Cranial Nerves

Twelve pairs of cranial nerves exit from the brain and brainstem. These nerves innervate the face, head, and neck, controlling all motor and sensory functions in these areas, including vision, hearing, smell, and taste. The cranial nerves may be affected by cranial trauma, infections, aneurysm, stroke, degenerative diseases (multiple sclerosis), upper motor neuron lesions, lower motor neuron lesions, increased intracranial pressure, and abnormal masses or tumors.

An important anatomic feature of cranial nerves is bilateral and unilateral innervation. In bilateral innervation, relatively equal distributions of right and left brain hemisphere innervation govern the function of a specific facial part. Movements that are performed in bilateral synchrony, such as swallowing and moving the forehead, are innervated bilaterally. In unilateral innervation, the contralateral hemisphere innervates the specific body part. Fine movements of the face are examples of unilateral cranial nerve innervation.

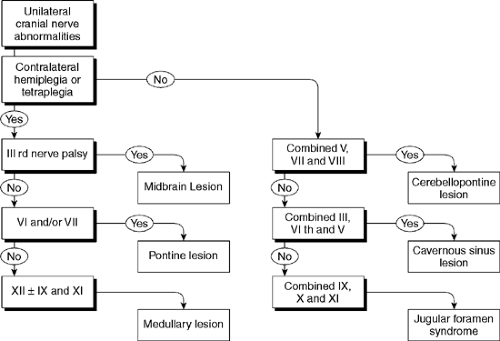

The many types of cranial nerve lesions produce a number of syndromes. Unilaterally affected cranial nerves V, VII, and VIII may indicate a cerebellopontine angle lesion. Unilaterally affected cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI may indicate a cavernous sinuous lesion. Unilaterally affected cranial nerves IX, X, and XI may indicate a jugular foramen syndrome. Bilaterally affected cranial nerves X, XI, and XII may indicate bulbar or pseudobulbar palsy. Multiple cranial nerve abnormalities are shown in Figure 17-1.

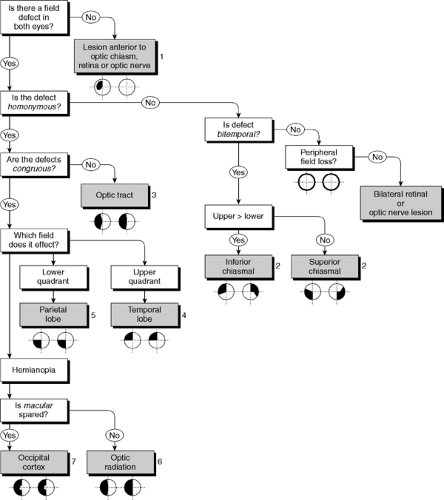

Figure 17-1. Multiple cranial nerve abnormalities. Reprinted with permission from Fuller G. Neurological Examination Made Easy. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1993. |

Procedure

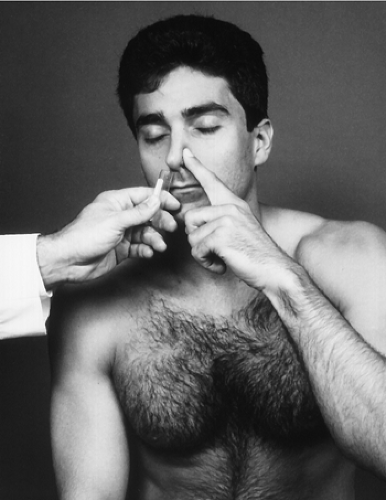

The olfactory nerve is responsible for the sense of smell. To test this nerve, obtain some aromatic substances, such as coffee, tobacco, or peppermint oil. Instruct the patient to close one nostril. Place the substance under the open nostril and ask what the patient smells, if anything (Fig. 17-2). Repeat the procedure for the opposite nostril.

Rationale

If the patient cannot smell or identify the smell unilaterally, suspect a lesion of the olfactory nerve. If the patient cannot smell or identify the smell bilaterally, consider a nonorganic problem or a bilateral cranial nerve I lesion.

Note

A diminished or almost absent sense of smell is common in the elderly. It will be apparent if loss of smell is bilateral and the cranium has undergone no trauma. Other nonneurogenic lesions, such as sinus infection, deviated septum, and lesions caused by smoking, may also cause a loss of smell, either unilaterally or bilaterally.

Procedure

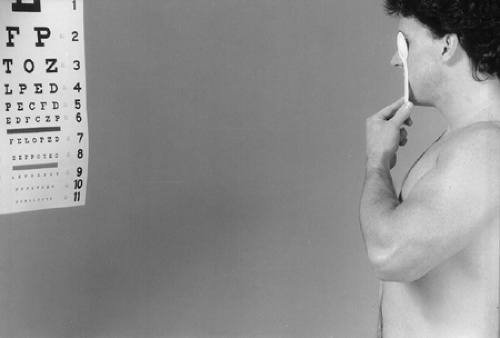

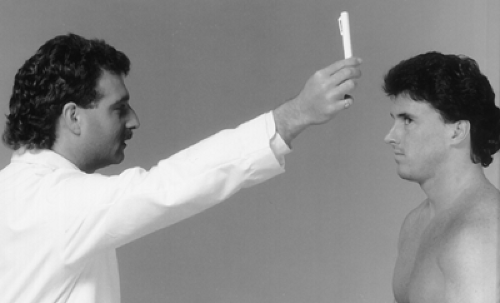

The optic nerve is responsible for visual acuity and peripheral vision. To test for visual acuity, ask the patient to cover one eye and read the smallest print possible on a Snellen chart (Fig. 17-3). Repeat the test with the opposite eye. Note the results. This is not a test for visual acuity for refractive error; it tests the acuity for optic nerve involvement. This test may be performed with the patient wearing glasses or contact lenses.

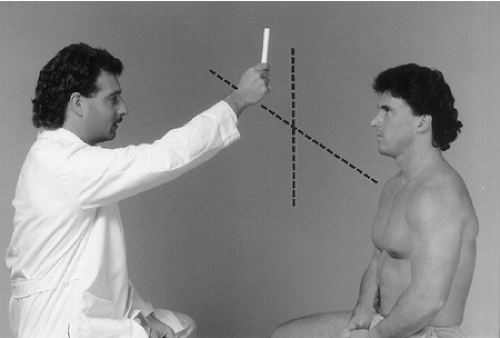

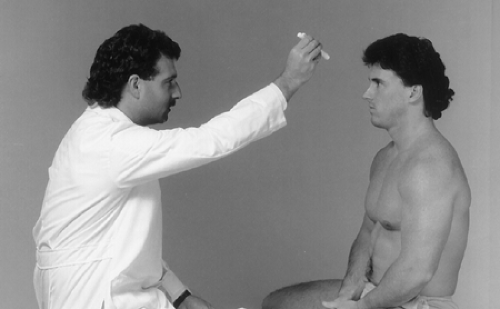

To test for peripheral vision, ask the patient to cover one eye with the hand and keep a fixed gaze on your nose with the uncovered eye. Directly motion a large cross with your finger from superior to inferior and from right to left (Fig. 17-4). Instruct the patient to tell you when he or she begins to see your finger. Repeat with the opposite eye and record the results.

Rationale

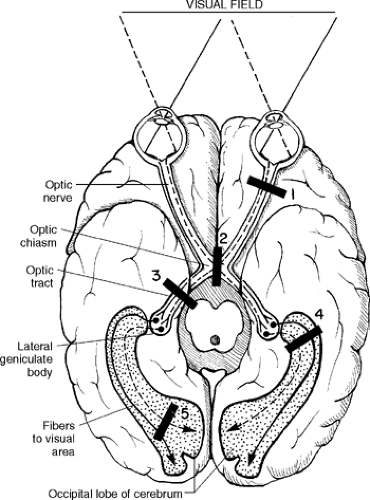

Any loss of vision, from complete unilateral or bilateral loss of vision to loss of half fields of vision (hemianopsia) or a partial defect in the field of vision (scotoma), indicates an optic nerve lesion. Temporal lobe lesions can produce superior contralateral quadrantanopsia. Occipital lobe lesions can produce a contralateral homonymous hemianopsia with macular sparing. Figure 17-5 shows a schematic of the neural pathway from the brain to the retina and demonstrates the location of the lesion and its effect on vision. Also associated with the schematic is a flow chart of field defects (Fig. 17-6).

Procedure

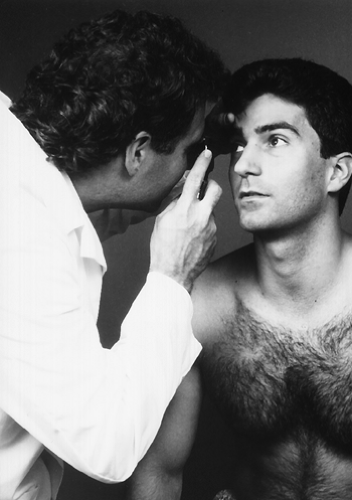

With an ophthalmoscope, look into the patient’s eye. Bring the scope 1 to 2 cm from the eye and encourage the patient to fix the gaze at a distant point (Fig. 17-7). Use the focus ring to correct for your vision and the patient’s vision. If you or the patient is myopic and is not using glasses or contact lenses, turn the focus ring dial counterclockwise to focus on the eye. If you or the patient is presbyopic, turn the focus dial clockwise to focus on the eye. Look at the optic disc, blood vessels, and retinal background.

Rationale

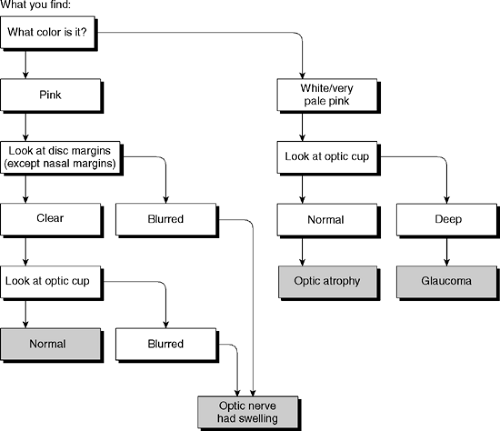

Visualize the optic nerve, the optic disc, and the optic cup for swelling and atrophy (Fig. 17-8).

Figure 17-8. Optic disc abnormalities. Reprinted with permission from Fuller G. Neurological Examination Made Easy. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1993. |

Procedure

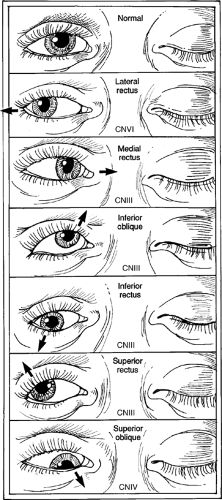

Cranial nerves III, IV, and VI are all associated with ocular and pupillary motility and are tested together for simplicity. Cranial nerve III also innervates the levator palpebrae muscles, which are responsible for movement of the eyelids. First, look at the patient’s eyelids and note any ptosis. After inspection of the eyelids, inspect the eye globes for alignment. Dysfunction of cranial nerve III, IV, or VI may be responsible for deviations of eye alignment. Next, inspect the pupils and determine their size and shape. Then test the pupillary reflex by flashing a light into one of the patient’s eyes (Fig. 17-9). Look at the pupils one at a time for contraction or dilation.

To test ocular movements, have the patient follow either your finger or a moving object through the entire field of vision in all axes. Observe for nystagmus and/or inability to move the eye in a particular axis (Fig. 17-10). Also, test for convergence by having the patient look at a distant object and continue to focus on it as you move that object closer to the patient. The pupil should constrict and converge as the object approaches. Look at both pupils in both instances.

Rationale

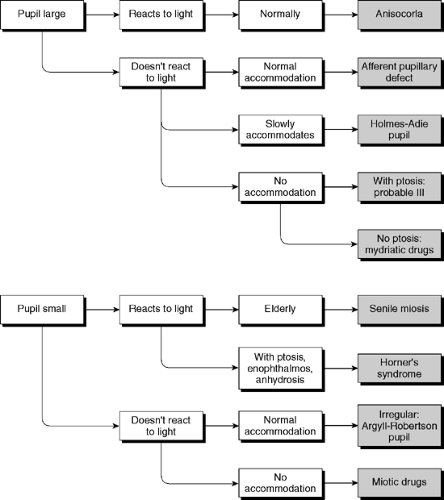

An oculomotor nerve lesion causes ptosis of the eyelid with inability to open the lid. Eye alignment may be down and lateral. Also, the patient will be unable to move the eyeball upward, inward, or downward because of weakness of the medial, superior, and inferior rectus muscles and the inferior oblique muscle. The pupil is usually dilated, and the pupillary reflex is absent. The most frequent cause of a cranial nerve III paralysis is an aneurysm in the circle of Willis. Other conditions may also cause the pupil to dilate and the pupillary reflex to become absent (Fig. 17-11).

A trochlear nerve lesion causes superior and lateral deviation of the eye with inability to move the eyeball downward and inward because of weakness of the superior oblique muscle.

An abducens nerve lesion causes inability to move the eyeball outward because of weakness of the lateral rectus muscle. Figure 17-12 shows lateral rectus muscle defects of alignment.

Figure 17-11. Pupillary abnormalities. Reprinted with permission from Fuller G. Neurological Examination Made Easy. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1993. |

The trigeminal nerve is composed of motor and sensory portions. The motor portion innervates the muscles of mastication. These muscles are the masseter, pterygoid, and temporal muscles. The sensory portion is divided into three branches: the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular branches (V3).

Motor

Procedure for the Masseter, Pterygoid, and Temporalis Muscles

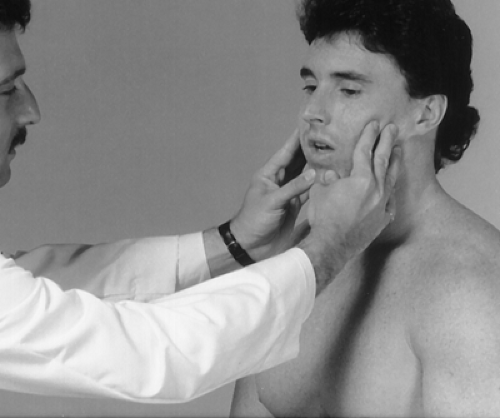

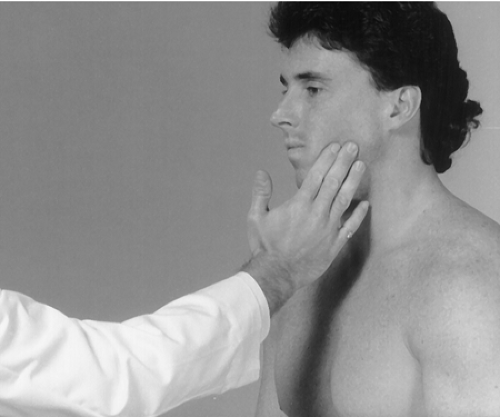

To test the motor portion that innervates the masseter muscle, instruct the patient to simulate a bite while you palpate the masseter muscle and attempt to open the patient’s jaw with your thumbs (Fig. 17-13). To test the pterygoid muscle, instruct the patient to deviate the jaw against your resistance (Fig. 17-14). To test the temporalis muscle, instruct the patient to clench the jaw while you palpate the temporalis muscles with your fingers (Fig. 17-15). Note whether muscle contraction is symmetrical.

Rationale

A weak masseter or pterygoid muscle may indicate a trigeminal nerve lesion. A difference in muscle tension of the temporalis muscle is also an indication of a trigeminal motor lesion. In bilateral paralysis, the jaw may not close tightly. In unilateral lesions, the jaw deviates toward the side of the lesion when the patient opens the mouth.

Figure 17-14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|