2.3 Connective-Tissue Manipulations

Basics

Basics

The pelvis is more than a system of bones, joints, and muscles. Its purpose and function depend on a complex interrelationship between the viscera, the innervating nervous system (sympathetic, parasympathetic, sensory, and motor), the protective skeletal system, and neuromuscular mechanisms.

This complexity means that the clinical reasoning needed when the therapist is faced with a patient’s pelvic problems is both demanding and fascinating. Any examination and regional assessment that only takes into account selective aspects of this anatomical and physiological region may be insufficient. The conceptual approach that underpins connective-tissue manipulation (CTM), and the practical application of the technique, provide a structured approach to the assessment and treatment of the less commonly recognized aspects of pelvic dysfunction. These are the interrelationships between different physiological mechanisms and, particularly, disturbances of autonomic balance. The ways in which these relationships can manifest themselves in symptoms and in which one treatment approach can influence a variety of symptoms is best illustrated through the story of how they were discovered. The story of the origin of CTM provides a fascinating and historical insight.

Elisabeth Dicke was a German physiotherapist who, in the 1930s, was suffering from painful obstructive arterial disease. A leg amputation had become inevitable and she was forced to rest in bed while she awaited surgery. Unsurprisingly, back pain developed, and she found that her hip area, where much of the discomfort was, felt thickened and indurated. When she rubbed the area for relief from pain, she eventually found that a pulling type of manipulation resulted in significant relief, so she asked a colleague to help with this deep tissue therapy. The treatment continued, and as the discomfort eased, surprising additional effects became apparent. The circulation in the affected leg significantly improved and stomach problems were reduced. Having been saved from leg amputation, Dicke spent the rest of her career exploring and developing the technique, and her work was supported and continued by workers such as Kohlrausch and Teirich-Leube (who was working along similar lines at the same time) and was tirelessly promoted by Ilse Schuh and Maria Ebner.

Dicke’s story shows a typical pattern of symptoms and dysfunctions, which appear superficially unrelated but on closer analysis are clearly connected. This analysis offers a challenging alternative approach to complex dysfunctions and symptoms. Dicke approached the discomfort in her lower back from a musculoskeletal perspective as many physical therapists would today, by assuming that immobility and the poor ergonomics of bed rest may lead to low back pain. It would seem logical, then, to treat the condition on the basis of an ergonomic and pain-relieving approach.

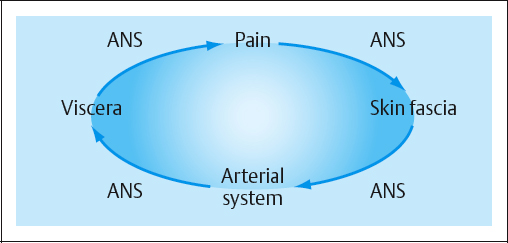

Dicke’s primary problem, however, was arterial. The arterial system is supplied directly by the perivascular nerves, part of the autonomic nervous system [Williams and Bannister 1995]. Disorder in the tissues (in this case, arterial tissues) is reflected in chemical change locally in the tissues and is monitored by the nervous system through antidromic flow of these chemicals (such as bradykinin and prostaglandins) along the axon [Bisby 1982]. These are relayed back to the nerve cell, which responds—having“tasted” the chemical environment of the tissues—by changing its discharge frequency. Other cells in the spinal cord are alerted and input the information into the central nervous system (CNS). Eventually, the synapse transmission threshold may become lowered due to a long-term barrage of noxious stimuli, leading to the synapse becoming “irritated.” The autonomic nervous system (ANS) responds with a heightened state of activity that influences the other tissues and organs it supplies throughout the same spinal segment, and ultimately the whole segment becomes “facilitated” [Korr 1979]. In Dicke’s case, this autonomic “irritation” influenced the circulatory supply to the superficial tissues, which shared the same segmental autonomic nerve supply as the affected arterial tissues. The nutritional state of the connective tissues was affected, resulting in altered fluid balance, thickenings, and indurations, which were apparent on palpation of the lower back/buttock area and produced their own symptoms. The area of affected skin and connective tissue corresponds with the arterial reflex zone identified by Head [1898]. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) also supplies the stomach, and stomach-related symptoms were in evidence. These relationships are clearly seen in each spinal segment. What Dicke demonstrated, therefore, was a dysfunction loop of arterial system, pain, ANS, skin and fascia as well as viscera, which had become a self-perpetuating cycle (Fig. 2.29). The most interesting aspect of this case was that both the primary problem (a lower limb arterial one) and the secondary problem (back pain, stomach and connective tissue) improved with the soft-tissue manipulation. Somehow, the cycle was broken through the addition of an alternative stimulus, which must have impacted on the autonomic system to lower the level of its activity, enabling balance to be restored and function to be improved. This is an attractive theory, which warrants further exploration in order to be sufficiently convincing in today’s scientific and evidence-based health-care culture.

Fig. 2.29 The self-perpetuating dysfunction loop described by Dicke. ANS = Autonomic nervous system.

From a practical perspective, CTM is a manual therapy, but conceptually it is a reflex therapy. It is a manual therapy in that it depends on skilled, careful palpation and the execution of a manual technique that targets connective-tissue interfaces in the skin and fascia. It is a reflex therapy in that its effects are obtained by influencing autonomic cutaneovisceral reflexes. An understanding and assessment of autonomic function and recognition of reflex connective-tissue zones will direct clinical reasoning. CTM appears to be most effective where there is an element of autonomic hypersensitivity.

Connective-tissue manipulation can be defined as: a manual and reflex therapy that targets the superficial connective tissues to stimulate segmental and suprasegmental autonomic cutaneovisceral reflexes in order to restore autonomic balance and reduce dysfunction.

Connective-tissue manipulation can be defined as: a manual and reflex therapy that targets the superficial connective tissues to stimulate segmental and suprasegmental autonomic cutaneovisceral reflexes in order to restore autonomic balance and reduce dysfunction.

When CTM is used to treat visceral disorders such as menstrual problems or segmental pain, treatment via the segmental cutaneovisceral reflexes is an end in itself; however, suprasegmental autonomic reflexes can be influenced to reduce autonomic hypersensitivity or to influence any of the wider functions of the autonomic nervous system.

In relation to CTM, pelvic patients fall into three categories:

- Those with visceral problems, such as menstrual disorders. CTM can be used segmentally to increase circulation to the uterus, reducing congestion and menstrual pain.

- Those with hormonal problems, such as premenstrual syndrome and menopausal symptoms. CTM is used suprasegmentally to enhance autonomic balance and reduce symptoms. Arkarcali and Sener [1994] found that a course of CTM in 19 women resulted in significant improvement in the Blatt menopausal index [Neugarten and Kraines 1965].

- Those with pain, which manifests as musculoskeletal pain but has occurred due to a pelvic visceral “event” such as surgery and is a result of sympathetic irritation through the spinal segment.

Assessment

Assessment

Assessment should follow the approach normally taken by the individual therapist. CTM is most effective where there is autonomic imbalance contributing to symptoms. In patients presenting for physical therapy, this usually accompanies or causes pain and dysfunction that appears to have a musculoskeletal component. CTM “cues” should be watched for, and then subjective assessment should include questions to elicit the extent of autonomic imbalance (Table 2.2). Careful history-taking will show that the pain often does not follow one of the usual dermatomal distributions (for example, it may run down the outside of the thigh and leg) and may worsen during menstruation or bouts of constipation. It may be accompanied by paresthesias such as burning, tingling, or a sensation of something crawling or water running under the skin. The paresthesia is sometimes reproduced when palpating thickened tissues around the sacrum. Alternatively, the pain may appear to be dermatomal, but has not responded to the usual musculoskeletal treatment approaches (such as treatment for nerve root pain). There may be signs of behavioral change relating to autonomic imbalance (such as an inability to sleep and relax) and excess sweating. Detailed questioning may reveal that the balance between fluid input and output is poor (for example, the patient may drink copious amounts of coffee but only empty the bladder twice at work and the patient may have “puffy” ankles). There will sometimes be a “visceral event” that apparently started off the symptoms—the leg pain may have started after a hysterectomy (a symptom the author recognizes as “hysterectomy leg”) or a pelvic or kidney infection.

Pain and paresthesia in a nondermatomal pattern

|

Connective-Tissue Reflex Zones

Connective-Tissue Reflex Zones

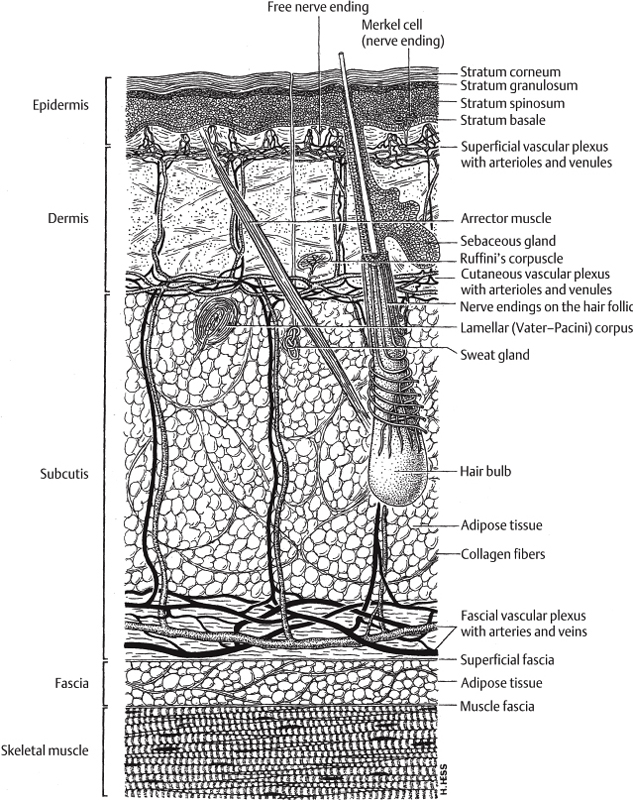

The skin and subcutaneous tissue signal the state of the ANS and are therefore important in assessing ANS dysfunction, indicating which patients may respond well to connective-tissue manipulation. The recognition of connective-tissue zones can be important in assessing patients for treatment [Holey LA 1995a, 1995b, Holey EA 2000], and assessment of these zones should be added to the usual repertoire of objective tests in order to confirm the subjective impression that autonomic imbalance is contributing significantly to the patient’s symptoms (Fig. 2.30). There is some evidence for interrater reliability of recognition of connective-tissue zones [Holey LA and Watson 1995]. The presence and severity of connective-tissue zones should be established. These are changes seen in the superficial tissues and show particularly well on the back. The patient should sit with the back exposed down to the coccyx, with the ankles, knees, and hips flexed to 90° and fully supported. The lumbar spine should be slightly extended, but not hyperextended. This position places the connective tissues under comfortable tension, enabling the zones to be observed. After approximately 30s, when the tissue has settled under the effect of gravity, the tissue changes will become apparent. Indrawn areas surrounded by tissue fluid denote chronically increased tissue tension in the underlying fascia. More acute changes occur between the dermis and hypodermis and tend to show in superficial swellings [Haase 1968].

The body’s connective tissues are composed of a ground substance of glycosaminoglycans (protein molecules that are held under tension by the collagen fibers to offer shock-absorbing properties. These molecules have water-binding properties, and the hydration of the tissues can therefore vary under the influence of hormones and circulatory and sympathetic influences. Disturbances in sympathetic activity can change the molecular hydration and resting tension in the fibers, and on palpation, the tissues may feel “dry” or “puffy,” less elastic and pliable, thickened and indurated, and may be tender when touched.

ANS dysfunction leads to changes in the tissues not unlike those seen in reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD, also known as complex regional pain syndrome, CRPS). These are often very subtle and not easily recognizable without specific training. The skin is superficially edematous. This may not be immediately apparent on visual inspection, but it can be detected using Gunn’s match-stick test—gently pushing a matchstick into the skin leaves a pitting edema on a microscopic level [Gunn 1989]. Pinching the skin produces a peau d’orange (orange-peel) effect in the skin, and gently tapping the skin produces small ripples in the fluid. Touching the skin can create goose pimples, which denote hyperreactivity.

Moving the skin against gravity—pushing superficial layers cephalad against the fascial layer—can reveal underlying tension and an inability of the skin to wrinkle in front of the movement. Thickenings and indurations can be felt due to swelling in the tissue [Michalsen and Buhring 1993].

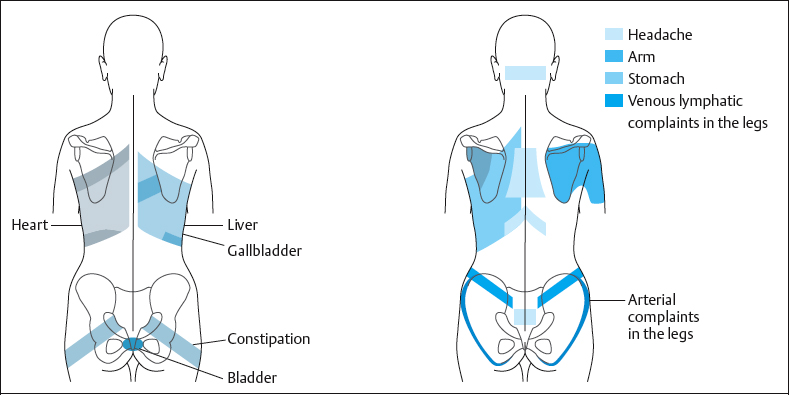

The reflex changes are visible and palpable, and occur in skin zones that share a segmental relationship with the affected viscera. These are termed Head’s zones, after the British neurologist Sir Henry Head, who first identified them in 1898, and are sometimes now called connective-tissue reflex zones (Fig. 2.31). Although a number of reflex therapies use reflex areas, these are the only reflex zones that can be visually recognized, palpated, and understood anatomically [Holey EA 2000]. These zones can indicate the degree to which ANS dysfunction occurs; chronic changes in the zones indicate a more long-standing problem, widespread zonal changes indicate a more generalized autonomic imbalance. An example of this is when a bowel zone is present due to an ulcerative bowel condition. The liver and stomach zones may indicate long-term effects of drug therapy. Central zones may suggest general autonomic imbalance and relate to headaches. Which of the zones relate to the primary or secondary problems is established through the medical history. Occasionally, a “silent zone” may be present—a zone that is clearly seen and palpated but does not match any current symptoms [Ebner 1985]. Usually, this denotes a genetic predisposition to a problem; there is likely to be a silent heart zone in someone who has a family history of heart problems, for example. These silent zones present the therapist with a clinical and ethical dilemma, and the decision on whether it is appropriate to discuss these tissue changes with the patient has to be made on an individual basis.

Technique

Technique

The strongest effect is produced by Dicke’s fascial technique [Dicke 1978], which works best when performed with the middle finger of either hand (as it is the longest) or the thumb tips. Flexion at the distal interphalangeal joint gathers up the slack in the skin, and overpressure gently exerted at the end-feel then creates a shear force at the skin–fascial interface [Holey LA 1995a]. When the technique is applied correctly, a distinctive “cutting” sensation is produced. Teirich-Leube, however, found that a gentler flat or shallow technique, which does not produce the cutting sensation, is often sufficient to produce the desired effects [Schuh 1992]. In any case, it is a useful preparatory technique for reducing swelling and tension in the skin. Preparatory strokes can be used to desensitize very tender tissues (subcutaneous technique), or to enhance the response to the fascial technique (skin technique), or to reduce superficial swelling and tension to enable the fascial technique to be used (flat technique) [Holey EA and Cook 1997]. The flat technique often produces a sufficient response, so that the fascial technique becomes unnecessary [Schuh 1992].

It is important that the correct tissue interface should be targeted, or adverse reactions and paresthesia can result, which can last for a number of hours and be very uncomfortable.

Indications

Indications

Connective-tissue manipulation is useful in treating:

- Pain, particularly chronic pain with sympathetic involvement.

- Nerve root pain.

- Pain that does not follow the classic dermatomal distribution patterns.

- Symptoms of stiffness (for example, in degenerative joint disease).

- Autonomic imbalances:

- – Sympathetic dominance (symptoms include: feeling “speedy,” being unable to relax or sleep, feeling tense, irritable, having increased bowel or digestive function, anxiety).

- – Parasympathetic dominance (symptoms include a lack of energy, a tendency to sleep excessively, sluggishness, reduced bowel or digestive function, low mood).

- – Sympathetic dominance (symptoms include: feeling “speedy,” being unable to relax or sleep, feeling tense, irritable, having increased bowel or digestive function, anxiety).

- Fluid imbalance (chronic swelling, tissue congestion, compartment syndromes).

- Autonomic/circulatory dysfunction.

- Hormonal imbalance (menopause symptoms, menstrual irregularities or pain).

- Visceral dysfunction (e. g., digestive, constipation, menstrual).

CTM is strongly indicated when several of these problems coexist, although it can be effective where the problems occur in isolation. Some evidence has been provided through a number of small studies. Akbayrak et al. [2001] found that migraine symptoms in 30 female patients improved by using hot packs, massage, and CTM. Citak et al. [2001] demonstrated that CTM reduced general pain intensity, sleep disturbance, and connective-tissue tenderness in 20 female subjects with primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Holey EA and Lawler [1995] found that CTM was more effective than abdominal massage in improving bowel function in a controlled experimental single-case study. Horstkotte et al. [1967] found that in terms of peripheral blood flow, the delayed effect of CTM produced an increase that was superior to that produced by the drug therapy of the day. It is used to good effect in intermittent claudication. Frazer [1978] found that it was as powerful as epidural anesthesia in a single patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree