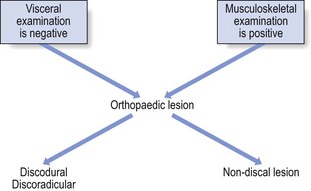

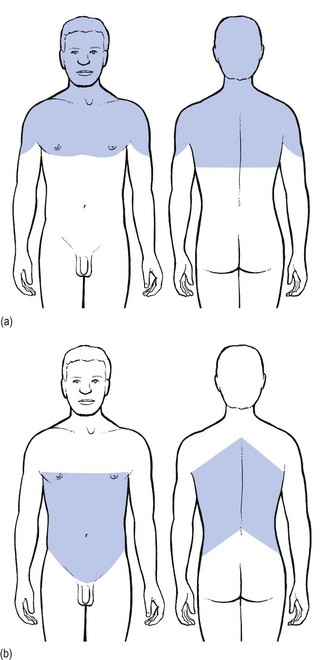

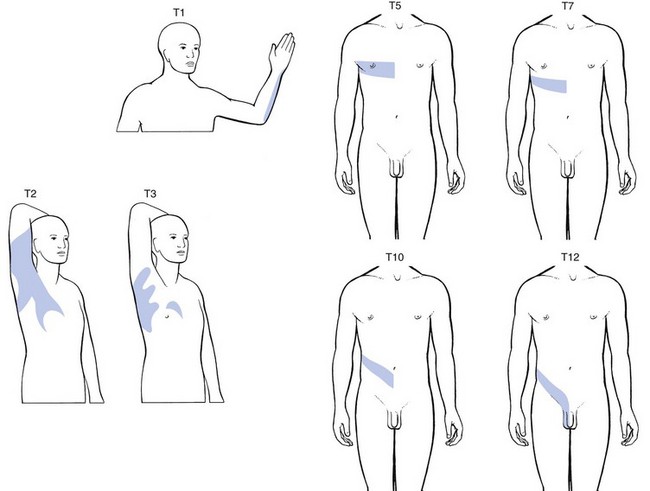

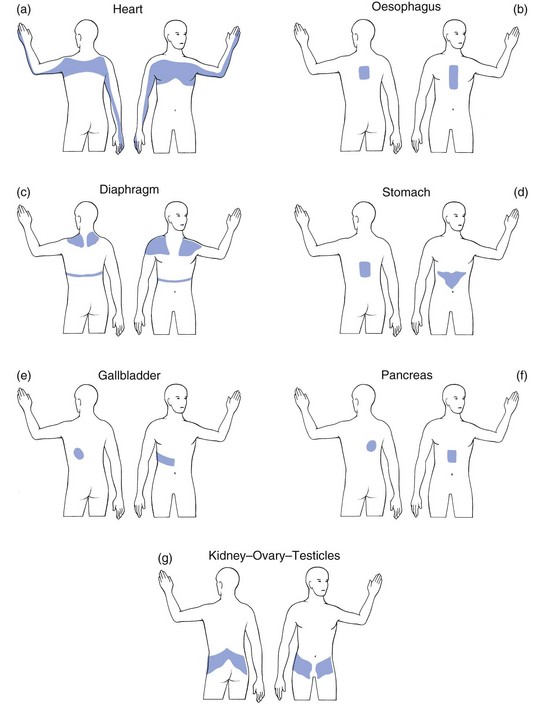

25 The best method of differentiating is to work in two complementary ways: exclusion of any visceral disorder through a thorough internal check-up, together with positive confirmation of a provisional orthopaedic diagnosis (Fig. 25.1). This routine will also safeguard against unnecessary technical investigations and delays in diagnosis and treatment.1–3 Discodural and discoradicular interactions are well-known causes of cervical and lumbar pain. In a discodural lesion, a shifted component of the disc impinges on the dura and causes pain that has multisegmental characteristics (crossing the midline and occupying several dermatomes). Discodural conflicts are characterized by two sets of symptoms and signs: articular and dural (see Ch. 33). • The articular signs are subtle: a discodural interaction at the cervical or lumbar level usually presents with a clear partial articular pattern: some movements hurt or are limited and others do not, always in an asymmetrical way. This is not so in the thoracic spine. Because of the rigidity of the thorax, such an obvious pattern is seldom found. Very often, only one of the six passive movements, usually a rotation, is positive and then only slightly so. Therefore diagnosis in the thoracic spine is more tentative and may have to be based on smaller, subtler abnormalities. • Neurological deficit is seldom encountered in a thoracic disc lesion: whereas some degree of neurological deficit is a common finding in cervical or lumbar posterolateral disc lesions, muscular weakness is rarely detectable in thoracic discoradicular lesions. Also, disturbance of sensation is very rare. This absence of neurological signs is probably the outcome of the location of the nerve root in the intervertebral foramen, where it lies mainly behind the lower aspect of the vertebral body and less behind the disc (see online chapter Applied anatomy of the thorax and abdomen). • There is no tendency to spontaneous recovery: in the lumbar and cervical spines there is usually a spontaneous cure for root pain, which seldom lasts longer than 4 months at the cervical level and 12 months at the lumbar level. At the thoracic level, no such tendency exists and constant root pain can persist for many years. • Protrusions can usually be reduced: although thoracic disc lesions are more difficult to diagnose, they are easily and effectively cured. Protrusions – no matter how long they have been present, or whether they are posterocentral or posterolateral, or soft or hard – can usually be reduced by 1–3 sessions of manipulations. Unlike at the lumbar or cervical levels, time is not a criterion for reducibility. Hence a disc displacement may well prove reducible after constant root pain, even of several years’ standing. Traction is seldom required because the protrusions are usually of the annular type. Pain originating from the dura mater is referred in a multisegmental way: it crosses the midline and may cover several consecutive dermatomes (see p. 18). A possible explanation for this phenomenon may lie in its multisegmental origin, which is reflected in the considerable overlap between the fibres of the consecutive sinuvertebral nerves innervating its anterior aspect.4 Recent research has demonstrated that dural pain may spread over eight segments with considerable overlap between adjacent and contralateral dura mater.5 This may be an explanation for the fact that lower cervical discodural conflicts may produce pain that spreads into the upper thoracic level (Fig. 25.2a) or that lumbar dural pain causes pain in the lower thoracic region (Fig. 25.2b). Some cervical disc lesions may cause pain in the thoracic region. Low cervical discodural interactions very often result in unilateral interscapular pain, usually felt above T6 and spread over several dermatomes. The pain is also often referred to the sternum and the precordial region. Exceptionally, the pain may be felt only in the anterior chest, so misleading almost all clinicians. It is important to remember that extrasegmentally referred pain of cervical origin never spreads into the upper limb (see p. 18). A posterolateral disc protrusion compressing the C5, C6, C7 or C8 nerve root gives rise to unilateral root pain characterized mainly by a sharp pain down the upper limb. There may also be some degree of scapular pain, especially in C7 lesions, but this is usually not very severe (see p. 156). It is important to note that extrasegmental pain from a posterocentral thoracic disc protrusion usually remains in the trunk itself, where it can spread anteriorly and/or posteriorly over several segments (see Fig. 25.2b). It seldom spreads into the neck or into the buttocks. The pain is usually unilateral and spreads over several segments. Exceptionally it is felt centrally at the spine, radiating bilaterally towards the sides. A posterolateral impingement on the two upper thoracic roots produces pain felt in the arm (Fig. 25.3). If the T1 nerve root is involved, pain may be referred to the ulnar side of the forearm, whereas a T2 nerve root compression gives rise to pain felt over the inner aspect of the arm from the elbow to the axilla, at the anterior aspect of the upper thorax around the clavicle and at the posterior upper thorax around the scapular spine. Clinically the upper two thoracic segments belong to the cervical spine and are thus most easily examined with the cervical segments. If the 3rd–12th root is compressed, pain spreads unilaterally as a band around the thorax, sometimes reaching anteriorly as far as the sternum (see Fig. 25.3). The following landmarks may be helpful in determining which root is involved: • If pain is felt around the nipple, the T5 nerve root is at fault. • Because the epigastrium belongs to the T7 and T8 segments, pain present here arises from structures of the same origin. • Pain at the umbilicus and in the iliac fossa may point to a lesion of the T9, T10 and T11 nerve roots. • If the T11 or T12 thoracic root is compressed, pain may be referred to the groin or even further down to the testicle. • Traumatic fracture of a vertebral body: severe central pain is to be expected for about 2–6 weeks. For the first week there is often girdle pain. Thereafter it gradually disappears. If uncomplicated, spontaneous cure is to be expected within 12 weeks. • Vertebral tumours: all types of bony tumour of the vertebrae, primary or metastatic, as well as infections, initially provoke local pain in the centre of the back. • Contusion or fracture of a rib: the patient can point exactly to the tender spot. The same is the case in malignant invasion. • Disorders of the sternum: traumatic disorders and tumours of the sternum may also give rise to local sternal pain. • Manubriosternal and sternoclavicular joints: as these are superficially located, the pain is felt locally. • Costochondral and chondrosternal joints (Tietze’s syndrome and costochondritis): the patient is able to indicate the site of the lesion accurately. • Intervertebral facet joints: these give rise to unilateral paravertebral pain, felt deeply and locally, but not going further lateral than the medial edge of the scapula. If several joints are affected at the same time, as may be the case in ankylosing spondylitis, the pain spreads more in a craniocaudal direction than mediolaterally; the opposite is true for a disc protrusion. • Costovertebral and costotransverse joints: the pain is felt unilaterally between the vertebral column and the scapula. • Anterior longitudinal ligament: when this ligament is affected, pain is usually located anteriorly behind the sternum. • Posterior longitudinal ligament: involvement of this ligament causes pain in the back, felt centrally between the scapulae. • Disorders of the costocoracoid fascia or the trapezoid and conoid ligaments (see online chapter Disorders of the inert structures): the pain is usually felt in the infraclavicular fossa. Pain arising from disorders of the heart can be referred to dermatomes C8–T4 because the heart is derived largely from these segments. Therefore pain can radiate towards the tip of the shoulder, to the anterior chest and to the corresponding region of the back. It may also be referred towards the ulnar side of both upper limbs, though referral to the left side is more common (Fig. 25.4a). Pain from the pericardium always arises from the parietal surface because this is the only part which has a sensory innervation. Pleuritic pain is caused by an inflammation of the parietal pleura (pleurisy). Though the visceral pleura does not contain any nociceptors, the parietal pleura is innervated by somatic nerves that sense pain when the parietal pleura is inflamed. Parietal pleurae of the outer rib cage and lateral aspect of each hemidiaphragm are innervated by intercostal nerves. Pain is localized to the cutaneous distribution of those nerves. The phrenic nerve supplies innervations to the central part of each hemidiaphragm which is a C4 structure, with pain reference to the trapezius area.6 Disorders of the oesophagus (T4–T6) usually give rise to pain felt at any part of the sternum, often radiating between the scapulae into the back (Fig. 25.4b). The central part of the diaphragm is mainly derived from the third, fourth and sometimes, although rarely, the fifth cervical segments. Pain from irritation of the central part of the diaphragm is felt at the tip of the shoulders and the base of the neck. Pain from the peripheral part is felt more locally in the lower thorax and in the upper abdomen at the costal margin (Fig. 25.4c). Pain from stomach and duodenum (T6–T10) is most commonly felt in the epigastrium and upper abdomen, sometimes substernally and exceptionally in the lower thoracic part of the back (Fig. 25.4d). The liver is derived from the right side of T7–T9. The gallbladder and bile ducts are of right T6–T10 origin. Pain is felt in the right hypochondrium and may radiate towards the inferior angle of the right scapula (T7–T9) (Fig. 25.4e). Patients suffering from a pancreatic disorder complain of upper abdominal pain often referred to the back at T8 (Fig. 25.4f). Disorders of kidney and ureters (T10–L1) give rise to pain felt posteriorly in the side, at and just below the lower ribs, and at the anterolateral aspect of the abdomen. The pain often radiates towards the testicles or the labia (Fig. 25.4g).7

Clinical examination of the thoracic spine

Introduction

Principal differences between the thoracic and the lumbar and cervical spines

Visceral versus musculoskeletal pain

Discal lesions

Referred pain

Pain referred from musculoskeletal structures

Dura mater and nerve roots

Cervical disc lesions

Cervical discodural interactions

Cervical discoradicular interactions

Thoracic disc lesions

Thoracic discodural interactions

Thoracic discoradicular interactions

Bones

Joints and ligaments

Pain referred from visceral structures

The heart

The lungs

The parietal pleura

The oesophagus

The diaphragm

The stomach and duodenum

The liver, gallbladder and bile ducts

The pancreas

The kidneys and ureters

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access