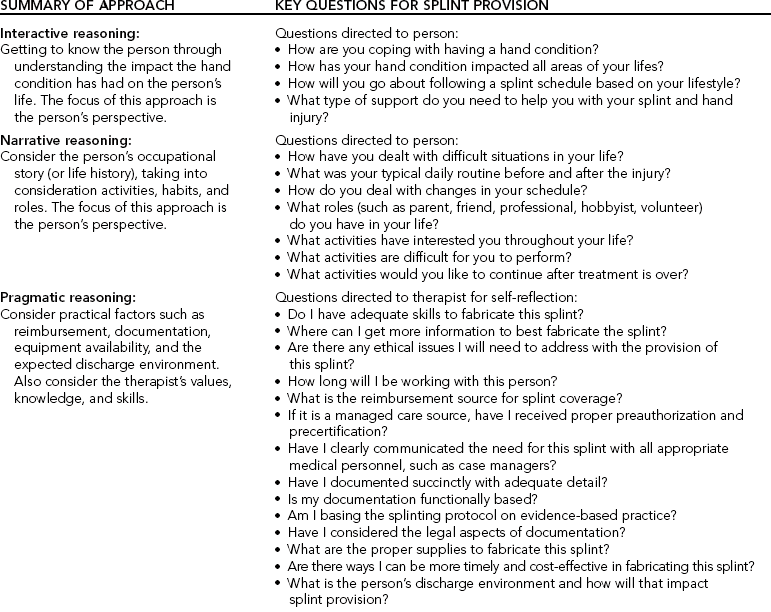

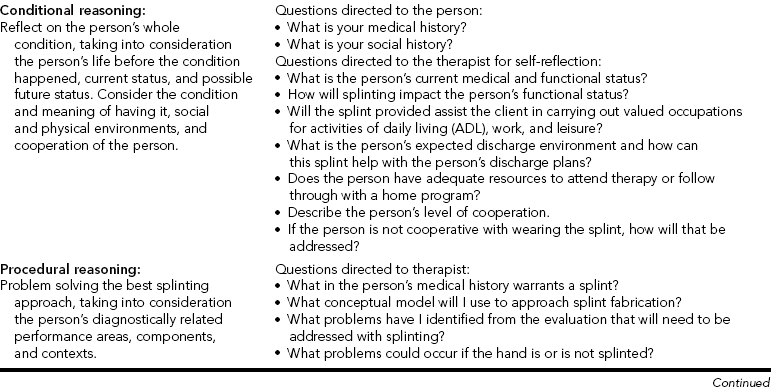

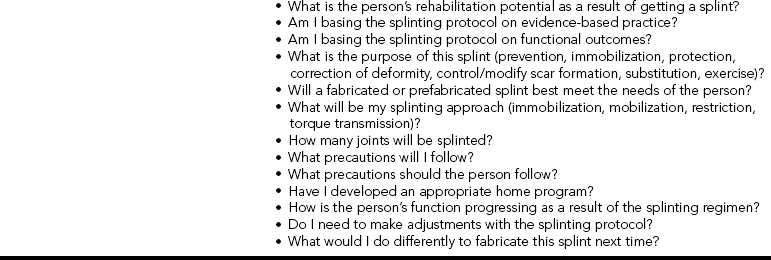

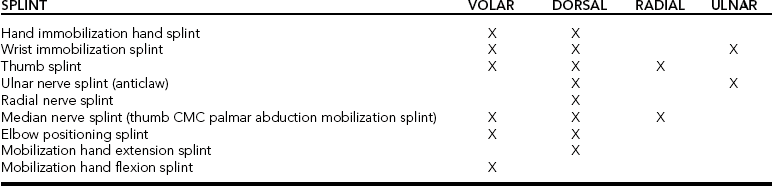

CHAPTER 6 1 Describe clinical reasoning approaches and how they apply to splinting. 2 Identify essential components of a splint referral. 3 Discuss reasons for the importance of communication with the physician about a splint referral. 4 Discuss diagnostic implications for splint provision. 5 List helpful hints regarding the hand evaluation. 6 Explain factors the therapist considers when selecting a splinting approach and design. 7 Describe what therapists problem solve during splint fabrication. 8 Describe areas that require monitoring after splint fabrication is completed. 9 Describe the reflection process of the therapist before, during, and after splint fabrication. 10 Discuss important considerations concerning a splint-wearing schedule. 11 Identify conditions that determine splint discontinuation. 12 Identify patient safety issues to consider when splinting errors occur 13 Discuss factors about splint cost and reimbursement. 14 Discuss how Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations influence splint provision in a clinic. This chapter first overviews clinical reasoning models and then addresses approaches to clinical reasoning from the moment the therapist obtains a splint referral until the person’s discharge. This chapter also presents prime questions to facilitate the clinical reasoning process the therapist undertakes during treatment planning throughout the person’s course of therapy. Clinical reasoning helps therapists deal with the complexities of clinical practice. It involves professional thinking during evaluation and treatment interventions [Neistadt 1998]. Professional thinking is the ability to distinctly and critically analyze the reasons for whatever actions therapists make and to reflect on the decisions afterward [Parham 1987]. Skilled therapists reflect throughout the entire splinting process (reflection in action), not solely after the splint is completed (reflection on action) [Schon 1987]. Clinical reasoning also entails understanding the meaning a disability, such as a hand injury, has for each person from the person’s perspective [Mattingly 1991]. Various approaches to clinical reasoning have been depicted in the literature, including interactive, narrative, pragmatic, conditional, and procedural reasoning. Although each of these approaches is distinctive, experienced therapists often shift from one type of thinking to another to critically analyze complex clinical problems [Fleming 1991] such as splinting. Interactive reasoning involves getting to know the person as a human being so as to understand the impact the hand condition has had on the person’s life [Fleming 1991]. Understanding this can help identify the proper splint to fabricate. For example, for a person who is very sensitive about his or her appearance after a hand injury the therapist may select a skin-tone splinting material that blends with the skin and attracts less attention than a white splinting material. With narrative reasoning, the therapist reflects on the person’s occupational story (or life history), taking into consideration activities, habits, and roles [Neistadt 1998]. For assessment and treatment, the therapist first takes a top-down approach [Trombly 1993] by considering the roles the person had prior to the hand condition and the meaning of occupations in the person’s life. The therapist also considers the person’s future and the impact the therapist and the person can have on it [Fleming 1991]. For example, through discussion or a formal assessment interview a therapist learns that continuation of work activities is important to a person with carpal tunnel syndrome. Therefore, the therapist fabricates a wrist immobilization splint positioned in neutral and has the person practice typing while wearing the splint. With pragmatic reasoning, the therapist considers practical factors such as reimbursement, public policy regulations, documentation, availability of equipment, and the expected discharge environment. This type of reasoning includes the pragmatic considerations of the therapist’s values, knowledge, and skills [Schell and Cervero 1993, Neistadt 1998]. For example, a therapist may need to review the literature and research evidence if he or she does not know about a particular diagnosis that requires a splint. If a therapist does not have the expertise to splint a client with a complicated injury, he or she might consider referring the person to a therapist who does have the expertise. With conditional reasoning, the therapist reflects on the person’s “whole condition” by considering the person’s life before the injury, the disease or trauma, current status, and possible future life status [Mattingly and Fleming 1994]. Reflection is multidimensional and includes the condition that requires splinting, the meaning of having the condition or dysfunction, and the social and physical environments in which the person lives [Fleming 1994]. The therapist then envisions how the person’s condition might change as a result of splint provision and therapy. Finally, the therapist realizes that success or failure of the treatment will ultimately depend on the person’s cooperation [Fleming 1991, Neistadt 1998]. Evaluation and treatment with this clinical reasoning model begin with a top-down approach, considering the meaning of having an injury in the context of a person’s life. Procedural reasoning involves finding the best splinting approach to improve functional performance, taking into consideration the person’s diagnostically related performance areas, components, and contexts [Fleming 1991, 1994; Neistadt 1998]. Much of the material in this chapter, which summarizes the treatment process from referral to discontinuation of a splint, can be used with procedural reasoning. To demonstrate clinical reasoning,Table 6-1 summarizes each approach and includes questions for the therapist to either ask the person or reflect on during splint provision and fabrication. As stated at the beginning of this discussion, each approach is explained separately. However, experienced therapists combine these approaches, moving easily from one to another [Mattingly and Fleming 1994]. The following information assists with pragmatic and procedural reasoning. The first step in the problem-solving process is consideration of the splint referral. The ideal situation is to receive the splint referral from the physician’s office early to allow ample time for preparation. In reality, however, the first time the therapist sees the referral is often when the person arrives for the appointment. In these situations the therapist makes quick clinical decisions. Aside from client demographics, Fess et al. [2005] suggest that therapists also need or should determine the following information. In some cases, the physician expects the therapist to have the clinical reasoning skills to select the appropriate splint for the specific clinical diagnosis. Sometimes a therapist receives a physician’s order for an inappropriate splint, a nontherapeutic wearing schedule, or a less than optimal material. It is the therapist’s responsibility to always scrutinize each physician referral. If the referral is inappropriate, the therapist should apply clinical reasoning skills to determine the appropriate splinting approach. The therapist makes successful independent decisions with a knowledge base about the fundamentals of splinting and with the ability to locate additional information. Then the therapist calls the physician’s office and diplomatically explains the problem with the referral and suggests a better splinting approach and rationale. See Boxes 6-1 and 6-2 for examples of complete and incomplete splinting referrals. Reflect on what you would do if you received the incomplete splint referral. The therapist identifies the person’s diagnosis after reviewing the splint order. Often, the therapist can begin the clinical reasoning process by using a categorical splinting approach according to the diagnosis. The first category involves chronic conditions, such as hemiplegia. In such a situation, a splint may prevent skin maceration or contracture. The second category involves a traumatic or acute condition that may encompass surgical or nonsurgical intervention. For example, the person may have tendinitis and require a nonsurgical splint intervention for the affected extremity. The sections that follow offer specific hints that elaborate on areas of the splinting evaluation the therapist can use with clinical reasoning. (See Chapter 5 for essential components to include in a thorough hand evaluation.) The person’s age is important for many reasons. Barring other problems, most children, adolescents, and adults can wear splints according to the respective protocol. An infant or toddler, however, can usually get out of any splint at any time or place. Extraordinary and creative methods are often necessary to keep splints on these youngsters [Armstrong 2005]. Older persons, especially those with diminished functional capacities, may require careful monitoring by the caregiver to ensure a proper fit and compliance with the wearing schedule. • What valued occupations, such as work or sports, will the person engage in while wearing the splint? • Do special considerations exist because of rules and regulations for work or sports? • In what type of environment will the person wear the splint? For example, will the splint be used in extreme temperatures? Will the splint get wet? • Will the splint impede a hand function necessary to the person’s job or home activities? • What is the person’s normal schedule and how will wearing a splint impact that schedule? When the person plans to continue in a sports program (professional, school, or community based), the therapist checks the rules and regulations governing that particular sport. Rules and regulations usually prevent athletes from wearing hard splint material during participation in the sport, unless the splint design includes exterior and interior padding. Therapists need to communicate with the coach or referee to determine appropriateness of a splint [Wright and Rettig 2005]. There has been a limited amount of research investigating compliance issues with splint provision. Only recently have experts considered compliance as it relates to persons with hand injuries [Groth and Wilder 1994, Kirwan et al. 2002]. Many considerations affect compliance with a treatment regimen, including such external factors as socioeconomic status and family support (and such internal factors as the person’s perception of the severity of the condition). Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about the condition also influence compliance [Bower 1985, Groth and Wulf 1995]. Another factor addressed in research is the psychosocial construct of locus of control, which proposes a relationship between a person’s perception of control over treatment outcomes and the likelihood the person will comply with treatment. This perception of control can be internally or externally based [Bower 1985]. For example, an internally motivated person would follow a splint schedule on his or her own motivation. An externally motivated person may need encouragement from the therapist or caregiver to follow a splint-wearing schedule. Often not discussed with compliance are organizational variables and clinic environment issues such as transportation problems, interference with daily schedule, wait time, differing therapists, and clinic location [Kirwan et al. 2002]. The therapist can positively influence the person’s compliance and motivation to wear a splint. Establishing goals together may help invest the person in the treatment. Perhaps doing an occupation-focused assessment such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) can help invest the client in wearing the splint [Law et al. 1998]. If the goals determined by the COPM are improvement of hand function, the therapist discusses how the splint will meet this goal. Furthermore, it is important for the therapist to examine her own treatment goals in relation to the client’s goals because there might be disparity between them [Kirwan et al. 2002]. Sometimes the client will have input about the splint design, which should be considered seriously by the therapist. Therapists should convey to clients that success with rehabilitation and splints involves shared responsibility. To attain the splint goal, the therapist must always clarify the person’s responsibilities in the treatment plans. In addition, the therapist should perceive the person as a whole individual with a lifestyle beyond the clinic, not just as a person with an injury. Paramount to compliance is education about the medical necessity of wearing splints, in which the therapist should consider the person’s perspectives on the ways the splints would affect his or her lifestyle. Education should be repetitive throughout the time the person wears the splint [Southam and Dunbar 1987, Groth and Wulf 1995]. When the therapist and the physician communicate clearly about the type of splint necessary, the person receives consistent information regarding the rationale for wearing the splint. Showing the way the splint works and explaining the goal of the splint enhance client compliance. Rather than labeling the person as noncompliant or uncooperative, trained personnel must make a serious attempt to help the person better cope with the injury. The therapist should be an empathetic listener as the person learns to adjust to the diagnosis and to the splint. Compliance also involves both therapist and client [Kirwan et al. 2002].Box 6-3 presents some of the many factors that may influence compliance with splint wear.Box 6-4 provides some suggested questions that may assist the therapist in eliciting pertinent information from clients about splint compliance, fit, and follow-up. Selection of an appropriate design may alleviate a person’s difficulty in adjusting to an injury and wearing a splint. Therapists should ask themselves many questions as they consider the best design. (See the questions listed in the section on procedural reasoning inTable 6-1.) In addition to splint design, material selection (e.g., soft instead of hard) may influence satisfaction with a splint [Callinan and Mathiowetz 1996]. People with rheumatoid arthritis who wear a soft prefabricated splint consider comfort and ease of use when involved in activities important factors for splint satisfaction [Stern et al. 1997]. (See the discussion of advantages and disadvantages of prefabricated soft splints in Chapter 5.) Making the splint aesthetically pleasing helps with a person’s compliance. A person is less likely to wear a splint that is messy or sloppy. This is especially true of children and adolescents, for whom personal appearance is often an important issue. The five approaches to splint design are dorsal, palmar, radial, ulnar, and circumferential. The therapist must determine the type of splint to fabricate, such as a mobilization splint or immobilization splint. Understanding the purpose of the splint clarifies these decisions. For example, when working with a person who has a radial nerve injury the therapist may choose to fabricate a dorsal torque transmission splint (wrist flexion: index-small finger MP extension/index-small finger MP flexion, wrist extension torque transmission splint, ASHT, 1992) to substitute for the loss of motor function in the wrist and MCP extensors. On the basis of clinical reasoning, the therapist may choose in addition to fabricate a palmar-based wrist extension immobilization splint once the person regains function of the MCP extensors. The wrist splint allows the person to engage in functional activities. Physicians often predetermine the splint-application approach on the basis of their training, surgical technique, and restriction/torque transmission splint with the ring and little fingers in the anticlaw position of MCP flexion (ring-small finger MP extension restriction/ring-small finger IP extension torque transmission splint, ASHT, 1992). However, a spring wire splint to hold the MCPs in flexion may be ordered if that is the physician’s preference. Sometimes the therapist may apply clinical reasoning to determine a different splint design or material than what was ordered. In that case, the therapist calls the physician. Frequently, the diagnosis mandates the approach to splint design. The diagnosis determines the number of joints the therapist must splint. The least number of joints possible should be restricted while allowing the splint to accomplish its purpose. Diagnosis also determines positioning and whether the splint should be of the mobilization or immobilization type. For example, using an early mobilization protocol for a flexor tendon repair, the therapist places the base of the splint on the dorsum of the forearm and hand to protect the tendon and to allow for rubber band traction. The wrist and MCPs should be in a flexed position (alternatively, some physicians now prefer a neutral position to block extension). These splints protect the repair and allow early tendon glide. In this example, the repaired structures and the need to begin tendon gliding guide the approach. (See Chapter 11 for more information on mobilization splint fabrication with tendon repairs.) The person’s primary task responsibilities may influence splint choice. A construction worker’s wrist has different demands placed on it than the wrist of a computer operator with the same diagnosis. Not only does the therapist choose different materials for each client but the design approach may be different. A thumb-hole volar wrist immobilization splint decreases the risk of the splint migrating up the arm during the construction worker’s activities, as it tightly conforms to the hand. The computer operator may prefer a dorsal wrist immobilization splint to allow adequate sensory feedback and unimpeded flexibility of the digits during keyboard use. (See Chapter 7 for patterns of wrist splints.) Table 6-2 outlines a variety of positioning choices for splint design. However, therapists should not view these suggestions as strict rules. For example, a skin condition may necessitate that a mobilization extension splint be volarly based rather than dorsally based.

Clinical Reasoning for Splint Fabrication

Clinical Reasoning Models

Clinical Reasoning Throughout the Treatment Process

Essentials of Splint Referral

Therapist/Physician Communication About Splint Referral

Diagnostic Implications for Splint Provision

Factors Influencing the Splint Approach

Age

Occupation

Person Motivation and Compliance

Splinting Approach and Design Considerations

Physician’s Orders

Diagnosis

Person’s Function

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Clinical Reasoning for Splint Fabrication