Dance

Richard Bachrach

Dancers are a unique form of athlete. Although most injuries seen in dancers are similar to those encountered in all athletes, particularly aerobic exercisers, runners, and gymnasts, many significant differences exist with regard to pathomechanics and approaches to management.

THE DANCER

The physical conditioning achieved by a professional ballet dancer in the corps de ballet is approached by that of only a few world-class athletes. To realize and maintain this razor-sharp neurology and conditioning, the ballet dancer must participate in a minimum of 20 hours of strenuous class work weekly. In a major dance company, this schedule is maintained year round with only brief respites. During rehearsal and performance periods, when the number of classes may be reduced, the schedule becomes even more trying. This environment discourages dancers to disclose injuries until too late, and this affects the dancer’s psyche. The saying goes among ballet dancers: Miss one class and you know it, two classes and the teacher knows it, miss three classes and the whole dance world knows—and there goes the job.

For every ballet job available, there are hundreds of dancers ready and waiting in the wings. An even greater number of jazz and modern dancers await placement in dance worlds that have less support and financing (except for Broadway musicals, which are limited and ever shrinking in number). Therefore, dancers seeking treatment are usually not interested in prescribed rest. Recovery from an injury depends to a significant extent on their confidence in the physician. Confidence can be facilitated if the physician has a working knowledge of the basic dance positions and movements.

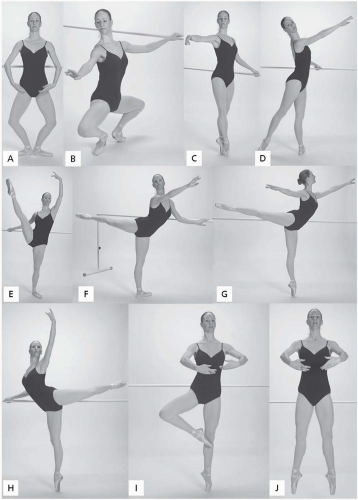

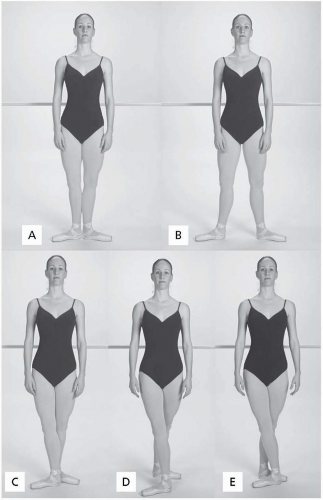

All ballet movements of the lower extremity evolve from one of five basic positions (Fig. 29.1A to E). The ability to assume these positions depends on the amount of external rotation (turnout) available at the coxofemoral joint (Fig. 29.2). Attempts to compensate for decreased range of external rotation at the hip by screwing the knee and/or everting and pronating the foot are the principal alignment fault and the major cause of dance-related injury (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9).

The principal turnout muscles are the gluteus maximus, most hip adductor fibers, and the outward rotators deep to the glutei, which arise from the pelvis and sacrum, and insert into the greater trochanter of the femur. The principal structural determinants of the range of external rotation at the hip joints are the iliofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments (together forming the Y ligament of Bigelow, the strongest ligament in the body), and the angle between the neck and shaft of the femur when seen from above. This angle (version) ranges from +40 to -20. The hip with a greater angle has greater range of internal rotation, while less anteversion increases the range of external rotation (7,10). Because mature ligaments do not stretch without tearing, stretching a ligament compromises the integrity of the joint involved. For these reasons, an individual who starts dance training after the age of 10 or 11 cannot be expected to structurally increase turnout (7,11).

The following movements derive from one of five basic ballet positions (Fig. 29.1A to E). Their proper execution depends on the turnout effected at the hip and on proper alignment.

FIGURE 29.1. Positions of ballet. A, First position. B, Second position. C, Third position. D, Fourth position. E, Fifth position. |

Demi-Plié (pli, fold [French]). (Fig. 29.3A). This movement may take place in any of the five basic positions on both or one leg. The knees, hips, and ankles are flexed, and the full foot rests on the floor. This lowers the center of gravity, stretches the soleus component of the triceps surae, and thus prepares for air work. It involves concentric contraction of the hip flexors, abductors, and external rotators. There is concentric contraction of the hamstrings at the knee and concentric contraction of the dorsiflexors of the foot and toes. The hip adductors and proximal hamstrings contract eccentrically. Contraction of the quadriceps (except the rectus femoris at the hip) and the peroneus longus, tibialis posterior, and flexor hallucis longus is also eccentric. The depth of the demi-plié is limited by the tension in the soleus muscle and by the abutment of the anterior margin of the distal tibia on the neck of the talus. The patella is compressed against the femoral trochlea. In a properly executed demi-plié, the center of gravity moves directly downward through the legs, the knees passing directly over the feet in the same plane.

Grande-Plié (Fig. 29.3B). In this movement, the center of gravity descends further. The amount of flexion at the knees, hips, and ankles is increased, and the heels are finally lifted from the floor. Extreme stress is put on the knee, particularly components of the patellofemoral and medial tibiofemoral compartments.

Relevé (Fig. 29.3C). While the plié is a vertically downward movement of the center of gravity, the relevé facilitates ascent of the center of gravity, at the same time shifting the body weight to the ball of the foot (in the case of advanced or professional female ballet dancers, to full pointe). It requires active concentric contraction of the long plantarflexors of the foot, toes, and ankle, and also of the quadriceps, because it is usually executed with the knee extended. There is simultaneous eccentric or lengthening contraction of the hamstrings. The deep external rotators and the glutei concentrically contract to stabilize turnout throughout the movement. The adductors eccentrically lengthen to allow for abduction at the hip.

Pointe. Unless a dancer is an aspiring professional female ballet dancer, she will infrequently confront this position. Nevertheless, full pointe is the end point of the relev. In the presence of a long posterior process of the talus or os trigonum tarsi, this position is difficult to attain and is painful in the posterior triangle. There is less strain on the triceps surae en pointe than in relev to half-toe. Ankle stability with the foot en pointe is provided by the flexor hallucis longus and posterior tibial and peroneal (stirrup) muscles.

Tendu (Battement Tendu) (Fig. 29.3D). This movement is a sequential plantarflexion of the foot as it slides along the floor, until only the tips of the toes remain in contact. (The heel leads the movement until it is forced to release from the floor.) The leg remains straight, with active eccentric contraction of the hamstrings. The leg returns to its starting position in a reverse sequence. (When the same movement is performed with the foot brushing off the floor, it is termed dégag, meaning to disengage.) These movements are executed also to the side and back and are essential elements of the ballet barre.

Développé (Fig. 29.3E). This movement is almost always performed with full outward

rotation at the hip. The thigh folds into 90 degrees of flexion at the hip. Simultaneously, the knee also flexes and the foot is drawn up the medial aspect of the standing leg to the knee. Retaining hip flexion, the knee is then extended fully, either to the front, side, or back. Développé front requires active concentric contraction of the hip flexors, in particular the iliopsoas and the rectus femoris. Of primary importance is the sartorius, whose concentric contraction assists in flexion at the hip joint, flexes the knee, and outwardly rotates the thigh during the preparatory action. The hamstrings first concentrically contract to flex the knee, and then eccentrically lengthen during the extension of the leg, as do the gluteals. The external rotators contract to maintain the outward rotation, both on the supporting leg and also on the gesturing leg.

Grand Battement (Fig. 29.3F). This is often referred to by the dancer as an extension and involves simultaneous flexion of the hip to at least 90 degrees with the knee maintained in extension. This movement is usually performed with some speed but may also be done slowly. It is essentially an amplified tendu and dégag, passing through these two movements with the leg sweeping straight up. Proper execution requires concentric contraction of the hip flexors, particularly the iliopsoas and rectus femoris. The quadriceps contract concentrically to straighten the knee, and the triceps surae, tibialis posticus, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus, and peroneals do likewise to plantarflex the foot. There is simultaneous lengthening of the hamstrings. Like the développé, this movement may be executed to the front, to the side, and to the back.

This may be a good time to introduce dance speak. When a dancer says I have a great extension, he or she means that the range of hip flexion with the knee extended is unusual. When a dancer speaks of a foot being flexed, it refers to dorsiflexion. Plantarflexion is referred to as pointing or extending. Pointing, combined with excessive lateral deviation of the forefoot, is referred to as winging, or sickling out. This represents a technique defect, as does its opposite (sickling in) (7,10,12).

Arabesque (Fig. 29.3G). This beautiful, graceful, and extremely difficult position is characterized by carrying the leg, which is fully extended at the knee, past 90 degrees posteriorly. The foot is pointed and the hip is fully extended in a position in which the iliofemoral ligament is most taut. The lumbosacral junction must be hyperextended, and there is marked torsion of the pelvis on the spine. On the supporting side, the knee is straight (unless plié is performed), and the foot is parallel to the pelvis. This is an extremely difficult position to attain and sustain, requiring concentric contraction of hip external rotators to maintain outward rotation on both legs. The hip flexors, including the rectus femoris, must eccentrically lengthen across the coxofemoral joint, while the latter joint, with the other quadriceps, must concentrically contract to extend the knee, while the hamstrings and gluteals contract concentrically at the hip. The hamstrings must lengthen across the back of the knee. Technique faults are recognized by excessive pelvic torsion and/or failure to keep the knee of the gesturing leg fully extended and the foot pointed.

Attitude (Fig. 29.3H). The path out to this position is similar to that of développé, except that full extension of the leg does not occur. Rather, the dancer reaches a point at which the leg is held with the hip flexed greater than 90 degrees and the knee flexed 90 degrees. This position can also be reached from grande battement, or from any other movement, and may be executed to the front, side, or back.

Pirouette or Tour (including fouett, attitude, etc.; Fig. 29.3I). These are turns executed on one foot usually beginning from a demi-plié in one of the five basic positions. The weight is then shifted over the ball of the foot of the supporting leg, simultaneously moving into relevé, beginning the

turn, and positioning the gesturing leg. The execution of the turn depends on how centered the dancer is over the supporting leg. This, in turn, is largely dependent on the strength and development of the stirrup muscles, that is, the flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus, and the tibialis posterior medially, and the peroneus longus and brevis laterally.

Jumps (Fig. 29.3J). Whether off one or both feet, the preparatory position for all jumps is the demi-plié. The higher the jump, the deeper the plié must be. Powerful contractions of the gluteus maximus extend the thigh and the hip; the quadriceps femoris extends the knees, and the triceps surae and other plantarflexors point the feet and toes. In landing, the dancer passes through the ball of one or both feet, releasing the lower extremities into flexion moving back into demi-plié.

There are many more ballet positions and movements, but a firm grasp of the above-mentioned information will improve your ability to communicate with the injured dancer and help you to understand the demands placed on him or her. This should facilitate management of a wide range of orthopedic problems affecting the great number of people involved in dance.

DANCE INJURIES RELATED TO LUMBOPELVIC SOMATIC DYSFUNCTION

All dance injuries are the result of faulty technique, excluding those caused by adverse environmental factors, malfeasance of fellow dancers, and choreography involving movement beyond the range of human achievement (3). In turn, these are usually the result of maladaptive movement patterns secondary to nonfacilitative alignment. The principal sources of the last two are listed in Table 29.1.

Most dance injuries involve the foot, ankle, or knee. They are profoundly interrelated, both to each other and to dysfunction of the low back and pelvis. The most common site of muscular dance injury is the lower back (2). The majority of soft tissue back injuries are related to strength-length disparity between the trunk and hip flexors and extensors, and between the internal and external hip rotators. These imbalances may be secondary to lumbar articular facet joint capsule and sacroiliac ligament laxity, which in turn may be the cause or effect of intervertebral disc pathology (4).

TABLE 29.1. PRINCIPAL SOURCES OF FAULTY TECHNIQUE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abdominal Wall

The abdominal muscles can be divided into three groups: (a) lateral, including the external and internal obliques and the transversus abdominis; (b) medial, including the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis; and (c) deep, situated anterior to the vertebral column, the iliopsoas (IP), and the quadratus lumborum (QL). The IP is important in all forward motion. The lateral and medial muscles serve to support the abdominal contents by forming the anterior wall of the abdominal cavity. They lower the ribs and elevate the anterior rim of the pelvis, assist in flexing the trunk on the hips, and assist in side bending or twisting. They also rotate the trunk with the lower extremities fixed and, most importantly, during respiration their contraction elevates intra-abdominal pressure, supporting the trunk anteriorly, thus assisting in maintaining verticality.

The QL is a quadrangular sheet of muscle arising from the posterior iliac crest, transverse processes of the lower lumbar vertebrae, and iliolumbar ligament. It extends to the twelfth rib and the costal processes of the upper lumbar vertebrae. It primarily stabilizes the neutral lumbar spine, lowers the twelfth rib, raises the

ipsilateral iliac crest, and flexes the body to the side of the contraction. Unlike the other abdominal muscles, bilateral QL contraction extends the spine (13).

ipsilateral iliac crest, and flexes the body to the side of the contraction. Unlike the other abdominal muscles, bilateral QL contraction extends the spine (13).

The psoas major (PM) and iliacus (IL) (arising from the sacrum and the iliac fossa) are the primary flexors of the hip. They join together near the femoral head to form the ilopsoas. Secondary hip flexors include the rectus femoris, pectineus, sartorius, adductors, tensor fasciae latae, and anterior fibers of the gluteus medius and minimus. The PM is vitally involved in low back and postural mechanics and thus of primary concern not only in low back injury, but in almost all dance injuries. The PM arises in a series of slips from the vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs, and transverse processes of the last thoracic and the five lumbar vertebrae and the tendinous arches over the lateral bodies of L1-L4. It courses diagonally downward, forward, and slightly outward, crosses the front of the hip joint, and runs caudad and posteriorly to join the iliacus in a common tendon insertion into the lesser trochanter of the femur.

With the lower extremities fixed and the muscles acting from downward up, the PM and IL side bend the trunk, flex the trunk at the hip, and pull the lumbar vertebrae anteriorly, which increases the lordosis and extends the pelvis on the spine. Acting in the opposite direction (from above downward), the psoas flexes, externally rotates, and adducts the free thigh at the hip.

However, with the leg fixed (most significant in relation to dance injuries) working in concert with the internal rotators, the PM externally rotates the trunk on the standing femur so as to advance the opposite side in walking, in effect becoming an internal rotator of the ipsilateral femur. Thus, when the PM is shortened, it has the following effects in dancers:

Exerts a prolordotic action on the lumbar spine promoting vertebral facet joint approximation and impingement, which destabilizes the sacroiliac joints (SIJs) (14).

Restricts weight-bearing hip external rotation (turnout) particularly at the end range.

Restricts extension at the hip (promoting anterior pelvic rotation). This is of major significance in the causation of dance injuries (5).

Michele’s Test (adapted from Arthur Michele) (9)

Rationale: This is a modified version of the Thomas test for iliopsoas tension, but with more sensitivity for dancers, since they typically have joint ranges of motion that render the Thomas test negative.

Contraindications to test: Low back or lower extremity pain strongly suggests lumbar disc pathology, while acute psoas spasm is an obvious contraindication to the maneuver (3).

The dancer lies with hips and knees flexed fully at the end of the table.

While the dancer grasps the left knee, clutching it as close as possible to the chest without discomfort, the examiner extends the right knee so the lower extremity is now as near to the perpendicular as feasible and comfortable.

The right leg is then extended on the hip, supported by the examiner’s right hand, while the left hand monitors the anterior superior iliac spine.

The extended leg is lowered passively until the point at which anterior rotation of the innominate is palpated. At that point, the angle that the lower extremity makes with the horizontal is recorded as the degree of psoas tightness. The dancer should be able to attain 10 degrees of extension (below the horizontal) with the knee extended (Fig. 29.4).

Positive test: Inability to extend one hip to less than 30 degrees from the horizontal (without concomitant anterior rotation of the innominate), enough to cause symmetrical or asymmetrical anterior pelvic rotation with sacroiliac joint instability and dysfunction.

Indicates: Significant hip flexor tightness.