several late consequences of this disorder and felt that the condition was an exaggerated inflammatory response rather than sympathetic overactivity (35,36 and 37). DeTakats in 1937 described a condition called reflex dystrophy involving pain with vasomotor disturbances, trophic changes, and relief of pain with sympathetic blocks (38). Evans in 1947 reviewed a large series of cases and described a similar series as RSD (39). Unfortunately, while this entity has become the most widely described posttraumatic pain syndrome to date, its clinical description has lacked refinement since its inception.

TABLE 68.1 Historical Synonyms for CRPSs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 68.2 CRPS-Diagnostic Criteria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 68.3 Drawing depicting appearance of various nociceptors and mechanicoreceptors found in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. |

disruption. Contrasting opinions also exist, even back in the early 1900s; Sudeck thought that causalgia was an exaggerated inflammatory response rather than an overactive sympathetic system (36). Since sympathectomy for hypertension did not alter the sensitivity of an extremity (18), it was postulated that normal sympathetic activity could stimulate pain signals along afferent sensory fibers at the site of the nerve lesion (40). This line of thinking was further advanced by authors proposing a complex chain of events peripherally and centrally occurring without specific sympathetic overactivity (52,53,61,62 and 63).

there is a coupling mechanism that permits sympathetic control of depolarization of myelinated Aδ and unmyelinated C afferents in the periphery (42,53). There are several theories in which this coupling effect can take place, and many of these have been tested in human investigations and animal models (91,92,93 and 94). These include direct chemical coupling, indirect coupling, and ephaptic coupling. The direct chemical coupling seems to have the most support and also explains why lumbar sympathetic blocks and peripheral sympathetic blocks all can relieve pain. The coupling effect theory is further strengthened by profound histologic changes seen of affecting small diameter sensory afferents in amputated limbs from CRPS patients (95).

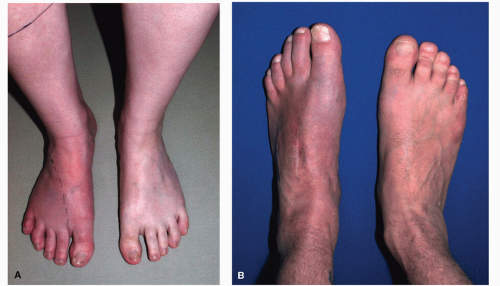

and posteriorly (14,116). The pain described typically is more severe than anticipated from the injury. Over time, the pain will tend to spread if untreated and include a component of mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity.

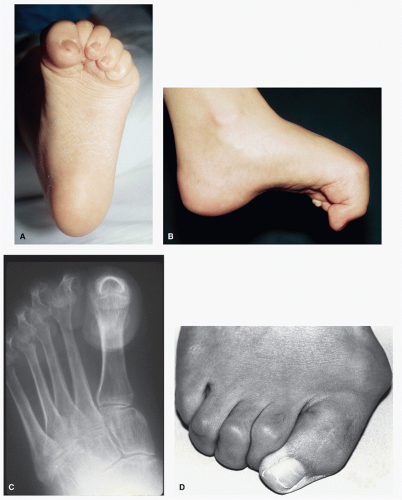

Veldman et al, in a large prospective series of 829 patients suffering from CRPS, found tremor and muscle incoordination in approximately 50% of the patients (105). A perceptible lag time can be seen between asking a patient to move the injured part and the first observed movement (98). Often a quivering in the digits with paradoxical contracture of opposing muscle groups is observed (i.e., extensors firing when digits are being flexed). With careful questioning, patients with CRPS will often relate problems with movement. They may say something like “my brain is telling it to move, but it won’t”; however, with milder expressions, movement disorders may be less apparent. Carefully observed clinical motor testing will reveal these subtle movement deficit (see “Physical Examination” section). Bilateral motor impairment (“mirror image” distribution) has also been reported (98).

to their injury, never had any documented psychological issues (109). Like any chronic pain, CRPS can shape behavior that can lead to pathologic emotions. Just the anticipation of pain without experiencing the stimulus can trigger the behavior. This learned pattern of operant reaction to painful experiences will reinforce a decay of activity and advance of pain avoidance (133). All CRPS patients suffer from this phenomenon in varying degrees; however, patients with magnified psychological responses will be inherently more difficult to treat. While some patients have psychological problems that can complicate their care, in over 90% of the cases, these are the consequence of CRPS and not the cause of their disability (6).

in 70% (19 patients) to a distant location from the initial site. Mirror image spread was noted in four patients (15%) (137).

TABLE 68.3 Known Precipitating Factors of CRPS in Extremities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

most common with mononeuropathy. Unfortunately, he cited their own group’s work to build their case and did not offer any psychiatric evidence to support their findings.

if possible. In many published investigations, expensive testing equipment is used to accurately collect quantitative data. While these devices are most accurate, their use can be very time consuming, and therefore, routine use may be limited. The most effective tests in the clinical setting are semiquantitative and qualitative tests that are simple, reproducible, and relate directly to underlying pathophysiologic pain mechanisms (201). Once such sensory aberrances are defined, tailored treatment plans to combat these pathologic mechanisms can be devised.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree