CHAPTER 7 Clinical history and physical examination

The position of the patient’s arm at the time of an instability episode is critical for determining the direction of instability.

The position of the patient’s arm at the time of an instability episode is critical for determining the direction of instability. The anterior apprehension test and relocation tests, when apprehension is used as the criterion for diagnosis, are very accurate.

The anterior apprehension test and relocation tests, when apprehension is used as the criterion for diagnosis, are very accurate. Any instability test (anterior or posterior) for which pain is the criterion for instability should not be taken as a diagnostic sign of instability.

Any instability test (anterior or posterior) for which pain is the criterion for instability should not be taken as a diagnostic sign of instability. Shoulder laxity testing can help in the evaluation of shoulder instability if it reproduces symptoms of instability.

Shoulder laxity testing can help in the evaluation of shoulder instability if it reproduces symptoms of instability.History

The mechanism of injury refers to the activity the individual was performing at the time of the incident, the position of the arm at the time of the injury, and the direction of force on the arm. Traumatic anterior shoulder instability typically occurs when the arm is placed in an abducted and externally rotated position with the arm in extension, such as throwing a ball or reaching behind from the front to the back seat of a car. Posterior shoulder instability typically occurs when an axial load is applied to the arm when it is in front of the body, such as an offensive lineman in football blocking with his arms outstretched in front, but it can also occur when the leading arm comes across the body into abduction, such as in the follow-through of a golf swing or when a baseball player is batting. True inferior instability, or luxatio erecta, occurs when the arm is jerked with high force from an adducted position to an abducted position in the plane of the body, resulting in the arm being stuck at approximately 90 degrees of abduction. This arm position after a dislocation distinguishes it from anterior and posterior instability, in which the arm is typically closer to the side, at approximately 20 degrees to 30 degrees of elevation.

The basic examination

Strength testing should be performed, specifically of the rotator cuff muscles. The supraspinatus can be tested with the arm abducted 90 degrees; the infraspinatus, with resisted external rotation with the arm at the side; and the subscapularis, with the lift-off test or belly-press test. Lag signs, such as the external rotation lag sign and the lift-off lag sign, are also helpful for patients with suspected rotator cuff injury after a dislocation.1 Range of motion of the shoulder, including elevation, rotations at 90 degrees of elevation, external rotation with the arm at the side, and internal rotation with the arm up the back, should be assessed. Increased external rotation with the arm at the side may be helpful for diagnosing subscapularis tendon tears, but other tests more specific for testing the subscapularis tendon (e.g., the lift-off test or belly-press test) are typically more useful in making that diagnosis.

Types of shoulder instability

Anterior shoulder instability

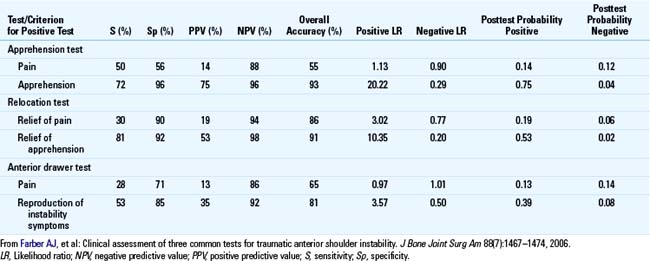

For anterior shoulder instability, the time-proven examination test is the anterior apprehension test.2 In this test, the arm is abducted, externally rotated, and extended until the patient reports apprehension that the shoulder will subluxate or dislocate (Fig. 7-1). Lo et al3 found that the position of apprehension averaged 90 degrees abduction and 83.44 degrees of external rotation. Some studies have found that the anterior apprehension test has excellent specificity (95.7% to 100%) and sensitivity (50% to 55.6%) (Table 7-1).3,4 If a patient has a positive test for apprehension then the likelihood ratio has been reported to be as high as 20.4 However, if the patient has only pain with this maneuver, then the sensitivity and specificity are significantly lower4; pain alone with this maneuver should not be interpreted as a sign of anterior instability (see Table 7-1).

A variation of the anterior apprehension test is the relocation maneuver.5 This test is performed essentially like a supine apprehension test: the patient is positioned supine, and the arm is placed in abduction, external rotation, and extension until the patient reports apprehension that the shoulder may subluxate or dislocate. When the patient reports apprehension, the examiner places a posterior force on the humeral head from the front, thereby stabilizing the humeral head (Fig. 7-2). If the patient reports that this maneuver relieves the apprehension, then the test is positive and strongly supports the diagnosis of anterior instability (likelihood ratio = 10, sensitivity = 81%, specificity = 92%).4 However, if pain is used as the criterion for a positive test instead of apprehension, Farber et al4 found that the sensitivity and specificity are much lower, and the likelihood ratio is only 31.13; they also found that the likelihood ratio of the relocation test is 3.4

FIGURE 7-2 The relocation test.

(From McFarland EG: Shoulder range of motion. In Kim TK, Park HB, El Rassi G, Gill H, Keyurapan E, editors: Examination of the shoulder: The complete guide, New York, 2006, Thieme, pp 15–87.)

A third test reported to be equally sensitive and specific for anterior instability is the surprise test.3 This test is performed exactly like a relocation test as described above except that after the humeral head has been stabilized by the examiner, the examiner then suddenly releases the stabilizing posterior force on the humeral head. This should “surprise” the patient as it recreates suddenly the forces that produce symptoms of instability. Lo et al3 reported that this test had a sensitivity of 63.89% and a specificity of 98.91%. However, they admitted that this test should be performed with caution because the patient may be caught unaware and the shoulder might subluxate or dislocate. Therefore, we do not include this test in our examination of patients with anterior instability.

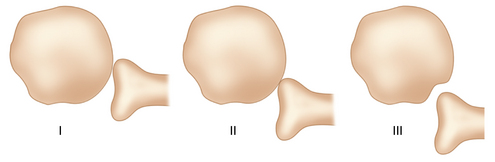

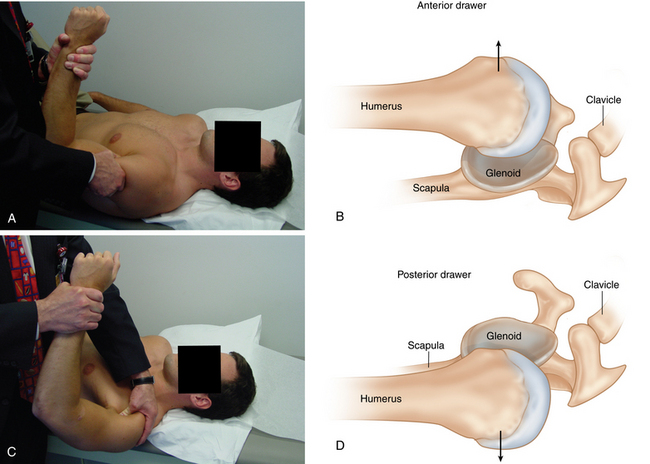

There are basically two ways to test shoulder laxity on examination. One is by performing the anterior and posterior drawer tests (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4) as described by Gerber et al.6 These tests are performed by elevating the arm to 70 to 80 degrees and then stabilizing the scapula by creating an axial force up the humerus into the glenoid. The hands are then used to subluxate the shoulder anteriorly and posteriorly to see if the humeral head can be subluxated over the glenoid rim (see Fig. 7-2). The second way to measure shoulder laxity is with the load-and-shift test,7 which is typically performed with the patient sitting. This test is performed by stabilizing the scapula and shoulder by placing one hand on the top of the shoulder and placing the second hand on the arm. The arm is held in a position of 20 degrees of abduction, 20 degrees of flexion, and in neutral, and the clinician exerts an anterior and posterior force to translate the humeral head over the glenoid rim.

FIGURE 7-3 Laxity testing using the anterior (A, B) and posterior (C, D) drawer signs.

(Parts A and C from McFarland EG: Instability and laxity. In Kim TK, Park HB, El Rassi G, Gill H, Keyurapan E, editors: Examination of the shoulder: The complete guide, New York, 2006, Thieme, pp 162–212.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree