Clubfoot

Luke D. Cicchinelli

David J. Granger

Todd R. Gunzy

Todd B. Haddon

Jorge G. Penagos Vasquez

Pediatric and neglected clubfoot surgery requires every ounce of focus, concentration, and clinical experience a surgical team can offer. Each case is a unique challenge, and although principles of management exist, the results are proportionate to surgeon and assistant’s ability, postoperative management, as well as patient and parental compliance.

Textbook chapters and journal articles abound detailing a global experience with the management of talipes equinovarus. The written literature underscores exhaustively the very challenge of surgical management in that there is such variability in factors such as patient age, rigidity, previous surgery, and economic means or support that every case is essentially an N = 1. These factors all directly affect the outcome.

This chapter blends in detail the pertinent intraoperative anatomy with the authors’ clinical experience gleaned over the last 20 years in many different countries. We believe an efficient, focused surgical game plan that proceeds in an orderly fashion yet with enough flexibility to adjust to intraoperative findings and events is critical. J. Leonard Goldner’s four-quadrant approach and categorization to surgical management of clubfoot is an unfailing reference that every surgeon is advised to consider and reconsider prior to operating—each and every time, each and every case.

The medial, posterior, and lateral quadrants are illustrated via two case study dissections with all author experience and commentary included within the legends for facilitation of immediate visual link with the written word. The inferior quadrant is not illustrated but is mentioned, as it is essentially a Steindler and intrinsic release from the calcaneus. Access to the inferior or plantar quadrant is discussed within the dissection of the medial quadrant.

Our intent is that this work serves as a detailed conversation between an experienced clubfoot surgeon and a novice clubfoot surgeon or resident as first assistant during the surgical exposure and event. This is a luxury unfortunately not often possible in the operating room due to case loads and the importance of expedition and fluidity when treating pediatric patients. The reader, in the role of the first assistant, is implored to focus, concentrate, study, and visually and mentally dissect and digest the text and photos in tandem. Prior intensive and extensive study of available literature and published chapters on clubfoot surgery when combined with these clinical cases will bring the reader as close as possible to actually being scrubbed in and assisting on an actual case.

The experienced clubfoot surgeon reading this chapter is asked to consider it a conversation between colleagues with similar interests and that any common or divergent experiences be the stimulus for future dialogue and passed on to younger surgeons and residents. There simply is not much room for on-the-job training in pediatric clubfoot surgery. In spite of the plethora of world literature and study, it is surgeon experience, patience, focus, and ability that create the results.

TECHNIQUE

Almost exclusively, every clubfoot that has failed nonoperative management requires a posterior and medial release, as illustrated in case 1 (Figs. 74.1,74.2,74.3,74.4,74.5,74.6,74.7,74.8,74.9,74.10,74.11,74.12,74.13,74.14,74.15,74.16,74.17,74.18,74.19,74.20,74.21,74.22 and 74.23). The lateral and plantar quadrants are required on a case-specific basis based on intraoperative assessment and patient-specific factors such as rigidity, previous surgery, and patient age. It has been our distinct experience that full releases and articular realignment attempts in neglected clubfoot surgery fail in older children or give equal to less gratifying results as talectomy while causing more surgical trauma. A talectomy with a posterior and medial release when indicated and a lateral column calcaneal cuboid wedge arthrodesis are the most efficacious ways to improve function once a patient has reached 8 years.

Case 2 illustrates a talectomy and also allows commentary on the lateral quadrant with additional discussion of the posterior quadrant and an abductor release (Figs. 74.24,74.25,74.26,74.27,74.28,74.29,74.30,74.31,74.32 and 74.33).

We believe this chapter will benefit surgeons of all skill levels to provide them a general introduction, improve their technique, or present a new “tip” in their treatment algorithm. Just as important is the understanding of biomechanical concepts of clubfoot kinematics and the advent of Ponseti casting techniques. Diligent research into the movements and adaptations that occur in the clubbed foot will impart a greater understanding to the rational of our current approach. Likewise, understanding the principles and utility of casting is imperative. With success rates approaching 100% and long-term outcome studies heavily favoring casting, it would be a disservice not to attempt casting in every patient, whether it be an untreated clubfoot or a failed surgical outcome up to 4 years of age. While it would appear that the understanding of good surgical technique becomes superfluous due to a dramatic decrease in utilization, casting failures and revision cases will be the most challenging due to the increased stiffness of the foot. Most casting failures are “atypical” clubfeet with a significant cavus component of their deformity; therefore, it is crucial in these cases to have a thorough understanding of the structures that need to be released to have a favorable outcome.

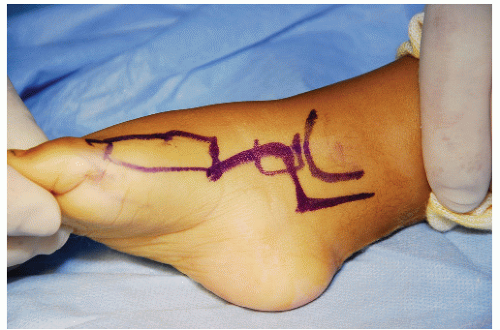

To review our stepwise approach, the presented skin incision is placed as such to gain access to all necessary ligamentous structures, while understanding that scar contracture is likely to produce recurrence of the deformity. The Cincinnati incision, while still in use today, has fallen out of favor due to an unnecessarily large exposure and a high rate of scar contracture. With this incision, it is sometimes necessary to perform a tandem fasciocutaneous flap, which only complicates scarring. We use a modified Turco incision to gain access only to the structures that cannot be accessed from the lateral incision.

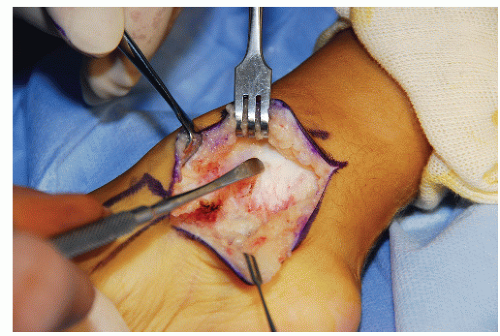

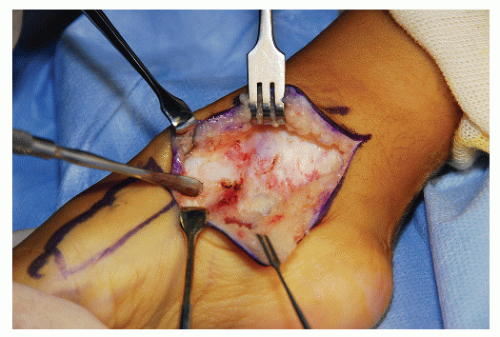

Figure 74.3 Distal exposure is completed when the anterior tibialis tendon is identified dorsally (between the dorsal Ragnel and Freer elevator) and inferiorly where the abductor muscle can be seen just above the double skin hook. The insertion of anterior tibial tendon confirms the location of the first metatarsal-cuneiform joint, which may be important later if medial capsulotomies are required for forefoot adductus release. It is an error to continue exposing superficial to the abductor muscle as no work will be performed there. Dissection deep to the abductor exposes the planter vault and specifically gives access to the master knot of Henry, which links the FHL and FDL tendons. The tip of the Freer indicates the undersurface of the medial cuneiform or entrance to the plantar vault.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|