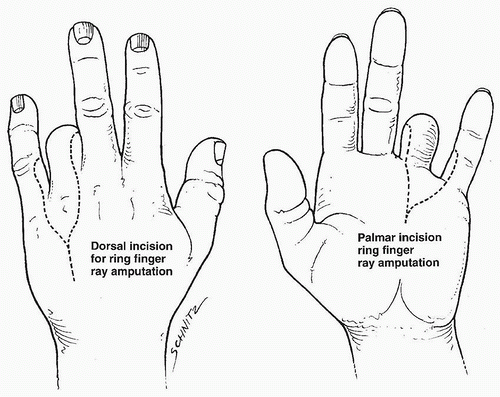

A racket-shaped incision is marked out around the ray to be amputated, which in this example is the ring ray (Fig. 30-1). The incision lies over the dorsal midline of the metacarpal shaft and extends on

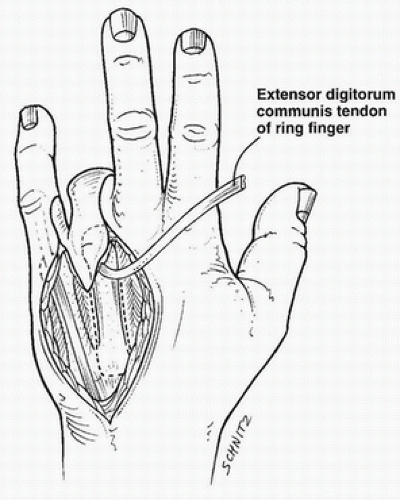

either side around the proximal phalanx to the midproximal phalangeal level. Care is taken to ensure that adequate distal skin is saved for later web closure. This incision may need to be carefully modified in the patient with a malignant tumor to permit complete tumor excision and negative residual tumor margins. The dorsal veins are carefully ligated to obtain hemostasis throughout the approach. The extensor tendons to the amputated ray are divided proximally at the level of the metacarpal base and reflected distally (Fig. 30-2). The juncturae tendinae, if present, are divided such that the extensor tendon can be reflected out to the distal wound margin over the proximal phalanx (Fig. 30-3). The periosteum is incised and stripped around the base of the metacarpal. The metacarpal is then reflected distally.

either side around the proximal phalanx to the midproximal phalangeal level. Care is taken to ensure that adequate distal skin is saved for later web closure. This incision may need to be carefully modified in the patient with a malignant tumor to permit complete tumor excision and negative residual tumor margins. The dorsal veins are carefully ligated to obtain hemostasis throughout the approach. The extensor tendons to the amputated ray are divided proximally at the level of the metacarpal base and reflected distally (Fig. 30-2). The juncturae tendinae, if present, are divided such that the extensor tendon can be reflected out to the distal wound margin over the proximal phalanx (Fig. 30-3). The periosteum is incised and stripped around the base of the metacarpal. The metacarpal is then reflected distally.

FIGURE 30-1 A racket-shaped incision is made as far distally as possible on the proximal phalanx, thereby preserving the adjacent commissures to allow reconstruction of the web during closure. |

In the case of a ring ray amputation, there are no tendinous attachments to the ring metacarpal, and therefore, the entire metacarpal may be removed. In the case of the index, long, and small metacarpals, the base of the metacarpal and the insertion sites of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), and extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), respectively, can be preserved by osteotomizing the base of the metacarpal just distal to the insertions. A power saw is used to complete the osteotomy. Alternatively, the tendinous insertion may be released and the tendon transferred and reattached to the carpus more proximally, although we do not prefer to use this approach.

FIGURE 30-2 The extensor apparatus is reflected distally, and the soft tissues around the proximal metacarpal are subperiosteally elevated. |

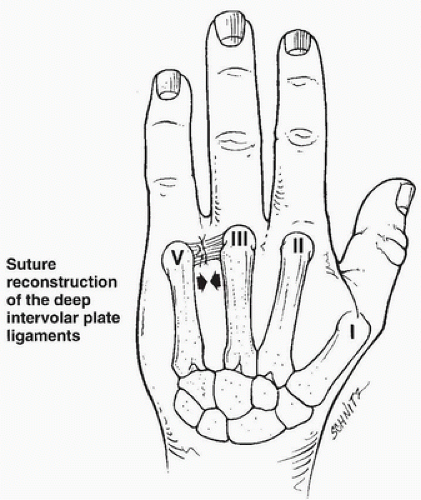

Once the metacarpal is reflected, the dorsal and volar interosseous tendons and radial-sided lumbrical tendons are tenotomized. The deep intermetacarpal ligaments are then exposed and released from the volar plate. The volar portion of the hand incision is then completed (Fig. 30-4). The neurovascular structures are carefully identified and dissected out distally. The digital nerves are divided and tagged for later positioning. The digital arteries are cauterized distal to the takeoff of the branches supplying the palmar skin. The flexor tendons are retracted distally and sharply divided as far proximally as possible, permitting them to retract proximally. The remaining attachments of the palmar fascia are released from the metacarpal shaft. The amputated ray is then removed from the field and passed off as specimen.

The tourniquet is then released and hemostasis is obtained. The residual digital nerve ends are then transposed into the interosseous space vacated by the metacarpal, and the periosteal sleeve is closed around them in an effort to prevent symptomatic neuroma formation. If approximation of the remaining metacarpal shafts is necessary, the deep intermetacarpal ligaments are approximated and sutured together with nonabsorbable suture to draw the metacarpals together (Figs. 30-5 and 30-6).

Transmetacarpal pinning to secure the desired position may be done at the discretion of the surgeon by utilizing two 0.045-inch or 0.062-inch Kirschner wires inserted parallel to one another.

Transmetacarpal pinning to secure the desired position may be done at the discretion of the surgeon by utilizing two 0.045-inch or 0.062-inch Kirschner wires inserted parallel to one another.

FIGURE 30-5 The deep intermetacarpal ligaments are closely approximated, and the skin of the commissure is carefully fashioned to create a new web. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree