7 Communication

getting it right

Introduction

The specific types of communication problems that frequently occur as a direct result of stroke include aphasia and dysarthria. Communication disability persisting after stroke is relatively common and unfortunately the impact of this disability often stretches much further than may be expected because stroke survivors with communication difficulties experience low self-esteem, loss of social confidence and feelings of stigmatisation (Dickson et al. 2008). Overcoming the challenges that communication disability brings requires an awareness of the complexities of communication, the influence of the environment and a willingness to engage in a partnership with the individual to overcome some of the hurdles.

The environment has a strong influence on communication (Howe et al. 2008). This includes both the physical environment with its space and acoustics, and the social environment. The social environment refers to the opportunity to communicate prior to, during and following exercise sessions. The expectations, beliefs and values of both the exercise professional and the stroke survivor will influence the social environment. Good communication is therefore important to facilitate a shared understanding of the potential benefits and barriers of engaging in the exercise programme, and to agree with the stroke survivor the goals, content and processes of the exercise programme.

Demonstrating Effective Communication Skills

How do we Communicate?

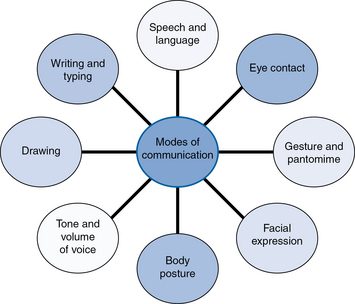

Communication can be both verbal and non-verbal. The expressions ‘It’s not what she said, it’s the way she said it’ or ‘Actions speak louder than words’ demonstrate this. The term non-verbal communication could be interpreted as any form of communication not involving spoken or written words; however, this is not strictly true as non-verbal messages often accompany verbal expression (Hargie and Dickson 2004).

Non-verbal communication can serve several purposes; it can:

• Completely replace speech, e.g. where the chosen method to communicate is sign language or a simple signal or gesture across a busy room.

• Complement speech by emphasising some aspects of the message, e.g. showing emotion and pointing and gesturing to clarify points.

• Contradict the spoken word, e.g. body language that suggests another message. These non-verbal behaviours can be deliberate such as when using sarcasm or humour. However, behaviours can also be outwith personal control, e.g. blushing or tensing, and therefore revealing the true message.

• Control the initiation and turn taking in conversation, e.g. eye contact acts as a signal for when to listen and when to talk.

Utilising all the available modes of communication (Fig. 7.1) and being aware of one’s own non-verbal communication is important when establishing effective working relationships with stroke survivors.

Using Active Listening

Active listening involves the following:

• Considering what the person is actually meaning by attending to the words, body language and tone of voice to extract the real message.

• Considering the full implication of the information, e.g. is it expected or unusual?

• Using and providing feedback as the communication progresses, i.e.:

Health-care professionals are likely to receive training to understand the components and benefits of their communication practices (Parry and Brown 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree