This article reviews mobility technology in less-resourced countries, with reference to people with disabilities in several locations, and describes technology provision to date. It also discusses a recent collaborative study between a United States University and an Indian spinal injuries hospital of Indian wheelchair users’ community participation, satisfaction, and wheelchair skills. The data suggest that individuals who received technology from the hospital’s assistive technology department experienced increased community participation and improved wheelchair skills. This evidence may have already enabled the hospital to improve Indian governmental policies toward people with disabilities, and it is hoped that future research will benefit other people similarly.

Many rehabilitation specialists understand that in lower-income countries, the need for assistive technology (AT) outweighs availability; research and development are called for. Since the publication of the earliest papers, appropriate technology for people with disabilities (PWD) has, to a limited extent, become more available and of better quality. International convention has recognized the need for progress toward the inclusion of PWD in their communities through a social model of disability. Although there remains a great deal of work to meet the needs of millions worldwide, better tools and technologies are in development. This paper provides an overview of the work that has been done thus far in low- and middle-income countries, including recent research carried out by the authors’ laboratory in collaboration with the Indian Spinal Injuries Centre in New Delhi.

Snapshots

Although appropriate technology is scarce throughout much of the world, varying political stability, national resources, and societal attitudes affect the lives of PWD. Although rehabilitation specialists often talk in terms of “technology for less-resourced environments,” the situation in each country is different and may need to be evaluated on its own terms. This section gives examples of several countries in various stages of progress for PWD.

Afghanistan

In recent decades, Afghanistan has experienced political upheaval and violence. Years of civil war have left the country littered with landmines, and consequently with a large number of amputees. Historically, some provision of AT was given to men with amputations, although this service was not rendered to women or individuals with other types of orthopedic disabilities. Taliban rule forbade employment of women, which compromised the quality of health services. Traditional societal views and isolation from international convention have contributed to a lack of social progress with respect to disability. War wounds frequently disable men, and the deterioration of infrastructure and services has taken its toll on the physical and mental well-being of women and children. An effort was made to include women in a study to evaluate a wheelchair designed for Afghanistan ; however, among those recruited, women were still a minority.

There have been several internal and international efforts to bring relief to this situation. The Physical Therapy Institute in Kabul trains therapists, although employment of these approximately 200 individuals is concentrated in urban areas. The Rehabilitation of Afghans with Disability (RAD) program trains physical therapy assistants to work in rural areas and implements several rehabilitation programs. Even with these efforts, the physical therapy needs of the Afghan people are not well met.

India

India is an emerging economic power where poverty, accessibility barriers, and repair resources present challenges to wheelchair use. However, the Indian government is concerned with promoting the welfare of its citizens with disabilities. The Persons with Disabilities Act of 1995 was passed to protect PWD in education, employment, and other situations in which they encounter discrimination. Implementation of this act is difficult, as is the enforcement of much of India’s human rights legislation. However, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment’s Assistance to Disabled Persons for Purchase (ADIP) Scheme is intended to assist PWD with acquiring AT, and parts of India’s infrastructure, such as the buses in New Delhi, are slowly being made wheelchair accessible.

Kosovo

One of the world’s newest nations faces the challenge of rebuilding a health care system after decades of soviet bureaucracy and war. When the country was part of Yugoslavia, the health care system was hierarchical and inefficient. Since Kosovo gained its independence from Serbia, it has begun to develop its own health care system. Kosovo still struggles to care for the health needs of all its citizens, and consequently support for PWD is limited.

Because Kosovo is focused on its survival and stability, the government has few resources to devote to service provision. The nongovernmental organization HandiKOS (Association of Paraplegics and Paralysed Children of Kosovo) attempts to fill this void by distributing AT, educating PWD and their communities, and encouraging networking among families concerned with similar disabilities. However, the effectiveness of HandiKOS is dependent on the support of charitable foundations and the availability of other resources for PWD in Kosovo. HandiKOS continues to lobby the government for public services.

Zimbabwe

Before the recent collapse of Zimbabwe’s economy, the country had one of the more advanced and progressive rehabilitation systems in the developing world. Two parallel sectors existed: the informal sector of traditional medicine and rehabilitation techniques, and the formal, Western-oriented sector that had remained in Zimbabwe since British colonial rule. Each sector eyed the other with suspicion and lack of respect, and referrals between the 2 were limited. However, PWD enjoyed a level of acceptance within their families and communities. Disability was not viewed as inherently isolating. Although access to disability services was in part determined by socioeconomic status and in particular living location (urban vs rural), Zimbabweans overall enjoyed some presence of services.

Recent political upheaval and economic turmoil in Zimbabwe have made necessities such as food and sanitation scarce, and it is uncertain if much rehabilitation is being conducted. Zimbabwe’s history of social inclusion of PWD may facilitate recovery of the rehabilitation system, if the country stabilizes enough that its people can focus on more than basic survival. However, “health in Zimbabwe is presently largely unavailable, unacceptable, inaccessible and of poor quality.”

Provision efforts

Provision Models

Several approaches have been taken to providing wheelchairs in less-resourced countries. These include the “charitable model,” “workshop model,” “manufacturing model,” “globalization model,” and a fifth model that integrates aspects of the other 4 according to the needs of local people.

In the charitable model, organizations donate wheelchairs in mass numbers to people in lower-income countries. Some charities provide used wheelchairs with or without custom fitting and local repair efforts. The Free Wheelchair Mission (FWM) donates a proprietary wheelchair model that is mass produced in China and shipped throughout the world. The wheelchair, which can be distributed for about $52 USD, has a seat made from a plastic lawn chair. In recent years, a thin foam seat cushion has been included, although concerns about complications such as pressure ulcers remain. One study reported modest benefits to participation, pain, and skin health among recipients of FWM wheelchairs in India and Peru; however, this study was retrospective rather than longitudinal (surveys were not conducted before the wheelchair was received). The study found that only 11.7% of individuals used their wheelchair more than 8 h/d. This is in contrast to wheelchair users in the United States, who spend an average of more than 12 h/d in their wheelchairs.

Charitable donations of used wheelchairs have been criticized for providing technology that cannot be maintained locally, undercutting efforts to develop sustainable sources of wheelchair provision. Donated wheelchairs are quickly abandoned or rarely used because of poor fit and comfort, rapid breakdown of chairs, and inaccessibility of the local environment.

Workshop and manufacturing model enterprises involve the establishment of local wheelchair fabrication facilities. They have the potential to be sustainable, produce wheelchairs that are less expensive than imported equipment, and provide employment for local wheelchair users. However, they are subject to local economic influences, including competition from charitable wheelchair donations. Individuals assisting with the establishment of these shops must be prepared to teach wheelchair building and seating skills using methods that convey knowledge effectively to members of the local community.

In the globalization model, an established wheelchair manufacturer builds or imports wheelchairs in an emerging market. This model can be sustainable and effective provided the product and sale cost are appropriate for the local community. A “multimodal” model combines various strategies according to what works in a particular region, and allows efforts to be scaled depending on what is feasible. In this model, the need for wheelchairs in a region may be addressed by several different providers using diverse approaches.

Design Efforts

There have been numerous efforts by researchers to design mobility technology appropriate for less-resourced environments. It is unknown how many have been successful. The most familiar organizations and technologies are those that have a large presence in rehabilitation literature or on the Internet. These include a ground-level mobility device, a manual wheelchair, a pediatric tilt-in-space wheelchair, and a low-cost electric-powered wheelchair, which were all designed with a focus on India. The ground-level mobility device was given to local developers after the initial research (Susan J. Mulholland, personal communication, 7 June 2009). Freely available designs have made it obtainable in India and other countries such as Nepal, where it is produced (Joy Wee, personal communication, 27 June 2009). Several wheelchair designs appear in the book Disabled Village Children and can be built with simple materials and techniques ( Fig. 1 ). Hope Haven’s KidsChair wheelchair incorporates seating supports for individuals with varying postural needs.

Whirlwind Wheelchair International has established itself as a network of independent wheelchair shops around the globe. Whirlwind’s staff serve to integrate design concepts gathered from innovators throughout the network. The result has been a series of wheelchair designs intended for regions in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. A study to evaluate a wheelchair specifically designed for people in Afghanistan found that users ranked the study wheelchair significantly higher than their original wheelchair in ease of propulsion, stability, transportability, seating comfort, and appearance. For many years, Whirlwind has offered a wheelchair construction class at San Francisco State University. Similarly, a class at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “Wheelchair Design in Developing Countries” (SP.784), addresses the improvement of appropriate wheelchairs and mobility tricycles.

Motivation Charitable Trust, from the United Kingdom, contributes in mobility technology, advocacy, community employment programs, and training. Motivation has created the Worldmade brand, a wheelchair-provision process that combines mass production, flat packing, and on-site fitting. These chairs, although mass produced, are designed such that their configuration can be customized upon assembly. The Worldmade 3-wheel wheelchair, which was designed with rural areas in mind, has customizable seat width, seat depth, backrest height, footrest height, footrest position, and drive wheel axle position.

Freedom Technology, a wheelchair and tricycle shop based in the Philippines, offers a comprehensive line of everyday, sport, geriatric, and pediatric wheelchairs and tricycles. The company values quality and appropriateness of its technology and has conducted user research to assess its products. This research concluded that a tricycle may best benefit someone with limited walking or crawling ability, that the tricycle should be able to be used easily over rough terrain, that it should support the user and be ergonomic, that it should be configurable to be used with significant cargo, and that repair frequency and costs should be comparable to a standard bicycle.

In Nicaragua, Mobility Builders focuses particularly on children with complex seating needs, many of whom come from the poorest of families. They use a combination of clinical evaluation, computer-aided design, and local wheelchair fabrication to bring mobility to these children. Mobility Builders is an offshoot of The Wheelchair Project, a broader organization that raises funds to buy wheelchairs for those in need, trains therapists, and advocates for children’s medical care.

Provision efforts

Provision Models

Several approaches have been taken to providing wheelchairs in less-resourced countries. These include the “charitable model,” “workshop model,” “manufacturing model,” “globalization model,” and a fifth model that integrates aspects of the other 4 according to the needs of local people.

In the charitable model, organizations donate wheelchairs in mass numbers to people in lower-income countries. Some charities provide used wheelchairs with or without custom fitting and local repair efforts. The Free Wheelchair Mission (FWM) donates a proprietary wheelchair model that is mass produced in China and shipped throughout the world. The wheelchair, which can be distributed for about $52 USD, has a seat made from a plastic lawn chair. In recent years, a thin foam seat cushion has been included, although concerns about complications such as pressure ulcers remain. One study reported modest benefits to participation, pain, and skin health among recipients of FWM wheelchairs in India and Peru; however, this study was retrospective rather than longitudinal (surveys were not conducted before the wheelchair was received). The study found that only 11.7% of individuals used their wheelchair more than 8 h/d. This is in contrast to wheelchair users in the United States, who spend an average of more than 12 h/d in their wheelchairs.

Charitable donations of used wheelchairs have been criticized for providing technology that cannot be maintained locally, undercutting efforts to develop sustainable sources of wheelchair provision. Donated wheelchairs are quickly abandoned or rarely used because of poor fit and comfort, rapid breakdown of chairs, and inaccessibility of the local environment.

Workshop and manufacturing model enterprises involve the establishment of local wheelchair fabrication facilities. They have the potential to be sustainable, produce wheelchairs that are less expensive than imported equipment, and provide employment for local wheelchair users. However, they are subject to local economic influences, including competition from charitable wheelchair donations. Individuals assisting with the establishment of these shops must be prepared to teach wheelchair building and seating skills using methods that convey knowledge effectively to members of the local community.

In the globalization model, an established wheelchair manufacturer builds or imports wheelchairs in an emerging market. This model can be sustainable and effective provided the product and sale cost are appropriate for the local community. A “multimodal” model combines various strategies according to what works in a particular region, and allows efforts to be scaled depending on what is feasible. In this model, the need for wheelchairs in a region may be addressed by several different providers using diverse approaches.

Design Efforts

There have been numerous efforts by researchers to design mobility technology appropriate for less-resourced environments. It is unknown how many have been successful. The most familiar organizations and technologies are those that have a large presence in rehabilitation literature or on the Internet. These include a ground-level mobility device, a manual wheelchair, a pediatric tilt-in-space wheelchair, and a low-cost electric-powered wheelchair, which were all designed with a focus on India. The ground-level mobility device was given to local developers after the initial research (Susan J. Mulholland, personal communication, 7 June 2009). Freely available designs have made it obtainable in India and other countries such as Nepal, where it is produced (Joy Wee, personal communication, 27 June 2009). Several wheelchair designs appear in the book Disabled Village Children and can be built with simple materials and techniques ( Fig. 1 ). Hope Haven’s KidsChair wheelchair incorporates seating supports for individuals with varying postural needs.

Whirlwind Wheelchair International has established itself as a network of independent wheelchair shops around the globe. Whirlwind’s staff serve to integrate design concepts gathered from innovators throughout the network. The result has been a series of wheelchair designs intended for regions in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. A study to evaluate a wheelchair specifically designed for people in Afghanistan found that users ranked the study wheelchair significantly higher than their original wheelchair in ease of propulsion, stability, transportability, seating comfort, and appearance. For many years, Whirlwind has offered a wheelchair construction class at San Francisco State University. Similarly, a class at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “Wheelchair Design in Developing Countries” (SP.784), addresses the improvement of appropriate wheelchairs and mobility tricycles.

Motivation Charitable Trust, from the United Kingdom, contributes in mobility technology, advocacy, community employment programs, and training. Motivation has created the Worldmade brand, a wheelchair-provision process that combines mass production, flat packing, and on-site fitting. These chairs, although mass produced, are designed such that their configuration can be customized upon assembly. The Worldmade 3-wheel wheelchair, which was designed with rural areas in mind, has customizable seat width, seat depth, backrest height, footrest height, footrest position, and drive wheel axle position.

Freedom Technology, a wheelchair and tricycle shop based in the Philippines, offers a comprehensive line of everyday, sport, geriatric, and pediatric wheelchairs and tricycles. The company values quality and appropriateness of its technology and has conducted user research to assess its products. This research concluded that a tricycle may best benefit someone with limited walking or crawling ability, that the tricycle should be able to be used easily over rough terrain, that it should support the user and be ergonomic, that it should be configurable to be used with significant cargo, and that repair frequency and costs should be comparable to a standard bicycle.

In Nicaragua, Mobility Builders focuses particularly on children with complex seating needs, many of whom come from the poorest of families. They use a combination of clinical evaluation, computer-aided design, and local wheelchair fabrication to bring mobility to these children. Mobility Builders is an offshoot of The Wheelchair Project, a broader organization that raises funds to buy wheelchairs for those in need, trains therapists, and advocates for children’s medical care.

Recent research in India

Introduction

Many similarities exist between the needs of wheelchair users worldwide, such as the need for access, appropriate seating and mobility, and employment opportunities. However, the specifics are not universal. Infrastructure accessibility and employment opportunities vary widely, and the appropriateness of technology depends on the environment and aspects of local culture (eg, where cooking is done). Thus, to serve PWD properly in a given location, it is important to understand the specific needs of individuals.

Although proponents of the various provision models believe in the effectiveness of their own efforts, there exists little reliable evidence to indicate that one strategy is superior to another. There has been praise for one type of wheelchair and complaints about another, but these are anecdotes and may not represent the totality of wheelchair-provision outcomes. Stronger evidence would come in quantitative data that evaluates many outcomes in a region during a period of time. Ideally, this evidence would be collected using a standard survey tool appropriate for widespread use, so that results could be compared across regions and service-delivery techniques.

Some of the technology development in the authors’ laboratory has focused on India, as has the research presented in this article. Community participation, life satisfaction, wheelchair skills, and technology satisfaction were studied among clients of the Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (ISIC) who received new AT.

ISIC is one of a few locations in India where wheelchairs are clinically prescribed. The Department of Assistive Technology (DAT) has collaborated with the authors’ laboratories for several purposes: (1) to assess the impact of AT in India, (2) to improve clinical provision at the ISIC DAT by evaluating the effectiveness of its practices, and (3) to pilot the collection of such data in less-resourced environments. The authors hypothesized that the provision of new AT to clients of the hospital would increase their community participation and life satisfaction, and also that the provision of clinician-evaluated wheelchairs would immediately increase wheelchair skill proficiency and technology satisfaction.

The authors aim to improve the level of evidence available to support appropriate mobility technology. With this evidence, providers such as the ISIC DAT should be able to improve their quality of care and inform donors, providers, and designers about which AT makes the most impact on the people who use it.

PART survey: participation and life satisfaction of Indian wheelchair users

The World Health Organization (WHO) has taken a lead in promoting a holistic approach toward disability. WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) considers disability to be a result of the interaction between a person’s body and the environment. Body functions, body structure, activity, and participation are taken into account. Because “an individual’s functioning and disability occurs in a context,” a person with a particular impairment will live a unique life depending on socioeconomic status, educational work opportunities available, perception of the impairment by others, and any number of other factors. Furthermore, the ICF recognizes the concept of parity, in which the repercussions of an impairment are largely independent of the cause of that impairment (eg, limb losses caused by landmines and illness have similar consequences). The ICF was designed to complement the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system, which classifies health conditions without addressing the repercussions of those conditions.

Recently WHO, in collaboration with other international agencies, published a best practices guidebook for manual-wheelchair provision. The book emphasizes the effects of appropriate technology on the health and happiness of wheelchair users, supplementing provision information with profiles of individuals who have benefited from wheelchairs. The message of many of these anecdotes is that appropriate technology benefits participation in the community.

In addition to the best practice evidence, substantial research has been carried out in the area of participation. Vissers and colleagues investigated barriers to physical activity after spinal cord injury (SCI). This study found evidence that the logistical needs of individuals with SCI dominate immediately following injury, whereas social, economic, and health maintenance issues dominate in the long term. In other words, depending on the time since disability onset, different issues may predominantly influence physical activity. After self-care challenges become routine, physical and social public barriers seem most limiting. Similarly, Chaves and colleagues found that wheelchair users with SCI in 2 US cities identified mobility technology as the most limiting factor to overall participation, even compared with the physical impairment. Participants in this study were an average 14±9 years post injury. Chaves and colleagues’ findings agree with those of Vissers and colleagues, in that individuals accepted their physical impairments in time and became more frustrated with the inadequacies of available technology (the wheelchair) and infrastructure (concerning environmental accessibility, or that which the wheelchair cannot traverse). Other studies have also identified AT and adaptations as facilitators to participation. Shoulder pain has been shown to correlate with decreased participation among men with SCI and standard practice guidelines recommend a customizable wheelchair that is as lightweight as possible to reduce the risk of pain and injury in the upper extremities. Thus, there is an established influence of pain and barriers on participation, with technology as a known mediating factor.

To benefit the Indian population, with and for whom the authors have developed several wheelchairs, it is important to understand the influence of such technology on their lives. Though appropriate technology may have similar effects worldwide, factors such as the wheelchair user’s physical environment, and the social role of the person with the disability, will likely influence what defines “appropriate” technology. A first step in gathering this information is to assess whether current AT provision practices in India have a positive benefit on the lives of consumers. Few data of this type have been collected because of the nascent state of clinical provision in India, though even if provision were commonplace, the data would not necessarily exist. Rehabilitation specialists working to establish quality-care practices and technologies can improve their effectiveness by assessing their current strengths and weaknesses.

The Participant Assessment (PART) questionnaire, used in this study, is an update to the Craig Handicap Assessment and Reporting Technique (CHART). The objective section collects information such as the frequency that the individual does certain activities (such as childrearing and involvement in community religious activities), and the subjective section asks people to rank the importance of and their satisfaction with certain aspects of their life (such as family relationships). The PART is currently being developed. The developers are exploring multiple scoring methods (Marcel Dijkers, personal communication, 15 May 2009).

Wheelchair Skills Test/Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology: wheelchair skills and satisfaction of Indian wheelchair users

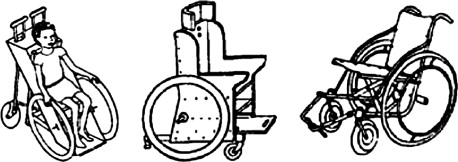

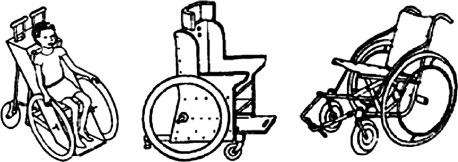

The prescription of customized wheelchairs has become a practice, albeit uncommon, in India in the last 5 to 10 years. Most wheelchairs in India are acquired through vendors or government agencies without clinician input. They tend to be heavy, poorly designed, prone to mechanical failure, and do not allow their users to be independent or to move about efficiently with assistance. Such wheelchairs are often inappropriate for the terrains within India. Many are manufactured locally, but chairs of similarly poor quality are also donated. Because the built environment of India is more challenging to wheelchair users than in Western countries, durability and stability are much more important than some charities and manufacturers realize. In a recent study of Indian home accessibility by Pearlman and colleagues unstable surfaces, narrow doorways, steps, steep ramps, and inaccessible bathrooms were found to be some of the most frequent and challenging obstacles. Several of these correspond with “community” skills described by developers of the Wheelchair Skills Test (WST). Wheelchair skills performance and mobility level have been shown to increase participation, possibly because of individuals’ increased ability to traverse physical barriers within the home and community. Though accessibility in India may be slowly improving, a more immediate impact on participation could come through the provision of wheelchairs that allow the user to exercise better skills. Given the documented failings of poor-quality wheelchairs, the authors hypothesized that individuals would demonstrate better proficiency using clinician-evaluated wheelchairs than they did using hospital-style wheelchairs. In this project, wheelchairs were categorized as either “old/heavy/hospital” (about 50 lb [22 kg], not fitted by a clinician, frequently inappropriate for user) or “active/fitted” (<35 lb [15.5 kg], fitted by a clinician, an educated guess at appropriate technology provision). Pictures of these 2 types of wheelchairs can be seen in Fig. 2 . If results support the hypothesis that custom-fitted wheelchairs provide users with increased independent mobility and technology satisfaction, this will provide evidence in favor of wheelchair distribution models that incorporate fitted chairs.

The WST was developed to fill a need for a standardized wheelchair proficiency instrument in research and rehabilitation. Version 4.1 consists of 32 skills ranging in difficulty from rolling the wheelchair and applying the brakes to ascending stairs. Participants are spotted on all skills. A rater judges whether the participant has passed or failed each skill, and whether failures occur safely or unsafely. It is not possible to pass a skill unsafely. According to the manual, several different percentage scores can be calculated. The Total Performance Score (TPS) measures how many skills out of the total were passed, the Total Attempted Score (TAS) measures how many skills out of the total were attempted, and the Total Safety Score (TSS) measures how many skills out of the total attempted were awarded a safe score. Higher scores indicate more success at completing skills, attempting skills, and safely attempting skills, respectively. Formulas for these calculations can be seen in the Equations. Additionally, the WST can be evaluated in the context of skills that a therapist believes are particularly relevant to an individual participant’s rehabilitation goals.

The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology (QUEST) 2.0 consists of 12 questions that are scored on a scale of 1 to 5, where 5 indicates highest satisfaction. There are 2 principal subsections: device, which contains 8 questions and addresses user satisfaction with the physical properties and utility of the wheelchair; and services, which contains 4 questions and addresses user satisfaction with the sale, information, and maintenance of the wheelchair. In addition, there is a third section that asks users to select from a list the 3 wheelchair characteristics that they consider most important. The contents of the list correspond to topics of questions in the device and satisfaction subsections.

A selection of the literature suggests there are multiple strategies for scoring the QUEST. In a validation of the QUEST with a population of adults with multiple sclerosis, mean subscores for satisfaction with the device and for its services were calculated. Other studies used this technique. Alternatively, several studies calculated the mean score for each individual question (the line-by-line score).

Methods

PART survey

A longitudinal repeated measures survey study was conducted through the analysis of medical records of clients of ISIC who were new recipients of AT. The authors assisted with an ISIC project to assess the quality of its AT provision services, and records from this project were ultimately transferred to the University of Pittsburgh as de-identified existing medical data. Hospital clients were enrolled in the project as they used the DAT’s services (typically wheelchair evaluation), although if they did not have time to complete the measures or were suspected not to understand the questions, they were not included in the transferred dataset.

DAT clients were asked to complete intake forms on demographic data (sex, age, diagnosis/injury level, inpatient/outpatient status, and AT currently owned). Contact information was collected directly into ISIC records as part of the standard hospital intake. Upon completion of these documents, the clients provided responses to questions in the PART questionnaire. Follow-up interviews (repeated PART questionnaires) were conducted by ISIC staff at 6 and 12 months after the baseline. The purpose of these follow-ups was to determine whether community participation and life satisfaction had changed in the year since technology was received from the DAT.

The PART scoring method used involved assigning a numerical value to each response using a scoring key, and then taking a numerical average of the objective and subjective sections. Linear regression was used to evaluate the influence of gender and rural/urban location on responses. Data normality was verified using Q-Q plots of the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month objective and subjective scores. These plots allowed for assessment of data normality with a low sample size. Regression models were built, controlling for gender, semi-urban versus rural (S-R), and urban versus rural (U-R).

WST/QUEST

The WST and QUEST were administered to clients of ISIC receiving new wheelchairs from the DAT. In addition to the client, 3 personnel were involved in each test: an evaluator, a spotter, and a translator (English and Hindi). After the WST was completed, the QUEST survey was conducted. If an individual was unable to respond to a question, it was left blank. The WST and QUEST were administered to clients in their old personal (outpatients) or hospital-provided (inpatients) wheelchair. These measures were then repeated in the new wheelchair. No specific wheelchair training was given to the clients in the interim, although it was provided afterward if a client’s schedule permitted.

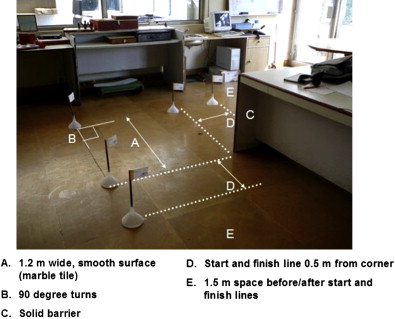

WST evaluation and course setup were conducted as outlined in the WST manual. The obstacle course was set throughout the physiotherapy department, hospital hallways, and on the ISIC grounds. Obstacles such as ramps, cross slopes, and thresholds were identified in existing hospital terrain features. Others (such as steep ramp and pothole) consisted of wheelchair skills training equipment already at the hospital. Some, such as maneuvering paths ( Fig. 3 ), were constructed temporarily using small traffic cones placed on the floor.