Chapter 19 Complement Deficiencies in Human Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and SLE Nephritis: Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

INTRODUCTION

The involvement of complement in the etiopathogenesis of SLE was revealed when the introduction of routine measurements of the hemolytic complement activities (CH50) and component protein levels (mainly C3 and C4) showed that serum complement protein levels are usually decreased in patients with SLE. However, complement abnormalities were not included in the 1997 revised criteria of the American College of Rheumatology for the diagnosis and classification of SLE, although they are among the most powerful markers for SLE disease susceptibility and disease activity.1

SLE is a complex disease that involves multiple genetic and environmental risk factors that initiate the disease.2,3 It is thought that each of numerous susceptibility genes contributes modestly to an increased risk of SLE in a subject. However, in a small subset of patients a homozygous single-gene defect can be the major driving force for disease onset. A total deficiency in one of the early components of the classical complement activation pathway represents such a single genetic factor that strongly predisposes a subject to SLE.

CHARACTERISTICS OF SLE ASSOCIATED WITH COMPLEMENT DEFICIENCY

The earliest indication suggesting that human subjects with complement deficiencies are predisposed to immunopathogenic diseases came from reports in 1971 to 1974. In many cases of SLE, lupus-like syndromes, or glomerulonephritis patients were found to have genetic deficiencies of C1q, C1r, C1s, C4, C2, or C1-inhibitor (Table 19.1). At present such deficiencies are the strongest disease susceptibility genes for the development of human SLE.4,5

TABLE 19.1 SLE AND OTHER SYMPTOMS IN TOTAL DEFICIENCIES OF COMPLEMENT COMPONENTS OF THE CLASSICAL PATHWAY OF ACTIVATION*

| Components | Number of Cases | SLE and Other Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|

| C1q | 42 | SLE (30); GN (16); CNS disease (7); recurrent bacterial infections (13); with septicemia in early childhood (4); moniliasis (9) |

| C1r, C1s | 14 | Lupus-like syndrome (4); SLE (2) DLE (2); GN (2); infections (8); otitis media, gonococcal infection, tuberculosis, post-varicella encephalitis, virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome |

| C4 | 28 | SLE (17); SLE-like disease (5) GN (6); infections (7); dead (4); healthy (1) |

| C2 | >150 | SLE & SLE-like disease (34%); increased susceptibility to infections (25–30%); glomerulonephritis (∼10%); cardiovascular disease (∼15%) |

CNS, central nervous system; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; GN, glomerulonephritis.

* Number of cases in parenthesis.

It appears that the association of complement deficiency with SLE shows a hierarchy of prevalence and disease severity according to the position of the protein in the activation pathway.6 The highest frequency and the most severe disease is associated with a deficiency in one of the proteins of the C1 complex (C1q, C1r, and C1s) or with a total deficiency of complement C4 (i.e., C4A and C4B). Seventy-five to 90% of human subjects with a homozygous deficiency of C1 or C4 have SLE or lupus-like disease. Remarkably, the intra-familial disease concordance rate for SLE in combination with C1 or C4 deficiency even exceeds that observed between siblings of monozygotic twins (24 to 69%).

The disease associated with hereditary complement deficiency tends to be of early onset, and (unlike the high female preponderance among the majority of SLE patients) the female-to-male ratio is approximately 1:1.7 By contrast, complement C2 deficiency (C2D) is associated with a lower prevalence of disease (estimated at approximately 10%) and a disease onset similar to regular SLE patients with a female predominance.8 In addition to a tendency to develop SLE, individuals with a homozygous deficiency of C1q/C1r/C1s, C4, or C2 often have a higher susceptibility to recurrent or invasive bacterial infections.

DEFICIENCIES OF SUBCOMPONENT PROTEINS FOR THE C1 COMPLEX

C1q Deficiency

The human A, B, and C genes of C1Q are closely linked on chromosome 1p34 through 1p36. Hereditary C1q deficiency is caused either by a failure to synthesize C1q (∼60% of cases) or by the synthesis of a nonfunctional low-molecular-weight (LMW) C1q (∼40%). Coding mutations have been identified that lead to the formation of a premature termination codon at amino acid residues 6 or 41, or frame-shift mutations from codon 43 together with a stop codon at residue 108 of the C-chain, a stop codon at residue 150 of the B-chain, and a stop codon at residue 186 of the A-chain.9–11

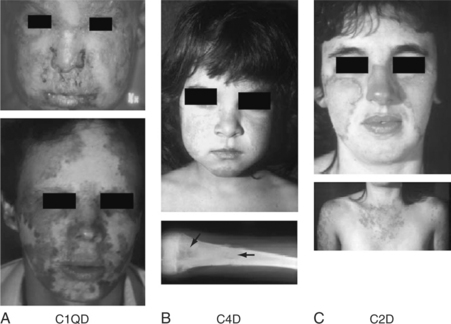

The vast majority of known human subjects with homozygous C1q deficiency (39 of 42, 93%) have developed a clinical syndrome related to SLE (Fig. 19.1) with skin rash (36 subjects, 86%), glomerulonephritis (GN; 16 subjects, 38%), and central nervous system (CNS) involvement (7 subjects, 17%). The disease is present equally in males and females and is typically of early onset, with a median age of 6 years (range: 6 months to 42 years). The prevalence of autoantibodies is slightly lower than that of regular SLE patients: ANA 24/34 (70.6%), ENA (extractable nuclear antigens Sm, RNP, Ro and/or La) 15/24 (62.5%), and anti-dsDNA 5/24 (20.8%). At least one-third of the C1q-deficient patients also suffered from recurrent bacterial infections, including otitis media, meningitides, and pneumonia. Four C1q-deficient patients died with septicemia in early childhood. Some patients developed diffuse monilia and aphtous lesions in the mouth and toenail deformity secondary to moniliasis9 (panel A, Fig. 19.1).

Low Levels of C1q Proteins

In addition to coding mutations reported in patients with complete deficiency of C1q, a silent single-nucleotide polymorphism at codon 70 (GGG—>GGA) of the C1QA gene was found to be associated with decreased levels of C1q in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE).10 The cause for such a reduced level of C1q is not known.

Hereditary C1q deficiencies should be distinguished from acquired C1q hypocomplementemia in SLE patients or other autoimmune conditions, including hypocomplementary urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS), cryoglobulinemia, and severe combined immunodeficiency syndromes. These are due to an increased protein consumption, especially under conditions related to the presence of autoantibodies against C1q. C1q autoantibodies are present in approximately one-third of SLE patients, who often have renal disease and higher clinical disease activities. 9,12,13

C1r and C1s Deficiencies

The genes for C1r and C1s are in close linkage on chromosome 12p13. Typically, those individuals who have no C1r protein may also have reduced levels of C1s (∼20 to 40% of normal level).7 Deficiencies of C1r and C1s have been reported in 14 cases so far. Among them, 12 developed a lupus-like disease with skin rash, discoid lupus, or SLE. A majority of patients presented also had severe bacterial or viral infections. The female-to-male ratio was 1.7:1. Relatively lower prevalence of ANA (62.5%) was found. Molecular defects leading to C1s deficiency had been studied in three patients. Among them were two nonsense mutations in exon 12 at codon 53414 or codon 60815 and a 4-bp deletion in exon 10 that created frameshift mutations and formation of a premature stop codon.15,16 The molecular basis of C1r deficiency has not been determined.

TOTAL AND ISOTYPE DEFICIENCIES OF COMPLEMENT COMPONENT C4

Total Deficiencies of C4A and C4B

A remarkable feature of human complement C4 genetics is the variation in the gene copy number and gene size. One to five copies of long (21 kb) or short (14.6 kb) C4 genes can be present at the central region of the MHC on chromosome 6p21.3.17 To date, 2 to 7 copies of C4 genes in a diploid genome have been demonstrated to be frequently present among different healthy subjects. Each of those C4 genes may code for an acidic C4A protein or a basic C4B protein. The high copy number of C4 genes probably evolved to increase the diversity and reduce the possibility of a total deficiency of C4A and C4B proteins in an individual.

To date, 28 individuals from 19 families with a complete deficiency of both C4A and C4B proteins have been firmly established.4,18,19 Among these C4D subjects, 17 were diagnosed with SLE according to the ACR criteria. Of the remaining 11 subjects, 5 had lupus-like disorders such as photosensitive skin lesions and/or discoid lupus and 6 had kidney disease such as mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, recurrent hematuria, membranous nephropathy, and Henoch-Schöenlein purpura with end-stage kidney failure. Repeated and invasive (and sometimes fatal) infections were reported in at least 7 individuals (bacterial meningitidis, osteomyelitis, otitis media, respiratory tract infections, and septicemia). Only one subject, age 21 at the time of report, remained relatively healthy. The age of SLE disease onset/diagnosis among C4D subjects varied from 2 to 41 years. The female-to-male ratio of affected patients was close to 1:1 (13 female/14 male). Four C4D patients died between 2 and 25 years of age.

Common clinical manifestations of C4D are photosensitivity, severe skin lesions (sometimes with scarring atrophic lesions on the face and extremities), Raynaud’s phenomenon, infections, and renal disease (panel B, Fig. 19.1). Serologically, antinuclear antibodies are generally present at low titers or absent. Of special interests is the frequent presence of anti-Ro/SSA but the absence of anti-La/SSB antibodies. Anti-dsDNA antibody tests were negative in 9 of 11 patients studied.4,7,19

The molecular basis of total C4 deficiencies was elucidated in 12 Caucasian subjects with six different HLA haplotypes. The common cause of total C4 deficiency is due to the absence of a C4B gene and the presence of a single long C4A mutant gene in an MHC haplotype that has a mini-insertion or deletion (indel). There are also MHC haplotypes with two nonfunctional C4 genes in tandem. The most prevalent molecular defect leading to nonexpression of a C4 protein is a 2-bp insertion at codon 1213 in exon 29.20 Other deleterious mutations include G—A mutation at the donor site of intron 28 (of C4B), a 1-bp deletion at codon 497 (of C4B) or a 2-bp deletion at codon 522 (of C4A) in exon 13, and a 1-bp deletion at codon 811 of exon 20 (of C4A).18

C4A and C4B Isotype Deficiencies

Gene copy number and gene size variations are the two major factors contributing to the quantitative diversity of complement C4 plasma protein levels among different individuals.21 They create a wide range of plasma protein levels for each isotype, including a homozygous lack of C4A or C4B. The initial observations in the early 1980s of an association between homozygous deficiency and partial deficiency of C4A (i.e., substantially lower expression level of C4A than C4B in a subject) and SLE22 have since been replicated and extended. Cumulative results from more than 35 different studies revealed that homozygous C4A deficiency is increased from less than 1% in the healthy populations to 3.5 to 5% in SLE patient cohorts, whereas partial or heterozygous deficiency of C4A increased from 21.7 to 24% in the healthy controls to 40.2 to 42.9% in SLE patient populations. Those study populations included Northern and Central Europeans, Anglo-Saxons, Caucasians in the United States, and East Asians. French SLE patients and controls showed relatively lower frequencies of C4AQ0, but the differences between the patient and control groups were statistically significant.18

The clinical manifestations associated with homozygous C4A deficiency have been reported in several studies. In a cohort of 80 Swedish SLE patients, there were 13 homozygous C4A-deficient subjects, who had an increased incidence of photosensitivity but other clinical features were similar to non C4A-deficient individuals. No differences were seen in the percentage of anti-dsDNA, Sm, RNP, Ro/SS-A, La/SS-B, rheumatoid factors, or anticardiolipin antibodies for these patients. In North American studies of Caucasian SLE, homozygous C4A-deficient patients were found to have a higher incidence of cutaneous disease but in general a milder disease course with lower incidence of renal involvement and proteinuria, lower incidence of seizures, and less common anti-dsDNA, anti-SM, anti-Ro, and anticardiolipin antibodies.23–25 On the contrary, East Asian SLE patients with homozygous C4A deficiency were associated with more severe disease activities (including higher incidence of renal disease and serositis and higher titers of anti-dsDNA) when compared with SLE patients without a homozygous C4A deficiency.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree