Closed Reduction and Pinning of Supracondylar Humerus Fractures

Jenna M. Godfrey

David L. Skaggs

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

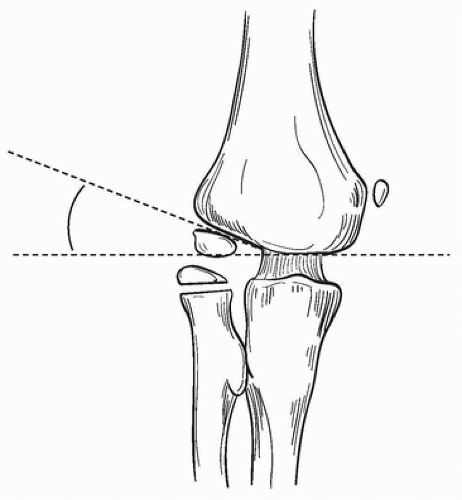

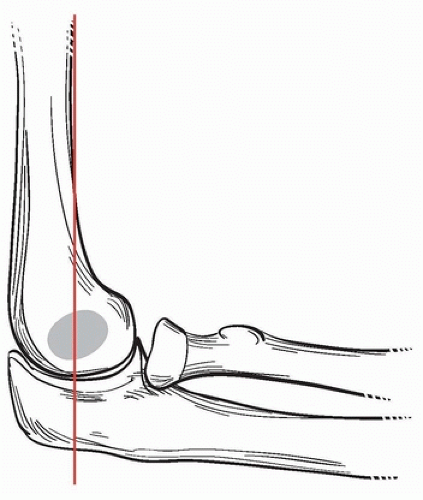

As the operative treatment of supracondylar fractures with reduction and pinning is so effective and safe, the great majority of displaced fractures can be treated operatively. There is little controversy that all closed Gartland type III and IV fractures should be treated with operative reduction and pinning (1, 2, 3). In fractures that are not clearly displaced, three criteria are helpful in determining if the fracture should be treated operatively (1). On a lateral view of the elbow, the anterior humeral line should intersect the capitellum (Fig. 1-1). It does not necessarily need to bisect the capitellum, but it should at least touch it. Initial attempts at a lateral x-ray may be of poor quality and need to be repeated (2). Baumann angle should be at least 11 degrees (Fig. 1-2) or similar to the contralateral side (3). Beware of fractures in which the medial column is comminuted, which is usually associated with a loss of Baumann angle, and an indication for pinning (Fig. 1-3).

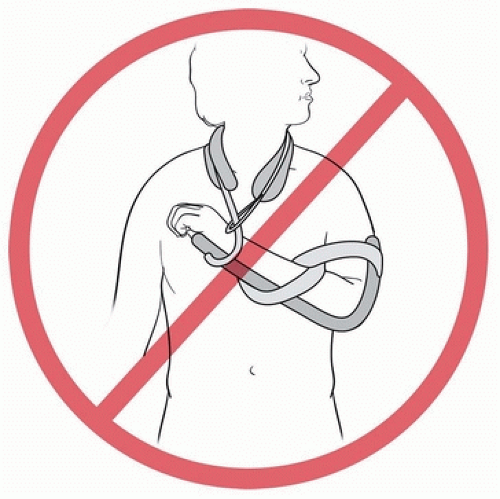

Controversy exists as to how much displacement warrants operative reduction (4, 5). In the past, type II fractures have been treated with closed reduction and casting in hyperflexion to maintain the reduction. Studies have shown that in children with supracondylar fractures, as elbow flexion increases, the compartment pressure of the forearm increases and the brachial artery flow decreases, creating an environment ripe for a compartment syndrome (6, 7). As contemporary case series have such good results for the closed reduction and pinning of type II fractures (4), we believe it is safer

to hold a type II fracture reduced with pins, rather than in a cast with the elbow flexed greater than 90 degrees (Fig. 1-4). The 2011 AAOS Guidelines for the treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures also recommend pin fixation for type II fractures (3).

to hold a type II fracture reduced with pins, rather than in a cast with the elbow flexed greater than 90 degrees (Fig. 1-4). The 2011 AAOS Guidelines for the treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures also recommend pin fixation for type II fractures (3).

FIGURE 1-1 On a lateral view of the elbow, the anterior humeral line should intersect the capitellum. |

There is little growth and remodeling about the elbow (8). Accepting a fracture position in which the capitellum is posterior to the anterior humeral line on the lateral view does not predictably remodel, and the child is likely to end up with a permanent loss of elbow flexion. In young children (aged 3 years and under), where the anterior capitellum just touches the anterior humeral line, casting in situ may be considered. In general, our indications for operative reduction and percutaneous pinning of supracondylar humerus fractures in children are all closed, acute, and displaced (type II, III, and IV) fractures (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

FIGURE 1-3 Look for medial comminution, which is indicative of the fracture being in varus, and usually requires operative reduction and pinning. |

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The most important part of preoperative planning is assessment of the soft tissues. A good rule of thumb is to assume that approximately 20% of supracondylar fractures have neurologic or vascular injuries (9). An examination of the neurovascular status is important but often limited by cooperation in a scared, young child. The ulnar nerve in particular can be tricky to assess. A pearl to assess the motor portion of the ulnar nerve in young children is to palpate the first dorsal web space for setting of the interosseous muscle as the child attempts to pinch you.

The vascular status consists of two assessments: (a) is the hand pink, warm, and well perfused? and (b) is the radial pulse present? In a poorly perfused and pulseless limb, gentle flexion of the elbow to 20 to 40 degrees with gentle traction at presentation is often all that is necessary for perfusion and pulse to return. Note this is not an anatomic reduction of the fracture. If the hand remains pulseless and poorly perfused, urgent operative reduction is indicated. Arteriography or

other vascular studies are not indicated as they do not change the treatment plan of urgent reduction and may cause a delay in treatment (9).

other vascular studies are not indicated as they do not change the treatment plan of urgent reduction and may cause a delay in treatment (9).

While recent studies suggest that a delay in the treatment of supracondylar fractures is acceptable (10), do not confuse a delay in treatment with a delay in assessment. Aside from vascular concerns, fractures with excessive swelling, antecubital ecchymosis, antecubital puckering of the skin, an ipsilateral forearm fracture, sensory nerve injury, or tense forearm compartments may be at higher risk for compartment syndrome and require urgent treatment. We do not consider an isolated anterior interosseous nerve injury by itself to be an indication for urgent surgery.

Examination of the patient’s contralateral arm for assessment of carrying angle at this time may prove helpful when later assessing fracture reduction. Patients are usually consented for possible open versus closed reduction.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

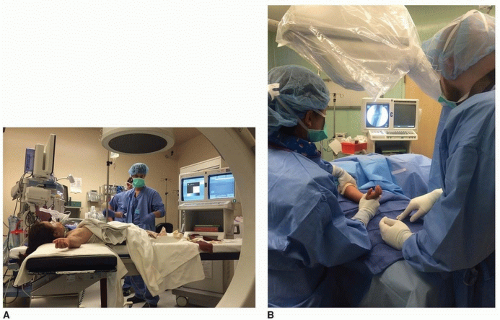

Once in the operating room, the patient receives a general anesthetic and prophylactic antibiotics. We prefer to have the fluoroscopy monitor opposite the surgeon for ease of viewing (Fig. 1-5A, B).

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, with the fractured elbow on a radiolucent arm board. Some surgeons use the wide end of the fluoroscopy unit as the table, but this will not allow rotation of the fluoroscopy unit for lateral images of the elbow in cases of instability in which rotation of the arm leads to loss of reduction. It is essential that the arm is far enough onto the arm board that the elbow can be well visualized with fluoroscopy. In very small children, this may be facilitated by having the child’s shoulder and head on the arm board (Fig. 1-6).

The patient’s entire arm from the shoulder down is then sterilized and draped to allow room for a sterile tourniquet proximally should the fracture need to be opened. First, traction is applied with the elbow flexed 20 to 30 degrees to avoid the possibility of tethering neurovascular structures over an anteriorly displaced proximal fragment. For displaced fractures, hold significant traction for 60 seconds to allow soft-tissue relaxation, with the surgeon grasping the forearm with both hands and the assistant providing countertraction in the axilla (Fig. 1-7). One often appreciates a palpable loosening of the fracture fragments at this time.

If it appears that the proximal fragment has pierced the brachialis, and this was not reduced by traction, the “milking maneuver” is performed. In this maneuver, squeeze the biceps and then forcibly “milk” the muscle past the bone in a proximal to distal direction past the proximal fragment. This will often culminate in a palpable release of the humerus posteriorly through the brachialis (Fig. 1-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree